One reason I’ve never been a fan of graphic novels is because a central aspect of literature for me has always been imagining what the things I’m reading about look like. I can tell you in great detail about not only the lush Parisian interiors of Jean Des Esseintes—an easy task, what with all the detail Huysmans gives us about the decadent duke’s taste in decor—but also the brave little Chinese-themed party that Carol Kennicott throws to brighten life in drab Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, and the original Homer Simpson’s “queer” Irish–Spanish–New England cottage in LA’s Pinyon Canyon.

Considering my specialization in architecture, I’m not surprised that the first graphic novel to thoroughly engage, not to say captivate, me is Chip Kidd and Dave Taylor’s Batman: Death by Design. It is by turns an impassioned plea for historic preservation, a cautionary tale of engineering hubris, a nostalgic homage to the visionary draftsman Hugh Ferriss (1889–1962), whose futuristic chiaroscuro renderings exalted the skyscraper as the ultimate symbol of burgeoning American might during the interwar years, and an acidic indictment of the present-day cult of architectural stardom.

Based on the enduringly popular comic-book superhero created in 1939 by the artist Bob Kane and the writer Bill Finger, Batman: Death by Design was created by a dynamic duo equally devoted to the Caped Crusader. Kidd, who wrote the story, is a prolific dust-jacket designer and author of Batman Collected (1996) and Bat-Manga!: The Secret History of Batman in Japan (2008) among many other books; Taylor, who did the illustrations, is a British-born comic-book artist who has worked on several Batman projects for DC Comics, including the graphic novella Riddler and the Riddle Factory (1995).

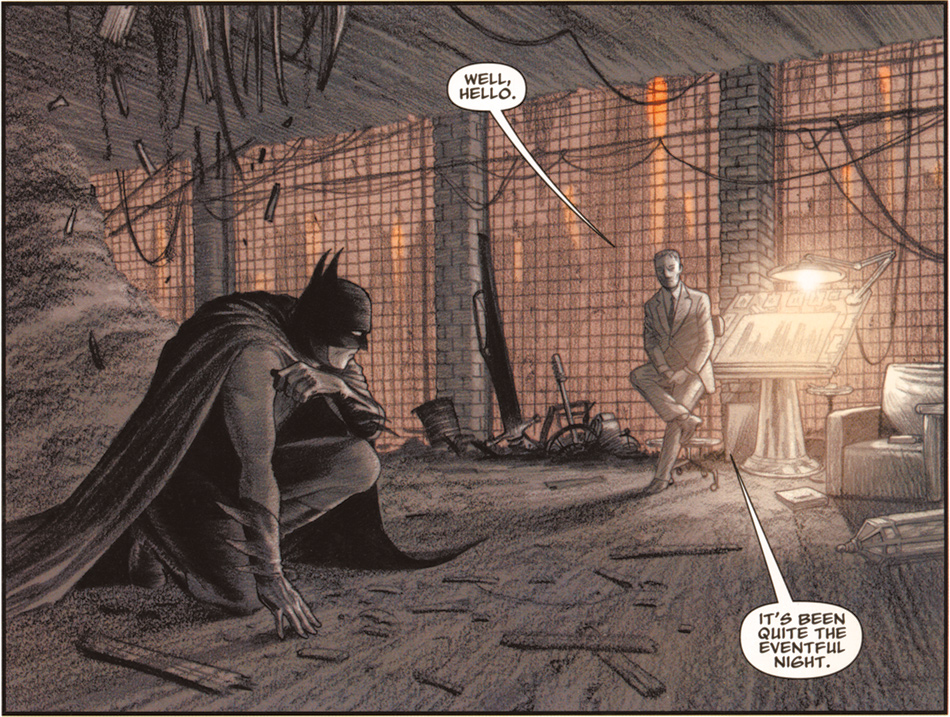

There’s a cinematic sweep to Taylor’s compositions that makes several splash pages seem as capacious as a 70-millimeter theater screen. For their predominant tonality he chooses a warm sepia that has all the subtle gradations and dramatic multiple light sources of film-noir cinematography. The book’s craftily gauged pacing—which varies from crowded multi-panel pages to stunning single-image spreads—proves that all the digital gimmickry and 3-D effects of today’s action-movie franchises pale next to the imaginative powers of a first-rate artist working with pencil in two dimensions.

Kidd’s plot, which takes place in some unspecified period that could be a half-century ago or hence, concerns the impending demolition of a major Gotham City landmark, the Art Decoid Wayne Central Station, a railroad depot that is now crumbling and abandoned. Although it had been shoddily developed by Bruce Wayne’s (aka Batman’s) father, it is an example of “Patri-Monumental Modernism”—an amusing coinage of Kidd’s that hints at the hybrid style’s ambitious and somewhat macho civic grandeur—and preservationists think it is still worthy of salvation.

