Life never bribed him to look at anything but the soul, Henry James said of Emerson, and one could say the same of James Baldwin, with a similar suggestion that the price for his purity was blindness about some other things in life. Baldwin possessed to an extraordinary degree what James called Emerson’s “special capacity for moral experience.” He, too, is persuasive in his antimaterialism. Baldwin, like Emerson, renounced the pulpit—he had been a fiery boy preacher in Harlem—and readers have found in the writings of each the atmosphere of church.

It’s not that Emerson and Baldwin have much in common as writers. Harlem was not Concord. Except for his visits to England, Emerson stayed put for fifty years and Baldwin spent his adult life in search of a home. He left Harlem for Greenwich Village in the early 1940s, left Greenwich Village for Paris in 1948, and spent much time in Paris, Turkey, and the South of France between the 1950s and the 1980s. Yet Baldwin and Emerson both can speak directly to another person’s soul, as James would have it, in a way that “seems to go back to the roots of our feelings, to where conduct and manhood begin.”

Baldwin, as much as Emerson, is a legatee of certain Nonconformist beliefs—that every person is a carrier of the divine spark, for instance, an idea that became secular in the time of the American Revolution through arguments regarding the authority of the individual in a political democracy. If this is one of the founding traditions of American radicalism, then it links the abolitionism of Emerson’s day with the civil rights movement of Baldwin’s. Many intellectuals in the 1960s were aware that the freedom movement was a taking up of what had been left brutally undone since Emancipation. The antislavery cause of a century earlier offered to civil rights activists examples of individual conscience as judge of unjust government and its laws. When the protests of the late 1950s and 1960s that Baldwin wrote about brought the Paris expatriate back to the US, the connection between racial justice and democracy in America was once again at the center of the nation’s politics, asking every citizen to realize that his or her liberty was not freedom so long as other Americans were being denied their rights.

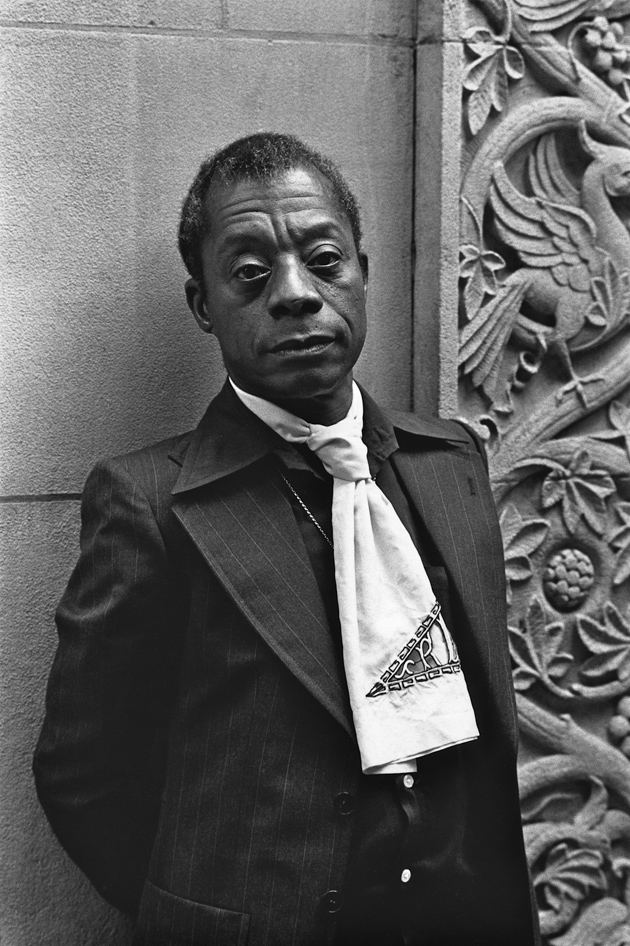

The political goals of the civil rights movement that Baldwin made himself a witness for, as an essayist, novelist, and activist, were partially realized with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Even the angry black nationalists of the 1960s who attacked Baldwin as a queer and a darling of white liberals accomplished something in the long run. They transformed the public psychology of race, combating on an unprecedented scale the dogma of racial inferiority. Still, Baldwin was as fearless an exponent of racial justice as any of the black nationalists. He famously told the startled Robert Kennedy that young blacks could not be expected to serve loyally in the Vietnam War. Consequently, he was hurt when the Black Panthers’ Eldridge Cleaver, in Soul on Ice (1968), wrote that “the racial deathwish” was the driving force in James Baldwin because he, a gay black man, had been “castrated” by the white man, and was, moreover, frustrated in his desire to have a baby by a white man, to absorb a white lover’s whiteness. Baldwin, remembered as controlled, elegant, intense, and polite, refused at the time to show in public how wounding such attacks were.

