Victoria and Albert Museum, London

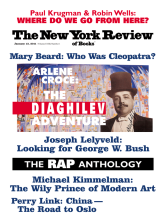

Serge Lifar as Apollo and Alexandra Danilova as Terpsichore in Igor Stravinsky and George Balanchine’s Apollon musagète, 1928; photograph by Sasha. Arlene Croce writes that this ballet, first performed by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, was ‘the supreme example’ of neoclassicism, ‘which broke decisively with the past by reimagining it.’

In the 1930s, when he was trying to establish American ballet, Lincoln Kirstein complained that “balletrusse” was one word. Successor companies to the defunct Franco-Russian Ballets Russes, cashing in on its name and legend, were spreading themselves across the globe. Perhaps today in the public mind ballet is still Russian. When the Soviet Union fell and its ballet companies freed themselves from government interference, the Western choreographer whose works they chose to be their main guide to modernism was George Balanchine, a Ballets Russes product who had been Kirstein’s choice sixty years before, his gift to America.

If the goal of the formerly Soviet companies was to become modern in russe terms, by rights they should have chosen Merce Cunningham, because most Ballets Russes choreography was not ballet but what we would call modern dance. Now that modernism is dead and modern dance is a chapter in history (like Romantic ballet), we look back at ballets we cannot see and try to reconjure an image of stage magic from composites of scenery, costumes, and music. Since that is basically how they were conceived by their own producer, it is not surprising that the latest book about Sergei Diaghilev has no dance commentary to speak of. This is both an understandable omission and a missed opportunity.

Sjeng Scheijen’s field is Russian art, and he locates Diaghilev’s emergence in fin-de-siècle St. Petersburg, at a time when Russian art was at its most Russian. Diaghilev at twenty-one had never had anything to do with ballet. He was not even a balletomane. He was a serious musician, an opera-lover who had trained to be a singer, a self-taught art historian, and a theater aesthete whose certitudes were rooted in the principle of the Gesamtkunstwerk as promulgated by Wagner. It was one of his closest associates, Walter Nouvel, who looked to the future and saw that

that vague, inexpressible, elusive feeling, to which modern literature is trying to give voice, obeying the clamorous demands of the modern spirit, must find, and in all likelihood will find, its realisation in ballet.

Diaghilev came to agree with Nouvel that ballet rather than opera was potentially the vehicle for the fusion of the arts, but when he organized the repertory of the Ballets Russes, his philosophy and his own artistic predilections combined to place a higher value on the music, the scenery, and the story than on the choreography. Not that he disdained choreographers; he simply regarded them as technicians who could be instructed by artists—by himself if necessary.

Scheijen tends to treat his hero as a unique phenomenon, but Diaghilev wasn’t the only one of that inflamed post-Wagnerian generation who thought of himself as an all-purpose man of the theater. That conviction ran right through the top line of theater directors, conductors, and composers, and took in nontheatrical artists as well, saturating the times with multivirtuosic ambition. Strauss and von Hofmannsthal. Reinhardt. Meyerhold. Tairov. Eisenstein. Diaghilev set a painter, Mikhail Larionov, to guide the fledgling choreographer Léonide Massine. Jean Cocteau began as a Diaghilev camp follower. The belief common to all was that ballet, the classical academic dance, was nothing but technique, passionless, mechanical, dead. Even the academically trained, poetically gifted Mikhail Fokine, who was the Ballets Russes’ first choreographer, thought so. (Inside Fokine was the duende of Isadora Duncan.)

The moment was at hand for a new kind of dance. Scheijen sees the moment, and he sees Diaghilev taking hold of it—finding a young male dancer (the seventeen-year-old Nijinsky for starters), bonding with him body and soul, lecturing him on art, escorting him to concerts and galleries, providing whatever supplementary theatrical training he needed; and then there he’d be, someone who could animate the envisioned spectacle to the satisfaction of his mentor and even (as Diaghilev demanded of Cocteau) surprise him. Diaghilev’s attempt to insert himself into the choreographic process of Nijinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps was disastrous, but he learned from it. After getting Massine on his feet, he let him alone, and he didn’t interfere either with Nijinska, his only female choreographer, or Balanchine, his last one.

