Between 1894 and 1952 the United States suffered a series of epidemic outbreaks of poliomyelitis. The worst of these, in 1916, claimed six thousand lives. For another forty years polio would remain a substantial threat to public health. The development of a vaccine changed all that: by 1994 the disease had been eradicated not only in the United States but in the whole Western Hemisphere.

Polio has been around for millennia as a contagious viral disease. Before the twentieth century it was an endemic infection of early childhood, causing fever, headaches, and nausea, no worse. In only a tiny minority of cases did it assume full-blown form and attack the nervous system, leading to paralysis or even death.

The mutation of polio into a serious disease can be blamed on improved standards of hygiene. The polio virus is passed on via human feces (the virus breeds in the small intestine). A regime of hand-washing, regular baths, and clean underwear cuts down transmission. The catch is that clean habits rob communities of resistance to the virus; and when nonresistant older children and adults contract the disease, it tends to take an extreme form. Thus the very measures that subdued diseases like cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, and diphtheria made poliomyelitis a threat to life.

The paradox that while strict hygiene lessens the risk to individuals, it weakens resistance and turns the disease lethal, was not widely grasped in the heyday of polio. In afflicted communities, eruptions of polio would trigger parallel and no less morbid eruptions of anxiety, despair, and misdirected rage.

The psychopathology of populations under attack by diseases whose transmission is ill understood was explored by Daniel Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year, which pretends to be the journal of a survivor of the bubonic plague that decimated London in 1665. Defoe records all the moves typical of plague communities: superstitious attention to signs and symptoms; vulnerability to rumor; the stigmatization and isolation (quarantining) of suspect families and groups; the scapegoating of the poor and the homeless; the extermination of whole classes of suddenly abhorred animals (dogs, cats, pigs); the fragmenting of the city into healthy and sick zones, with aggressive policing of boundaries; flight from the diseased center, never mind that contagion might thereby be spread far and wide; and rampant mistrust of all by all, amounting to a general collapse of social bonds.

Albert Camus knew Defoe’s Journal: in his novel The Plague (La Peste), written during the war years, he quotes from it and generally imitates the matter-of-fact tone of Defoe’s narrator toward the catastrophe unfolding around him. Nominally about an outbreak of bubonic plague in an Algerian city, The Plague also invites a reading as being about what the French called “the brown plague” of the German occupation, and more generally as about the ease with which a community can be infected by a bacillus-like ideology. It concludes with a sober warning:

The plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good;…it can bide its time for decades, slumbering in furniture and linen;…it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs, old papers;…perhaps the day will come when, for the affliction and instruction of humankind, the plague will rouse up its rats again and send them out to die in a happy city.

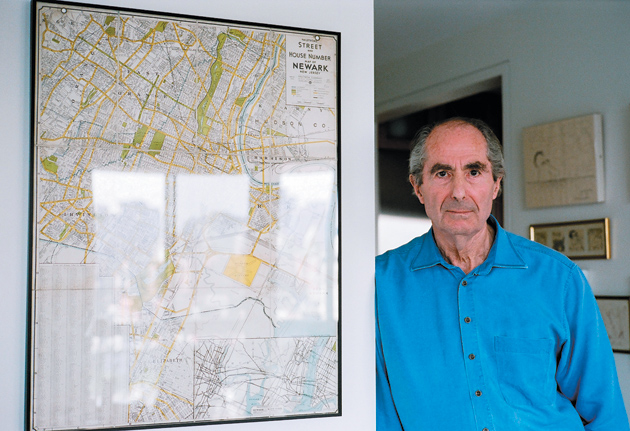

In a 2008 interview, Philip Roth mentioned that he had been rereading The Plague. Now he has published Nemesis, set in Newark in the polio summer of 1944 (19,000 cases nationwide), thereby placing himself in a line of writers who have used the plague condition to explore the resolve of human beings and the durability of their institutions under attack by an invisible, inscrutable, and deadly force. In this respect—as Defoe, Camus, and Roth are aware—the plague condition is simply a heightened state of the condition of being mortal.

Eugene “Bucky” Cantor is a physical education instructor at a public school. Because of poor eyesight he has been exempted from the draft. He is ashamed of his good fortune and tries to pay for it by giving the children in his charge every care and attention. In return the children adore him, particularly the boys.