For all the efforts of black activists, neither poverty nor racism was eradicated, and discrepancies between the standard of living of whites and of blacks only increased over the years. Baldwin died in 1987, when the conservative reaction presided over by Ronald Reagan, “the third-rate, failed, ex–Warner Brothers contract player,” threatened to reverse the gains of what historians sometimes call the Second Reconstruction. Americans were told by some commentators how exhausted they were with the subject of racial justice. “That the western world has forgotten that such a thing as the moral choice exists, my history, my flesh, and my soul bear witness,” Baldwin wrote in “An Open Letter to the Born Again” in 1979 and reprinted in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. For the remainder of his life he seemed one of the casualties of the freedom movement. He would say that what was wrong with the country was still deeply wrong.

The late uncollected pieces that Baldwin included in The Price of the Ticket were written by a man who remembered himself as a youth with “murder in his heart.” Just as Baldwin in his later fiction hoped to have another blockbuster like Another Country (1962), so he could sometimes in his later essays seem to be looking to arouse again the sort of controversy that attended the publication of his inflammatory essay on race relations, The Fire Next Time (1963), much of which had appeared in The New Yorker. In the first issue of The New York Review, F.W. Dupee argued that Baldwin had substituted prophecy for analysis and in so doing risked losing his grasp of his great theme, freedom.1 In retrospect, Baldwin in parts of The Fire Next Time can sound somewhat naive about the political process. He certainly overestimated the concern white Americans had about how racial injustice was affecting the moral atmosphere of the country. But it’s understandable that he believed in 1963 that black people held the key to the nation’s political future: nothing like the mass protests of those days had ever happened before.

Advertisement

Much of the considerable writing on James Baldwin holds that the probings and provocations of Notes of a Native Son (1955), Nobody Knows My Name (1961), and The Fire Next Time are more engaging than the overt expressions of his disillusionment, starting with No Name in the Street (1972). Implicit in the comparison is a judgment about integration and black separatism, as though his nuanced work belongs to a hopeful time of racial dialogue and his excoriations to the simplicity of his militancy. But there has been all along a black resistance, so to speak, to the critical view that there came a falling off in Baldwin’s work once he had given himself over to forever haranguing Western society. He had stirred the waters with The Fire Next Time, and in the run-up to the 1980 presidential election he again sounded some alarmist chords in a futile effort to reignite in black voters a sense of political urgency:

Therefore, in a couple of days, blacks may be using the vote to outwit the Final Solution. Yes. The Final Solution. No black person can afford to forget that the history of this country is genocidal from where the buffalo once roamed to where our ancestors were slaughtered (from New Orleans to New York, from Birmingham to Boston) and to the Caribbean and to Hiroshima and Nagasaki and to Saigon. Oh, yes, let freedom ring.

Black critics, especially, have concentrated on what they see as the valor in such political statements, and they praise his last novels, If Beale Street Could Talk (1973) and Just Above My Head (1979), for being proudly pro-black, for depicting loving and supportive black families. They argue that Baldwin sacrificed his popularity with the white critical establishment because he insisted on telling American society discomfiting truths. The exception is Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), Baldwin’s troubled account of the gruesome Atlanta case in which Wayne Williams was arrested in connection with twenty-eight murders, mostly of children, and was eventually convicted of two of them. Few have defended the book or even tried to explain it.

Meanwhile, young scholars look for something fresh to say about Baldwin, to free him from the biography of his early triumphs leading, by way of the assassinations and violence of the 1960s, to late despair. Because of the passage of time, their distance, they examine Baldwin as someone who shows how white America was influenced by black America, and not just in music, and not the usual other way around, that of whites influencing blacks.

Some of the young scholars who want to reconsider Baldwin also have an interest in gender studies. They revere him not only for his pioneering fiction about homosexuality, but for his meditation on masculinity and constricting American ideas of sexuality, “Here Be Dragons,” published in 1985, one of only two essays to address sexuality directly that he published in his lifetime. Randall Kenan, the editor of The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, is of the generation of young black gay writers for whom Baldwin is a sort of spiritual father.