It is what, in a positive sense, Diaghilev learned from his immersion in dance that we wish we could know. In that sense, he is us, the audience—an onlooker curious about the mysteries of the craft/art that lay at the lowliest depth of the theatrical pyramid yet without which it could not stand. A biographer may of course select aspects of his subject and ignore others, and Scheijen has permission to ignore dance from Diaghilev himself, who after one of his fights with Fokine was heard to boast, “I could make a choreographer out of this inkwell if I wanted to.”

Advertisement

But Scheijen also ignores it because it is a subject about which educated people, after a whole century of revelatory dance, are far more content to remain ignorant than they were at its inception. Granted, dance is the perishable art. Yet of all the Russian ballets that were produced between 1909 and 1929, it’s the ones with the strongest dance content that remain revivable today—Fokine’s Les Sylphides, Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, Nijinska’s Les Noces, Balanchine’s Apollo and The Prodigal Son. All the rest have gone to museum heaven.

But when dance is minimized, there’s a lot of Diaghileviana left over. The Victoria and Albert Museum has issued a thick commemorative album in connection with its current mammoth exhibition of Ballets Russes art, which runs through January 9. Scheijen’s biography presents new material from the Diaghilev archives in Russia. His method of narration through documentation succeeds up to a point. It allows his subject to paint his own portrait in exuberant, delightfully self-aware letters to his adored stepmother, Yelena Diaghileva. Self-revelation continues in the outspoken critical reviews Diaghilev wrote for Mir iskusstva (The World of Art), the arts magazine he founded in 1898 and edited until 1904. It is when he starts exporting Russian art and the saisons russes are launched, followed by the creation of a permanent touring company, that the self-portrait dissolves, and the book becomes a rerun of Diaghilev’s frenetic activities season by season, as seen by Scheijen and an extensive list of voluble Ballets Russes observers and stars.

This quasi-anthological scheme will undoubtedly appeal to readers encountering Diaghilev for the first time. Scheijen’s text avoids the overload of names, dates, and places that sank Richard Buckle’s Diaghilev in 1979, but his approach is nowhere as sophisticated, his interpretive skills never as refined as Buckle’s. His contribution is to have digested the totality of the Diaghilev literature, investigated its claims, and condensed its major findings in a comfortable yet compelling read. When I say “Diaghilev literature,” I mean to include the library of books by or about Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Bakst, Benois, Picasso, Cocteau, Chanel, Matisse, Nijinska, Massine—in short, everyone who worked for the Ballets Russes or had some significant contact with it, such as Misia Sert, Count Harry Kessler, and Gerald and Sara Murphy. For Scheijen, no detail is too small. He even checks out Nijinsky’s assertion that Diaghilev dyed his hair. Rivalries within the Diaghilev camp are examined and enmities traced, most of the time profitably; the profile that emerges of the densely emotional, ever combative Alexandre Benois, the coauthor of Petrushka, is definitive. Diaghilev’s own profile is blurry. The new material, while welcome, isn’t enough, or isn’t weighted enough, to support a novel interpretation of the man’s character and destiny, which is what Scheijen seems to be aiming at. The inevitable conclusion, that Diaghilev was “a man of contradictions,” is not a conclusion so much as it is the outcome of the contradictory opinions expressed throughout the book by a horde of correspondents and memoirists.

One reason the section on Diaghilev’s early years fails to impress is that it is very much what we might have expected. It’s true that, arriving in St. Petersburg, he had to make up for his provincial background, but the old picture of a country bumpkin from Perm, a fair-sized town at the foot of the Ural Mountains, was never credible. Diaghilev’s father, a former cavalry officer, was a devoted amateur musician. His grandfather built the town’s main church, some say also the opera house. The family owned the local vodka distilleries and had a mansion on Perm’s main street and a very large estate in the country. Both houses were continually filled with the music and laughter of friends and relatives, led by Sergei’s father and stepmother. Sergei’s mother died when he was three months old (not in childbirth from the size of his head, as he told people later in life). He loved his stepmother Yelena and his two younger half-brothers.

