1.

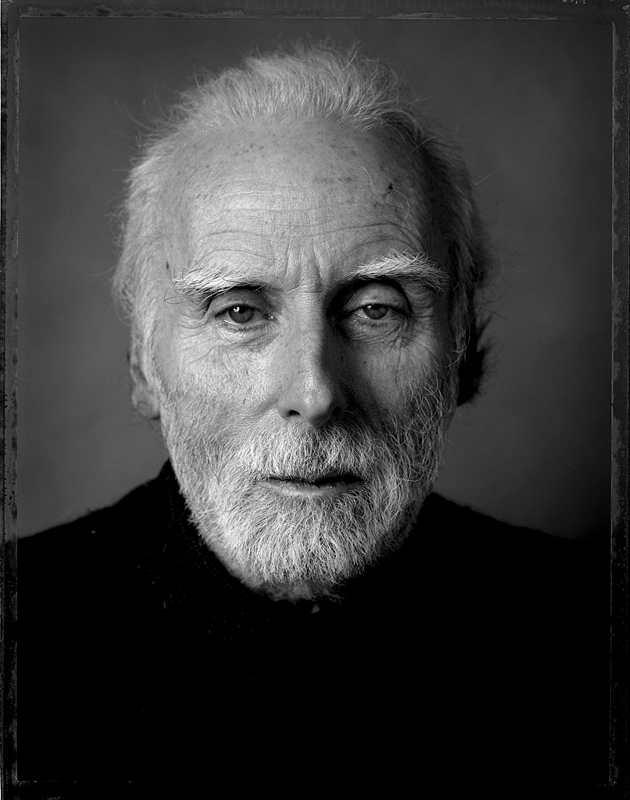

At eighty-five, Jack Gilbert has published just his fifth short collection of poems. Once, around 1962, Gilbert seemed poised to become ubiquitous. His first book, Views of Jeopardy, had won the Yale Younger Poets Prize and was published to wide acclaim. He himself looked great: commanding, intense, a little wounded. It was no doubt the best moment in history for a seriously handsome young poet to come onto the scene. He was profiled in Glamour and Vogue. (Robert Lowell, another handsome poet, had been the subject of a story in Life some years before.) Great photographs of poets were taken in those decades: Cartier-Bresson’s images of Lowell, Nancy Crampton’s shots of Anne Sexton, the images of Dylan Thomas’s American tour, the famous group portrait of poets and writers at a reception for Dame Edith and Sir Osbert Sitwell, at the Gotham Book Mart in 1948.

What happened next brought Gilbert a version of fame different from what fate had prepared: he vanished. He spent years in Greece and then in Japan. He wrote but almost never published, preferring to practical and worldly success different kinds of pleasure: the smells of almond trees in blossom, the sight of some farmers plowing a field. (“He never cared if he was poor or had to sleep on a park bench,” his former companion, Linda Gregg, has written. Some people back home got the idea he was homeless.) His next three books arrived at wide but narrowing intervals: Monolithos in 1982, The Great Fires in 1994, Refusing Heaven in 2005, and now, to everyone’s surprise, a new volume, The Dance Most of All.

Gilbert had performed a trick few poets accomplish without dying: he became a symbol of repudiated worldliness. There is always an audience for visible asceticism, the monk in our midst: Gilbert’s poems showed people a path to livable sensuality, accord with nature, and meaningful, indeed spiritual, carnality. He became that most unusual presence in postmodern poetry, a poet of happiness. The poems were advertisements for a life built upon the bedrock of sex, walks, mellow companionship, and food. His pared-down vocabulary was made up mainly of multiple-use items: “heart,” “body,” “truth,” “love.” It was the vocabulary equivalent of a Swiss army knife. Gilbert did the one big thing early, shunning the American table set for him, and what he has done since has derived from that moment of unconsciously canny myth-crafting. His poems are submitted the way receipts are submitted, after the fact, a little torn and frayed. They are proof of his expenses and evidence of his extraordinary thrift.

