The Bengal famine of 1943, which extinguished as many as three million lives in pre-partition British India, was the last (but hardly the first) such social catastrophe to erupt under the Raj. It has since been closely studied and analyzed—preeminently by the Bengali economist and social thinker Amartya Sen, who as a youngster witnessed firsthand the desperation of starving agricultural laborers with nothing to exchange for a meager bowl of rice. Independent India has shown a hardy indifference to mass malnutrition at the bottom of its social pyramid and has once or twice skated near the edge of famine. But though its population has nearly tripled over six decades, it has avoided anything approaching the failure of 1943. Democratic self-government and freedom of speech, Sen famously concluded, have made the difference, bringing pressure on authorities to make the relatively small shifts of resources and emergency employment opportunities that are usually enough to hold at bay starvation and the ravaging diseases that accompany it. “Famines are, in fact, so easy to prevent,” Sen writes, “that it is amazing that they are allowed to occur at all.”

Madhusree Mukerjee, a younger Bengali who experienced the 1943 famine secondhand through recollections of relatives and neighbors, still stands amazed. She’s eager to personify and corner what Sen carefully calls “the role of human agency” in his catalog of various economic and social ingredients that may make a famine. Her quarry is Winston Churchill. If not the prime mover of the famine, the embattled wartime leader was at least responsible, we’re told, for a series of decisions “that would tilt the balance between life and death for millions.” Put another way, in her opening paragraph, “one primary cause” of the famine was the Briton’s readiness “to use the resources of India to wage war against Germany and Japan.”

Mukerjee wants to make readers aware that “apart from the United Kingdom itself, India would become the largest contributor to the empire’s war, providing goods and services worth more than £2 billion.” (Included in this total were the cost of supporting British forces made up largely of Indian sepoys in Iraq as well as on the subcontinent itself, plus credits from the colonial treasury—loans that one day would have to be repaid—to the mother country’s strained exchequer.) On the matter of the famine, her wording may sound a little tricky. “One primary cause” is not the same as “the primary cause” but it comes close enough to provide scaffolding for her accusatory title. Probably it’s true that fewer Bengalis would have died had Churchill approved an emergency request from his own officials in India in July 1943 for shipments of 80,000 tons of wheat a month to Bengal for the rest of the year. Whether his failure to do so amounts to a “secret war” is another question.

At first glance, Mukerjee’s book is a detailed working out of Amartya Sen’s proposition that a democratic government will preserve its people better than a regime that rules from afar. The author, a science journalist now resident in Germany, has delved into transcripts of meetings of Churchill’s “war cabinet” (not made available until 20061) and papers of his secretary of state for India, Leopold Amery (opened in 1997), to elaborate in considerable detail on the already well-known story of Churchill’s reluctance over more than ten months to authorize British ships to carry emergency food supplies to Bengal. In a 1943 diary note published thirty-five years ago, Lord Wavell, the penultimate British viceroy, called the attitude toward India of Churchill’s government—by which he really meant the prime minister himself—“negligent, hostile and contemptuous.”

From Mukerjee we now get every episode of Churchill’s ugly self-caricature, the tirades he could be counted on to throw whenever the subjects of India, Hindus, or Gandhi distracted the old imperialist’s attention from the home front or the war in Europe. (In a typical fulmination, directed at an American emissary, Churchill threatened to resign if President Roosevelt kept second-guessing him on India’s future. FDR concluded that it was hopeless to press further.)

Here such eruptions are tied by Mukerjee to specific decisions by British authorities barring the diversion of British ships carrying Australian and American food stocks to ports in eastern India. The question was whether the saving of Indian lives could be addressed as a wartime aim with the same urgency as the saving of British or even Balkan lives. Churchill found the question intolerable, almost maddening, to the point that an exasperated Amery wrote in his diary: “I am by no means quite sure whether on this subject of India he is really quite sane.” Amery’s own credentials as an imperialist were beyond question, but he was prepared to apply a measure of pragmatism to the problem of how best to engage India in the war effort. When he was not questioning the prime minister’s sanity, the secretary of state privately explained him as a throwback to the Victorian era of his youth, writing of “Winston’s refusal to accept things as they are and not as they were in 1895,” an insight that has been frequently echoed.

