1.

Created a baronet by William Gladstone, friend of Sarah Bernhardt, and idol of the Symbolists, by the time of his death in 1898 Sir Edward Burne-Jones was the most celebrated English artist in the world. To his admirers, his art represented the culmination of a literary tradition in painting that stretched back to the Renaissance. But to be a literary painter at the end of the nineteenth century was to be on the wrong side of history. Soon enough his reputation would begin its long descent into twentieth-century oblivion.

He sensed this, and was defiant. When a studio assistant told him that French Impressionism was not “based on literature,” he snapped, “What do they mean by that? Landscape and whores? That’s what they want—nothing but landscape or if any figure pictures more or less languid whores.” His own paintings, he added, were “so different to landscape paintings. I don’t want to copy objects; I want to tell people something.”

The exhibition staged by the Tate Gallery in June 1933 to mark the centenary of his birth was therefore something of a bittersweet occasion. Among those present at the private viewing was the artist’s old friend the collector and aesthete W. Graham Robertson, who looked around at his fellow guests and saw “a little crowd of forlorn old survivals paying their last homage to the beauty and poetry now utterly scorned and rejected.”1

From this nadir, things could only improve. Writing in Horizon in 1940, the neo-Romantic critic Robin Ironside defended Burne-Jones’s Romantic Symbolism against Clive Bell’s idea of “significant form” by arguing that a picture’s poetic content was every bit as important as its formal properties. Scorning fashion, Ironside drew parallels between Burne-Jones, the British Visionary, and the French Symbolist Gustave Moreau.2 In the 1960s art dealers, collectors, and writers began to take an interest in his work, but not until 1975 with the opening of John Christian’s pioneering retrospective at the Hayward Gallery and the publication of Penelope Fitzgerald’s delightful biography did a full-scale revival get underway. Today his is once again a household name—and yet as an artistic personality he remains curiously elusive. There is something about Burne-Jones’s work that still needs to be explained, something that has not yet been said.

In The Last Pre-Raphaelite, Fiona MacCarthy identifies that something as the sublimation of desire into art. Aimed at the general reader, her thoroughly researched biography changes our perception of the man and his art by exploring in depth aspects of his life that an art historian might only consider in passing. In recognizing the undertow of melancholy and sexual frustration embedded in work of hypnotic visual power, she articulates what the illustrator George du Maurier called the “Burne-Jonesiness of Burne-Jones.”

By contrast, in his superb study of painting in England during the 1860s, Allen Staley sees Burne-Jones as one of a generation of artists who took British painting from the tight Pre-Raphaelite style that prevailed in the 1850s to the beginning of the Aesthetic Movement. By using formal analysis to delve deeply into Burne-Jones’s artistic training, working method, and absorption of a broad range of artistic influences, he helps us to understand how he came to be the artist he was. No artist works in isolation. During the single decade 1860–1870 Burne-Jones developed and changed in relation to the art of contemporaries like G.F. Watts, Simeon Solomon, James McNeill Whistler, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Giving a chapter to each artist, Staley considers their personal background, private life, and personality—but only insofar as it helps to elucidate, picture by picture, the complex creative process whereby stylistic change takes place. It is a tour de force.

2.

Born four years before Queen Victoria came to the throne, Edward or Ned Jones (the “Burne,” the hyphen, and the “Sir” all came later) had a childhood that sounds more dingy than grim. When his mother died giving birth to him, his inconsolable father employed a loving nurse to raise the child in rooms above his carving, gilding, and frame-making shop in Birmingham, the smoke-blackened lung of the industrial Midlands. Academic success as a day boy at King Edward VI’s School and his decision to read for the priesthood led to a place at Exeter College Oxford. There, in 1853, he met the eldest son of a wealthy London stockbroker who changed his life. Medievalist and bibliophile, William Morris fired Ned Jones with his precocious love of Gothic cathedrals, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts.

Inspired by the idealism of John Henry Newman and steeped in the chivalric romances of Malory, Scott, and Tennyson, the two young men inhaled the incense of Anglican High Church ritual and together made plans to establish a lay brotherhood in the slums of London. On a walking tour of northern France in 1855, Morris showed his friend the great Gothic cathedrals at Amiens, Rouen, Beauvais, and Chartres. In Paris he took him to the Louvre where he led him straight to Fra Angelico’s Coronation of the Virgin.