It thrills people to hear Gilbert denigrate the modern, mechanical world, the business of poetry, the “dinners and meetings” he says he left behind, the requirement that writers “hang out.” In place of the experience he caricatures in terms of cars, money, mortgages, and children, Gilbert offers a counter-caricature, as though boning branzino and cooling one’s lover’s nipples with shaved ice added up to a feasible life strategy. These activities he designates as “the living,” and importantly he does not include writing poetry among them. Poetry is in fact a potential threat to living: he writes of “not wanting to lose it all for poetry./Wanting to live the living.”

Critics speak of Gilbert in terms of quests, essences, ferocity, the desire to see things (as he put it) “flayed bare.” His poems are indeed accounts of, or perhaps reports from, varieties of intensity. They summarize experience, leaving a little blurriness or abstraction to suggest the idea that “the living” has to happen off the page. It gives his work the curious, deflated air of reported force, of announced, but not evinced, transfiguration. The resulting style that sounds to some like prophecy sounds to others, often to me, like preachiness. His poems deploy their foraged wisdom mainly to demonstrate that foraging for wisdom is wisdom. His survivalist’s aesthetic of thrift and sparsity is too plain and literal-minded an embodiment of a moral curriculum. And some of his most famous poems—I suspect this is the root of their broad appeal—are little motto machines:

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite. Love, we say,

God, we say, Rome and Michiko, we write, and the words

get it wrong. We say bread and it means according

to which nation. French has no word for home,

and we have no word for strict pleasure. A people

in northern India is dying out because their ancient

tongue has no words for endearment. I dream of lost

vocabularies that might express some of what

we no longer can. Maybe the Etruscan texts would

finally explain why the couples on their tombs

are smiling. And maybe not. When the thousands

of mysterious Sumerian tablets were translated,

they seemed to be business records. But what if they

are poems or psalms? My joy is the same as twelve

Ethiopian goats standing silent in the morning light.

O Lord, thou art slabs of salt and ingots of copper,

as grand as ripe barley lithe under the wind’s labor.

Her breasts are six white oxen loaded with bolts

of long-fibered Egyptian cotton. My love is a hundred

pitchers of honey. Shiploads of thuya are what

my body wants to say to your body. Giraffes are this

desire in the dark. Perhaps the spiral Minoan script

is not a language but a map. What we feel most has

no name but amber, archers, cinnamon, horses and birds.

There was probably never a moment in recent culture when this was news: “words/get it all wrong” is a cliché of pop songs, and anyway, the main point of this poem—that language is a poor approximate for feeling—was made by Robert Hass, in “Meditation at Lagunitas,” years before. I know: poems don’t make points. But why then this weird tenacity aimed at nothing, as though anyone could plausibly argue with anything the poem says? My test for poems is often to imagine teaching them: how on earth would one teach a poem like this one, so eager to secure our approval—as though approval could be withheld—for its incontestible claims?

Advertisement

Gilbert’s poems often crest with a catalogue of particulars: “amber, archers, cinnamon, horses, and birds.” Among his profound struggles (and it is a question all serious poets put to themselves) is with what to do with particulars. The trouble for Gilbert is that they have, everywhere, his abstract endorsement. It makes every detail in his work a symbol for the beauty and nobility of the detail: weirdly, the more particular he gets, the more abstract he seems. One manifestation of this problem is his embrace of atrophied landscapes, ruins, traces: “the insignificant/ruins the negligible museums, the back-/country villages with only one pizzeria/and two small bars.” These inventories of endangered details allow his essentially elegiac temperament to attach to sight: seeing is saying goodbye.

The crisis of balancing discrete details against abstract claims contributes to Gilbert’s “woman problem.” His attempts to particularize his erotic life alternate with sometimes preposterous elevations of women—“the woman”—into goddesshood. Gilbert is really a much finer poet than these moments of utter bathos suggest, but so be it. Here are some examples of Gilbert’s writings on women:

I am neither priestly nor tired, and the great knowledge

of breasts with their loud nipples congregates in me.

The sudden nakedness, the small ribs, the mouth.*

She takes her clothes off without excitement.

Her eyes don’t know what to do. There is silence

in the countries of her body, Umbrian hill towns

under those small ribs, foreign voices singing

in the distance of her back.*

Ah, you three women I have loved in this

long life, along with a few others.

And the four I may have loved, or stopped short

of loving. I wander through these woods

making songs of you.