Baldwin was sure he had to kill off the straightforward realism of Richard Wright in order to heed Henry James, but Kenan didn’t have to set aside his racial identity before he could embrace a queer antecedent. Kenan’s first novel, A Visitation of Spirits (1989), is the coming-of-age story of a black gay youth, and the stories collected in Let the Dead Bury Their Dead (1992) are mostly about what it means to be black, poor, and gay in the South. He has written a biography of Baldwin for young readers, and The Fire This Time (2007) is Kenan’s homage to Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which created a sensation in 1963, the year Kenan was born. Where Baldwin is stirring in denouncing complacent American racism, Kenan’s commentary on what has and has not changed in the racial situation in the US in the years since is tepid, but nevertheless he shows himself a sensitive interpreter of Baldwin’s intentions.

Advertisement

In his introduction to The Cross of Redemption, Kenan says that he had subscribed to the view that Baldwin in his last years was bitter and unhappy:

Journalists often quoted the interviews that Baldwin gave in the late 1960s and early 1970s, at the height of the Vietnam War and in the wake of so much death and an American landscape pockmarked with riot-ruined cities.

However, Kenan feels that Baldwin was still producing outstanding work, including The Devil Finds Work (1976), his retelling of his life through the motion pictures he grew up on; a discussion of the childhood torments caused by his appearance, for instance, is centered on the Bette Davis film 20,000 Years in Sing Sing. As Baldwin moved into the 1980s and then turned sixty, Kenan writes, “life was rich, despite what the media would have led us to believe.”

Kenan means for The Cross of Redemption to be a companion to the Library of America edition of Baldwin’s Collected Essays (1998). The fifty-four previously uncollected pieces range from Baldwin’s earliest book reviews, published in The New Leader in 1947, to his denunciations of the Christian right, written not long before his death. Included are speeches from rallies in the 1960s; open letters, such as his fiery letter in 1970 to Angela Davis when she was incarcerated, in which he declared that “the enormous revolution in black consciousness which has occurred in your generation, my dear sister, means the beginning or the end of America”; and a memoir of playwright Lorraine Hansberry when she, too, confronted Robert Kennedy and asked him for a “moral commitment” to combat racism.

Not everything great writers do has to be great. We are interested in their miscellaneous writing because we want to go on discovering things by them and things about them. Baldwin never fails to move one somehow. Anguish has your number; it knows where you live, he said. Baldwin in his essays depends on what he can bring to bear from his personal history. In this volume, as in all his essays on race and politics, his premise is that the Negro Problem is in fact a white problem. For conditions to improve for black people, profound change would have to come to white America.

Kenan would perhaps say that those people put off by the radicalism of Baldwin’s late phase have not paid close enough attention to how radical he was already early on. The Cross of Redemption reminds us that Baldwin was, indeed, taking white liberals to task for the failures and self-congratulation of their social imagination some time before he was dismissed by black militants as irrelevant and out of date. “The American way of life has failed—to make people happier or to make them better,” Baldwin declared when Eisenhower was in the White House. To become a revolutionary country was the only hope America had, he was saying at the beginning of the Kennedy administration. The standards by which middle-class Americans lived had to be undermined. It was time to create new standards. “What they care about is the continuation of white supremacy, so that white liberals who are with you in principle will move out when you move in.”

Baldwin on race is Baldwin on the white American psyche. He thought a lot about white men. He wants to understand even as he condemns. He consistently attacked them for longing for innocence, for their refusal to grow up, but it was he who seemed the innocent in his demand that America atone, or pay its dues, as he liked to say. The difficulty was not so much that white Americans were unable to admit that genocide—the Middle Passage, the Indian Wars—was an integral part of American history, it was that acceptance of the historical truth was not likely to alter anything, which left Baldwin reiterating and restating his demand for justice down through the years. He won’t give up; America, he believed, was sustaining too much suffering at home and abroad in its willful ignorance of its own and Western history.

Into the 1970s, he was called upon to lend his name, to speak for international political causes in London or Berkeley, challenging his audiences to be better people. His speeches and open letters are time capsules in their rhetoric. Even the ones from his most angry moments aren’t like a militant’s words for black people, to which the white liberal press can listen in. Baldwin assumed an integrated audience. What damaged his tone was that he decided that white people needed things explained on a basic level. Often he sounded like he was scolding a Sunday school classroom.

