A curious thing about the United States is that anticommunism has always been far louder and more potent than communism. Unlike sister parties in France, Italy, India, and elsewhere, the Communist Party here has never controlled a major city or region, or even elected a single member to the national legislature. Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party in 1948 received no more than 2.4 percent of the popular vote with Communist support; and Wallace himself soon repudiated the Communists here and abroad.

American anticommunism, by contrast, built and destroyed thousands of careers; witch-hunted dissidents in Hollywood, universities, and government departments; and was a force that politicians like Joseph McCarthy and Richard Nixon rode to great prominence. Of course this was not the first time that heresy hunters have overshadowed the actual heretics: consider the Inquisition, which began before Martin Luther, the greatest heretic, was even born, or how, on accusations of Trotskyism, Stalin imprisoned or shot Soviets by the millions—numbers many times those of Trotsky’s beleaguered, faction-ridden actual followers. But heresy hunting is seldom really about ideas; it’s about maintaining power.

Power begins with surveillance, and the pioneer in American anti-Communist surveillance was Ralph Van Deman, whose elongated hawklike face made him someone a movie director would have cast for the job. A career US Army officer, Van Deman first made his mark keeping a close eye on Filipinos who might have the temerity to resist the long occupation of their country that began with the Spanish-American War. As the military intelligence chief in Manila starting in 1901, he used a web of undercover agents and the newest record-keeping technology—file cards—to track thousands of potential dissidents.

Later in his career, back in the United States, Van Deman filled his cards with the names of American socialists, labor activists, and supporters of the Russian Revolution, the sort of people rounded up in the notorious Palmer Raids of 1919–1920 that jailed some ten thousand leftists. He continued collecting information about Communists and other left-wingers long after he retired as a major general in 1929. With funding from the Army and J. Edgar Hoover’s new Federal Bureau of Investigation, he maintained a private network of informants until his death in 1952, keeping his 250,000 file cards in his house in San Diego, where they were frequently consulted by police Red squads and the FBI.1

It was Hoover, of course, who would take Van Deman’s search for real or imagined Communists to far greater heights. More than forty years after his death, we know a great deal about this unpleasant and power-hungry man, but the California investigative journalist Seth Rosenfeld adds significantly more in Subversives, which is based on some 300,000 pages of FBI documents, pried out of the resistant agency over more than two decades in a series of Freedom of Information Act lawsuits.

The papers largely concern FBI surveillance, disinformation, and other monkey business during the student revolts that roiled the University of California at Berkeley in the 1960s. These upheavals made Berkeley surely the only college campus in the world with four full-time daily newspaper correspondents stationed on it, and for a while, as a greenhorn reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, I was one of them. I watched firsthand the mass arrest of 773 Free Speech Movement sit-in demonstrators in December 1964 for demanding an end to restrictions on political speaking and organizing on campus, the massive marches and teach-ins against the Vietnam War over the following several years,2 and the astonishing sight of a California National Guard helicopter swooping across the campus in 1969 indiscriminately spraying a dense white cloud of tear gas.

I thought I knew all that was going on, but it turns out there was much that none of us knew, from the fact that the FBI secretly jammed the walkie-talkies of monitors directing a huge 1965 anti-war march I covered to the agency’s decade-long vendetta against Clark Kerr, the man who was first chancellor at Berkeley and then president of the University of California system.

Everyone knew that the FBI had no love for student leftists, but Hoover’s intense hatred for Kerr is the major revelation of Rosenfeld’s careful and thorough book—and it was a revelation for Kerr as well when Rosenfeld shared some of this material with him shortly before Kerr died in 2003. “I know Kerr is no good,” Hoover scrawled in the margin of one bureau document.

Although Kerr was largely reviled by the activists of the Free Speech Movement, who were—quite rightly—protesting his university’s ban against political advocacy on campus, he was far more than the colorless bureaucrat he appeared. For one thing, he had a wry sense of humor, at one point quipping that the real purpose of a university was to provide sex for the students, sports for the alumni, and parking for the faculty. More importantly, he was a man of principle. From 1949 to 1951, for example, the university was riven by a fierce controversy over a loyalty oath required of all employees. More than sixty professors refused to sign, and thirty-one of them, as well as many other staff, were fired. Though a staunch anti-Communist, Kerr spoke out strongly against the firings and the witch-hunt atmosphere surrounding them. His stands on such matters won him the enmity of right-wingers, and he was soon on Hoover’s radar.

Advertisement

The heresy that Hoover feared most was not communism; it was threats to the power of the FBI. And so what pushed him over the line from hostility to absolute rage at Kerr was an exam question. University of California applicants had to take an English aptitude test, which included a choice of one of twelve topics for a five-hundred-word essay. In 1959, one topic was: “What are the dangers to a democracy of a national police organization, like the FBI, which operates secretly and is unresponsive to criticism?”