Advertisement

The journey transformed everything. The following year the pair left Oxford without taking their degrees and moved to London—Morris to train as an architect, Jones to become a painter. Both married—Morris to the strikingly beautiful daughter of an Oxford groom, Jane Burden, and Jones to one of the five remarkable daughters of a Methodist minister, Georgiana Macdonald.3 Though they abandoned plans for a monastic brotherhood, their dream of living in communal fellowship remained very much alive when, together with the painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown and the architect Philip Webb, Morris came to furnish and decorate Red House, the country retreat Webb designed for him near Bexley Heath in Kent.

Out of their designs for hand-painted tiles, embroideries, wall paintings, and painted furniture would emerge the firm in which Ned was a founding partner, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (later Morris & Co.). For the next two decades the pitifully small amounts Morris paid him for his stained-glass designs became a steady source of income to supplement the early patronage of collectors like William Graham and Frederick Leyland. As both Staley and MacCarthy emphasize, his work in the decorative arts is as significant as his painting.

Largely self-taught, Burne-Jones learned to draw and paint through imitation. Soon after his arrival in London in 1856 he found his first mentor in the Pre-Raphaelite poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Five years older than Ned, Rossetti recognized the expressive urgency and innocence of the earliest drawings, overlooking the hesitant draftsmanship and imperfect technique. Vehemently anti-academic, he opposed any attempt by his protégé to improve his draftsmanship by the traditional means of drawing from the antique, because “such study came too early in a man’s life and was apt to crush out his individuality.”

In an early pen-and-ink drawing, Going to the Battle (1858), the vaguely Arthurian subject, the flattening of two-dimensional space, and the use of delicate overall hatching are inspired by Rossetti, but the fairy-tale landscape in the distance could only have come from the illuminated manuscripts he studied with Morris at the Bodleian Library. What is specifically Burne-Jones’s in the drawing is surprisingly hard to put your finger on, though the delight in decorative patterning and inclusion of frivolous details like a pet parrot on its perch in the foreground would be characteristic of his later work.

In 1860 Burne-Jones taught himself to paint in watercolor, or rather an opaque mixture of gum, water, and body color that was easier to handle than transparent color. Gaining mere competence in the new medium took time, but four years later he had attained proficiency enough to be elected an associate member of the Old Water-Colour Society (later renamed the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours). In a touchingly naive early example, The Madness of Sir Tristram, you sense the young artist straining to transcend his own technical limitations—and in doing so capturing feelings he knew well from personal experience, the inarticulate yearnings of adolescence.

Two tours of Italy in 1859 and 1862 introduced him to Venetian and High Renaissance painting.4 Staley shows, picture by picture, how Burne-Jones joined the vanguard of a generation of young British painters who in the 1860s turned away from Pre-Raphaelite medievalism and toward classical breadth and volume. Stimulated by the recent rearrangement of the Parthenon marbles in the British Museum, he now drew obsessively from the antique. This is how Burne-Jones transformed himself into a virtuoso draftsman with an instinctive feel for the cadences of complex figure compositions. One of the earliest pictures in which you can see this happening shows a female figure in classical dress playing a lyre for another woman, who is bent over in grief. In The Lament (1865–1866) Burne-Jones’s concern is not to tell a story but to manipulate the viewer’s emotions. As in the work of James McNeill Whistler and Albert Moore at this date, delicately restrained colors and exquisite compositional balance are used to create the slow dream-like atmosphere.

With his newly acquired skill as a draftsman came the ability to draw the nude—until now conspicuously absent from his work. The subject of one of the first important pictures in which nude figures appear is taken from Ovid’s strange tale of the wood nymph Phyllis’s love for the mortal youth Demophoön. In Burne-Jones’s alarming conception of the myth, a distinctly modern-looking woman with a mass of streaming hair emerges from a tree to lock her arms around the torso of a naked young man who flees her embrace in terror. What gives the scene its neurotic edge is the way the man recoils from what is clearly depicted as female lust. But what offended the artist’s contemporaries was not this—it was the absence of drapery or a fig leaf covering the man’s genitals. When Burne-Jones submitted the picture to the 1870 exhibition at the Old Water-Colour Society he must have known it would cause a certain frisson among some of the more conservative members. It did; the picture was removed; he resigned; and he did not exhibit in public again until 1877.

Advertisement

There wasn’t much the Victorian public objected to in art as long as the artist was a family man and/or behaved with a modicum of discretion. Public scandal, though, was a serious business. It might have been possible for Burne-Jones to exhibit a full-frontal male nude at the Old Water-Colour Society in 1870—had the nymph in hot pursuit of him not been instantly recognizable as a portrait of the woman with whom he had been involved in a sexual scandal only a year earlier.