Scheijen has one big piece of information to add to Buckle’s spectacle of family life: when Diaghilev was seventeen, his feckless father went bankrupt. Everything was sold—the distilleries, the house, the estate, the paintings, the pianos. Beginning with his father’s downfall, the story becomes familiar, Diaghilev’s life following a pattern whereby adversity creates opportunity. Having lost his ancestral home, he moved to St. Petersburg, where, with his fellow students Benois and Nouvel, his cousin and first love Dima Filosofov, and their friend Léon Bakst, he formed the nucleus of Mir iskusstva. (That they probably never did call themselves the Nevsky Pickwickians is sad news.) Of Diaghilev’s critical articles Scheijen observes:

Advertisement

He never doubted his talent as a critic, but it was that very talent that all too often reminded him of his own creative shortcomings. His failure as a composer helped him realise that his genius lay not in artistic creation, but in perceiving the genius of others.

It is doubtful that Diaghilev the critic thought that he was not an artist. One would not know from Scheijen that the influence of Oscar Wilde went deeper than sexuality. Perhaps the most important document cited in the book is “Difficult Questions,” the long, caustic, penetrating essay on aesthetics in which Diaghilev explained the editorial position of the Miriskusniki and which Scheijen presents without mentioning that “our creed”—“the exaltation and glorification of individualism in art”—came from Wilde: “A work of art is the unique result of a unique temperament. Its beauty comes from the fact that the author is what he is.” Diaghilev at all times was what he was.

He made his name with a series of elegantly mounted, provocative art exhibitions, but Diaghilev wanted more than renown, he wanted power. On his way up the institutional ladder—the arts were run by government bureaucracies—he was shot down by entrenched reactionaries, and his career in Russia was over almost before it began. This catastrophe precipitated his decisive move into Western Europe, and the campaigns in Paris on behalf of Russian art, music, and dance began in 1906. Diaghilev was thirty-four, although his Promethean aspirations had been formed a decade earlier. He overcame another crisis when war broke out, forcing the dispersal of his by now very famous dance company. Diaghilev’s fame spread back to Russia, where it earned him nothing but loathing as an opportunist and a scandalmonger. Not until close to the end of his life did he give up his dream of touring Russia with the Ballets Russes.

“A man of contradictions” is what Diaghilev called himself, but his towering achievements would suggest that the ability to resolve contradictions, both within himself and within the arts culture, was his mark of greatness. The flexibility of his judgments of art and artists accounted as much as any other factor for the survival of the Ballets Russes after the war and through the Twenties. Any successful director of an arts institution is a pragmatist, and Diaghilev was no exception, but it wasn’t only pragmatism, much less cynicism, that brought him to sponsor Satie and Poulenc after having launched Stravinsky and Prokofiev. Scheijen is shocked by what he views as Diaghilev’s brazenness in attacking Vladimir Stasov, Russia’s leading spokesman of social activism in art, and then trying to enlist him as a contributor to Mir iskusstva. That Diaghilev could find room in his mind for French musiquette as well as fiery Russianism, that he could impugn Stasov’s ideology and at the same time honestly admire and wish to annex his talent, are possibilities Scheijen doesn’t consider.

Similarly with the Ballets Russes repertory. For Scheijen Parade and Les Noces and Le Pas d’Acier are “progressive.” Schéhérazade and The Firebird and anything to do with the eighteenth century, Diaghilev’s favorite historical era, are “conservative.” In these politicized judgments Scheijen echoes and amplifies the line taken by Lynn Garafola in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (1989). Diaghilev is always carrying art boldly forward or shamefully backward. Going forward by going backward, one of the most revealing strategies of modernism, is given no notice here. Diaghilev was the great pivotal figure between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries and between early and late modernism. It is true that sometimes he supported tradition and sometimes he wrung its neck. He was the first to offend a staid, defensive public with radical art and the first to offend radicals who confused tradition with convention and convention with cliché. But his premieres seldom fell wholly into one slot or the other. They were embodiments of a musical, volatile, dynamic aesthetic, functioning on the highest level of theater, far beyond journalistic categories.

Diaghilev’s personality was an extension of this aesthetic (or the other way around). He appears to have been a born controversialist. If he could resolve contradictions, he could also lose his balance between extremes. His letters to his colleagues are warm and lovingly solicitous; even so, he manages to antagonize nearly everyone who wanted to be, and could be, of use to him—not only Nijinsky, Fokine, Benois, and Bakst, but also Ravel and Stravinsky. His scandals are the basis of his enduring celebrity. His promotion of the avant-garde art of all nations coupled with his rather too conspicuous homosexuality got him in trouble less often than his reputation might lead one to think, but he was brash enough to have had two major public scandals in one year, 1913, both involving his favorite, Nijinsky: the opening night of Sacre, when the art snobs of Paris rioted, and Nijinsky’s secret marriage, to which the flouted lover reacted by summarily dismissing his greatest star.