Bucky is twenty-three years old, levelheaded, dutiful, and scrupulously honest. Though not an intellectual, he thinks about things. He is a Jew, but an indifferent practitioner of his religion.

Polio breaks out in Newark and is soon sweeping through the Jewish section. Amid the general panic Bucky stays calm. Convinced that what children need in time of crisis is stability, he organizes a sports program for the boys and continues to run it against the doubts of the community, even when some of the boys begin to sicken and die. To set an example of human solidarity in the face of the plague, he openly shakes hands with the local simpleton, who is shunned by the boys as a carrier. (“Smell him!… He has shit all over him!… He’s the one who’s carrying the polio!”) In private Bucky rails against the “lunatic cruelty” of a God who kills innocent children.

Bucky has a girlfriend, Marcia, also a teacher, who is away helping run a summer camp in the mountains of Pennsylvania. Marcia puts pressure on Bucky to flee the infected city and join her in her haven. He resists. On the home front as much as in Normandy or the Pacific, he feels, these are extraordinary times calling for extraordinary sacrifice. Nonetheless, one day his principles inexplicably collapse. Yes, he says, he will come to her; he will abandon his boys and save himself. “How could he have done what he’d just done?” he asks himself the moment he hangs up. He has no answer.

Advertisement

Nemesis is an artfully constructed, suspenseful novel with a cunning twist toward the end. Generally, a reviewer will try not to spoil the impact of a book by giving away its proper secrets. But I see no way of exploring Nemesis further without breaking this rule. The secret is that Bucky Cantor carries the polio virus. More specifically, he is that statistically rare creature, a healthy infected carrier. The boys in Bucky’s care who sickened and died may well have been infected by him; the man whose hand he shook may be doomed. Furthermore, when Bucky flees the plague-ridden city he will be bearing the plague into an idyllic retreat where a party of innocents believe they are safe.

The rest of the tale of Bucky is quickly told. Shortly after his arrival at the camp, polio erupts there. Bucky has himself tested and the terrible truth emerges. He himself then succumbs. After treatment he is discharged from the hospital a cripple. Marcia still wants to marry him but he refuses, preferring bitter isolation. Marcia speaks:

“You’re always holding yourself accountable when you’re not. Either it’s terrible God who is accountable, or it’s terrible Bucky Cantor who is accountable, when in fact, accountability belongs to neither. Your attitude toward God—it’s juvenile, it’s just plain silly.”

“Look [Bucky replies], your God is not to my liking, so don’t bring Him into the picture. He’s too mean for me. He spends too much time killing children.”

“And that is nonsense too! Just because you got polio doesn’t give you the right to say ridiculous things. You have no idea what God is! No one does or can!

God is not accountable because God is above accountability, above mere human reckoning. Marcia echoes the God of the Book of Job, and the scorn expressed there for the puniness of the human intellect. (“Canst thou by searching find out God?”) But Roth’s novel evokes a Greek context more explicitly than it does a biblical one. The title Nemesis frames the interrogation of cosmic justice in Greek terms; and the plot pivots on the same dramatic irony as in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex: a leader in the fight against the plague is unbeknown to himself a bringer of the plague.

What exactly is Nemesis (or nemesis, the abstract noun)? Nemesis (the noun) exactly translates the Latin word indignatio, from which we get English “indignation”; and Indignation happens to be the title of a book Roth published in 2008 (the plot thickens), a book that, together with Everyman (2006), The Humbling (2009), and Nemesis, belongs to a subgroup of his oeuvre that Roth calls “Nemeses: Short Novels.”

Indignatio and nemesis are words of complex meaning: they refer to both unbefitting (unjust) actions and feelings of (just) anger at such actions. Behind nemesis (via the verb nemo, to distribute) lies the idea of fortune, good or bad, and how fortune is dealt out in the universe. Nemesis (the goddess, the cosmic force) sees to it that those who prosper beyond what is fitting are humbled. Thus Oedipus, conqueror of the Sphinx and great king, leaves Thebes a blind beggar. Thus Bucky Cantor, admired athlete—the most lyrical pages of Nemesis celebrate his prowess as a javelin thrower—ends up a cripple behind a desk in the post office.

Since he wittingly did no wrong, Oedipus is not a criminal. Nevertheless, his actions—parricide, incest—pollute him and pollute whatever he touches. He must leave the city. “No man but I can bear my evil doom,” he says (David Grene’s translation). Bucky has likewise committed no crime. Yet even more literally than Oedipus, he is polluted. He too accepts his guilt and, in his own manner, takes the lonely road of exile.

