During the past century, how many Republican challengers have unseated Democratic presidents? Hint: there have been eight such bids. Answer: only one, when Ronald Reagan turned out Jimmy Carter in 1980.1

This year, the GOP will be trying again. To do so, it will have to muster a majority for Romney and Ryan; in the electoral college, of course, but also among the voters, if it wants a victory viewed as legitimate. This can’t be taken for granted, even with high unemployment and torrents of money on its side. In embarking on this review, I looked for post–World War II books examining the party’s prospects. After Dwight Eisenhower’s sweep in 1952, Louis Harris asked, Is There a Republican Majority? His answer then was “not yet,” hinging on whether the party could cement its toehold in the burgeoning suburbs. Following Richard Nixon’s win in 1968, Kevin Phillips felt he could speak of The Emerging Republican Majority, based on luring Southern Democrats and George Wallace’s adherents in the North. While those gains have been made, a hard fact is that there’s been no rise in the number of voters ready to say the GOP is their party. Nor could I find any books, even by the faithful, forecasting a grand Republican future.

1.

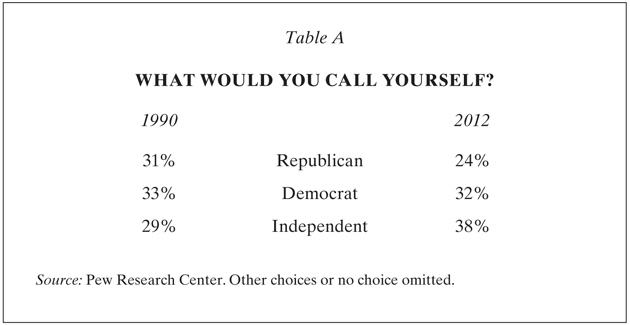

Much-needed background for November’s races is in a recent report by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press titled Trends in American Values: 1987–2012, based on some 450,000 interviews over the quarter-century it covers. A useful supplement is The Oxford Handbook of American Elections and Political Behavior, with articles by sixty-five political scientists showing what their discipline can tell us. (The Pew Center, a widely respected polling organization, is no longer controlled by the Pew family, which once financed varied conservative causes, much like today’s Koch brothers.) The figures in Table A, printed here from the Pew report, had better be posted in every Romney office. Most striking, of course, is the plunge in the percentage of voters willing to call themselves Republicans. This decline has been long building, and not wholly due to George W. Bush’s record. Down to not quite a quarter of the voters, the GOP will need a surge of outside recruits if it hopes to win this year. That Democrats have held steady suggests a continuing loyalty to Obama, despite some dissent in the party’s liberal wing. (Eight years of Bill Clinton taught stalwarts they can’t expect to get all they want.) Indeed, Pew interviews found half again as many Democrats as Republicans praising their party for “standing up for its traditional positions.” Lower GOP enthusiasm probably stems from the post-primary pique of supporters of Rick Santorum, Michele Bachmann, and especially Ron Paul, who still aren’t sure whether Mitt Romney believes in anything.

Romney’s choosing Paul Ryan as his running mate is, by any reading, a desperate decision. Despite his primary victory, which was not overwhelming, it was becoming clear that Romney was not securing a personal following. Had his party’s right wing opted to sit out this election—as many did with McCain—there would be no way he could win. Of course, Ryan is known for his abhorrence of “entitlements,” which he argues will turn America into a Greece.2 The GOP is now gambling that an electoral majority can be brought to this view. What Democratic candidates will need to stress is that the current programs benefit all classes. Not just Social Security and Medicare, but assisted living for the elderly, aid for children with disabilities, as well as support for college loans, along with, for example, a reliable postal service and some funding for the arts. Until recently, Ryan’s status as the GOP’s economics guru meant little notice was accorded to his views on “values.” In fact, he is ultramontane about abortion, even opposing contraceptives that might displace a fertilized egg. While Romney is slightly less extreme—allowing for abortion in cases of incest or rape—the formal party platform permits no exceptions at all. The Pew survey found that 83 percent of adults it interviewed refused to go this far.

