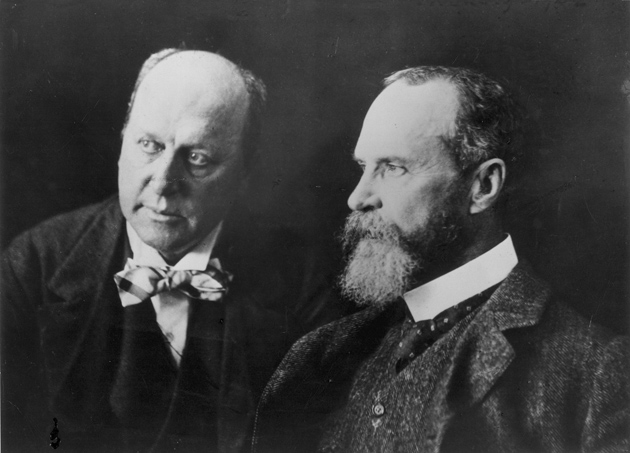

In the spring of 1870 William James was twenty-eight and at the lowest ebb of what was already a swift-flowing and emotionally tempestuous life. His early years had been spent trailing about Europe in the wake of his brilliant but improvident father Henry Sr., who was busily working his way through one of nineteenth-century America’s greatest inherited fortunes, while writing reams of unreadable, and unread, philosophical and religious maunderings.1 In London, Paris, Geneva, Berlin, young William and his brother Henry, the future novelist, had picked up bits and scraps of an education—precious bits, brilliant scraps—and, back home in America, William had attended Harvard Medical School and secured an MD, a thing far easier of achievement then than nowadays. He had tried his hand at being a painter and failed, had successfully avoided taking an active part in the Civil War—an evasion that haunted him all his life—had accompanied Louis Agassiz’s scientific expedition to Brazil, and had fallen in love with a bevy of girls, including his cousin, Minnie Temple. But Minnie died.2

We do not know enough about James’s inner life at this time to say for certain how profound an effect this loss had on the young man—and he was, even by his own admission, a very young twenty-eight—but in that fateful springtime, within weeks of Minnie’s death, he suffered a devastating emotional collapse that he was to describe years later in The Varieties of Religious Experience. The account, which he attributed to an anonymous French source, is vivid and frightening. Being in a state of depression and uncertainty about his prospects in life, he went one day at twilight into his dressing room

when suddenly there fell upon me without any warning, just as if it came out of the darkness, a horrible fear of my own existence. Simultaneously there arose in my mind the image of an epileptic patient whom I had seen in the asylum, a black-haired youth with greenish skin, entirely idiotic…. He sat there like a sort of sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes and looking absolutely non-human. This image and my fear entered into a species of combination with each other. That shape am I, I felt, potentially. Nothing that I possess can defend me against that fate, if the hour for it should strike for me as it struck for him.

After this glimpse into the horror rerum, James writes, “the universe was changed for me altogether” and he was left with “a sense of the insecurity of life that I never knew before, and that I have never felt since.” Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, he concluded by professing to believe that “this experience of melancholia of mine had a religious bearing.”

He was not the first in his family to be thus afflicted. Some twenty-six years earlier, in May 1844, when the James family was in residence in Windsor Great Park outside London, Henry James Sr. suffered a similar attack. At the end of a good meal, as he was sitting on contentedly at table after his wife and his two young sons had left, he suddenly became convinced that there was an invisible presence in the dining room with him, “raying out from his fetid personality influences fatal to life.” The effect was terrific: “The thing had not lasted ten seconds before I felt myself a wreck; that is, reduced from a state of firm, vigorous, joyful manhood to one of almost helpless infancy.”