At the core of the Oedipus fable, and of the archaic Greek worldview enshrined in it, lies a question foreign to the modern, post-tragic imagination. How does the logic of justice work when vast universal forces intersect the trajectories of individual human lives? In particular, what is to be learned from the fate of a man who unwittingly carried out the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother, a man who did not see until he was blind?

Advertisement

To respond that for one man to unwittingly (“by accident”) kill his own father and then unwittingly (“by chance”) marry his own mother is so statistically rare a sequence of events—even rarer than bearing the plague while seeming healthy—that it can hold no general lesson, or, to put it another way, that the laws of the universe are probabilistic in nature, not to be disconfirmed by a single aberrant individual case—to respond in this way would to Sophocles seem like evading the question. Such a man lived: his name was Oedipus. He experienced such a fate. How should his fate be understood?

Nemesis is not openly named by Sophocles, for which he doubtless had his reasons. Nevertheless, nemesis pervades Greek tragedy as a feared force presiding over human affairs, a force that redistributes fortune downward toward the middle or middling, and is in that sense mean, mean-minded: unkind, ungenerous, unrelenting. At one time all of Thebes envied Oedipus, says the chorus at the end of the play, yet look at him now! Greek tradition is full of cautionary tales of mortals who provoke the envy (nemesis) of the gods by being too beautiful or too happy or too fortunate, and are then made to suffer for it. The chorus, as an embodiment of received Theban opinion, is all too ready to package the story of Oedipus along these lines.

There is a Greek-chorus way of reading the story of Bucky Cantor too. He was happy and healthy, he had a fulfilling job, he was in love with a beautiful girl, he had a 4-F exemption; when the plague struck the city (the plague of polio, the plague of paranoia) he was not cowed but battled against it; whereupon Nemesis took aim at him; and look at him now! Moral: Don’t stand out from the crowd.

The story of Newark’s polio summer comes to us, for the first twenty pages or so, via someone (male) from Newark’s Jewish section who takes care not to name himself, uses “we” at every turn instead of “I,” and is generally so unobtrusive that the question of who he is barely rises. After twenty pages, as we move into the story of Bucky, even the most minimal traces of an identifiable storyteller vanish. So familiar does the narrating voice turn out to be with what goes on in Bucky’s mind that we might guess it is simply Bucky’s own I-voice transposed into the third person; or if not that then the voice of some impersonal, bodiless narrator, neither inventor of the story nor participant in it. Though this being now and again lets fall a mot juste—“He had begun to cry, awkwardly, inexpertly, the way men cry who ordinarily like to think of themselves as a match for anything” (my italics)—he is certainly not the Philip Roth we know, either in style or in expressive power or in intellect.

Only fleetingly is our assumption disturbed that this is Bucky’s story—both the story of Bucky and a story that Bucky in some sense authorizes. “Mr. Cantor” seems an oddly formal name for oneself, yet that is how Bucky is more often than not referred to. After a hundred pages, in among a list of boys who came down with polio, there occurs the puzzling phrase “me, Arnie Mesnikoff.” But having surfaced for a moment, “me, Arnie” sinks away again, not to resurface until forty pages from the end, when he comes forward to announce himself as no less than the author—more specifically the as-told-to author—of the story we have been reading. In 1971, he explains, he encountered his ex-teacher Bucky Cantor in the street, greeted him, and eventually became a confidant close enough to now relate his history. (“Now” is given no date, but we infer that Bucky is deceased.)

Thus the narratorial device that we have assumed—the mask or voice with no mind of its own and no stake in the story—is thrust aside and a stranger, Arnie Mesnikoff, reveals himself to have been present all the time as a full-blooded interpreter between Bucky Cantor and ourselves. Nemesis thus continues Roth’s long-running practice of complicating the line of transmission along which the story reaches the reader and putting in question the mediator’s angle on it. The experience of reading The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography (1988) or Operation Shylock (1993), to name only two examples, is dominated by uncertainty about how far the narrator is to be believed. Indeed, Operation Shylock is built on the Cretan-liar paradox of a narrator who asserts that he is lying.

