Hiroyuki Nagaoka/Getty Images

Buddhist prayer flags at the base of Mount Kailas in Tibet, where pilgrims come to walk the perimeter of the mountain, and where some monks and nomads follow the practice of sky burial. ‘Especially in this propitious month of Saga Dawa,’ Colin Thubron writes, ‘people may repair to lie down and enact their own passing.’

Mount Kailas in Tibet is the epicenter of the universe for one fifth of humankind. To Hindus and Buddhists it is the source of life itself, created by cosmic waters and the mind of God, and blessed by the Buddha, who flew here with five hundred disciples. From its foot flow the four rivers that nourish the world, and in sacred scripture everything created—trees, rocks, humans—finds its blueprint here.

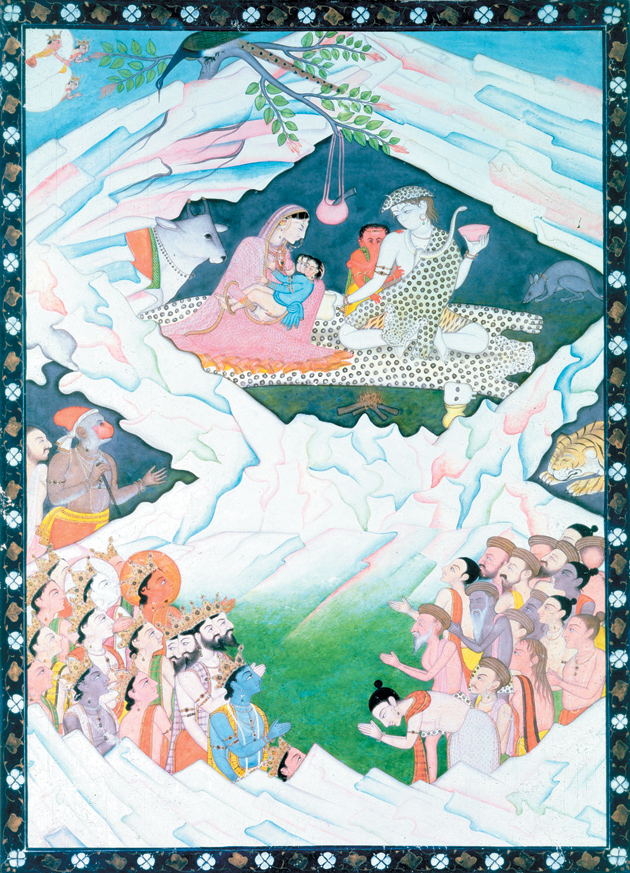

Geography has strangely reinforced this. Early wanderers to the source of the four great Indian rivers—the Indus, Ganges, Sutlej, and Brahmaputra—found that each one rose near a cardinal point of Mount Kailas. Situated in Ngari, the coldest and most sterile region of Tibet, the mountain has become synonymous with the remote and forbidden. It was already old in sanctity when Buddhism entered the country in the seventh century. Hindus believe its summit to be the palace of Shiva—lord of destruction and change—who sits there in eternal meditation.

But it is unknown when the first pilgrims came. Buddhist herders and Indian ascetics must have ritually circled the mountain for centuries, and the blessings accruing to them increased marvelously in sacred lore, until it was claimed that a single circuit expunged the sins of a lifetime. The mountain was dangerous to reach, but never quite inaccessible. Only in the nineteenth century did Tibet itself become a forbidden land. And Kailas kept its own taboos. Its slopes are sacrosanct, and it has never been climbed.

But in recent years it has been protected less by sanctity than by political intolerance. In 1962, four years before the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese banned all pilgrimage here (although devotees still circled it secretly) and only in 1981 were the first Tibetans and Indians permitted to return. Twelve years later a few hikers were tentatively allowed to cross the mountain borders between Nepal and Tibet.

My own small journey follows these. But the Chinese suspicion of lone travelers has compelled me to join a group of seven British trekkers on the Nepalese border—we separate at the foot of Kailas—for the charade of not entering Tibet alone. To this remotest province access has always been hard, and police have constricted it further. It is over a year since the pre-Olympics riots in Lhasa, but in this Buddhist holy month of Saga Dawa, Beijing’s distrust of gatherings is running high. On the eve of the full moon, they fear a huge congregation under the mountain.

I reach it with two sherpas, climbing along the Karnali River from Nepal. The mountain lies barely sixty miles beyond the border. An espalier of linked prayer flags has converted the valley beneath its western face to a vast, open-ended oval of dripping color. At its center an eighty-foot pole—three or four pine trees clamped end to end—hovers stupendously aslant, waiting to be raised ceremonially tomorrow, and around it the crowds are already circling clockwise, several hundred people, chanting.