To his credit, Scheijen is not lured by present-day revisionism into assuming that Nijinsky’s Sacre is a lost masterpiece. His vignettes of the dancer in later years, his mind gone dark, are haunting. But he leaves the reader with a somewhat sour impression of Nijinsky. Far from being an innocent victim of Diaghilev’s manipulations, Nijinsky is manipulative in his own right, haughty and dictatorial. To a less flagrant degree, the same is true of Picasso. Stravinsky is a tragic figure, torn by his need for Vera Sudeikina and his infidelity to Katerina, the mother of his four children.

Among Diaghilev’s pets, only Massine comes off with honors. I don’t quite know why. Scheijen’s statement that Massine’s “progressive” version of Sacre (1920) killed off the Gesamtkunstwerk in ballet and shaped the company’s aesthetic “for the rest of [its] days” is perplexing. What was The Prodigal Son, what were Massine’s own Le Pas d’Acier and Ode, not to mention his post-Diaghilev works, such as Nobilissima Visione, Gaîté Parisienne, and Le Beau Danube, if not striking examples of the Gesamtkunstwerk?

Diaghilev was sexually attracted to boys and didn’t hide it, but attempts to make him into an early champion of gay rights may be misbegotten. Diaghilev was not just an “assertive homosexual,” he was a proselytizing, misogynistic homosexual. Neither Oliver Winchester’s article, “Diaghilev’s Boys,” in the V&A volume nor Scheijen’s biography includes the damning testimony given by Balanchine and Stravinsky on this point. Diaghilev’s misogyny was probably exacerbated by lovers who repeatedly left him for women. Like Nijinsky, Massine became heterosexual as he matured. His womanizing drove Diaghilev almost literally crazy. His response to Massine’s affair with the dancer Vera Savina was to get her drunk, force her to strip, and throw her bodily into bed with Massine, shouting, “Behold your beau ideal!”

From his interviews with Diaghilev’s descendants in Perm, Scheijen obtained valuable information about the family’s suffering under the Bolsheviks. In 1927, Sergei’s half-brother Valentin disappeared from his home in Leningrad/St. Petersburg. In exile since 1914, leader of an organization that had become the cynosure of Paris’s White Russian colony and as such a target of the Soviet government, Diaghilev could find out nothing. His homeland had shut down. He sought help from the French embassy in Moscow, but spoke to none of his confidants about the matter—not even Nouvel, who had been back to Russia and knew firsthand the miseries being endured there.

Judging from the absence of comment from the entourage, Scheijen concludes that nobody had any notion of the anxiety Diaghilev suffered. He finds the silence about Valentin mystifying and suggests that the Russians may have been afraid to talk lest Valentin’s family (and their own families?) suffer reprisals. But then he undercuts this sensible speculation by adverting to Diaghilev’s personal vanity and how he had a psychological need to maintain a façade of august imperturbability. Under these trying circumstances—Paris was seething with rumors and Cheka spies were everywhere—Scheijen’s attempts to make an issue of whether Diaghilev’s politics were tsarist or Bolshevist dissolve into the larger issue of his concern for the safety of his two half-brothers, both of them White Army officers. (Valentin was shot a few weeks after Diaghilev died. Yuri had been deported to Central Asia in the late Twenties.)

It follows from Scheijen’s restricted view of modernism that there are blanks at the end of his book where the Ballets Russes’ final triumphs should be. The parade of witnesses has thinned out, and Scheijen is left to build his case from scraps. Diaghilev’s previous biographers have tried to explain his withdrawal from company affairs in the last years of his life, citing fatigue, ill health, melancholia, boredom, or the distraction of his rare book collection. Scheijen denies that Diaghilev withdrew and insists that his enthusiasm was as great as ever. His version of the years 1927–1929 seems aimed directly at Buckle, who labeled the whole decade “The Kochno Period.” This awarded too much credit to Boris Kochno, Diaghilev’s lieutenant and Buckle’s main source of information. Scheijen veers in the opposite direction and refuses Kochno any recognition except for some of the librettos he signed. Kochno had in fact acquired more power, but not enough to account for the sudden change in direction that overtook the last five years of the Ballets Russes and made them as rich as the first five.

