When Billie Holiday promised, “the difficult I’ll do right now, the impossible will take a little while,” she admitted that she was “crazy in love.” But that lyric might well serve as the anthem of the gay rights movement, which has achieved, more swiftly than any other individual rights movement in history, not merely the impossible, but the unthinkable. Those who have fought for what might be called the privileges of gay romance—the rights to marry and to have intimate sexual relations with the partner of one’s choosing, regardless of gender—were called crazy, and worse, by many. But with respect to both sodomy and marriage laws, they have proven not foolish romantics, but visionaries.

When Ninia Baehr and Genora Dancel sued the state of Hawaii for the right to marry in 1991, no state, indeed no country, recognized the right of same-sex couples to marry. Gay rights groups at the time opposed the filing, worried that it would create bad law and/or spark anti-gay resentment. Most of the American public, it is safe to say, had hardly considered the issue, precisely because it was unthinkable. At the time, 75 percent of Americans thought gay sexual relations were morally wrong, and only 29 percent thought gays and lesbians should be permitted to adopt children. When, in the early 1980s, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors became the first city council in the country to recognize domestic partnerships, Mayor Dianne Feinstein vetoed the ordinance.

Today, two thirds of Americans, including Rush Limbaugh, support civil unions for same-sex couples; nine states and the District of Columbia have recognized gay marriage; and nine more have recognized same-sex civil unions or domestic partnerships with all or most of the benefits associated with marriage. In the 2012 election, after an unbroken string of losses on popular referenda, gay marriage proponents prevailed on all four state ballot initiatives addressing the issue. Voters in Maryland, Maine, and Washington approved referenda expressly authorizing the recognition of gay marriage, and Minnesota voters rejected an amendment banning gay marriage.

Polls suggest that this progress will continue. A nationwide poll this year by the Public Religion Research Institute found that 62 percent of people between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine favor gay marriage, while only 31 percent of those sixty-five and over do so. Nate Silver, the statistician best known for his FiveThirtyEight blog, who accurately predicted Obama’s victories in both 2008 and 2012, has analyzed demographic data state by state and projected that no later than next year a majority of people in a majority of the states will support gay marriage. By 2016, Silver says, the only states that will still have a majority opposing it will be in the Deep South; and by 2024, a majority will favor gay marriage even in Mississippi, likely to be the last holdout. Widespread recognition of gay marriage is, in the words of Michael Klarman, a professor at Harvard Law School and the author of From the Closet to the Altar, “inevitable.”

But Klarman, one of the country’s leading legal historians, remains skeptical of the utility of litigation to achieve this result. In From the Closet to the Altar, he tells the remarkable story of the legal, political, and cultural struggle over marriage equality. But even as he chronicles the almost unheard-of progress on this issue in the past two decades, Klarman argues that each judicial advance has been met with a forceful political reaction, at substantial cost to gay rights and to liberal causes more generally. The book—and the warning—could not be more timely, as the Supreme Court has announced that it will review two cases this term challenging the constitutionality, respectively, of a federal law and a California constitutional amendment limiting marriage (and related legal benefits) to the union between a man and a woman. Decisions in the cases are expected this summer.1

If Klarman is correct, gay rights proponents should be very nervous, because even a victory in court might well spark a broader public defeat. Klarman’s historical account is comprehensive, trenchant, and provocative. But his case that gay marriage litigation backlash has done more harm than good is not nearly as strong as he implies. In fact, it seems more likely that, by forcing people to “come out” on the issue, the marriage equality lawsuits have advanced the cause of gay rights.

Klarman argues that almost every time a state court has ruled in favor of same-sex marriage, its decision has sparked an adverse reaction that seems to set back the cause, not only of same-sex marriage itself, but of gay rights more broadly. Thus, in 1993, when the Hawaii Supreme Court in the Baehr case became the first state supreme court to rule that a state’s refusal to recognize same-sex marriage might be unconstitutional, Hawaii’s legislature responded by declaring that marriage was limited to the union of a man and woman, and Hawaii’s voters subsequently amended their constitution to ratify that action. In 1996, Republicans introduced in thirty-four state legislatures “defense-of-marriage” bills, banning recognition of same-sex marriages performed in other states. Within two years, twenty-two such laws had been adopted. By 2001, thirty-five states had enacted such laws—even though, at that point, no state yet recognized gay marriage.

Advertisement

Not to be outdone on the homophobia front, in 1996 Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act, which not only allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed by other states, but also denied tax, health, Social Security, and pension benefits for spouses under hundreds of federal laws to same-sex couples married in states that recognize gay marriage, though again, none yet did. The bill passed the House by a vote of 342–67 and the Senate by 85–14. Senator John Kerry was the only senator up for reelection in 1996 to vote against the law. This is the federal law the Supreme Court has agreed to review this term.