But I part company with the Pew authors on their subtitle. Partisan Polarization implies that both parties have abandoned the center. This suggestion of a preexisting “balance” has become all too familiar; and here it simply isn’t true. Indeed, Pew’s own findings over time show no Democratic parallel to GOP shifts to the right. In 1987, fully 62 percent of Republicans favored some kind of social safety net and 58 percent saw some good in unions, signs of a then moderate majority. Today, only 40 percent and 43 percent hold those views. As recently as 1992, a hearty 86 percent were saying they favored environmental regulation of some sort. Today, with a purer party, it’s down to 47 percent.

Advertisement

Given the seven-point drop in regular Republicans and the nine-point increase in independents, it has to be that most of the latter have defected from the GOP. Can they be won back, at least for 2012? On a central issue, a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study may have a few answers.3 Much of the Republican campaign hinges on outright repeal of the Affordable Care Act, always called Obamacare, to give it an alien tinge. The party’s premise is that most middle-class citizens can be convinced they stand to lose if it is put in place.

But the Kaiser study uncovered some unsettling facts. It found that over half of insured adults were delaying or skipping some health care because of high out-of-pocket costs. Almost 40 percent of those earning over $90,000 are cutting back on needed medical attention, as are 60 percent of those aged fifty to sixty-four. It’s not likely that many will figure to do better with a GOP plan that promises to increase choice. If Medicare is now a middle-class staple, Democrats need to convey that the ACA should also be seen as essentially continuing it, which it does, and is not just a program for the poor.

Since the close of Reconstruction, the GOP has been seen as the party of the top bosses—there’s really no other way to put it. Theirs is a long lineage of the one percent. So its candidates try to amass majorities by diversions ranging from race and firearms, to abortion and immigration. The party also makes a place for persons below the median in income who seek to enhance their status by allying with the well-to-do. This is no small pool, as can be seen from the following of Rush Limbaugh listeners on his six hundred stations.

Thus far, Romney’s campaign has chosen to make the economy his principal plank, claiming that he brings talents for creating jobs. Americans understand that it is bosses who decide when they’re ready to add workers. But even people with jobs are seeing that employers are paying as little as possible to get the hands and minds they need. And of such jobs as they’ve been creating, even before the recession, fewer than ever carry what were once standard benefits.

Paul Ryan’s selection as a running mate has brought to the fore his plan to replace Medicare with vouchers, at a time when this program is becoming a central campaign issue. To divert attention, Republicans have begun arguing that their repeal of the Affordable Care Act will actually preserve Medicare funding. Here the issue is less alleged amounts—$700 billion has been cited—but whether voters will believe the GOP is committed to this admittedly expensive entitlement.

On each issue, the Pew study lists the responses of Republicans, independents, and Democrats. What stands out is that in almost all cases, independents are much closer to Democrats, often by substantial margins. This is most apparent in how they regard Wall Street and concentrated wealth, the use of military power, and blame for mortgage defaults. If most of these independents were once Republicans, they’ve put some distance between themselves and the party. A margin of GOP primary voters gave Romney the edge, feeling that an ideologically purer nominee would scare away the middle. Even so he will be identified with the generic GOP label, with the obduracy of John Boehner’s House of Representatives, and especially with Paul Ryan’s budget plan, which will be the de facto party platform. All this is not a sure bet for enlisting independent enthusiasm.

Most voters support straight party tickets most of the time. Even so, nowadays not many openly proclaim, “I am a Democrat” or “I am a Republican.” To do so sounds like allowing you are in a party’s pocket—the party can count on you. In fact, at one time or another, almost everyone has chosen candidates from the other side. Still, as the Pew study has made clear, more people are now choosing to identify as independents. Since most national elections aren’t landslides, it’s tempting to conclude that nonpartisans determine the winner. Thus they’re tagged as “undecideds,” “uncommitteds,” or simply “up for grabs.” In this vein, the Romney campaign must be inquiring into such loose categories as soccer moms and tailgate dads, as well as looking to revive Reagan Democrats. The premise is that it’s the swing voters who swing elections. But do they?

