Most people with a special interest in the events of the credit crunch and the Great Recession that followed it have a private benchmark for the excesses that led up to the crash. These benchmarks are a rule of thumb, a rough measure of how far out of control things got; they are phenomena that at the time seemed normal but that in retrospect were a brightly flashing warning light. I came across mine in Iceland, talking to a waitress in a café in the summer of 2009, about eight months after the króna collapsed and the whole country effectively went bankrupt under the debts incurred by its overextended banks. I asked her what had changed about her life since the crash.

“Well,” she said, “if I’m going to spend some time with friends at the weekend we go camping in the countryside.”

“How is that different from what you did before?” I asked.

“We used to take a plane to Milan and go shopping on the via Linate.”

Since that conversation, I’ve privately graded transparently absurd pre-crunch phenomena on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being complete financial prudence, and 10 being a Reykjavik waitress thinking it normal to be able to afford weekend shopping trips to Milan.

Many people all over the world went nuts on cheap credit in the years of the boom—a boom that was in large part built on an unsustainable spike in personal and governmental debt. Michael Lewis has already written a very good book, The Big Short, about the mechanics of the crash, by casting around for people who didn’t just foresee it, but who made huge bets that it would happen, and profited vastly when it did.1

Boomerang is about what he has come to see as the larger phenomenon behind the credit crunch: the increase in total worldwide debt from $84 trillion in 2002 to $195 trillion now. The thesis is that “the subprime mortgage crisis was more symptom than cause. The deeper social and economic problems that gave rise to it remained.” It is these deeper problems that are dominating economic news at the moment, and led to the desperate measures announced at the European summit on October 27 and to the aborted Greek plan to hold a referendum that followed. The G20 Economic Summit of November 3–4 was dominated by discussion of the Eurozone crisis, but ended with no coherent plan in view, and none has emerged since. Boomerang tells the story of how we got here, and in the course of doing so gathers together an extensive arsenal of data at the top end of my 0–10 Reykjavik waitress scale: the fact that Greek railways have €300 million in other costs; the fact that the Californian city of Vallejo spent 80 percent of its budget on the pension and pay of police, firemen, and other “public safety” workers; the fact that between 2003 and 2007, Iceland’s stock market went up ninefold; the fact that in Ireland, a developer paid €412 million in 2006 for a city dump that is now, because of cleanup costs, valued at negative €30 million.

Lewis has noticed something important about these excesses: that the precise details of how people ran amok varied from culture to culture. Cultural and historical faultlines were exposed by the boom, and behavior varied accordingly.

The credit wasn’t just money, it was temptation. It offered entire societies the chance to reveal aspects of their characters they could not normally afford to indulge. Entire countries were told, “The lights are out, you can do whatever you want to do and no one will ever know.” What they wanted to do with money in the dark varied. Americans wanted to own homes far larger than they could afford, and to allow the strong to exploit the weak. Icelanders wanted to stop fishing and become investment bankers, and to allow their alpha males to reveal a theretofore suppressed megalomania. The Germans wanted to be even more German; the Irish wanted to stop being Irish. All these different societies were touched by the same event, but each responded to it in its own peculiar way.

Lewis is an unmatched nonfiction storyteller, and a large part of his talent is the way he attaches his stories to the people who help him tell them. Nonfiction has a payload and a delivery system. In Lewis’s work, the delivery system is usually a man, a forthright contrarian who thinks clearly and talks vividly and whose dissent from the mainstream is not a matter of theory but of practice: Lewis likes people who don’t just speak against the conventional wisdom, but who bet against it, and whose bets come off. His first interlocutor, Kyle Bass, is a classic example. Bass is a fund manager who made a fortune “shorting” toxic mortgage assets, and then became preoccupied by the subject of global debt levels. Bass is, to put it very mildly, a pessimist on the subject of sovereign debt:

Advertisement

Spain and France had accumulated debts of more than ten times their annual revenues. Historically, such levels of government indebtedness had led to government default. “Here’s the only way I think things can work out for these countries,” Bass said. “If they start running real budget surpluses. Yeah, and that will happen right after monkeys fly out of your ass.”

The prognostications that ensue from Bass’s analysis are gloomy, and form the basis of Boomerang’s big-picture overview. “The financial crisis of 2008 was suspended only because investors believed that governments could borrow whatever they needed to rescue their banks. What happened when the governments themselves ceased to be credible?”

Bass thinks that the only reliable investments are guns and gold, and has just bought twenty million nickels, because the metal in a five-cent nickel is worth 6.8 cents, and they are going to be a stable source of value when things go wrong. (If you’re wondering how easy it is to get hold of 20 million nickels, the answer is, not very.) There are many equally vivid pen portraits in Boomerang, usually of forthright contrarians: a super-frank German ex-banker, a doomsaying Irish economist, two Greek tax collectors who hate each other, and the former governor of California.