Not all of the work in The Cross of Redemption is political: we get considered essays on jazz (“This music begins on the auction block”), on the uses of the blues, on the debate about Black English, on mass culture as a reflection of American chaos, on the untruthfulness of American plays and the consequent “nerve-wracking busyness” of the American stage—which spent huge amounts of skill and energy attempting to “justify our fantasies, thus locking us within them.” There are some forewords and afterwords to books about black America, profiles of the Patterson-Liston fight in Chicago in 1963 and of Sidney Poitier in 1968 as well as a spirited defense of Lorraine Hansberry’s best-known work, A Raisin in the Sun. In the pieces on culture, The Cross of Redemption becomes an absorbing portrait of Baldwin’s times—and of him.

In Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin rejected Shakespeare and Chartres Cathedral as symbols of a culture in which he had no part. In “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare,” originally published in the London Observer in 1964 and reprinted in The Cross of Redemption, he said he’d been young and missed the point entirely, because of a “loveless education.” He no longer considered Shakespeare one of the architects of his oppression. “I was resenting, of course, the assault on my simplicity.” If the English language was not his, then, he said, maybe he hadn’t learned how to use it. He finally heard Shakespeare in what he called the “shock” of Julius Caesar. Then, too, Shakespeare’s “bawdiness” mattered to him once he realized that bawdiness, which signified “respect for the body,” was also an element of the jazz he’d been listening to and hoping to “translate” into his work. “The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people. He could have done this only through love.”

Baldwin’s Blues for Mr. Charlie appeared on Broadway in 1964 to mixed reviews. His ambitions in drama were as keen and misplaced as Henry James’s. He’d been Elia Kazan’s assistant at the Actor’s Studio in the late 1940s. The Cross of Redemption includes a memoir of Geraldine Page in rehearsal for Kazan’s production of Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth and Baldwin’s generous review of Kazan’s novel, The Arrangement, published in 1967. Kazan had testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee, but Baldwin was loyal to him and to his memories of the days when he ran the streets of Greenwich Village with the young Marlon Brando. One can feel his period—the Method—in his remarks on theater and in his wanting to jazz up Shakespeare, to vouch for him as a hep cat attuned to what was happening in his Elizabethan streets. Everyone finds in Shakespeare the Shakespeare he or she needs, but it is a surprise how uninteresting on him Baldwin lets himself be, calling him “the last bawdy writer in the English language.”

Also surprising are the book reviews with which Baldwin’s career began. It is not uncommon for young writers to be tough critics as a way of making an impression. They are at the same time boasting or making a wager with the future that they won’t make the mistakes they are grilling their elders for. The twenty-three-year-old Baldwin is merciless to Maxim Gorky. He finds him perceptive but not profound, observant but frequently sentimental: “Gorky does not seem capable of the definitive insight, the shock of identification.”

Baldwin couldn’t take seriously Erskine Caldwell’s latest in 1947, The Sure Hand of God, which he called “curious because of its effortless tone and absolute emptiness,” and regretted that a promising novel about a repressed homosexual turned out to be boring. The Portable Russian Reader is “quite dreadfully comprehensive” and Baldwin is so hostile to James M. Cain’s “moist, benevolent fascination” with the tough guy that his scorn comes across as a generational repudiation of the hard-boiled style of the 1930s. Baldwin’s early reviews fit with his famous attacks on Richard Wright and the protest novel in Notes of a Native Son. He was even more cutting about John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom (1947). In reaching for the objectivity expected of him as “a Negro and a Negro historian,” Franklin “becomes very nearly fatuous and persistently shallow.”

But suddenly Baldwin is talking about something he’s deeply interested in and everything is different, charged with energy. On reading again Robert Louis Stevenson, a favorite of his childhood, he finds him at his absolute best in Kidnapped: “All of Stevenson’s warm brutal innocence is here, the sensation of light and air, the nervous tension, the chase, the victory.” Men were not a riddle to Stevenson; they were fitting subjects for romance and he made them asexual, in the manner of preadolescent youth. This is the Baldwin whose insights are lasting, the writer who in 1963 recalls that as an adolescent he discovered from reading Dostoevsky—not the Bible—that all people are sinners, that suffering is common, and that one’s pain is trivial except insofar as one uses it to connect with the pain of others. He can summon the apt phrase from Henry James (“Live, live all you can. It’s a mistake not to”).