For Henry Sr., as for his son, the event had a religious cast. Directed by a friend to the writings of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, of which he was to become a lifelong devotee, Henry discovered a name for what he had undergone. A vastation in Swedenborgian terms is a necessary purgative process through which the soul must pass on its way to enlightenment and spiritual rebirth. And indeed James père, leaning on the support of Swedenborg’s ecstatic vision, did find his way to the God of Love whose “great work was wrought not in the minds of individuals here and there, as my theology taught me, but in the very stuff of human nature itself….” It was a lesson that James fils strove valiantly all his life to put into practical effect, with more or less success.

William James is not universally admired. His pupil and friend George Santayana, though lovingly respectful of the master, could be ambivalent in his judgement. A more recent skeptic is Louis Menand,3 who in his fine book on the history of pragmatism, The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America, mocks the “man of two minds,” as he dubs James in a chapter heading, for being on the one hand a hopeless ditherer4 and on the other “a kind of super-Protestant,” overly concerned with the “cash-value” of experience, who “often spoke of pragmatism, the philosophy he largely created, as the equivalent of the Protestant Reformation.”5

Advertisement

True, there is a Benjamin Franklin, even a Teddy Roosevelt,6 side to James (although he strongly opposed Roosevelt’s imperialism) that at times grates somewhat. He does interrogate this or that philosophical conception by demanding “What is its cash-value, in terms of particular experience?” He is an enthusiast for the Weberian notion of the Protestant work ethic—but then, so was Marx—and he can be squirm- makingly the Great Outdoors, fresh-air-and-exercise man.7 Yet whatever heartiness he allowed himself to evince was hard-won, and, as Robert Richardson writes in his introduction to The Heart of William James, a splendid and shrewdly chosen selection from the philosopher’s work, “his self-help strain comes from his conviction that our thoughts have a shaping power over our bodies.”

James knew also the often destructive tendency of our thoughts, and the damage that the mind’s infirmities can inflict upon us. In the chapter from The Varieties of Religious Experience that he calls “The Sick Soul,” which Richardson reprints here, James faces squarely the awfulness of the human predicament: “Our civilization is founded on the shambles, and every individual existence goes out in a lonely spasm of helpless agony.” The Varieties is overall an affirmative and tolerant study of our need for and experience of transcendental states,8 but in “The Sick Soul” we have the impression of a man who has been plucked off the primrose path and set down in the inner circle of an earthly hell and forced to witness, white-knuckled and sweating, a parade of life’s most terrible torments. Healthy-mindedness is all very well, he writes, yet even the most fortunate must recognize that their happy state is the result of luck and not much else:

And then indeed the hollow security! What kind of a frame of things is it of which the best you can say is, “Thank God, it has let me off clear this time!” Is not its blessedness a fragile fiction? Is not your joy in it a very vulgar glee, not much unlike the snicker of any rogue at his success? If indeed it were all success, even on such terms as that!

“Can things whose end is always dust and disappointment be the real goods which our souls require?” James asks, and the question is not rhetorical. There is no doubt, he writes, that healthy-mindedness will not do as a philosophical doctrine, “because the evil facts which it refuses positively to account for are a genuine portion of reality; and they may after all be the best key to life’s significance, and possibly the only openers of our eyes to the deepest levels of truth.”

It is well to stress this blacker seam that runs through all of James’s radiant thought—though for the most part it is hard to discern because so finely stretched and deeply buried—for an awareness of it allows us to trust in the value of his more positive, more pragmatic urgings. Who better to direct us toward the light than one who knows the darkness intimately? As Richardson writes: “The father of Alcoholics Anonymous, Bill Wilson, credits James with the founding insight of that organization—that self-mastery comes only after self-surrender and an admission of hopelessness and helplessness.”