But apprehension is in the air. The trucks of the Chinese police and army have penetrated along the valley—they are lined up opposite us—and every twenty yards, in a cordon around the pole, a soldier is standing stolidly at attention. The police are sealing off an overhanging hillock, and squads of soldiers, wielding batons and riot shields, are stamping back and forth, their march an open threat. But beyond the palisade of flags the pilgrims camp oblivious among boulders, picnicking or praying. Traders have set up shop in tents, and a Chinese mobile clinic is processing people for swine flu.

The only building is a stone hut. Cramped into its dimness, seated at low tables, some twenty monks are chanting and playing instruments. The noise is terrific. They are robed in a medley of crimson, maroon, and mustard yellow, and they span all ages. The emblazoned hats of the senior monks taper up like cherry-red miters while the juniors’ flare into pharaonic crowns that overhang their faces a foot above. They motion me to sit with them. Their tables are littered with butter lamps, bells, bottles of cola, and the stiff leaves of sutras. Aligned in worship, they form a genial gallery of whiskered age and callow youth. Pilgrims crowd in, touching money to their foreheads before they leave it for the monks. A novice collects the notes in a box labeled Budweiser, while another ducks among the chanting heads to serve them bowls of coagulated rice and radishes, which they eat with jovial slurping while they pray. And all the time the unearthly music continues, with its voices like insects stirring, the horns braying their melancholy, the tap of a curved stick on an upright drum, and the watery explosion of cymbals.

Advertisement

It was this Red Hat Kayuga sect, in the twelfth century, that instigated around Kailas the practice of sky burial. Perhaps, as some say, Tibetan culture is death-haunted. Certainly its death cults haunt others. When I escape from the clamor of the monk-filled hut, I see, above the ground where the enormous pole will rise tomorrow, an empty plateau, called Drachom Ngagye Durtro, against the valley wall. On this durtro, or charnel ground, the sky burial of monks and nomads continues. The remorseless Demchog, the Buddhist demigod who dances out on Kailas the promise and terror of dissolution, imbues this durtro with an ambivalent power. Like Shiva, whose ash-blue skin and skull garlands he shares, Demchog is lord of the charnel house, and his followers in the past have inhabited cremation grounds (they occasionally still do) to meditate on the impermanence of life and achieve the truth of emptiness. It is to such places, especially in this propitious month of Saga Dawa, that people may repair to lie down and enact their own passing. So the durtros become sites of liberation. Rainbows are said to link them to the eight holiest cremation grounds of India, whose power is mystically transmitted to Tibet.

A land of frozen earth, almost treeless, can barely absorb its dead. Holy law confines to burial only the plague-dead and the criminal: to seal them underground is to prevent their reincarnation, and to eliminate their kind forever. The corpses tipped into Tibet’s rivers are those solely of the destitute. Embalmment is granted to the highest lamas alone, while the less grand are cremated and their ashes encased in mounds of mud or clay called stupas.

For the rest, the way is sky burial. For three days after clinical death, the soul still roams the body, which is treated tenderly, washed by monks in scented water, and wrapped in a white shroud. A lama reads to it The Liberation by Hearing, known in the West as The Tibetan Book of the Dead, by which the soul is steered toward a higher incarnation. An astrologer appoints the time of its leaving. Then, before the corpse can decay, its back is broken and it is folded into a fetal bundle. Sometimes this sad packet—surprisingly small—is carried by a friend to the sky burial site; sometimes it is laid on a palanquin and preceded by a retinue of monks, the last man trailing a scarf behind him to signal to the dead the way they are going.

As the corpse approaches, the sky master blows his horn, and a fire of juniper twigs summons the vultures. The master and his rogyapa—corpse dissectors—then open the body from the back. They remove the organs, amputate the limbs, and cut the flesh into small pieces that they lay nearby. The bones are pulverized with a rock. The master mixes their dust with barley or yak butter, then rolls it into balls. Finally the skull too is smashed and becomes a morsel with its brains. One by one these are tossed onto a platform—the bones first, for they are the least appetizing—and the vultures crowd in.

These birds are sacred, thought to be emanations of white dakinis, the peaceful sky dancers who inhabit the place. Their foreknowledge of a meal is uncanny. The submission of a corpse to them is the last charity of its owner, and lightens the karma of the dead. The birds themselves are never seen to pollute the earth. They defecate in the sky. Tibetans say that even in death they keep flying upward until the sun and wind take them apart.