William Jacoby at Michigan State University, an Oxford Handbook contributor, prefers to call such people “hidden partisans.” When prodded, he points out, they “admit that they lean toward either the Democratic or Republican parties.” The real test comes further down on the ballot, when they face largely unknown names. In fact, once in the booth, most people vote all the way down. Some follow the party of the first person they supported, the storied “coattails” effect. But most see it as a time to come to the aid of “their” party, and that’s what they do.

Advertisement

This has been cast as a defensive year for Democrats at all levels. The GOP is still riding on its 2010 sweep of the House, along with eleven governorships. This confidence may be misplaced, as I’ve pointed out in these pages.4 Republican candidates in these House races attracted a total of fewer than 45 million votes, well below the some 67 million they will need this year for a presidential majority. Midterm turnouts are always smaller, largely because the candidates aren’t as well known. The 2010 electorate was also older, conspicuously white, and invigorated by its Tea Party allies. Indeed, over the past two years, the Tea Party has been exerting itself within the GOP, rallying its cadres to unseat moderates like Senator Richard Lugar in Indiana and to install the conservative Ted Cruz as a senator from Texas. But 2012 will bring a much larger and more varied number of voters to the polls. And insofar as the Pew Center’s analysis of independents is accurate, it’s unlikely that many of them will look to the Tea Party for guidance.

2.

Polling seems an obvious corollary to democracy. While everyone has opinions, most are voiced to family and friends, if they are voiced at all. Hence the emergence of an industry devoted to approaching people and asking their views, with the results duly recorded. For the 2012 part of the Pew report, a sample of just over three thousand adults were asked eighty-five or so questions, mainly on political issues. But some plumb deeper, providing telling glimpses into Americans’ lives. Thus we learn that 76 percent say prayer figures strongly in their lives. Or that while 62 percent of women feel that single parents can do as good a job as a couple, only 39 percent of the men who were questioned do.

So it’s appropriate to ask how reliable the figures are. But before addressing that issue, it would be well to note another use of polls: predicting how elections will turn out. Here the concern is less specifically with what’s on people’s minds than about a particular act they will perform. If predictive polls are used internally to direct campaigns, others parse the percentages, if only to see how their favorite is faring. A third type of question seeks to elicit information, like how many sex partners we’ve had, or whether we can name our congressional representative.

All polls face similar challenges, like how items are worded or how many options are provided. But two challenges are paramount. The first is to secure a cross-section sample, whether of the whole population or only likely voters. The other is whether those chosen will be telling the truth. Generally, a national sample of three thousand is viewed as credible, whether for all 235 million adults or an election that may attract 130 million voters. While it may seem counter to common sense, a sample’s numerical size has been found by the polling organizations to be all that matters, not its fraction of the total. That said, polling can be frustrating work. Pew says it can’t reach 38 percent of the people it wants to interview, because they’re seldom in or no longer have land telephones. And even when contact is made, only 14 percent agree to answer questions. Other organizations admit to similar difficulties.5

As matters now stand, polls try to winnow a reliable sample from those who do respond. At this point, I’m prepared to credit, with caution, most of their results. After all, the 2008 presidential polls in Table B came within three points of predicting that year’s actual results, as did most others, which is what’s expected with the samples they used. (A finer edge would need a sample several times larger, well above polling budgets.) No one criticized NBC or ABC or other organizations for being a few points off. Luckily for them, 2008 had a fair-sized spread between losers and winners. In the last week of 2000, all the polls found Bush and Gore so close that they said it wasn’t possible for them to call a winner. They knew better than to make a stab and get it wrong.

But in another 2008 vote, a careful sample wasn’t enough. In California, a proposition that only heterosexuals might marry was also on the ballot. As can be seen in Table B, two reputable polls badly miscalled the result. It’s not that people made up or changed their minds in the final days. The truth was that some proposition supporters weren’t speaking frankly about their intentions. Perhaps they didn’t want to appear bigoted, even if those hearing them were interviewers they didn’t know and would never encounter again. Such trimming also occurs in contests where one candidate is black, and may explain why McCain’s poll percentages were below his actual showing. Respondents may well have been reluctant to say that they’d rather not vote for a black man. This will be something to watch out for in 2012.