Schwarzenegger gives an interview while he and Lewis and several advisers go zooming through Los Angeles on their bicycles, part of the governor’s cardio routine:

He wears no bike helmet, runs red lights, and rips past DO NOT ENTER signs without seeming to notice them, and up one-way streets. When he wants to cross three lanes of fast traffic he doesn’t so much as glance over his shoulder but just sticks out his hand and follows suit, assuming that whatever is behind him will stop. His bike has ten speeds but he uses just two: zero, and pedalling as fast as he can….

It isn’t until he is forced to stop at a red light that he makes meaningful contact with the public. A woman pushing a baby stroller and talking on a cell phone crosses the street right in front of him, and does a double take. “Oh…my…God,” she gasps into her phone. “It’s Bill Clinton!” She’s not ten feet away and she keeps talking to the phone, as if the man is unreal. “I’m here with Bill Clinton.”

“It’s one of those guys who has had a sex scandal,” says Arnold, smiling.

Schwarzenegger’s economic adviser gave Lewis some of the facts of the economic scandal:

This year the state will directly spend $32 billion on employee pay and benefits, up 65 percent over the past ten years. Compare that to state spending on higher education [down 5 percent], health and human services [up just 5 percent], and parks and recreation [flat], all crowded out in large part by fast-rising employment costs.

Lewis writes that

the same fiscal year that the state spent $6 billion on prisons, it had invested just $4.7 billion in its higher education…. Everywhere you turned, the long-term future of the state was being sacrificed.

By and large, Lewis’s contrarians tend to be monomaniacs: they are people who have The Answer. It is a feature of the financial world, much remarked by Warren Buffett, that people would rather be wrong in a group than right on their own; the people who insist on being right on their own tend to have the psychological equipment to match. They are hedgehogs rather than foxes, eyes firmly on one big thing. There are times when Lewis himself is a little like that. Boomerang is unlike his previous books, in that it is a series of portraits of whole societies. A writer making society-wide generalizations is picking up a big and very full bag by a single handle; in that position, it’s easy to end up writing about the handle, because it’s the thing on which you have a secure grip.

For the most part, Lewis’s handles are fitted to the heavy lifting he makes them do, with the possible exception of his approach to Germany via the not-at-all unfamiliar idea that the country has a national obsession with excrement. He quotes the American anthropologist Alan Dundes: “Clean exterior–dirty interior, or clean form and dirty content—is very much a part of the German national character.”

That otherwise telling essay is about the state of the euro, a subject of immense importance at the moment for the entire global economy. Since its creation in 1999, the euro has accumulated enormous imbalances between the economies of its member states, with Germany in particular running a big trade surplus and the “peripheral” countries, mainly in Southern Europe, building up an ever bigger mountain of private and individual debt. “There was no credit boom in Germany,” an official told Lewis. “Real estate prices were completely flat. There was no borrowing for consumption. Because this behavior is totally unacceptable in Germany.”

Advertisement

It is, or should be, self-evident that this situation can’t continue forever, but the problem is that the Germans are showing no appetite either for becoming less German—i.e., paying themselves more, consuming more, and importing more—or for open-endedly bailing out the Southern Europeans. “The German people all know at least one fact about the euro: that before they agreed to trade in their deutsche marks their leaders promised them, explicitly, that they would never be required to bail out other countries.” That promise has already been broken, and is set to be broken many times more—though let’s not forget that these “bailouts” are actually loans that in principle must be repaid.

Unfortunately, the bailouts are only the beginning of what is needed to stabilize the euro. The Eurozone summit of October 27 saw the first three steps: a “haircut” imposing losses of 50 percent on creditors who own Greek government debt; a recapitalization of Europe’s banks, to the tune of €106 billion; and an extension of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). Further down the road, some sort of federalization of European debt is surely inevitable. The likely step involves the creation of a eurobond, so that governments can borrow on a continent-wide basis, with continent-wide guarantees of security. Many consequences follow from that, not least, as George Soros has argued in these pages, the need for some sort of Europe-wide treasury to guarantee it.2 That in turn implies the creation of something like a new European ministry of finance, which must surely also have powers of collection and enforcement in relation to taxation.

Say that to Germans, however, and what they hear is that they will be required to pay other countries’ debts—and the painful truth is that yes, they will. The only way of reconciling the economic necessities and political requirements is for Europe to grow closer in its fiscal governance, a process that will involve painful losses of sovereignty and years of difficult adjustment in national habits. The Treaty of Rome, which founded the European Economic Community in 1957, plainly states that its goal was the “ever closer union” of European peoples—but nobody actually believed that would mean anything difficult or costly. That “ever closer union” has now become an economic requirement, one that is likely to bring with it many years of political and fiscal discomfort. In the meantime, “the only economically plausible scenario,” Lewis writes, “is that the Germans, with a bit of help from a rapidly shrinking population of solvent European countries, suck it up, work harder, and pay for everyone else.”