So fresh is William James’s thought and so unbuttoned and irreverent his character that he is always contemporary; it comes as something of a shock, therefore, to recall that he was born as long ago as 1842. He was a late starter, however, and did not publish his first proper book until 1890, when he was forty-eight. But what a book The Principles of Psychology was, and is. Two years after initial publication he brought out a more compact edition, Psychology: Briefer Course,9 the form in which the book is mostly read today. From it, Richardson takes the chapter on habit, which he rightly describes as a classic. Here James takes his lead from Sydney Smith, who in his wide-ranging and characteristically witty Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy wrote: “There is no degree of disguise or distortion which human nature may not be made to assume from habit.” Similarly, for James habit is

the enormous fly-wheel of society, its most precious conservative agent. It alone is what keeps us all within the bounds of ordinance, and saves the children of fortune from the envious uprisings of the poor. It alone prevents the hardest and most repulsive walks of life from being deserted by those brought up to tread therein…. It dooms us all to fight out the battle of life upon the lines of our nurture or our early choice, and to make the best of a pursuit that disagrees, because there is no other for which we are fitted, and it is too late to begin again.

And he closes the paragraph with the true if disenchanted observation that “it is well for the world that in most of us, by the age of thirty, the character has set like plaster, and will never soften again.”

Advertisement

Like his near contemporary Nietzsche, with whom he has certain fundamental traits in common, James as a philosopher was a determined anti-systematizer.10 His turn of mind was firmly democratic, and he delighted in positing everyday examples to illustrate the most abstruse hypotheses.11 “James’s writings,” Richardson writes, “are a standing rebuke to conventional thought, received ideas, professional jargon, classical education,” and it is for this reason, as much as for their insight and depth of focus, that they remain forever fresh. Can there ever have been as entertaining a philosopher as William James?

As Richardson points out, James was fortunate in his family and his teachers, but he was more fortunate still in his friends. These included Chauncey Wright, according to contemporary legend the brainiest man in Cambridge, Massachusetts,12 the proto-pragmatist Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Charles Saunders Peirce, whom James designated as the true founder of pragmatism—though Peirce preferred to call it “pragmaticism,” a word he considered too ugly to be kidnapped by the likes of James or John Dewey, both of whom he thought too lightweight. James had a fondness for all kinds of mavericks and oddities, of whom there was no lack in, for instance, the spiritualist circles in which he moved. One of his most stimulating, if strange, correspondents was the autodidact philosopher and mystic from upstate New York Benjamin Paul Blood. Richardson quotes a splendid passage from Blood’s Essays in Philosophy:

Certainty is the root of despair. The inevitable stales, while doubt and hope are sisters. Not unfortunately the universe is wild—game flavored as a hawk’s wing. Nature is miracle all. She knows no laws; the same returns not, save to bring the different. The slow round of the engraver’s lathe gains but the breadth of a hair, but the difference is distributed back over the whole curve, never an instant true—ever not quite.

The phrase “ever not quite” James took over from Blood as motto and talisman—“Ever not quite is fit to be pluralism’s heraldic device,”13 he declared, and pluralism, as we know, is at the foundation of pragmatism.

Pragmatism is the American philosophy, and a more original and far-reaching contribution to social thinking than those other two most influential strains of twentieth-century thought, logical positivism and linguistic philosophy,14 if only the rest of the world, and Europe in particular, would realize the fact. One of the things that makes pragmatism hard to accept among the older schools is its apparent fuzziness, a quality that Richard Rorty cheerfully accepted, indeed celebrated. It is far easier to act in the spirit of pragmatism than to describe what it is, but perhaps the most concise and elegant definition is given by the founder of conceptual pragmatism, C.I. Lewis:

Pragmatism could be characterized as the doctrine that all problems are at bottom problems of conduct, that all judgments are, implicitly, judgments of value, and that, as there can be ultimately no valid distinction of theoretical and practical, so there can be no final separation of questions of truth of any kind from questions of the justifiable ends of action.15

James would have put great store by the notion of the “justifiable ends of action.” Indeed, pragmatism is primarily a philosophy of action rather than speculation. We may, with Louis Menand, gently deplore James’s worldliness, his accountant’s way of totting up intellectual loose change, but he never let go of the conviction that a philosophy confined exclusively to the academy is a philosophy not worth pursuing. Practical results were his constant and prime concern. Some philosophers philosophize to philosophize, others philosophize to live. William James was firmly among the latter category.