Maria Zambaco was the exotic Greek artist who had earlier left her husband in Paris and with whom Burne-Jones had begun an affair in 1866. During its most intense phase their tumultuous relationship lasted about three years. Erotically obsessed with her as he was, Ned would not abandon his wife and children to live with her in Greece. Maria refused to accept his decision to end the affair. In Rossetti’s telling, matters came to a head in January 1869 when Maria “provided herself with laudanum for two at least” and on a night of thick fog walked with Ned through gas-lit streets the considerable distance from Holland Park to the area north of Paddington known as Little Venice. When the lovers reached a bridge over the Regent’s Canal, the distraught Maria attempted to fling herself into the water. Then the police arrived. Rossetti was amused to recount how the “bobbies [collared] Ned who was rolling with her on the stones to prevent [her suicide].”

Shattered, Ned tried to leave the country, but he became so ill that he was forced to return home to be nursed back to health by his wife. The arid marriage between Georgie and Ned survived, but years later he wrote to Frances Horner (daughter of his patron William Graham) of “how often I tried, with all the strength I could, years ago to be free—knowing there was nothing for me but pain, on that road—and I never never could.”

But Maria’s sexual allure had a galvanizing effect on Ned’s work, for she appears in some of his most inspired pictures—as the sorceress in the Wine of Circe, the witch in The Beguiling of Merlin, and the demonic sprite in Phyllis and Demophoön. During the “seven blissfullest years” after his resignation from the Old Water-Colour Society, what he had been through with her enabled him to infuse the academic neoclassicalism of the 1860s with a deeper level of emotional truth, self-revelation, and psychological complexity. Now working in oil paint on a much larger scale, he also returned to a degree to the medievalish settings, costumes, and props of the earlier works.

In one of the most memorable pictures of the 1870s, Laus Veneris, the goddess of love and her four attendant female musicians fill the shallow foreground space, awaiting the return of the wandering knight Tannhäuser and his men, who are glimpsed in the distance through a window in the background. What is new is a mood of languorous eroticism. Sensuous textures and deep, saturated colors are used to create a sultry atmosphere of stifled desire. Burne-Jones learned a lesson from his run-in with the Old Water-Colour Society: everyone in the picture is fully clothed and yet the effect is of a hothouse simmering with sexual tension.

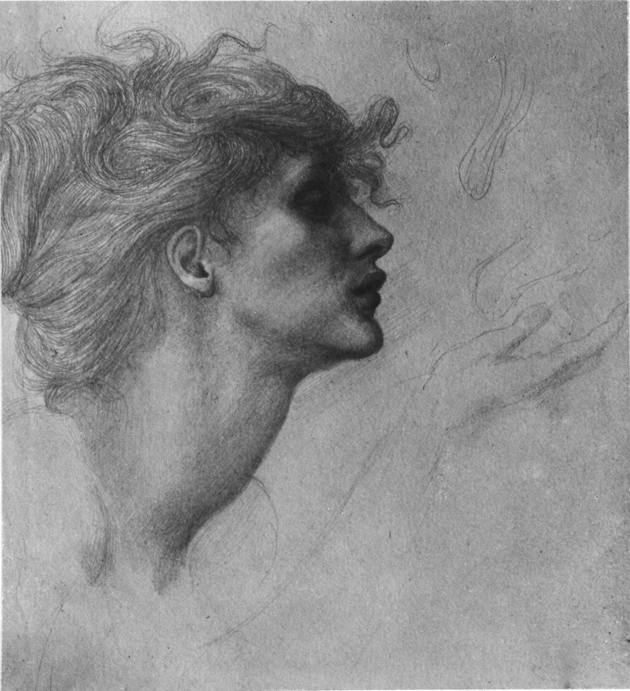

That is because Maria is present, although indirectly. A highly finished pencil study of Maria in profile entitled Desiderium from the same year as he began Laus Veneris makes explicit what is only implied in the painting.5 Even in its present form the erotic charge in Desiderium is startling. With her disheveled hair, flushed face, half-closed eyes, and parted lips Maria is in an unmistakable state of sexual arousal. And that state of excitement is being caused by something she appears to be looking at but that is no longer there. At some point before 1910 when Burne-Jones’s son Philip presented the drawing to the Tate Gallery, the sheet was cut down just to the right of the woman’s face.