“As Much Truth As One Can Bear,” taken from The New York Times Book Review in 1962, has Baldwin talking with authority and intensity about the sorrow of Gatsby and what the receding green light means for his generation of novelists, and how Hemingway’s “reputation began to be unassailable at the very instant that his work began that decline from which it never recovered—at about the time of For Whom the Bell Tolls.” Faulkner, he observes, is more appalled by the crimes his forebears committed against themselves than he is by the crimes they committed against Negroes, and Dos Passos writes of an American innocence that must be betrayed if the nation is to grow.

Americans use language to cover the sleeper, not to wake him, Baldwin said, which was why the writer as artist is so important. Only the artist could reveal society and help it to renew itself. It never made sense to him to speak following Philip Rahv’s essay of “Paleface and Redface in American Literature,” because he could not think of an American novelist in whom the two traditions were not inextricably intertwined:

One hears, it seems to me, in the work of all American novelists, even including the mighty Henry James, songs of the plains, the memory of a virgin continent, mysteriously despoiled, though all dreams were to have become possible here. This did not happen. And the panic, then, to which I have referred comes out of the fact that we are now confronting the awful question of whether or not all our dreams have failed. How have we managed to become what we have, in fact, become? And if we are, as indeed we seem to be, so empty and so desperate, what are we to do about it? How shall we put ourselves in touch with reality?

After she sat on a book prize committee with Baldwin, Mary McCarthy expressed her astonishment that he had read just about everything. Her surprise would at first seem an insult, but then the literary side of Baldwin is hardly known, compared to the eloquent spokesman for racial justice.

The Cross of Redemption has a notebook-like quality because the pieces are uneven, and in the inclusion of interviews that have Baldwin riffing in one way, testing in another. However, Kenan’s volume suggests more strongly than anything before what we most want in the way of a posthumous Baldwin publication: his letters. The most intriguing selection in the book is “Letters from a Journey,” a series of letters to his agent about a trip to Africa that he planned in 1961, but that he did not take. The series was published in Harper’s in 1963. Baldwin starts out in Israel in September, as a gateway to Africa, but by October he is in Istanbul, full of excuses, asking for money, full of plans, doing everything except going to Africa:

This is one of the reasons I jumped at the Grove Press invitation [to go to Africa]: it gives me a deadline to get out of NY. For I must say, my dear Bob—though I am perhaps excessively melancholy today—one thing which this strange and lonely journey has made me feel even more strongly is that it’s much better for me to try to stay out of the US as much as possible. I really do find American life intolerable and, more than that, personally menacing. I know that I will never be able to expatriate myself again—but I also somehow know that the incessant strain and terror—for me—of continued living there will prove, finally, to be more than I can stand.

This, like all such decisions, is wholly private and unanswerable, probably irrevocable and probably irrational—whatever that last word may mean. What it comes to is that I am already fearfully menaced—within—by my vision and am under the obligation to minimize my dangers. It is one thing to try to become articulate where you are, relatively speaking, left alone to do so and quite another to make this attempt in a setting where the terrors of other people so corroborate your own. I think that I must really reconcile myself to being a transatlantic commuter—and turn to my advantage, and not impossibly the advantage of others, the fact that I am a stranger everywhere.

This is the Baldwin who has sometimes smiled out at us from the pages of his biographers, the writer making up the fabulous figure, Jimmy Baldwin, as he goes along. A few lines in his own words from Turkey have more fascination than Magdalena J. Zaborowska’s recent and impossibly written James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile (2009) can hope to muster. Nothing about him can compete with his own voice. People who have read some of Baldwin’s letters—Hilton Als, one of the most perceptive critics on Baldwin; James Campbell, his best biographer; and Caryl Phillips, a young friend of Baldwin’s in his last years—say that they are among his best work, especially the many he wrote home to his mother during his early days in Paris, and that it is a pity the Baldwin family has not yet published them. They might still have perceived, as Henry James said of Emerson’s confused parishioners, that he was the prayer and the sermon, “not in the least a secularizer, but in his own subtle insinuating way a sanctifier.”

This Issue

November 25, 2010