The exhibition on Jan Gossart organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery, London, celebrates a Netherlandish painter of the early sixteenth century who is little known except by historians, yet deserves wider attention. He not only introduced a new appreciation of classicism to the art of northern Europe, thereby bringing it closer to the concerns and achievements of the Italian Renaissance, but he produced remarkably beautiful and complex portraits and mythological and biblical paintings.

Gossart was one of the first northern painters to travel to Rome to study, and possibly the first Netherlandish artist to make paintings of mythological subjects, populated with figures whose anatomy and poses show the influence of classical and Italian art. Entitled “Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart’s Renaissance,” the exhibition emphasizes the painter’s interest in secular narratives, voluptuous nudes, and the sculptural three-dimensionality of his figures.

As a young man Gossart went to Rome in 1508–1509 in the entourage of Philip of Burgundy, the illegitimate son of Philip the Good, who was there to negotiate with Pope Julius II on behalf of Margaret of Austria, the regent of the Netherlands. Gossart spent about seven months in Rome, and although only a few drawings from the trip survive, they show the enormous change he underwent there. His pictures from before this time were rendered in a fussy and picayune manner; they are airless and cluttered with ornate detail. Even when depicting classical subjects, such as The Emperor Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl, they have the look of late Gothic manuscript illuminations, and show no knowledge of Greco-Roman culture.

The drawings he made in Rome, some at Philip’s request, are completely different in character. One depicts the Colosseum; another three are studies of classical sculpture. In what might be the earliest of his Roman drawings to survive, he copied the famous bronze statue called the Spinario, of a boy removing a thorn from his foot. In this study Gossart’s line is hesitant and the depiction of form and shadow unsure, with the result that the sculpture looks lumpy and misshapen. But in another, presumably later, drawing he made in Rome, based on the statue called Apollo Citharoedus (showing Apollo playing a lyre), he described the details of the anatomy with delicate webs of fine lines, carefully rendering light and shade as they fall across the statue. The mastery of technique and the glow of inspiration are apparent in this beautiful sheet, as well as in the study he drew of the colossal bronze Hercules of the Forum Boarium.

Upon his return to the Netherlands in 1509, Gossart lived in Middelburg, a town near Philip’s castle in Souburg (and not too far from Bruges and Antwerp). His paintings of the next few years do not always bear strong evidence of his time in Italy; rather he worked in a style deeply indebted to the fifteenth-century painters Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling, and he sometimes even collaborated with Gerard David, the most direct heir of this tradition. Many of Gossart’s paintings of this period, such as the Malvagna Triptych, are images of the Virgin and Child, seen enthroned in architectural settings of jewel-like splendor. Despite the trip to Rome, the style of the buildings is still Gothic, although there is a new amplitude in the depiction of space, no doubt partly owing to his study of Italian pictures, such as Mantegna’s San Zeno Altarpiece, which Gossart had seen on a stop in Verona.

The turn to pagan subjects and classical figure style came only in 1515 when Philip of Burgundy commissioned Gossart, together with the Venetian artist Jacopo de’ Barbari, to paint mythological nudes for his castle. Philip was one of the first princes in northern Europe to aspire to be a humanist ruler; he had read Vitruvius, and corresponded occasionally with Erasmus. But Philip’s interest in images of this kind also surely arose from his legendary lust for life. His secretary and biographer Gerard Geldenhouwer records that Philip was “rather inclined to physical love” and “passionate in the love of young girls.” This passion remained unchecked even after he was made bishop of Utrecht in 1517.

The show unfortunately does not include Gossart’s two largest surviving mythological pictures, the Danae (now in the Alte Pinakotek, Munich) and the Neptune and Amphitrite (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). But it does have a group of smaller paintings and drawings, of which the most beautiful is an elegant Venus and Cupid. The voluptuous body of the goddess is pale and full like that of a Hellenistic statue, and her gracefully spiraling pose ultimately comes from Raphael. (Although perhaps Gossart knew this pose in a print by Marcantonio Raimondi or in a boxwood statuette by Conrad Meit, which are exhibited near the picture.)

Advertisement

Yet for all their obvious allure and importance, I do not find the mythological paintings to be the most engaging pictures in the show. Whenever Gossart represents beings of absolute sublimity, whether they are the heavenly Virgin and Child or the Olympian Venus and Cupid, there is a remoteness and coolness in their characterization. Their perfection is beyond the realm of human struggle and emotion. Looking at such figures it is very difficult to see what, if anything, they are thinking or feeling.