This change, barely noticed by Buckle, unmentioned by Scheijen, brought a whole new spiritual depth and commitment to such ballets as Ode, Apollo, and The Prodigal Son. Who or what was responsible for it? “France, like many other countries at the time, was in the grip of new spiritual movements and religious fads, but,” Scheijen assures us, “Diaghilev was immune to them.” Stravinsky’s return to Orthodoxy? That had occurred in 1926, leaving no impression on Diaghilev. (Scheijen forgets to remind us that Diaghilev and Stravinsky had once planned a ballet based on the life of Jesus.) In his youth, Diaghilev had had a Tolstoyan period, probably under the influence of Filosofov, who became a religious philosopher. Scheijen recounts their reunion in 1928, which only confirmed that they had nothing in common. That sounds right; Diaghilev’s religion was art. And in his fifties he was undergoing a conversion of his own, to that very neoclassicism that Scheijen has been at pains to scorn.

The persistence of rearguard resistance in the press had made it necessary yet again for Diaghilev to refute the claims of old ballets and dead forms. His statement, uncovered by Russian researchers in 1982, marks a change in his attitude toward choreography, a change coincident with the momentous development in Ballets Russes idealism. Diaghilev begins by mentioning his debt to “Duncan and Dalcroze and Laban and Wigman” and goes on to draw a different picture of modernism. (Notice that he sees New York in the picture.)

The creators of the marvellous American skyscrapers could easily have turned their hands to the Venus of Milo since they had received a complete classical education. But if anything does offend our eye in New York, it’s the Greek porticos of the Carnegie Library and the Doric columns of the railway stations. The skyscrapers have their own kind of classicism, i.e. our kind. Their lines, scale, proportions are the formula of our classical achievements, they are the true palaces of the modern age. It’s the same with choreography. Our plastic and dynamic structure must have the same foundation as the classical work which enables us to see new forms. It too has to be well proportioned and harmonious, but that doesn’t mean propounding a compulsory “cult” of classicism in the creative work of the modern choreographer. Classicism is a means, not an end.

That was uttered in 1928, the year of the Stravinsky-Balanchine ballet Apollo. It wasn’t altogether a new idea; Diaghilev had expressed much the same sentiment at the age of thirty, when he argued against the reconstruction of the Campanile in Venice, after its collapse in 1902. His gift for reconciling contradictions, strengthened by years in the business of marketing high art, may very well have attracted him to the old-new paradoxical nature of neoclassicism. And he had before him the supreme example of Apollo, which broke decisively with the past by reimagining it.

Diaghilev didn’t get to commission Apollo, and because he resented Stravinsky’s independence Scheijen thinks that he wasn’t much interested in the ballet. Scheijen isn’t interested in it either; his treatment of the premiere is cursory to the point of indifference. Compare Sacre, which Diaghilev initially also resented because Stravinsky and Roerich had worked it up between themselves without his knowledge. Whereas Sacre has Scheijen’s full attention, when it comes to Apollo he can only bring up another scandal, and even on that he has almost nothing to say. A few months after the premiere season, Diaghilev cut Terpsichore’s variation. Stravinsky was so upset that he filed suit. What caused Diaghilev to delete a sublime variation from Apollo, a ballet he professed to adore, is a complex question that Scheijen doesn’t confront. Could it have had something to do with Serge Lifar, whom Diaghilev adored even more and whose variation followed immediately after Terpsichore’s? Scheijen blames the off-and-on feud with Stravinsky and puts the vandalism down to sheer petulance.