Advertisement

No one ignited the fury that Churchill brought to any discussion of Indian issues more reliably than Mahatma Gandhi. The two men had met only once, briefly in 1906 when Gandhi was a well-dressed barrister, not a Mahatma. Yet in Churchill’s eyes he stood out in his later guise as a “malignant subversive fanatic” and “thoroughly evil force, hostile to us in every fiber.” His level of vituperation when the Mahatma is mentioned in war cabinet meetings is something to behold. Gandhi is “the world’s most successful humbug.” When in 1943 the imprisoned Mahatma threatens a fast, the prime minister orders Amery to be sure he’s told that “we had no objections to his fasting to death if he wanted to.”

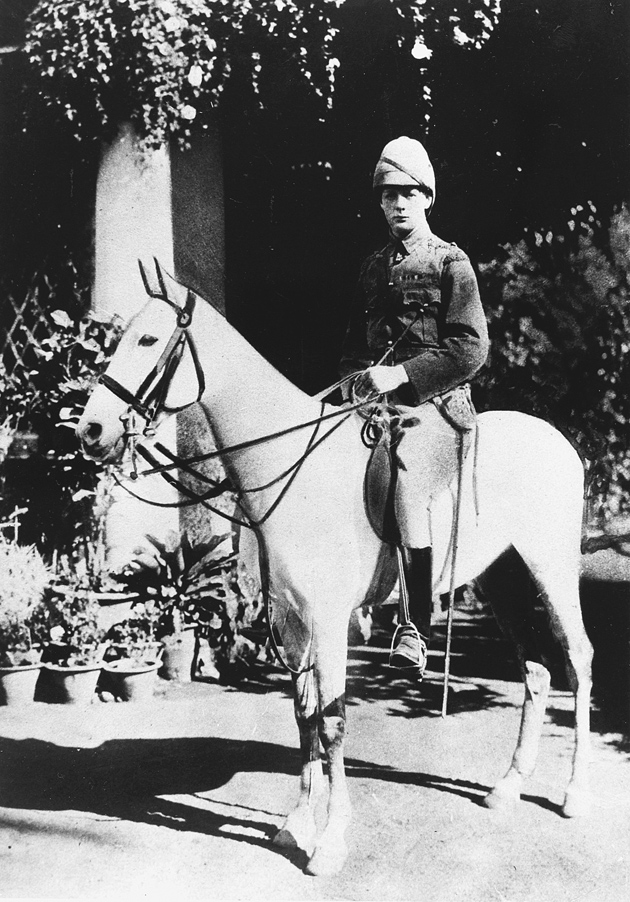

When he then doesn’t die, Churchill demands an explanation from the viceroy. What he wants to be told is that Gandhi has been cheating, taking nourishment on the side. He doesn’t get any evidence to support his suspicion but later repeats the accusation in his memoirs. It’s not clear whether Churchill’s sense of Hindus is an extrapolation on a subcontinental scale from his impression of Gandhi or whether it’s the other way around, with his impressions of Gandhi encapsulating prejudices against Hindus brought back from his service as a cavalryman in India for a couple of years, starting in 1896. Hindus, he grumbled, “were a beastly people with a beastly religion.” Or again, “the beastliest people in the world next to the Germans.”

So if the argument is that no one was less likely to be Bengal’s savior at the start of 1943 when the danger of famine first became apparent to responsible colonial officials, then, clearly, there’s no defense for Churchill. But for all his fulminations, do his conspicuous acts of omission—his failure to dispatch emergency shipments—add up to anything approaching a “secret war”? In justifying her flaming title, Mukerjee seems to skirt the key conclusion reached by Amartya Sen long after the crisis: that it had little to do with an actual shortage of food in the stricken province.

Mukerjee is understandably incensed by the imperviousness of Churchill to the pleas to alleviate the famine from his top advisers on India, Amery and two successive viceroys, Lords Linlithgow and Wavell; and by his reliance on his science adviser, Lord Cherwell (known to the academic world as Frederick Lindemann before snaring his peerage), whose sycophancy and instinctive racism were usually apparent. Cherwell, portrayed here as an advocate of race-based eugenics, could be depended on to tell the prime minister what he wanted to hear: that the food crisis in India could be dealt with without diverting ships or dipping into stocks already designated for other theaters.