Since most predictive polls do their job within stated margins, this suggests to me that opinion surveys with similar samplings are valid enough to trust. So I felt sufficiently confident about Pew’s findings to rely on them for this review. Still, I have some caveats. For instance, there are what I would call “induced” opinions. Here I mean views that people don’t have until an interviewer poses a question. It’s a bit like trees falling in a lonely forest. So when Pew asked if “we should get even with any country that tries to take advantage of the United States,” fully 92 percent were willing to be recorded as agreeing or disagreeing. Yet in matters as unsettling and vague as this, most of us have a mélange of reflections and reactions, and aren’t ready to say anything conclusive. The Chinese may take advantage of a low US tariff that is a benefit to American consumers and a heavy burden on Chinese workers. Polls can be useful if they elicit what people have on their minds. But it’s something else for polls to act as agents provocateurs, prompting positions that hadn’t hitherto been held.

In fact, most Americans don’t keep abreast of what’s behind the headlines. So it remains to ask how the views they do have get formed. In my view, the best explanation was provided a half-century ago, by a pair of sociologists named Elihu Katz and Paul Lazarsfeld.6 They descended on Decatur, in downstate Illinois, to find how people informed themselves. “Do you know anyone around here who keeps up with the news,” they asked, “whom you can trust to let you know what is really going on?” Almost everyone did, mentioning someone in their circle who could explain, say, who will benefit from a proposed change in tax rates. Today, there might be a daughter-in-law who keeps tuned to National Public Radio or subscribes to The Economist. Katz and Lazarsfeld called these individuals “influentials,” not because they were prominent, but because friends and fellow workers listened to them.

My sister in upstate New York is such a go-to person. She’s among the first to meet potential political candidates in living rooms, and she passes on her impressions. So we shouldn’t expect voters to be fully informed. Rather, there is what Katz and Lazarsfeld called a “two-step flow,” whereby citizens basically choose their own experts to help them make sense of the political swirl. Whether the people they listen to—and of course they may listen to more than a few—are actually well informed or just articulate presents a large question for American democracy. Of course, what’s different today is that personal circles are wider and more ethereal, especially as more people rely on like-minded blogs and commentators to interpret the political swirl.

3.

If the Fifteenth Amendment made voting a right conferred with citizenship, Michael McDonald at George Mason University sees one of our major parties as never fully committed to that right. “Republicans speak of voting as a privilege,” he writes in the Oxford Handbook, “that should be granted to people capable of meeting minimal standards imposed to safeguard the electoral process.” In the past, such standards included owning property, passing a literacy test, or remitting an annual tax. As is now well known, Republican legislatures in every region, emboldened by their 2010 sweep, are requiring would-be voters to produce a state or federal document containing their photograph.

A passport will do; but half of adult Americans haven’t one. Some states allow hunting licenses and gun permits; but the most widely held is of course a driver’s license. Widely held, true, but far from universal. Republicans know that city dwellers, more a Democratic constituency, are less likely to own or rely on cars. Counter to popular images, many teenagers never get behind a wheel. According to the Federal Highway Administration, of persons aged eighteen through twenty-one, fully a fifth do not have licenses, totaling 3,335,254, enough to carry several states. At the other end are 4,738,013 persons over seventy-five who no longer have valid licenses. Others are middle-aged women who take public transit to work or get lifts from relatives. Race is also involved: legislators know their black constituents are less likely to be regular drivers.

Thus far ten states, all Republican-controlled, have passed laws demanding government-issued documents. In 2008, the Supreme Court’s conser- vative majority upheld Indiana’s statute, dismissing all arguments about its disparate impacts. And last month, a state judge in Pennsylvania refused to scrutinize its own law, saying it had to follow the Supreme Court. The 2012 election will be conducted under these constrictions.

Florida’s deterrents are not untypical. Like all states, it will issue identity cards for voters in the driver’s license format. Still, trips must be made to a motor vehicle office, a $25 payment is expected, and applicants without passports must locate a birth certificate to validate their identity. Wisconsin won’t charge a fee if the card is only for voting. Still, twenty-two items on a form must be filled out, including boxes for your race, weight, and hair color. At this point, it is still undecided whether a state university ID, with photo, will let resident students cast a ballot. Unsurprisingly, GOP legislators are not sympathetic.