As I climb to the durtro plateau it shows no sign of life. A healing spring flows near its foot, and a white segment of Kailas shines above. My path winds up into light-blown dust. The sun is dipping as the way levels into an aerial desolation. It is scattered with rocks that may be the remains of rude memorials, makeshift altars, or of nothing. An icy wind is raking across it. The slabs for dissection are merely platforms, smoothed from the reddish stone and carved with mantras. People have left hair and clothing here, even teeth and fingernails, like hostages or assents to their death. I see a woman’s silk waistcoat, and a child’s toy. A palanquin lies abandoned. And now the wind is wrenching at all ephemera and bundling it away—faded garments, old vulture feathers, tresses of hair—to decay at last under rock shelves.

Advertisement

For a while I see nobody but an old couple wandering the perimeter. They move as if blind, huddled against the cold. Then I become aware of a man lying prostrate fifty yards away. As I look he gets to his feet and hurls handfuls of roasted barley into the wind, crying out. I make out a young face, circled in black locks. The wind stifles his words. He seems to be praying not to Kailas—his back is turned to it—but to the cemetery itself. Perhaps he is addressing the dakinis, but more likely invoking the Gompos, the Dark Lords, who inhabit all cemeteries. The followers of these Gompos are the dregs of the spirit world: the hungry ghosts, the flesh-eaters, the rolang undead. By the rite of chodpa the yogi invites them to devour his ego, hurrying him to salvation. And suddenly the man’s barley has finished and he is rolling in the dust. His hair spins about him. He makes no sound. This is no pious grovel but a headlong rotation over the ground, inhaling the dead. Then he lies still.

After he leaves, I go over to the terrace where he had been. Among the boulders I see two long, wide-bladed knives, then the ashes of a fire where a charred hacksaw lies. Then I come with alarm to the center of the platform. A wooden board is there, scarred by blades. There are other knives, quite new, and an ax. They seem to have been discarded. And beneath the board, two bones are lying together—the arm bones of a human—with dried blood and flesh still on them.

I feel a wrenching revulsion, and a shamed excitement at the forbidden. I had heard that sky masters were artists of their kind, heirs to a strict profession. To leave one human piece uneaten will invite demons into the body: they will reanimate it as a rolang, a living corpse, and steal its spirit.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library

The holy family of Shiva and Parvati on Mount Kailas; eighteenth-century Indian school painting. According to Colin Thubron, ‘Hindus believe its summit to be the palace of Shiva—lord of destruction and change—who sits there in eternal meditation.’

But everything on the durtro betrays crude carelessness. Perhaps its sky master has grown bitter. Like butchers and blacksmiths, the stench of uncleanness clings to the rogyapas. Called “black bones,” they are shunned in their community. If they should eat in your home, their plate is thrown away. Their daughters rarely marry. Sometimes, too, their rules are transgressed. Tantric yogis even now, seeking stuff by which to brood on death, find human thigh bones for their trumpets, and skulls are offered them as ritual cups.

I cross the plateau in numb recoil. I glimpse pilgrims’ fires on the slopes below, and start to go down. Only a belief in reincarnation might alleviate this bleak dismay. Without it, the once-incarnate dead become uniquely precious, and break the heart.

At sky burials the grief of relatives is said to disrupt the passage of the soul, and sometimes none attend. Instead a monk is sent in advance to the cemetery, to ask its spirits to comfort the corpse as its body is dismembered. But generally the mourners come: it is important, they may think, to confront evanescence, and witness liberation. At some funerals, so onlookers claim, the mourners display no sorrow. They have learned the lesson of impermanence, and look with equanimity at the passing of the appearances they know.

But others say they lie on the ground, weeping.

The pilgrims circling the flagpole in the valley might be mimicking the greater circuit of Kailas, which many will perform tomorrow. They must ritually keep sacred objects on their right, so they orbit clockwise from early morning, in an aura of triumph. Viewed from the hillock where I stand, this seems an act not only of faith but of possession, as tigers mark out their territory at night, and I have the notion that Tibetans, by repeated holy circuits—of mountains, monasteries, temples—are unconsciously reclaiming their sacred land.

Whether in the ritual of pilgrimage, the cycles of reincarnation, or the revolution of the Buddhist Wheel, the circle is here the shape of the sacred. In folklore, gods, demons, and even reptiles perform the pilgrimage. By this dignity of walking (and in Tibetan speech a human may be an “erect goer” or “the precious going one”) pilgrims acquire future merit and earthly happiness, and sometimes whole families pour around Kailas with their herds and dogs—all sentient creatures will accrue merit—after traveling here for hundreds of miles.