Cherwell’s motives may have been suspect but Mukerjee insufficiently engages his analysis, which led him to conclusions broadly similar to those reached by Amartya Sen after careful study three decades later. Although the war cut off some sources of imported grains, there were in fact stored supplies of food that were being hoarded by Indians who hoped to sell them at higher prices. Food prices shot up to the extreme detriment of rural Bengalis “with very little overall decline,” Sen found, “in food output or aggregate supply.” In Cherwell’s view, imports were being sought to serve as a blunt instrument to break a price spiral that the colonial authorities had themselves triggered in their ineffectual attempts to control the price of food; in other words imports would be used, Cherwell wrote, “as a means of extracting food from hoarders.” There were more direct ways to deal with the problem, Cherwell argued, for example seizing the hoarded stocks, even hanging some hoarders. Making a similar point in a decidedly more gentle way, Sen notes the effectiveness in post-independence India of temporary large-scale employment schemes as a way of getting sufficient funds to endangered families in order to stabilize prices and prevent panic.

Nothing can exonerate Cherwell—and Churchill—from charges of aggravated aloofness or indifference. Obviously, it’s an understatement to say that the welfare of Bengalis wasn’t one of their priorities in 1943. But the collision of disasters that produced the famine had already occurred by the time it became an agenda item in its own right for the war cabinet in Whitehall. First came the fall of Burma, with its rice surplus, to the Japanese in March 1942, which raised the possibility of Japanese attacks in eastern India, if only to pin down British troops there. In the next few months, Japanese warplanes made a series of small runs over Calcutta and other sites in the region, spreading a sense of alarm among the British, who decided that there was a military need to remove food stocks and shipping from a half-dozen districts along Bengal’s coast in order to make it harder for an invader to live off the land. This was termed a policy of “denial.” A year later, it would be the local population, not any invaders, that would be denied.

Advertisement

Burma’s fall cut off not only Bengal but also Ceylon, as Sri Lanka then was known, from the nearest, most obvious source of food shipments. Ceylon was vital as a source of the rubber that went into the tires of Allied military vehicles. By 1943, there would be reports of falling production caused by hunger among workers on the island’s rubber plantations. India was expected to make up the losses of food supplies. Meantime, in October 1942, a powerful cyclone had devastated the Bengali coast east of Calcutta, followed by torrential rains that flooded more than seven thousand villages and ruined one harvest in an area on which “denial” had all too effectively been imposed.

With the war effort as their primary concern, British officials had easily persuaded themselves that the suppression of the Indian national movement had become a military imperative. Thus Gandhi, Nehru, and the other leaders were all in jail as Bengal’s gruesome pageant of misery unfolded. Feeding the troops—now being concentrated in eastern India for the eventual counterattack on Burma and support of the airlift over “the hump” to Allied and Chinese forces headquartered in Chongqing—while ensuring that enough rice reached Calcutta to avoid urban unrest also shaped up as obvious military priorities. The colonial authorities did an efficient job of making sure that Calcutta’s industrial and government workers—more than a million of them—had access to subsidized rice through “controlled” shops at their workplaces. They then imposed price controls and, when these didn’t work, tried decontrol, eventually buying up rice stocks at any price, distorting the price mechanism to such a degree that rice, tripling in price over a few months, was suddenly out of reach to millions, particularly those outside the cities. Basically, the British authorities had no policy for relieving the hunger as it spread in rural areas despite the fact that the Raj had adopted a prescriptive Famine Code in 1883, which called for work schemes and the distribution of free food in stricken regions.

In his 1981 study, Poverty and Famines, Amartya Sen notes that the code was never invoked in rural Bengal. The province’s British governor dispatched a clinical assessment to Whitehall. Hunger in the hinterland, he said,

does not constitute grave menace to peace or tranquility of Bengal or any part thereof, for sufferers are entirely submissive and emergency threatens, not maintenance of law and order, but public health and economic stability.

Under the circumstances, this seems to have been received in London not as a blood-chilling bulletin but common-sense reassurance.

Madhusree Mukerjee not only writes well, she writes from a point of view that most Bengalis and many Indians would share. The British for her are not allies; with few exceptions, they’re bumbling colonial oppressors whose reserves of compassion are in perpetual deficit. Nor are the Japanese portrayed as the “enemy,” especially after the Bengali nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose allies himself with them, proclaiming the formation of an Indian National Army that eventually sends thousands of Indian soldiers recruited in prisoner-of-war camps in Southeast Asia into combat alongside the Japanese in Burma where many of them are killed, thinking they are fighting to liberate India. However unsuccessful it proved to be, Bose’s martial performance—a relief for many from the wet blanket of Gandhian nonviolence—made him a hero on a national scale.

Sometimes Mukerjee has to press down hard to force the pieces of her jigsaw into spaces where they don’t easily fit; but in offering a contrasting, if not an alternative narrative, she highlights limitations in the one with which most of us grew up. If the deaths of three million Bengalis can be seen as an unfortunate byproduct of hard choices made by well-intentioned, reasonable men in wartime, then we’re also confronted with a horror that deserves to rank with the bombings of Dresden and Nagasaki.