Yet for a philosopher he was remarkably insistent on the questionable nature of so many of the concepts that European philosophy since Socrates had taken as fundamental and enduring. “Our whole cubic capacity is sensibly alive,” he wrote, “and each morsel of it contributes its pulsations of feeling, dim or sharp, pleasant, painful, or dubious, to that sense of personality that every one of us unfailingly carries with him.” However, in a later essay, “Does ‘Consciousness’ Exist?,” he seems to question the very concept of individual personality. Following on from Hume, he here declares that in his opinion “consciousness” is “the name of a nonentity, and has no right to a place among first principles,” and “those who cling to it are clinging to a mere echo, the faint rumor left behind by the disappearing ‘soul’ upon the air of philosophy.” Thus for James consciousness is, as Richardson puts it, “not a thing or a place, but a process.” There is, James writes,

no aboriginal stuff or quality of being, contrasted with that of which material objects are made, out of which our thoughts of them are made; but there is a function in experience [italics added] which thoughts perform, and for the performance of which this quality of being is invoked. That function is knowing.

At the close of the essay, dealing with the foreseen objection that since we feel consciousness operating within us it must surely exist, he puts forward the wonderful assertion that Kant’s “I think,” which situates objects, should actually be “I breathe”:

Breath, which was ever the original of “spirit,” breath moving outwards, between the glottis and the nostrils, is, I am persuaded, the essence out of which philosophers have constructed the entity known to them as consciousness. That entity is fictitious, while thoughts in the concrete are fully real. But thoughts in the concrete are made of the same stuff as things are.

It would be a mistake to see all this as a negative assault upon our most treasured beliefs about ourselves and our place in the world. One of the most extraordinary things that James ever wrote is the chapter “Concerning Fechner” in what Richardson considers his “boldest book,” A Pluralistic Universe. Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801–1887) was a German pyschologist with, as Richardson remarks, “a playful streak” similar to James’s. The aspect of Fechner’s thinking that James is concerned with is his contention, as James wrote, “that the whole universe in its different spans and wave-lengths, exclusions and envelopments, is everywhere alive and conscious.” This notion of the “alive and conscious” harks back to Plato’s Timaeus in which the world is conceived as a living thing, a kind of divinely fashioned animal; it reflects the pantheism of Spinoza and Wordsworth, and anticipates the Gaia hypothesis of James Lovelock in the 1970s.

The special thought of Fechner’s with which James tells us he is most concerned “is his belief that the more inclusive forms of consciousness are in part constituted by the more limited forms.” “We rise upon the earth,” James beautifully writes, “as wavelets rise upon the ocean,” and Fechner “likens our individual persons on the earth unto so many sense-organs of the earth’s soul…. When one of us dies, it is as if an eye of the world were closed, for all perceptive contributions from that particular quarter cease.” James sets out for us the essence of Fechner’s thought:

We must suppose that my consciousness of myself and yours of yourself, altho in their immediacy they keep separate and know nothing of each other, are yet known and used together in a higher consciousness, that of the human race, say, into which they enter as constituent parts. Similarly, the whole human and animal kingdoms come together as conditions of a consciousness of still wider scope. This combines in the soul of the earth with the consciousness of the vegetable kingdom, which in turn contributes its share of experience to that of the whole solar system; and so on from synthesis to synthesis and from height to height, till an absolutely universal consciousness is reached.

James follows Fechner’s lead in insisting that “there is a continuum of cosmic consciousness, against which our individuality builds but accidental fences, and into which our several minds plunge as into a mother-sea or reservoir.” This may seem woolly-minded to a latter-day, “scientific” taste, and certainly it reveals the Victorian William James at his most feelingly rhapsodic.