As the morning wears on, the crowds thicken. A thousand pilgrims there may be, wheeling around the pole like planets around a sun. They go fast, buoyantly, as if on pious holiday. In this biting air, sheepskin coats still dangle from their shoulders in ground-trailing sleeves; the earflaps fly free from women’s multicolored bonnets, and the men’s shaggy or cowhand hats are tilted at any angle. Sometimes, in ragged age, the people prod their way forward with sticks, their prayer wheels spinning. Among them the tribal nomads march in a multicolored flood. All that the women have seems on display, and a playful courtship is in the air. Their belts are embossed silver and seamed with cowrie shells, and sometimes dangle amulets or bells. They are bold and laughing. Necklaces of amber and coral cluster at their throats, and their brows are crossed by turquoise-studded headbands, their waists gorgeously sashed. There are groups of local Dropka herdspeople, and hardy Khampas from the east, whose hair is twined with crimson cloth. And here and there gleam fantastical silk jackets—pink, purple, and gold, embroidered with dragons or flowers.

Ringed by Chinese soldiers, the flagpole stays monstrously aslant, dripping with prayer flags, waiting. The celebratory pennons fly everywhere in colors too synthetic for the elements they symbolize: earth, water, air, fire, space. Examining them, I recognize only Padmasambhava, Tibet’s foremost saint, stamped in woodblock, and the sacred wind horse, saddled with holy fire. On the outmost perimeter other prayers hang in faded waterfalls, printed on white cloth twice the height of a man. Bundled into diaphanous swags, they fall massed and unreadable, like folded books. But every year they are assembled here, their draped forms fidgeting like ghosts in the wind, to bestow the protection of their sutras, the magic of words.

On a hillock above, the police scan the valley through binoculars, and officers are coordinating patrols through a walkie-talkie. Their telescopic video camera whirs on a tripod, waiting to record troublemakers. The soldiers remain at attention in their cordon around the pole and their posses—swinging truncheons and riot shields—swagger counterclockwise against the pilgrims or stand in squads of five or six beyond the hanging prayers. But the Tibetans look straight through them, as if they had no meaning. All morning a helmeted Chinese fire officer stands alone and rigid, fulfilling some regulation, with a canister on either side of him, and nothing flammable in sight.

The northern clouds have thinned away, and the tip of Kailas rises beyond the charnel ground. A few pilgrims are facing it now, lifting their joined hands to their foreheads. They call the mountain not the Sanskrit Kailas but Kang Rinpoche, “the Precious One of Snow.” They may imagine on its crest the palace of Demchog, but even this Buddhist demigod cannot quite dispel a sense of ancient and impersonal sanctity, as if the mountain’s power were inherently its own. This is the stuff of magic. In the eyes of the faithful its mana is intensified wondrously through all those who have meditated here, so that the kora—the pilgrimage itself—is rife with their strength. A single mountain circuit, it is said, if walked in piety, will dispel the defilement of a lifetime, and bring requital for the murder of even a lama or a parent, while 108 such koras lift the pilgrim into Buddhahood.

These mathematics weigh the mountain’s magic against the pilgrims’ spirit. In the past the rich might pay a proxy to undertake the circuit, the virtue dividing between them; and even now, if a pilgrim rides a yak or pony, half the merit goes to the beast. Both yak and human are subject to earthly contamination, drib, which like a stain or shadow accumulates alongside outright sins. Pilgrimage cleanses these. The way of tantric meditation, which dismantles the illusions of difference, is only for the few, and those around me, slowed now to gaze at the raising of the pole, will rack up merit by an earthier journey tomorrow.

A century ago the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, the first Westerner to join the pilgrimage, wrote that its people’s motives were simple. They hoped, in a future life, to be allowed to sit near Demchog; but they had other, more material concerns. Even now the remote workings of karma fade before the day-to-day. The pilgrim prays for disease to leave his cattle, for a higher price for his butter, for luck in sex or gambling. She wants a radio, and a child. Such matters belong to the buddhas and tutelary spirits of a place. In the lonely hermitages, the gompas, around Kailas, they will offer the spirits incense to smell, a little rice to eat, a bowl of pure water. And somewhere in these wilds they may whisper to the fierce mountain gods to bring the Dalai Lama back to Lhasa, and drive the Chinese out.

A slight, saffron-clad figure stands before the flagpole. Tiny and quaint under a tasseled crimson hat, he is the master of ceremonies, piping orders through a megaphone. Two hefty gangs, thirty strong each, start heaving on long ropes attached high up the mast, while a pair of trucks, their front bumpers bound to it by cables, go slowly into reverse. A shout of expectation goes up, and paper prayers are hurled into the wind. The pole begins to lurch upward. The rods that have supported it aslant drop away, and its strands of tethered prayer flags are dragged upward in harlequin arcs.