To insist on a government-issued card is a voting tax in another guise, demanding considerable time and exertion to exercise a basic right. Most cynical are legislators who say they only wish to thwart fraud at the polls, since they know full well that “impersonation” went out with Tammany Hall. Except when they have candidates like Eisenhower or Reagan—which they surely don’t this year—Republicans realize that their best prospect for winning is to downsize the electorate, particularly people who have low incomes and are not white. It’s one thing to turn people off by running a boring campaign. It’s quite another to chop whole segments of the citizenry from the electoral rolls.

4.

Mitt Romney and his party begin with two clear advantages, which they hope will compensate for his ambiguous record and less than galvanizing presence. The first is the unprecedented amount of money ready to be spent for his campaign. Hence a recurring question: Can having a financial edge turn an election? It’s not hard to cite cases where it hasn’t. Meg Whitman and Carly Fiorina lost in California in 2010, despite using personal fortunes and hugely outspending their opponents. (True, they were seen as rich newcomers.) So did Linda McMahon in Connecticut in 2010. (She is the Republican nominee for a Connecticut Senate seat again this year.)

The most visible outlays are for television, now supplemented by banners on websites. No one really knows how all these messages are received, let alone ingested. But even if they become background noise, something may stick, especially when they’re entertaining. If polls show most people still oppose the Affordable Care Act, it isn’t because they have mastered the bill (who has?), but because of the slogans and soundbites that have circulated on the air.

Yet even here, it’s been less paid commercials that have been influential than Republicans on television and elsewhere, talking first and loudest. There’s every reason to think that GOP candidates at all levels will have money to burn, far more than Democrats can raise. My own inclination is to focus on Americans themselves, as they watch television and drive by billboards and surf the Internet. They are not exactly cookie dough, to be persuaded by whoever pummels them the most. Overall, the GOP’s stress on taxes and deficits isn’t exactly diverting, and we know that voters viscerally withdraw after too many attacks on opponents. Still and all, this year may tell us whether money can carry the day.

Where money is best spent is for what we once called “retail politics”: locating likely supporters, approaching them doorbell by doorbell, and providing rides to polling places. (And this year, helping them to secure an acceptable identification.) While it’s nice to have money for rental cars, the chief need is for committed workers on the ground, some raising money. Republicans have never been as able to field as many such troops. Perhaps they’re too middle-aged, or ill at ease canvassing in unfamiliar neighborhoods. To be sure, there will be the wherewithal to hire people by the hour to carry the clipboards. Even so, it’s not clear that paid surrogates reading from scripts will win undecided voters over. Obama prevailed in 2008 because of unprecedented local efforts on his behalf, notably by college students, single people, and suburbanites pleased to put placards on their lawns. If much of that enthusiasm has ebbed, it isn’t that many of them are turning toward Romney. Even if fewer of them will be ringing bells, the Democrats’ challenge will be to bestir them to vote.

Where Republicans have another edge is their majority on the Supreme Court. From Bush v. Gore to Citizens United, Republican-appointed justices have not been shy about their partisan leaning. (Unlike others picked by GOP presidents: Earl Warren, David Souter, John Paul Stevens.) Theirs could be the final word if results in key states are close and contested, especially because of turned-away voters. Sadly, there’s little doubt how they’ll decide. After all, they have their own precedent.

This Issue

September 27, 2012

Pride and Prejudice

Cards of Identity

Are Hackers Heroes?

-

1

The others: Hughes–Wilson (1916), Dewey–Roosevelt (1944), Dewey–Truman (1948), Goldwater–Johnson (1964), Dole–Clinton (1996). ↩

-

2

See Ryan Lizza, “Fussbudget: How Paul Ryan Captured the GOP,” The New Yorker, August 6, 2012. ↩

-

3

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Security Watch, June 2012. ↩

-

4

“The Next Election: The Surprising Reality,” The New York Review, August 18, 2011. ↩

-

5

See the many papers presented at the conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Orlando, May 17–20, 2012. ↩

-

6

Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications (Free Press, 1955), p. 345. ↩