Even in Vermont, the only state with a socialist senator, litigation in favor of gay marriage prompted an impassioned political response. In 1999, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that denying marriage to same-sex couples violated its state constitution. A storm of opposition to this ruling ensued. It was quelled only by the Supreme Court’s subsequent decision that “civil unions,” affording same-sex couples all the tangible benefits, but not the status, of marriage, was sufficient to satisfy the constitution. Even that result was controversial. Governor Howard Dean supported the civil unions bill, which a majority of Vermonters opposed, and in his gubernatorial campaign of 2000 saw his lead over his challenger fall twenty percentage points after he signed the bill into law.

When the California Supreme Court declared that the refusal to recognize same-sex marriage violated its state constitution, voters overruled that decision by amending the constitution through Proposition 8. (Lower federal courts declared Proposition 8 unconstitutional, but the Supreme Court has now granted review.) When the Iowa Supreme Court ruled that denying same-sex marriage violated its state constitution, voters responded by unseating three state supreme court justices in the next election. And the backlash wasn’t only sparked by court decisions. When Maine’s legislature adopted gay marriage in 2009, the voters overturned that action by amending the constitution by referendum that same year. This year, Maine voters reversed themselves, legalizing gay marriage in yet another referendum initiative.

But Klarman reserves his harshest criticism for Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, in which the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 2004 became the first state supreme court to require, as a state constitutional matter, the recognition of same-sex marriage. That decision sparked a nationwide response. Within five years, twenty-five states had enacted constitutional amendments banning gay marriage. (Before Goodridge, only three states had done so.) In all of these states, of course, gay marriage was already not recognized, but inscribing that ban into the state’s constitution makes it much more difficult to change.

And the Goodridge decision may have had consequences far beyond gay marriage, according to Klarman. He maintains that because two thirds of Americans were opposed to gay marriage in 2004, this was a dream issue for Republicans, and a nightmare for Democrats. It mobilized and united the Republican base, while driving a wedge between Democrats, who were divided on the issue.

Indeed, Klarman contends, gay marriage may have tipped the 2004 presidential election for President George W. Bush, and in turn affected the composition of the Supreme Court. President Bush won Ohio, which turned out to be the swing state that decided the election, by a 2 percent margin, while an anti–gay marriage referendum there passed by 62–38 percent. Bush’s share of the vote among Ohio’s older voters, voters with only a high school education, religious voters, and black voters all increased from 2000 to 2004 by more than it did nationwide. Significantly, these groups were also disproportionately opposed to gay marriage. Thus, Klarman joins the many commentators who claimed, in the immediate aftermath of the 2004 election, that the gay marriage referendum probably brought out more conservative voters and may well have made the difference. In his second term President Bush then had the opportunity to appoint Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, conservative jurists likely to be hostile to gay rights.

If Klarman is correct that the Goodridge case led to President Bush’s 2004 reelection, this backlash was surely devastating for gay rights generally. In a close election, however, any number of factors can appear to have been “determinative.” And the evidence is in fact far more equivocal than Klarman suggests. Stephen Ansolabehere and Charles Stewart III, political science professors at Harvard and MIT, have argued convincingly that gay marriage did not tip the balance, and if anything, appears to have helped the Democratic challenger John Kerry more than Bush.2 They noted that of the eleven states that had gay marriage referenda, only three were “battleground” states where the outcome was in doubt—Ohio, Michigan, and Oregon—and Kerry won two out of the three. In states where gay marriage was not on the ballot, Bush’s county-by-county share of the average vote increased from 2000 to 2004 by about 3 percent. In states where gay marriage was on the ballot, his average county share of the vote decreased by 2.6 percentage points.

Advertisement

Duke University Professor D. Sunshine Hillygus and University of Arkansas Professor Todd Shields reached similar conclusions. They reviewed a 2004 post-election survey, controlling for demographics, party identification, and ideology, and found that opinions about gay marriage “had no effect on voter decision making among Independents, respondents in battleground states, or even among respondents in states with an anti-gay marriage initiative on the ballot.”3 The issues that most affected voters in 2004, they found, were not gay marriage, but the war in Iraq, the economy, and terrorism.

Nor is there evidence that religious voters played a more significant role in 2004 than in 2000. In both 2000 and 2004, 42 percent of the voters attended church at least once a week. Bush won 63 percent of those voters in 2000 and 64 percent in 2004.4 States with gay marriage on the ballot had less than a one percent higher turnout rate than states without a referendum, and most of that difference is attributable to the fact that three of the states were battleground states, where turnout generally was higher.

At a minimum, then, there is serious doubt about the single most significant incidence of backlash that Klarman identifies. Klarman acknowledges in a sentence that “scholars have reached mixed conclusions” on whether gay marriage cost the Democrats the presidency in 2004, but he discusses none of the evidence contradicting his account. That evidence suggests that it is just as possible that the gay marriage issue helped Kerry.