The excised area showed Maria fondling the testicles of an erect penis. This can be seen in a photographic reproduction (platinotype; see illustration on page 16) of the original drawing made by Burne-Jones’s friend and neighbor, the Victorian photographer Frederick Hollyer. Though the sexual organs are delineated in graphic detail, it can take a minute or two to make them out because Ned applied less pressure on his pencil to draw them. His intention was to create a vaporous effect, as though the genitals were a miasma Maria had conjured up as she fantasizes about having sex with her lover.6

3.

To the public Burne-Jones was famed for his paintings of angels and virginal young women. But in private, his closest friends and associates were notorious for flaunting Victorian codes of sexual morality. Rossetti lived openly in an adulterous relationship with Jane Morris. Algernon Swinburne’s obsession with flagellation was public knowledge.7 In 1873 Simeon Solomon was jailed for a fortnight for the crime of attempted sodomy in a public lavatory. About all this Ned was clearly broad-minded. Scalded by scandal himself, he understood that in art what is hidden or implied can be more telling than what is made explicit. It is the hints of perversity and cruelty in an atmosphere of trance-like longing in late pictures like The Depths of the Sea (1887) and The Car of Love (1891–1898) that make him so much more interesting an artist than, say, John William Waterhouse. To paint such images, Burne-Jones turned his back on nature, as though he pulled down the blinds of his studio, the better to cultivate his beautiful—and often violent and erotic—fantasies.

But it wasn’t all heavy breathing. He also had great fun exchanging obscene and blasphemous letters and drawings with his friends. Thanking Swinburne for a filthy and obviously very funny letter he had just received, he writes that he had read it aloud to Solomon:

And our enjoyment was that we spent a whole morning in making pictures for you, such as Tiberias would have [given] provinces for. But sending them might be dangerous, and might be inopportune, so we burnt them. One I shall repeat to you. It was my own poor idea, not altogether valueless I trust. A clergyman of the established church is seen lying in an ecstatic dream [i.e., tumescent] in the foreground. Above him a lady is seen plunging from a trap door in the ceiling, about to impale herself upon him.

My only slight criticism of Edward Burne-Jones: The Hidden Humorist, John Christian’s delightful selection of Burne-Jones’s caricatures and cartoons in the collection of the British Museum, is that it doesn’t include any showing the pint-sized Swinburne and Adah Menken—the strapping American equestrienne, circus performer, and dominatrix with whom he was infatuated. The selection Christian does publish suggests that such drawings were likely to have been mildly risqué rather than actually obscene. None of the ones in the British Museum showing naked fat ladies and sumo wrestlers would stimulate fantasy, although it is easy to imagine how one in which he depicts the rotund architect William Burges in bed could be altered to illustrate the clergyman’s “ecstatic dream.”

4.

When Burne-Jones did start to exhibit again in public it was at the opening exhibition in 1877 of the Grosvenor Gallery—the gathering place of artists and writers, royalty and society that instantly became synonymous with the Aesthetic Movement. During the next two decades English painting and sculpture went through an unusually fecund period as successive waves of Aestheticism, Symbolism, and Decadence were grafted onto ingrained traditions of Romantic and Visionary art.

No pictures by Burne-Jones epitomized these tendencies more perfectly than the four canvases that make up the Briar Rose series. When first shown at the art dealer William Agnew’s in 1890, the line to see them snaked all the way down Bond Street and carriage traffic in Piccadilly ground to a halt. As installed today at the National Trust property Buscot Park in Oxfordshire, the four scenes hang in elaborate frames high on the walls and at some distance from each other. But as originally conceived the series formed a single unified composition divided into four parts, with Prince Charming opening the story at the left, and ending with the sleeping figure of Princess Aurora at the right. In between we move from the enchanted wood littered with the entwined bodies of sleeping knights, through the Council Chamber where wise men slumber, and past handmaidens dreaming by the courtyard fountain until we reach the sleeping princess on her embroidered palanquin.

In this slow-motion world, time stands still. The action has either taken place in the past or will take place in the future. For the present, nobody moves. The prince appears to have neither the will nor the desire to bestow the kiss that will wake the princess. He is frozen with indecision as though asking himself whether a state of eternal dreaming is not preferable to the reality of waking to life. The picture epitomizes the decadent tendency in British art not because of the subject or painting technique, but because of its undertow of fin-de-siècle melancholy, a turning away from reality, a fear of life itself.

For those outside the rarefied artistic and intellectual circles in which Burne-Jones moved, this was only part of what was suspect about Aestheticism, an imperfectly understood movement that carried with it a worrying whiff of forbidden and perhaps slightly rotten fruit. If artists and writers went on and on about beauty without saying a word about God or Nature, where would it all end? The answer, it turned out, would be Reading Gaol.