In Roth’s recent fiction the question of how the story reaches us is as prominent as ever. Though neither Everyman nor Indignation is in any sense mystical, both novels turn out to be narrated from, so to speak, beyond the grave. Indignation even includes meditations, reminiscent of the Beckett of The Unnamable and How It Is, on post-mortem existence and what it is like to have to spend eternity going over and over the story of one’s life on earth.

The revelation that Bucky has been refracted through the mind of another fictional character, someone about whose life we never learn much beyond that as a boy he was quiet and sensitive, that in 1944 he was struck down by polio, and that he later became an architect specializing in home modifications for the disabled, requires that we reconsider the whole story we have been reading. If it seems unlikely that the prickly Bucky would have confided to the younger man the details of his lovemaking with Marcia, then is Arnie making up that part? And if he is, may there not be other parts of Bucky’s story that he has left out, misinterpreted, or simply not been competent to represent?

(Arnie puts it on record that the young Marcia had “tiny breasts, affixed high on her chest, and nipples that were soft, pale, and unprotuberant.” What does a word like “affixed” say about Arnie’s sense of a woman’s body, or, more to the point, about Arnie’s sense of Bucky’s sense?)

Arnie’s attitude toward the post-polio Bucky is at the very least ambivalent. To an extent he can respect Bucky’s single-minded devotion to his self-chosen task of punishing himself. But in the main he finds people like Bucky wrongheaded and excessive. Our lives are subject to chance, he believes; when Bucky rails against God, he is in fact railing against chance, which is stupid. A polio epidemic is “pointless, contingent, preposterous, and tragic”; there is no “deeper cause” behind it. In attributing hostile intent to a natural event, Bucky has exhibited “nothing more than stupid hubris, not the hubris of will or desire but the hubris of fantastical, childish religious interpretation.” If he, Arnie, has made his peace with what befell him, then Bucky can do the same. The calamity of the summer of 1944 “didn’t have to be a lifelong personal tragedy too.”

Arnie’s life of Bucky culminates in a page-long summation in which Bucky’s philosophical position is pretty much trashed. Bucky was a humorless soul with no saving sense of irony, a man with an overblown sense of duty and not enough intellect. By brooding too long on the harm he had caused, he turned a quirk of chance into “a great crime of his own.” Temperamentally unable to come to terms with unmerited human suffering, he took on the guilt for that suffering and used it to punish himself endlessly.

Though he sometimes wavers, this is in substance Arnie’s verdict on Bucky. Sympathetic to the man, he is deeply unsympathetic, even uncomprehending, toward his worldview. A modern soul, Arnie has found ways of navigating a world beyond good and evil; Bucky, he feels, should have done the same.

Back in the 1940s, Bucky looked at what polio was doing to Newark (and what war was doing to the world), concluded that whatever force was running the show could only be malign, and vowed to resist that force, if only by refusing to bend his knee to it. It is this resistance on Bucky’s part that Arnie singles out as “stupid hubris.” On the same page that he writes of hubris he uses the word “tragic” as if it belonged in the same semantic field as “pointless,” “contingent,” and “preposterous.”

Since Arnie does not go ahead to reflect on ancient (elevated) versus modern (debased) conceptions of the tragic—from what we know of him we might suspect that he would not see the point—we may guess that it is the ironical author himself who is dropping these telling Greek terms into Arnie’s discourse, and not without purpose. That purpose, one might guess further, might be to arm the hapless Bucky against his spokesman, to suggest that there may be a way of reading Bucky’s resistance other than the dismissive way Arnie offers. Such a reading—briefly, so as not to build upon the lightest of authorial hints a mountain of interpretation—might commence with the emending of Arnie’s characterization of polio epidemics (and by extension other destructive acts of God) as “pointless, contingent, preposterous, and tragic” to “pointless, contingent, preposterous, yet nevertheless tragic.”

God may indeed be incomprehensible, as Marcia says. Nonetheless, someone who tries to grasp God’s mysterious designs at least takes humanity, and the reach of human understanding, seriously; whereas someone who treats the divine mystery as just another name for chance does not. What Arnie is unwilling to see—or at least unwilling to respect—is first the force of Bucky’s Why? (“this maniac of the why,” he calls him) and then the nature of Bucky’s No!, which, pigheaded, self-defeating, and absurd though it may be, nevertheless keeps an ideal of human dignity alive in the face of fate, Nemesis, the gods, God.