One could get indignant about these poems (some have); one could also make some very amusing remarks. I’ll just point to the awkward shuttling between the absurd elevation or inflation of “women” on the one hand (these women! they make up more than half the population of the globe, but their differences, Gilbert implies, are really trifling when compared to the very nice features they all share!) and, on the other, the overcorporeal, nipples, ribs, napes, smalls of backs. There is no middle ground of tone or figure, just wary commerce between the two poles. Gilbert is considered a great poet of eros: I wish he had never gone near the subject.

2.

What I value in Gilbert is something inextricable from his deep flaws: here is a genuinely uncompromising poet, a poet who likes to struggle—so much so that he often creates his own difficulties. The prospect of his celebrity was too assured back in the early Sixties; therefore he bailed out. His commitment to primitive values, his small, repetitive vocabulary, his nipple and rib fixations, all of these are ways of setting, for himself, nearly impossible odds. The poems that result—however delicately attentive to love and loss—are tributes to inspired stubbornness. Practically everything tagged “moving” in Gilbert leaves me cold. But the effect of seeing a person wring art out of such dry sources is very moving indeed.

Life has, of late, conspired with Gilbert to make the odds even longer. It is widely known that he struggles with dementia: nobody anticipated another book after 2005’s Refusing Heaven. In a Paris Review interview, conducted after that book’s publication, Gilbert mused about writing “something about getting old. It’s never been explored appropriately.” That’s not so: even just among living poets, we have at this moment several accounts of getting old, from sources as different as Richard Wilbur, John Ashbery, Adrienne Rich, David Ferry, W.S. Merwin…the list goes on, but the fact of the matter is, more poets of consequence than ever before have lived and written into their eighties and beyond.

Advertisement

Add Gilbert to that list. His last two books are his best, and they are at their best when treating the pungent material of Gilbert’s Pittsburgh childhood. Gilbert once dismissed writers who, lacking any other subject, “write the same stories about their childhood over and over.” Pittsburgh has been a presence all along in his work, but these poems retrieve a world and ambience new to poetry: the old vaudeville theaters rechristened as burlesque houses, “grand gestures of huge chandeliers…and the ceilings hanging in tatters,” old men “from their one room/(with its single, forbidden gas range)/to watch the strippers.” Or the family’s mansion on the outskirts of Pittsburgh:

He wonders why he can’t remember the blossoming.

He can taste the brightness of the sour-cherry trees,

but not the clamoring whiteness. He was seven in

the first grade. He remembers two years later when

they were alone in those rich days. He and his sister

in what they called kindergarten.

They played every day on the towering

slate roofs. Barefoot. No one to see them on

those fine days. He remembers the fear

when they shot through the copper-sheeted

tunnels through the house. The fear

and joy and not getting hurt. Being tangled

high up in the mansion’s Bing cherry tree with

its luscious fruit. Remembers

the lavish blooming. Remembers the caves they

built in the cellar, in the masses of clothing and draperies.

The poem about childhood innocence, like the innocence it describes, ends with the arrival of an adult, Gilbert’s unsettlingly jolly, drunken father:

It was always summer, except for

the night when his father suddenly appeared. Bursting

in with crates of oranges or eggs, laughing in a way

that thrilled them. The snowy night behind him.

Who never brought two pounds of anything. The boy remembers

the drunkenness but not how he felt about it,

except for the Christmas when his father tried to embrace

the tree when he came home. Thousands of lights,

endless tinsel and ornaments. He does

not remember any of it except the crash as his father

went down. The end of something.

Gilbert’s old habit of alternately under- and overdescribing here feels precisely instrumental in exploring paradoxes of memory and representation that only poetry brings to light. Gilbert “can’t remember the blossoming” that he nevertheless describes (“the clamoring whiteness”), nor can he remember “how he felt about” his father’s drunkenness, even though the poem is of course saturated with his feelings about it and everything else in that house, in that time. It is one of many poems in The Dance Most of All that suggest Gilbert’s legacy: as a poet of memory, as distinct from present-tense lived life; as a theorist—despite his intention to keep life from settling into language—of language and its limits; and as an American poet after all, the greatest poet of Pittsburgh.

This Issue

December 9, 2010