Even if the Goodridge decision galvanized gay marriage opponents and united the Republicans in the short term, as Klarman argues, those same effects may hurt the Republicans in the medium to long term. Because young people overwhelmingly favor recognition of gay marriage, opposition to its recognition is likely to make the Republican Party less attractive to new voters. President Obama’s explicit endorsement of gay marriage seems to have had no discernible backlash in this year’s election, as young voters again favored Obama by a large margin.

While it is true that gay marriage decisions have in the short term sparked popular indignation and a political response, it is also true that the overall speed of progress on marriage equality is virtually unparalleled in the history of social reform movements. As the columnist Ellen Goodman put it in 2009, “in the glacial scheme of social change, attitudes [about gay marriage] are evolving at whitewater speed.” As Klarman himself notes:

In the years since Goodridge alone, the pace of change has been extraordinary. In 2003–4, Americans opposed gay marriage by roughly two to one. In the summer of 2010, for the first time ever, a national poll showed a majority of Americans supporting gay marriage.

And he acknowledges that the trend has “accelerated dramatically in just the last three years,” that is, in the wake of pro–gay marriage decisions in California and Connecticut in 2008, and the 2009 decision in Iowa. These changes in public opinion are inconceivable without the gay marriage litigation. Those cases made the once unthinkable a reality, exposed the absence of any good reason for denying gay marriage, and thereby spurred social reform on an issue that the ordinary political process would have preferred to ignore. The litigation helped gay marriage “come out.”

After two hundred pages stressing backlash, Klarman grudgingly admits that for the issue of gay marriage itself, the litigation may well have had a net positive effect, but immediately follows that admission with an assertion that it had negative effects for other gay rights and liberal causes. Gay rights groups have diverted resources to gay marriage that Klarman thinks might have been better spent on other battles, such as ending discrimination based on sexual preferences.

But as the discussion of the 2004 election illustrates, once one moves beyond specific effects on gay marriage itself, one enters a field of virtually unbounded speculation. It is entirely possible that the reversal in public attitudes about gay marriage has made the public more open to other gay rights issues, in part because the image of gays and lesbians seeking to formalize their committed monogamous relationships undermines negative stereotypes of homosexuals as irresponsible and licentious.

Klarman’s concern about backlash is not limited to the issue of gay marriage; he argues more generally that court decisions protecting individual rights that do not already enjoy widespread majority support often spark backlashes that do more harm than good to the cause sought to be vindicated. In other writings, he has made this claim about such landmark constitutional victories as Brown v. Board of Education, which he claims made segregation more tenacious at least in the short term; Roe v. Wade, which inspired the growth of the right-to-life movement; Miranda v. Arizona, which protected suspects from abusive interrogation but also, Klarman argues, inspired Richard Nixon’s “war on crime” and the radical expansion of America’s prison population. He also points out that Furman v. Georgia, which invalidated the death penalty (temporarily) in 1972, revived what had been a waning interest in the death penalty, as thirty-five states enacted new capital punishment statutes in response.

Klarman is surely right that judicial decisions protecting unpopular constitutional rights are likely to spur popular resistance—although, as the gay marriage issue illustrates, it is far from clear that such resistance constitutes a net loss for those seeking to protect the right in the first place. The right-to-life movement has been a force to be reckoned with since Roe v. Wade, but it is also true that in the meantime millions of women have enjoyed the security of that right, with its substantial effects on their freedom to plan their lives and enter the workforce. And surely Nixon’s “war on crime” may well have happened without Miranda, as it was at least as much if not more a response to the riots and rising crime rates of the late 1960s and early 1970s, as well as a a strategic ploy to peel off Southern Democrats. If the “war on crime” would have happened anyway, it’s clearly better that suspects being interrogated in police custody be afforded their basic legal rights.

Klarman insists that his book is not intended to “criticize historical actors for failing to behave differently, nor does it seek to draw confident conclusions about how future reform movements should evaluate the trade-offs between litigation and other methods of pursuing social reform.” But it is difficult to read it as anything but a critique of rights litigation. The critique, however, seems misperceived. The very reason we protect certain rights through constitutions that resist revision by majorities is that some rights by their nature are unlikely to be realized through the ordinary political process—particularly the rights of minority groups, unpopular dissidents, or the criminally accused. If we could rely on the ordinary political process to protect such rights, there would be no need for protecting them through judicial enforcement of constitutional principles. But history shows that we cannot.