Yet James is a philosopher—practical and romantic, down-to-earth and ecstatic, accommodating and specific—whom we need ever more urgently in our own times. In Robert Richardson, whose biography of James is, along with his lives of Thoreau and Emerson, one of the glories of contemporary American literature, the philosopher has found a tireless champion and a perceptive editor. Richardson is that increasingly rare phenomenon among academics, an enthusiast, even a lover, of his subjects. In this book, no less than in the biography, he brings to life this great thinker and rare human being. As he observes of James, with rueful wit, “Even his own children were fond of the man Alfred North Whitehead once called ‘that adorable genius.'”

-

1

Robert Richardson reports how “one evening when the whole family was at work in the living room, each at his or her own studies, William drew a sketch for a frontispiece for his father’s next book. The sketch survives; it shows a man beating a dead horse.” After his father’s death, however, William, in what was probably more an act of filial than of literary enthusiasm, edited and published The Literary Remains of the Late Henry James. ↩

-

2

Minnie was much loved. Besides William James, others who courted her included Oliver Wendell Holmes and the eminent Boston lawyer John Gray; even Henry James Jr., despite his ambivalent sexuality, adored her, and made her the model for his most fascinating and most forceful American heroines, from Daisy Miller through Isabel Archer to Milly Theale, the dying girl in The Wings of the Dove. ↩

-

3

In The Metaphysical Club, Menand quotes Santayana’s “characteristically mordant [and, one might add, opaque] assessment” of James: “He was so extremely natural that there was no knowing what his nature was, or what to expect next; so that one was driven to behave and talk conventionally, as in the most artificial society.” (The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001, p. 77.) ↩

-

4

But as Richardson points out, “James defended ‘incompleteness, “more,” uncertainty, insecurity, possibility, fact, novelty, compromise, remedy and success’ as being authentic realities.” ↩

-

5

Menand does have a point here, as evidenced, for instance, in this passage from James’s Pragmatism:

…As, to papal minds, protestantism has often seemed a mere mess of anarchy and confusion, such, no doubt, will pragmatism often seem to ultra-rationalist minds in philosophy. It will seem so much sheer trash, philosophically. But life wags on, all the same, and compasses its ends, in protestant countries. I venture to think that philosophic protestantism will compass a not dissimilar prosperity.

See William James: Writings, 1902–1910 (Library of America, 1987), p. 540. ↩

-

6

Whom James taught for a time at Harvard. ↩

-

7

In The Gospel of Relaxation, for instance, James writes:

↩I cannot but think that the tennis and tramping and skating habits and the bicycle-craze which are so rapidly extending among our dear sisters and daughters in this country are going also to lead to a sounder and heartier moral tone, which will send its tonic breath through all our American life.

-

8

Although it does make a telling acknowledgment: “Here is the real core of the religious problem: Help! Help!” and for that reason “the coarser religions, revivalistic, orgiastic, with blood and miracles and supernatural operations, may possibly never be displaced.” ↩

-

9

It is still a hefty volume, taking up some 440 pages in the Library of America edition of James’s work. ↩

-

10

“James,” Santayana wrote, “detested any system of the universe that professed to enclose everything: we must never set up boundaries that exclude romantic surprises.” However, the compliment, if such it is, is somewhat blunted on the following page: “But James, though trenchant, was short-winded in argument.” (Santayana, Persons and Places, London: Constable & Co., 1944, pp. 249–250.) ↩

-

11

See for example the passage in “The Will,” from Talks to Teachers and Students, which Richardson includes, in which James discusses how free will operates in us when we face the prospect of getting out of bed on a cold winter’s morning. ↩

-

12

In The Metaphysical Club, Menand tells of Wright sending a thousand-word letter to a lady correspondent explaining why taffy turns white when it is stretched. Here, obviously, was a man who knew the way to a woman’s heart. ↩

-

13

Robert D. Richardson, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), p. 517. ↩

-

14

Wittgenstein revered William James, whose Varieties of Religious Experience was one of the few philosophical works the great Austrian kept on his bookshelf. ↩

-

15

Quoted in Cornel West, The American Evasion of Philosophy (University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), p. 42. ↩