This might sound like a harsh truth, but it’s pretty mild by the standards of Boomerang, because Germany’s economy is in better condition than any other place Lewis visits. It will need to be, because the need for the Germans to pay for the Euro’s failings is only going to grow. The measures announced on October 27 all showed movement in the correct direction, but the sums involved were nowhere near big enough and the mechanism to extend the EFSF looked short on detail. When the steps were announced, attention immediately focused on one number: the price which the Italian government must pay when it borrows money. Italy has to roll over €330 billion of debt next year. The cost of that debt is of huge consequence for the Euro, because if it is too high, Italy won’t be able to pay it back, and if Italy can’t pay it back, then the whole Euro project is in big, potentially terminal trouble.

Unfortunately, the new plan got the thumbs-down: markets nudged the yield on Italian debt dangerously close to 6.5 percent, a number generally regarded as unsustainable. So the October 27 deal, generally seen as an attempt to buy time while more comprehensive plans are made, may not even do that. I don’t think Lewis would be surprised at the way this is playing out, and the fact that the full extent of the debt problems are still not being faced. Some of his targets in Boomerang date from the boom years, but many are firmly located in the present. The angriest of these essays is about Greece, which he sees as a country in the grip of “total moral collapse.”

Corruption and tax evasion are endemic, and successive governments have created a state in which citizens see themselves as deserving beneficiaries of state patronage; they expect to live cushioned from economic realities, and to retire at fifty-five for men and fifty for women if they do something “arduous,” a definition that includes “hairdressers, radio announcers, waiters, musicians, and on and on and on.” Lewis finds Greece seething at the moment, full of outrage at the demands for “austerity” imposed on it from outside: “a nation of people looking for anyone to blame but themselves.”

Even if it is technically possible for these people to repay their debts, live within their means, and return to good standing inside the European Union, do they have the inner resources to do it? Or have they so lost their ability to feel connected to anything outside their small worlds that they would rather just shed their obligations? On the face of it, defaulting on their debts and walking away would seem a mad act: all Greek banks would instantly go bankrupt, the country would have no ability to pay for the many necessities it imports (oil, for instance), and the government would be punished for many years in the form of much higher interest rates, if and when it was allowed to borrow again. But the place does not behave as a collective…. It behaves as a collection of atomized particles, each of which has grown accustomed to pursuing its own interest at the expense of the common good. There’s no question that the government is resolved to at least try to re-create Greek civic life. The only question is: Can such a thing, once lost, ever be re-created?

To Lewis, Greece marks a limit case for just how far a developed society can go off the rails. The other case studies, of Iceland, Ireland, and California, involve a great deal of folly, but those societies don’t refuse to admit the realities quite as absolutely. That’s not to say that Lewis is sparing about the behavior he describes, much of it at the top end of my 0–10 scale. Some of it verges on black comedy, especially in Iceland:

Yet another hedge fund manager explained Icelandic banking to me this way: you have a dog, and I have a cat. We agree that each is worth a billion dollars. You sell me the dog for a billion, and I sell you the cat for a billion. Now we are no longer pet owners but Icelandic banks, with a billion dollars in new assets. “They created fake capital by trading assets amongst themselves at inflated values,” says a London hedge fund manager. “This was how the banks and investment companies grew and grew.”

When the value of those assets collapsed, the banks immediately followed, leaving debts equivalent to $330,000 for every Icelander.

The flavor of the mania in Ireland was different again. There, it was a classic property bubble, one that followed a remarkable period of genuine and sustained economic growth. From the late 1980s, Ireland had a number of good years, during which the economy grew rapidly (hitting an annual high of 11.8 percent), prosperity was widely shared, and the country rocketed up to fifth place in the UN’s Human Development Index. This was succeeded by a crazy excess of speculation in land values, beginning in the early years of the new century and ending with the biggest economic contraction seen in any country since the Great Depression.