Then the pole judders to a stop, hanging at a forty-five-degree diagonal, like a barrel pointing at Kailas. The spectators are shouting in a tense half-chant, their hands clasped together. The master of ceremonies runs from side to side, guiding the rope gangs. If the pole does not slot bolt upright in its socket of stones, ill luck will befall Tibet for the coming year. For two decades until 1981 the ceremony was banned, while the country suffered. And now the guy ropes are taut and equal, the saffron figure shouts, and the pole glides upward until all support is gone. The carnival streamers unfurl like petals around it, and the great tree stands miraculously upright, held only by these frail garlands of color.

The sky-blue silk at its summit, by design or chance, slips down to reveal the golden orb that crowns it, and the crowd bursts into triumphant cries of Lha-gyel-lo-so-so! Lha-so-so! Lha-so-so! Victory to the gods! They shower fistfuls of barley into the air, over and over, exploding it in pale clouds toward the mountain. They delve into bags brimming with prayer leaves, which soon become a snowstorm. A ceremonial oven, built of clay brick and stoked with yak dung and juniper, becomes a repository for more thrown prayers and incense sticks, until the air fills with a dense, white blossom of benediction—scent, blown barley, paper—that falls around the boots of the Chinese soldiers, still impassively at attention, and floats on like mist toward Kailas.

The monks, who have been praying in a seated line for hours, advance in a consecrating procession. Led by the abbot of Gyangdrak monastery from a valley under Kailas, they move in shambling pomp, puffing horns and conch shells, clashing cymbals. Small and benign in his thin-rimmed spectacles, the abbot holds up sticks of smoldering incense, while behind him the saffron banners fall in tiers of folded silk, like softly collapsed pagodas. Behind these again the ten-foot horns, too heavy to be carried by one monk, move stertorously forward, their bell flares attached by cords to the man in front. Other monks, shouldering big drums painted furiously with dragons, follow in a jostle of wizardish red hats, while a venerable elder brings up the rear, cradling a silver tray of utensils and a bottle of Pepsi-Cola.

But by late afternoon, with the ceremonies over, the wheeling crowds have thinned away. All around the perimeter they have looped the circling flags inward to the pole, so that you clamber through a jungle of vivid creepers, snagging underfoot or slung close above you. By dusk the pilgrims have dispersed to their campgrounds, and the place is silent. Now it seems to sag in brilliant ruin, like some game abandoned by children at evening. Its remembered rite carries with it, in spite of everything, a charge of innocent optimism, of earthy piety and trust. In the twilight a few campfires start up around the valley, and a faint perfume lingers: incense lit to feed the unhappy dead, and to please the darkening mountain.

Few beliefs are older than the notion that heaven and earth were once conjoined, and that gods and men moved up and down a celestial ladder—or a rope or vine—and mingled at ease. Some primeval disaster severed this conduit forever, but it is remembered all through Asia and beyond in the devotion to ritual poles and ladders: the tree by which the Brahmin priest climbs to make sacrifice, the stairs that carry shamans to the sky, even the tent pole of Mongoloid herdsmen, the “sky pillar” that becomes the focus of their worship. Such cults (tabulated assiduously by Mircea Eliade) rise from a vast, archaic hinterland, from the world pillars of early Egypt and Babylon, and the ascension mysteries of Mithras, to the heaven-reaching trees of ancient China and Germany, even to Jacob’s angel-traveled ladder that ascended from the center of the world.

These concepts, which spread in part from Mesopotamia, have in common that their life-giving stair or vine, by which sanctity replenishes the earth, exists at the world’s heart, the axis mundi; and in the sacred pole of Kailas, erected at the heart of the Hindu-Buddhist cosmos, they find a classic exemplar. Its raising was a timeless ceremony—intermittently performed—that marked the Buddha’s shallow victory over the Bon, the region’s primal faith. For the Bon, Kailas was itself a sky ladder, linking elysium to earth. The idea of a heaven-connecting rope is old in Tibetan belief, whose first kings descended from the sky by cords of light attached to their heads. By such ropes too it was thought the dead might climb to paradise.

Even in Buddhist myth there is something changing and fragile in the relationship between Kailas and its faithful. For all its mass, the mountain is light. In Tibetan folklore it flew here from another, unknown country—many of Tibet’s mountains fly—and was staked in place by prayer-banners and chains before devils could pull it underground. Then, to prevent the celestial gods from lifting it up and returning it to where it came from, the Buddha nailed it down with four of his footprints.

But now, they say, it is the age of Kaliyuga, of degeneration, and at any moment the mountain could fly away again.

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know