That is what Mukerjee comes close to accomplishing in her wrenching summary of the sufferings of actual victims: mothers who put their children up for sale, then their own bodies, as starvation loomed. She writes of packs of dogs loping through ravaged villages preying on infants, the enfeebled, and the aged while they still breathed. “Despite the horrific ways in which they met their ends, those Bengalis who perished of hunger in the villages did so in obscurity,” she says, “all but unnoticed by the national and international press.”

Only when skeletal refugees from the countryside started showing up in large numbers to beg—and not infrequently die—on the sidewalks of Calcutta did images of the catastrophe begin to catch the attention of the world beyond Bengal. Local officials responded by seeking to remove the spectacle, rounding up the sufferers under a hastily enacted set of regulations called the Bengal Destitute Persons Ordinance and trucking them to the outskirts of the city in order to hide them from view and thereby sustain the morale of all those deemed vital to the war effort.

In Sen’s account, attempts by British officials to calculate the extent of the food shortage was “a search in the dark for a black cat which wasn’t there.” What the officials faced was not a shortage of food but an economic blowout, a breakdown of price and wage mechanisms that made ordinary commerce possible. The point of emergency wheat shipments would have been to enable direct relief to the starving, which, even without imports, would have been possible earlier if the British had understood what they were facing and if they had sufficiently cared. By the time famine deaths started to peak at the end of 1943, Bengal was bringing in a bumper winter rice harvest. Even that was not a solution; deaths attributable to famine—now accompanied by cholera, malaria, and smallpox—continued at a high level throughout 1944.

Mukerjee has a tendency to indulge in magical thinking to belabor a point: for instance, she writes that the famine might have been prevented or deferred if the 1942 winter rice harvest “had been distributed evenly”; or that if the export to Ceylon and the Middle East of 71,000 tons of rice in early 1943 had been halted, that would have been enough to keep “390,000 people alive for a full year.” The essence of the problem was that there was no mechanism for distributing food grains evenly; that, rather than any imagined shortfall, was the only logical basis of the appeals for emergency relief. “No matter how famine is caused,” Sen wrote in Poverty and Famines, “methods of breaking it call for a large supply of food in the public distribution system.” Put another way, the failure and callousness of colonial administration were the best arguments for emergency relief, but they were arguments the colonial authorities didn’t want to make to the war cabinet; and the war cabinet, headed by a die-hard imperialist, didn’t want to hear them.

There’s a sizable academic literature on the Great Bengal Famine, as it’s called, and, of course, a much more extensive consideration of it in Bengali literature. Madhusree Mukerjee’s treatment appears to be the only account addressed to general readers in English, and while it’s possible to argue that she overstates the cost in lives of Churchill’s reflexive animus toward Gandhi and Hindus, her book should be welcomed as a serious attempt to deal in all its aspects with a neglected catastrophe in an era of catastrophes piled grotesquely one on top of another.

Twenty-three years later the same dismal tale was played out to a notably different conclusion. Famine threatened in the state of Bihar, which neighbors West Bengal (the Indian rump state left over from partition). The British had packed up and gone but the Americans were now on the scene and they had a legislative instrument known as Public Law 480 that allowed them to sell surplus wheat from the US farm belt for Indian rupees. Every month in the winter of 1966–1967, Indian and American officials in New Delhi calculated how much American wheat would be needed to stave off famine in Bihar; and every month, their requests sat on the desk of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who cared for Indira Gandhi, then in her first year as premier, only slightly more than Winston Churchill cared for the Mahatma.

Like Churchill, Johnson was convinced that India had the means to deal with the crisis on its own, if only it would try. So he delayed the shipments for weeks on end as senators from the Midwest wrung their hands over the fate of Bihar and correspondents in New Delhi, egged on by Ambassador Chester Bowles, sent alarming reports about the rising risk of famine. (I know because I was one of them.) Whether this was pique or tough love on Johnson’s part, Mrs. Gandhi was so insulted by being forced, month after month, into the role of supplicant that she was soon talking of self-reliance as a national imperative. Bihar was very hungry in the summer of 1967 but relatively few people starved and India never again went begging for surplus food.

This Issue

December 23, 2010

-

*

The released war cabinet transcripts run through mid-July 1943, Mukerjee says. The transcript of a crucial meeting on August 4, 1943, has yet to be released. ↩