Gossart strikes me as a more successful artist when he is contemplating and depicting figures on earth rather than from the sky. Especially remarkable are his psychologically complex and affecting pictures of Adam and Eve. In one of the earliest of these, on a wing of the Malvagna Triptych, they are shown in the last moment of prelapsarian happiness and communion. Adam wraps his right arm around Eve’s shoulders, his right hand hanging down to her right breast. It is a convincing image of a loving and united couple. But with his left—sinister—hand, Adam is reaching out to take the apple from the mouth of the snake in the tree before them. The downfall has arrived.

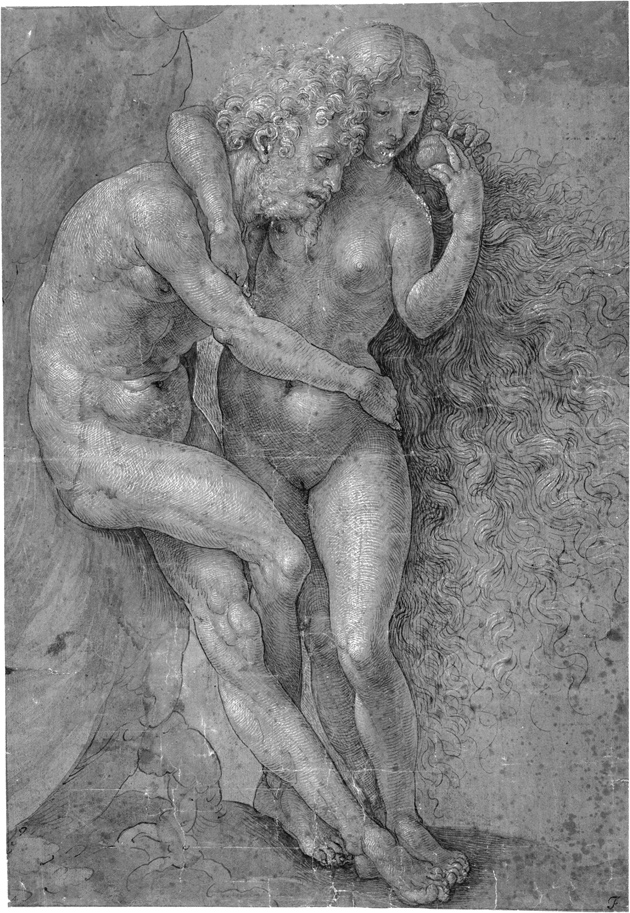

The drawings of Adam and Eve are still more powerful. In a sheet from Chatsworth, Gossart again shows them tightly bound together, and again emphasizes that sexual love is part of their bond. The glow of her left breast, the swell of her belly and pudenda, and the exuberant cascade of her luscious curly hair give her an astonishing physicality; and with a hand around her hip, Adam tugs her to his side. But this is not an image of bliss. Far from it. Their faces look haunted, haggard, ill, as if they have just endured a terrible ordeal. Though Eve is still holding the apple unbitten in her left hand, the picture seems to show them after the expulsion from Paradise.

Likewise, in another drawing of the subject, the characterization of the figures is complex and contradictory. As the catalog notes, this sheet in the Albertina, Vienna, “projects the couple’s intimacy, intermingled with shame and guilt.” None of Gossart’s mythological pictures is so sensitive in its depiction of emotion.

Gossart’s extraordinary powers of observation are especially telling in his portraits. The show concludes with a room of twenty or so of these pictures and they make a strong impression. In the history of portraiture in the north, Gossart comes between Hans Memling and Hans Holbein the Younger: his pictures have something of Memling’s immediacy and Holbein’s depth.

The portrait of the powerful Flemish cleric and statesman Jean Carondelet is one of the greatest pictures in the exhibition. On the left half of this diptych you see Carondelet at prayer; on the right side are the Virgin and Child, the objects of his veneration. Carondelet is shown in tight close-up: you see just his head and hands; the Virgin and Child are viewed from slightly more afar. Soft warm light falls across Carondelet’s face, which Gossart has depicted with painstaking detail. You can, for instance, count his eyelashes, or see the window of the room where he is seated reflected in the blue of his irises. But this image not only portrays Carondelet’s physical appearance; it is also represents his character. The look on his face is one of resolve and hope. The paintings on the back of the diptych—a broken skull and the Carondelet coat of arms—and the five inscriptions surrounding the pictures spell out that this portrait is meant to show his commitment to virtue and duty even in the face of death. Carondelet was a good friend of Erasmus and a chief adviser to Charles V. Looking at his picture you can imagine why he earned their trust.

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know