Precisely because constitutions are needed to safeguard unpopular rights, protection of those rights is likely to spark a popular reaction. We should hardly be surprised by the reactions Klarman describes. But this does not mean that judicial protection of rights is futile, or counterproductive, as he seems to imply. First, there are instances, and the gay marriage cases may be one, where litigation makes reform more, not less, likely. Where one seeks to advance a right that will simply be ignored by the ordinary political process, going to court is often the only way to be heard. Had Ninia Baehr approached the Hawaii legislature to ask it to enact a statute recognizing gay marriage, she would have been dismissed as a nut. The political process can, and in a sense is designed to, ignore the unpopular cause; not so the courts. It is no accident that legislatures did not even begin to recognize gay marriage until 2009, well after several state supreme courts had prepared the way by finding its recognition constitutionally mandated.

In the case of marriage equality, while politicians and many of their constituents were decidedly hostile, the legal argument was very strong. Klarman shows almost no interest in the constitutional law governing this issue. He barely mentions the reasoning the courts use to conclude that same-sex marriage is constitutionally protected, and devotes only a page and a half of his over two-hundred-page book to an anodyne recitation of the constitutional arguments on both sides. His focus is not on the law, but on public opinion, and he argues that judges insulated from political reactions may set off a backlash because they “may occasionally misread public opinion.”

But reading public opinion is not the judges’ job. Their job is to enforce the law, even if, and especially when, public opinion is against it. It was easy for politicians to reflexively reject the idea of gay marriage as contradicting the traditional definition of marriage. But courts subjected the claim to constitutional analysis. And when one tests the refusal to recognize gay marriage against the constitutional mandates that government treat people equally and respect the dignity of their intimate life choices, the legal argument for requiring recognition of gay marriage is compelling. The Supreme Court has ruled that laws disadvantaging gays and lesbians cannot be defended by resort to moral condemnation or mere tradition. So the states are left to make patently unpersuasive claims that recognizing same-sex marriage will undermine opposite-sex marriage, harm children, or reduce procreation. But there is simply no reason to believe that allowing same-sex couples to marry has any negative impact on heterosexuals’ desires to marry or to have or raise children. And gays and lesbians already have and raise children; no state has articulated a good reason to deny them the opportunity to do so within a sanctioned marital relationship.5

Klarman seems to believe that courts should do no more than follow the election returns, and that when they fail to do so, they only cause trouble. But if that were true, there would be little reason to make rights central to constitutions. We do so, both at the national and the state level, because we have long understood that for all its advantages, democracy is not particularly good at protecting the rights of minorities. If courts do their job properly, they will not always reach results that accord with popular opinion. They will sometimes make decisions that result in short-term backlash. But we might well take that as evidence that they are actually performing the function that we expect from them. And as the gay marriage issue illustrates, courts need not be relegated to playing the part of followers when it comes to social change mandated by constitutional principles.

The Supreme Court has many options in deciding the two gay marriage cases that it has agreed to review this term. It could reject the contention that treating same-sex couples and opposite-sex couples differently violates equal protection—a decision that would set back the cause of marriage equality dramatically. It could declare that equality demands recognition of gay marriage on the same terms as opposite-sex marriage, a decision that would have immediate and wide-ranging consequences for the forty-one states that today do not recognize gay marriage. Or, as is most likely, it could decide the cases in a more nuanced manner, invalidating the federal statute because Congress has no good reason for discriminatorily disregarding state laws respecting gay marriage. The court could also invalidate Proposition 8 on technical narrow grounds that do not immediately implicate the marriage laws of other states.

Whatever the Court does in the short term, however, it seems certain that in the not-too-distant future, we will look back on today’s opposition to gay marriage the way we now view opposition to interracial marriage—as a blatant violation of basic constitutional commitments to equality and human dignity. The Supreme Court’s 2013 gay marriage decisions will be viewed either as the Plessy v. Ferguson or the Brown v. Board of Education of gay rights. The choice should be clear.

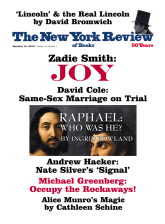

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

1

See my discussion, “Laws Not Fit to Be Defended,” NYRblog, December 8, 2012. ↩

-

2

Stephen Ansolabehere and Charles Stewart III, “Truth in Numbers: Moral Values and the Gay-Marriage Backlash Did Not Help Bush,” Boston Review, February/March 2005. ↩

-

3

D. Sunshine Hillygus and Todd G. Shields, “Moral Issues and Voter Decision Making in the 2004 Presidential Election,” PS: Political Science and Politics, Vol. 38 (April 2005), p. 201. ↩

-

4

Ethel D. Klein, “The Anti-Gay Backlash?,” in The Future of Gay Rights in America, edited by H.N. Hirsch (Routledge, 2005). ↩

-

5

I analyze the legal arguments used in the same-sex marriage cases in detail in “The Same-Sex Future,” The New York Review, July 2, 2009. ↩