George Du Maurier’s cartoons lampooning the Aesthetes in Punch between the years 1873 and 1881 would help make Burne-Jones famous, but also caused a temporary estrangement between the two old friends. I think what Burne-Jones minded was not being mocked in the cartoon character of the pretentious painter Maudle surrounded by a bevy of “intense” aesthetic maidens. He was annoyed at the way Du Maurier came close to the knuckle in his caricatures of the effeminate, sexually ambivalent poet Jellaby Postlethwaite, the alter ego of Oscar Wilde. Ned knew from personal experience that innuendo could be dangerous—not only for Wilde but for any artist the public associated with Aestheticism.

Wilde is the malign spirit presiding over the second half of “The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement in Britain, 1860–1900,” the groundbreaking exhibition about Aestheticism in all its forms that opens at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco this month, after having already been seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Musée d’Orsay. Ned and Georgie became friendly with the self-appointed leader of the Aesthetes soon after the Grosvenor Gallery opened. If only because he had been so close to Solomon, Ned may well have had some sense of Wilde’s sexual proclivities. But whereas he tried to help Solomon in his trouble with the law, when Wilde was tried for indecency in 1895 Ned angrily disowned him as “that horrible creature who has brought mockery on every thing I love to think of, at the bar of justice to-day.”

In his eyes Wilde’s crime was not the one for which he was convicted, but that by his reckless behavior he had brought Aestheticism itself into disrepute. He saw with horror that Wilde’s conviction would have catastrophic consequences for art in England—and it did.

In some quarters art was already synonymous with moral depravity and therefore a threat to the very fabric of society. Referring to Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for the first number of The Yellow Book (April 1894), a reviewer called for “an Act of Parliament to make this kind of thing illegal.” Those sound like strong words to use about mere drawings until you understand that “this kind of thing” could easily be construed to refer to the crime for which Wilde was sent to prison. After his trial artists associated with Aestheticism, whether gay or straight, were made to feel uncomfortable at home. In the climate of intolerance that prevailed in England in the second half of the 1890s and beyond, James McNeill Whistler, Walter Sickert, Beardsley, and Alfred Gilbert all for different reasons left England to spend time abroad—in Paris, Dieppe, Mentone, and Bruges. With the deaths of Beardsley and Burne-Jones in 1898 the splendid late flowering of British Romantic Symbolism came to an end.

This Issue

February 23, 2012

Can We Have a Democratic Election?

The Super Power of Franz Liszt

-

1

Between 1928 and 1956 the National Art Collections Fund, a private charity that acquires art for the nation, purchased only a single picture by Burne-Jones, and when Christie’s held a sale of Pre-Raphaelite pictures from the Lady Lever Art Gallery at Port Sunlight near Liverpool, his large study in colored chalks Love and the Pilgrim sold for 45 guineas. See Richard Dorment, “Realists and Romantics,” introduction to the exhibition catalog Pre-Raphaelite and Other Masters: The Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection (Royal Academy of Arts, 2003), p. 11. ↩

-

2

Robin Ironside, “Gustave Moreau and Burne-Jones,” Horizon, June 1940. ↩

-

3

Through Georgina’s sisters, Burne-Jones became uncle to Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin, and the brother-in-law of the eminent Victorian painter Sir Edward Poynter. ↩

-

4

A third and last visit took place in 1871. ↩

-

5

Desiderium seems to confirm gossip that although Maria moved to Paris and in time remarried, the affair continued for several more years, though discreetly. ↩

-

6

MacCarthy says the presence of pornographic details in the Hollyer photograph is only a “tempting thesis,” but in fact several prints of the photo are known, and the explicit details I have described are perfectly clear. I am grateful to Rupert Maas for sharing his thoughts on Hollyer’s facsimile with me and for allowing me to reproduce it here. He points out that the initials, date, and inscription we see on the drawing today are absent in the Hollyer facsimile. They must therefore have been added after the work was photographed and cut down, probably by Philip Burne-Jones, who was also an artist. “It was one of the first things the Tate acquired by this important artist,” Maas writes, “and so Philip would have been fully aware of the need for it to be (a) a very good one and (b) properly signed, etc., and, I argue (c) sanitised for posterity.” ↩

-

7

As was Swinburne’s dedication to Ned in 1866 of that hymnal of the Decadent movement, the Poems and Ballads. ↩