To the Editors:

More than half a century ago, Czesław Miłosz (who was particularly well placed to comment on such matters) warned us that, contrary to what we tend to assume, our traditions, our social and legal institutions, cannot ensure us any real or permanent protection against gross abuses of state authority:

The man of the East cannot take Americans seriously because they have never undergone the experiences that teach men how relative their judgments and thinking habits are. Their resultant lack of imagination is appalling…. If something exists in one place, it will exist everywhere.

This phrase has a particular resonance for me. For the last five years, I have been engaged in a long, gruesome battle with Belgian officialdom (Belgium—the “Stateless State,” as the regretted Tony Judt aptly called it—is my country of origin). The blunder of a consular official had illegally deprived two Belgian citizens by birth of their sole nationality—reducing them to statelessness. It would have been easy enough to correct the original mistake, but (as Liu Xiaobo remarked in different circumstances; see my essay on pages 53–55 of this issue) the main concern and industry of bureaucrats is not to rectify their mistakes, but to conceal them. The fate of these two young men, suddenly turned stateless by sheer administrative stupidity, is of particular concern to me: they happen to be my twin sons.

A Chinese friend who knows of my predicament remarked that, since over the years I have spent much time denouncing Chinese abuses of power, it would be sensible for me now to look closer to home. He has a point; yet reading Liu Xiaobo has not been a diversion from my duty toward my family: it gave me added awareness that, in the defense of human rights, our fight is universal and indivisible.

One interesting twist in the unfolding of the Belgian government’s denial of my sons’ rights: the diplomat who was the main architect of a cover-up (which still delays the judicial resolution of the affair) recently obtained the posting he long coveted, as a reward for his zeal—he is now ambassador in Peking, where he ought to feel like a fish in the water. Our present Belgian ambassador in Australia, also knowing the truth, came to apologize privately. Unfortunately, he cannot do so publicly; as he said, this would be the end of his career. Why?

Simon Leys

Canberra, Australia

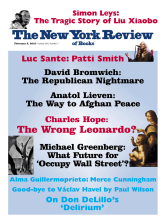

This Issue

February 9, 2012

The Wrong Leonardo?

Václav Havel (1936–2011)

The Republican Nightmare