Diaghilev’s exaggerated fears of disease and death, often dismissed as superstitions by memoirists, were based on serious afflictions and were with him a long time. As a student, he met Leo Tolstoy and afterward wrote him long, troubled letters about sexuality and death, to which Tolstoy is said to have replied. The most heartfelt letter, which Sergei wrote on his twenty-first birthday, is excerpted by Scheijen in the V&A album, evidently having come to light after his book was published. The intensity of this experience with Tolstoy, the urgency of his need for the fatherly, not to say godly, figure of Tolstoy (his own father was aloof), cannot fail to have had an effect on Diaghilev’s moral character. In later life, it’s true that he was superstitious rather than religious, unlike Stravinsky, who was superstitious and religious. But though Diaghilev lacked religious belief he did not lack religious feeling. When Stravinsky asked for his charitable forgiveness in order to take communion, he wrote back:

I think only God can forgive because only He can judge. When we quarrel and when we repent we, poor little lost souls, must have enough strength to greet one another as brothers and to forget all that wants forgiveness. If I want it, it’s because it concerns me too, and although I am not preparing for communion I still ask you to forgive me all my conscious and unconscious sins towards you and only to keep in your heart that feeling of brotherly love I feel for you.

One would have to side with his most militantly malicious enemies not to think that he was sincere.

If the religion of art can be said to have had saints, Sergei Diaghilev was one. His whole enterprise had about it the odor of sanctity. When he could not pay his creditors or his dancers or his own hotel bills, he ate in truckers’ cafés and closed his astrakhan coat with a safety pin. A diabetic, he was also plagued with boils. His dancers who could not afford to buy clothes wore their costumes. From the beginning, he considered himself and all who joined him bound by the ethic of hard work. “You can’t imagine what it’s like, the Ballets Russes,” Matisse wrote to his wife. “There’s absolutely no fooling around here—it’s an organisation where no one thinks of anything but his or her work—I’d never have guessed this is how it would be.”

Diaghilev died in 1929, bringing to a sudden end what I would prefer to call the foremost theatrical adventure of the first half of the twentieth century. (The second half was dominated by the New York City Ballet.) Scheijen’s biography came out in the Netherlands in 2009, marking the hundredth anniversary of the Ballets Russes and the eightieth of Diaghilev’s death. The English edition is shoddy. Haste, either on the author’s part or the publisher’s, seems to have eliminated the reasons for calling Nouvel “that eternal mischief-maker,” Benois “the group’s moral conscience” (moral in what way?), Cocteau “Stravinsky[‘s] enemy,” and the Prince’s Theatre in London “ill-starred.” Careless editing may have created the abysmal gaps for which I have faulted Scheijen’s detection; time and again clues are planted, then abandoned. Textual errors include naming Aschenbach the protagonist of Thomas Mann’s “eponymous novella.” Yakulov, the scenic designer of Le Pas d’Acier, was Georgy, not Grigory. The Prodigal Son is not carried offstage by his father. Making the illustrations mostly drawings of Ballets Russes personnel by other Ballets Russes personnel was a bad idea, particularly in light of the book’s potential appeal to newcomers: if you don’t know what Léon Bakst looked like, Picasso’s savage caricature won’t tell you much. As if to compensate, eight color photographs of ballets and ballet designs of little or no relevance to the text are inserted.

To all of this the V&A’s Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes is the perfect antidote. Visually luxurious, the volume has been impeccably edited by Jane Pritchard, the curator of the V&A dance collection who also curated the show, along with Geoffrey Marsh. Every aspect of the Ballets Russes is covered, either in brief notes or in extended critical articles by such authorities as the art historian John E. Bowlt and the musicologist Howard Goodall. Pritchard applies her customary expertise to a range of subjects, including ballet in London before Diaghilev, the various sources and talents on which Diaghilev drew for his productions, and his legacy. Sarah Woodcock’s excellent piece on costumes reminds us of the price all too frequently paid by the dancers for visual sensations created by the painters. Heavy, cumbersome costumes, wigs, and hats impeded movement and stifled breathing.

Dancing in The Rite of Spring was always a disagreeable experience—Nijinsky’s energetic choreography, the wool and flannel costumes, so many dancers packed together on stage, sweating with exertion, excitement and fear, generated heat like a furnace. Adding to the unpleasantness was the overpowering smell of hot, damp wool.

In her essay on the Diaghilev legacy, Pritchard enumerates the many previous Ballets Russes exhibitions that, to judge from the sheer weight of information packed into this album, the current show quite overshadows. The old nostalgic celebrations are being reactivated in a kind of vacuumatic perfection, and with an abundance of detail that might have been unnerving only fifteen years ago but that is entirely apposite to our era of technological omniscience and aesthetic vacancy.

This Issue

January 13, 2011