The widely shared analysis in Ireland is that the disaster was caused by an unholy trinity of bankers, politicians, and house-builders, and involved a great deal of systematic corruption on the part of all three (especially over issues such as rezoning land). Lewis is gentler on the bankers at the heart of the crash than the Irish themselves are: he thinks that the bubble “wasn’t as cynical” as in other countries. The people indulging in the speculation genuinely believed that they were going to get rich. It was a bubble of greed and stupidity and excess, but not one in which the rich systematically stole from the poor. Perhaps the numbers are so bad that no more grimness needs to be troweled on:

A single bank, Anglo Irish, which, two years before, the Irish government claimed was suffering from a “liquidity problem,” confessed to losses of 34 billion euros. To get a sense of how “34 billion euros” sounds to Irish ears, an American thinking in dollars needs to multiply it by roughly one hundred: $3.4 trillion. And that was for a single bank. As the sum total of loans made by Anglo Irish Bank, most of it to property developers, was only 72 billion euros, the bank had lost nearly half of every dollar it invested.

When the Irish banks collapsed, the state stepped in and guaranteed not just the deposits of their customers, but all the banks’ liabilities. Nobody knows quite why they covered the losses of the bondholders who had lent money to these fundamentally broken companies: but they did, and the promise in turn bankrupted Ireland, leading directly to a European Union and International Monetary Fund bailout. The fallout is going to dominate life in Ireland for years.

It’s a sad story; Boomerang is a sad book, as well as a vivid and funny and enlightening one. Lewis ends it with a tentative glimpse of optimism in the formerly bankrupt Californian town of Vallejo, where a new city manager and a new head of the fire department are finally trying to get the municipality functioning again. In a city of 112,000 people, the fire department was cut from 121 to 67; it handles 13,000 calls a year, most of them pointless. The new fire chief, Lewis writes,

sat down and made a list of ways to improve the department…. He began, in short, to rethink firefighting.

When people pile up debts they will find it difficult and perhaps even impossible to repay, they are saying several things at once. They are obviously saying that they want more than they can immediately afford. They are saying, less obviously, that their present wants are so important that, to satisfy them, it is worth some future difficulty. But in making that bargain they are implying that when the future difficulty arrives, they’ll figure it out. They don’t always do that. But you can never rule out the possibility that they will. As idiotic as optimism can sometimes seem, it has a weird habit of paying off.

Outside the pages of Boomerang, there are glimpses of optimism in both Iceland and Ireland—though the countries have taken interestingly opposite routes to their longed-for recoveries. Iceland defaulted and effectively told financial markets where to stick themselves, administering severe “haircuts” to investors in the process, and let its banks collapse rather than pour government money in to prop them up. (Iceland had no choice: the banks were many times bigger than its entire economy.) The currency crashed, thus boosting exports and cutting imports, and now the economy is growing and unemployment is falling.

Ireland did the opposite: it ruinously stood by its bankrupt banks, stayed inside the euro, and took the medicine of austerity packages; it too is now showing signs of tentative return to growth. Both countries should be able to recover, absent a full European meltdown. A crucial component of both countries’ nascent turnaround has been a willingness to look the severity of their predicament straight in the eye, and tell themselves the truth about it.

That doesn’t mean that Boomerang leaves the reader feeling optimistic; an honest book about the current economic condition of the Western world couldn’t do that. One of the lasting feelings I took away from my own experiences of “financial disaster tourism,” as Lewis calls it, was one of sadness. I went to the same countries and met different people who told very similar stories. It is easy to diagnose a basic failure of responsibility as one of the causes of the debt crisis; and there’s no denying that such failures took place on the widest imaginable scale, from individuals up to governments.

I think, though, that the failure of responsibility was linked to a failure of agency—the individual’s ability to affect the course of events. An enormous number of people today feel as if they have very little economic agency in their own lives: often, they are right to feel that. The decisions that affect their fates are taken far above their heads, and often aren’t conscious decisions at all, so much as they are the operation of large economic forces over which they have no control—impersonal forces whose effects are felt in directly personal ways.

It is difficult to feel responsible when you have no agency. Many of the people who did stupid things—who did things on that 0–10 scale—did so because everyone around them was doing them too, and because loud voices were telling them to carry on. The Icelanders who bought cars with foreign currency loans were sold them by financiers who promised that it was a good idea; the Irish who bought now-unsellable houses on empty estates were told, by builders and bankers and the state, that this was a once-in-a-generation opportunity; the Greeks who are, at the time of writing, furiously rebelling against austerity measures were falsely told that the state could afford to look after them, and arranged their lives accordingly.

The collective momentum of a culture is, for more or less everybody more or less all of the time, overwhelming. This is especially true for anything to do with economics. The evidence is clear: it is easy to mislead people about money, and easy to lead members of the public astray both individually and en masse, because when it comes to money, most of us, most of the time, don’t know what we’re doing. The corollary is also clear: the whole Western world misled itself over debt, and the road back from where we are goes only uphill.

—November 10, 2011

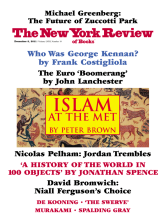

This Issue

December 8, 2011

On the Magic Carpet of the Met

Is This George Kennan?