The unkindest—and meanest—cut of all comes when Arnie disparages Bucky’s transgression itself, the wellspring of all his woe. Just as God cannot be a great criminal masterminding the woes of humankind (because God is just another name for chance), so carrying the polio virus cannot be a great crime, just a matter of ill luck. Ill luck does not call for remorse on a grand, heroic scale: best to pick yourself up and get on with your life. In wanting to be regarded as a great criminal, Bucky merely reveals himself as a belated imitator of the great-criminal pretenders of the nineteenth century, desperate for attention and ready to do anything, even commit the vilest of crimes, to get it (Dostoevsky dissected the great-criminal type in the person of Stavrogin in The Possessed).

In Nemesis we witness plenty of deplorable behavior on the part of a plague- and panic-stricken populace, not excluding ethnic scapegoating. The Newark of Nemesis turns out to be a no less fertile breeding ground for anti-Semitism than the cities of Roth’s dystopian fantasy The Plot Against America (2004), set in the same time period. But in his narrative of the plague year of 1944 Roth’s concern is less with how communities behave in times of crisis than with questions of fate and freedom.

It seems to be a rule of tragedy that only in retrospect can you see the logic that led to your fall. Only after Nemesis has struck can you work out what provoked her. In each of the four Nemeses novels there occurs a slip or fall from which it turns out the hero cannot recover. Nemesis has done her work; life will never be the same again. In The Humbling a famous actor inexplicably loses his power to hold an audience; this loss is followed by a failure of male sexual power. In Everyman the protagonist, looking forward to a comfortable retirement, feels his life horizons shrink to nothing as without warning he falls into all-consuming dread. In Indignation the young hero’s modest-seeming resolution to have sexual intercourse at least once before he dies leads by an inscrutable logic to his expulsion from college and his death in Korea, still, in a Clintonian sense, a virgin. His father’s prophecy is fulfilled: “The tiniest misstep can have tragic consequences.”

In Nemesis the action pivots on what seems a tiny misstep that in retrospect turns out to be a fatal fall. It occurs at the instant when Bucky gives in to his girlfriend’s pleas and agrees to quit Newark. Intuition warns him that he is betraying himself, acting against his higher interests. He is on some kind of moral brink; yet he does nothing to save himself from falling.

Bucky thus provides a textbook example of weakness or failure of the will, which as a moral/psychological phenomenon has attracted the attention of philosophers since Socrates. How is it possible that we can knowingly act against our own interests? Are we indeed, as we like to think of ourselves, rational agents; or are the decisions we arrive at dictated by more primitive forces, on whose behalf reason merely provides rationalizations? To Bucky the instant when he made his decision—the instant when he fell—remains opaque. The Bucky with whom Arnie does not sympathize is haunted by a suspicion that when he said “Yes, I will flee the city,” the voice that spoke was not that of his daytime self but of some Other within him.

Compared with works of such high ambition as Sabbath’s Theater (1995) or American Pastoral (1997), the four Nemeses novels are lesser additions to the Roth canon. Nemesis itself is not really large enough in conception—in the inherent capacities of the characters it deploys, in the action it gives them to play out—to do more than scratch the surface of the great questions it raises. Despite its length (280 pages) it has the feel of a novella.

There is a further sense in which the four Nemeses novels are minor. Their overall mood is subdued, regret-filled, melancholy: they are composed, as it were, in a minor key. One can read them with admiration for their craft, their intelligence, their seriousness; but nowhere does one feel that the creative flame is burning at white heat, or the author being stretched by his material.

If the intensity of the Roth of old, the “major” Roth, has died down, has anything new come in its place? Toward the end of his life on earth, “he,” the protagonist of Everyman, visits the graveyard where his parents lie buried and strikes up a conversation with a gravedigger, a man who takes a solid, professional pride in his work. From him “he” elicits a full, clear, and concise account of how a good grave is dug. (Among the subsidiary pleasures Roth provides are the expert little how-to essays embedded in the novels: how to make a good glove, how to dress a butcher’s display window.) This is the man, “he” reflects, who when the time comes will dig his grave, see to it that his coffin is well seated, and, once the mourners have dispersed, fill in the earth over him. He bids farewell to the gravedigger—his gravedigger—in a curiously lightened mood: “I want to thank you…. You couldn’t have made things more concrete. It’s a good education for an older person.”

This modest but beautifully composed little ten-page episode does indeed provide a good education, and not just for older persons: how to dig a grave, how to write, how to face death, all in one.

This Issue

October 28, 2010