A complicated series of rather choppy plot twists, which involve, inter alia, the kidnapping of one major character by the Joker, culminates with the rebuilding of Wayne Central Station in a more soundly constructed version of the original design, an implicit endorsement of old architecture over new. The whole story is shrouded with the anachronistic ambiguity (if not the stylistic grotesquerie) of Terry Gilliam’s retro-futurist film fable Brazil (1985).

Among architectural insiders, Batman is likely to cause the most comment for its scathing portrayal of a Netherlandish master builder named Kem Roomhaus, who, as Batman says, “may be an affected, narcissistic creep, but he’s also a genius.” This summation comes perilously close to the privately held opinion of some who have dealt with the extravagantly gifted but notoriously difficult Rem Koolhaas.

To be sure, the megalomaniacal Dutchman drawn by Taylor bears less of a resemblance to the Nosferatu lookalike Koolhaas than to a somewhat chubbier Daniel Libeskind (minus his industrial-strength eyeglass frames). Moreover, the fictional Kem Roomhaus’s scheme to replace Wayne Central Station with “a massive replica of the rib cage of the Megaptera nivaengliae, more commonly known as the humpback whale” is a wicked lampoon of Santiago Calatrava’s carcass-like, $3.8 billion Transportation Hub now under construction at the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan. Yet few design buffs will be in doubt about the prototype for the architectural villain of this piece.

Several other dramatis personae also evoke real figures. The hard-boiled editor of the Gotham Gazette (“cut him, he bleeds ink”) is named Elliot Osbourne, an inversion of Osborn Elliott, editor of Newsweek during its Sixties and Seventies glory years. The book’s sole female character, Cyndia Syl, “a society fixture who has taken up the cause of what she sees as an architectural masterpiece,” is physically a dead ringer for the late socialite and garden-advice columnist C.Z. Guest (she of the snub nose and beautiful-hair-Breck-blond pageboy bob). Syl’s determination to rescue the endangered railway terminal closely parallels Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s second-career star turn as savior of Grand Central Station. And then there’s the subliminal push-and-pull between Syl and Wayne, which seems to resemble the crackling sexual tension between Howard Roark and Dominique Francon in Ayn Rand’s overheated architectural potboiler, The Fountainhead.

Advertisement

At times, Batman: Death by Design brings to mind the fond Moderne fantasies of the writer, illustrator, and futurist Bruce McCall, as in Taylor’s vision of a vertiginous nightclub called the Ceiling, comprised of a vast transparent-glass slab cantilevered high above Gotham City’s streets and described as “reductive design taken to its ultimate extreme, introducing a brand new school of architecture [Roomhaus] calls Mini-Maximalism.” (To which the architect retorts, “No!! It’s Maxi-Minimalism!,” a clear send-up of Koolhaas’s size obsession codified in his thumping 1995 tome S, M, L, XL.) Here Kidd’s dialogue harks back to the snappy banter of B-movies in the Golden Age of Hollywood, as in this exchange at the opening night of the Ceiling:

Reporter: And here’s Bruce Wayne with…Cyndia Syl?! Mr. Wayne! Is there romance in the air?

Wayne: Oh, I….

Syl: Definitely not. You’re smelling the Sterno from the buffet tables. Move along, Junior.

[Frightened when she looks down at the see-through floor, Syl grabs onto Wayne]

Syl: …Sorry about that.

Wayne: Oh, no trouble. Hope I didn’t get any Sterno on you.

Syl: Let’s sit. Before I yawn in Technicolor.

As Kidd’s epigraph explains, “The inspiration for this story came from two real-world events: the demolition of the original Pennsylvania Station in 1963, and the fatal construction crane collapses in midtown Manhattan of 2008.” The book’s juxtaposition of intentional and accidental architectural destruction implies that there is little difference between them in their harmful effect on civic culture.

Batman: Death by Design is as intriguingly multilayered as the metropolis it depicts. One of the most arresting pages pairs up-and-down, day-and-night views of the imperiled Central Station’s interior that are likely informed by Berenice Abbott’s incomparable 1936 black-and-white photos of the long-lost Penn Station concourse, a soaring, sun-dappled space in which the boldly exposed but gracefully wrought steel structure conveyed all the grandeur of Classical architecture. In one panel, Syl reminds Wayne of his father’s motivation in building such an awe-inducing marvel: “You must astonish them.”