In response, a furious Hoover issued a blizzard of orders: one FBI official drafted a letter of protest for the national commander of the American Legion to sign; other agents mobilized statements of outrage from the Hearst newspapers, the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, and the International Association of Chiefs of Police. An FBI man went to see California Governor Edmund G. Brown and stood by while Brown dictated a letter ordering an inquiry into who wrote the essay question.

Hoover himself wrote to members of the university’s board of regents, who swiftly apologized. But his ire did not subside; he ordered an FBI investigation of the university as a whole, assigning an astounding thirty employees to the task. The result was a sixty-page report, covering professorial transgressions that ranged from giving birth to an illegitimate child to writing a play that “defamed Chiang Kai-shek.” The report also noted that seventy-two university faculty, students, and employees were on the bureau’s “Security Index.” This was the list Hoover kept of people who, in case of emergency, were to be arrested and placed in preventive detention, as in the good old days of the Palmer Raids. Like Hoover’s forebear Van Deman, the FBI maintained the index on file cards, but now these were machine-sorted IBM cards.

One of Rosenfeld’s finds is that when the FBI didn’t have another weapon handy, it sent poison-pen letters. The man initially suspected of writing the offending essay question, for instance, was a quiet UCLA English professor and Antioch College graduate, Everett L. Jones. When intensive sleuthing couldn’t find anything to tie Jones to the Communist Party—the usual FBI means of tarring an enemy—someone in the bureau wrote an anonymous letter on plain stationery to UCLA’s chancellor, signed merely “Antioch—Class of ’38,” saying that the writer had known Jones and his wife in college, where “they expressed views which shocked many of their friends,” and later became “fanatical adherents to communism.”

Hoover’s anger at Clark Kerr was reignited in 1960, when thirty-one Berkeley students were among those arrested in a large demonstration against a hearing by the House Un-American Activities Committee in San Francisco’s City Hall—an early landmark in what would be a tumultuous era of American student protest. Hoover was outraged when Kerr refused to discipline the students taking part. Kerr said, reasonably enough, that any student demonstrators were acting as private individuals and “were not in any way representing the university.”

The upheavals of the Free Speech Movement, which had Berkeley in turmoil during the 1964–1965 school year, and of the protests against the Vietnam War that began shaking the campus soon after, brought renewed scrutiny by the FBI. As always, Hoover’s anticommunism had little to do with the Soviets: although the FBI’s responsibilities include counterespionage, only twenty-five of the three hundred agents in Northern California were assigned to this, while forty-three were at work monitoring “subversives,” which meant people like student activists at Berkeley—and, it turns out, even some of those they thought were their enemies, like the university’s regents.

Hoover gathered information about several liberal pro-Kerr regents and funneled it and other ammunition to a major enemy of Kerr, regent Edwin Pauley, a wealthy Los Angeles oilman. An FBI official then reported back to Hoover that an appreciative Pauley could be a useful informant and could “use his influence to curtail, harass and…eliminate communists and ultra-liberal members on the faculty.”

The balance on the board of regents changed following Ronald Reagan’s election as California governor in 1966 (the governor and several other state officials are ex officio regents), and at Reagan’s first meeting, Kerr was fired. Even though Hoover can’t be blamed for Kerr losing his job, he had already made sure that there was another one the educator didn’t get. Some months earlier, President Johnson had decided he wanted Kerr to be the next secretary of health, education, and welfare. “I’ve looked from the Pacific to the Atlantic and from Mexico to Canada,” LBJ told Kerr in his famous arm-twisting mode, “and you’re the man I want.” Kerr said he would think it over. Meanwhile, Johnson ordered the usual FBI background check. Among the documents Rosenfeld wrested from the agency in his legal battle is the twelve-page report Hoover sent the president. Included in it were allegations from a California state legislative Red-hunter who claimed that someone named Louis Hicks had worked with Kerr in the 1940s and declared that Kerr was “pro-Communist.”

Advertisement

“Hoover’s report failed to note, however,” Rosenfeld writes, “that when FBI agents interviewed Hicks he denied making the charge.” The report made a string of similar misrepresentations, among them another such charge—with no mention of the FBI investigation that found it untrue. Before Kerr could tell LBJ that he had decided to turn down the post, the president withdrew the offer.

Hoover’s FBI did its best not only to wreck the careers of enemies like Kerr, but to promote those of its friends, like Ronald Reagan. Although Rosenfeld far overstates the bureau’s influence on Reagan’s rise, it is nonetheless jarring to see how much help he got from an agency that was supposed to stay above partisan politics. Reagan had been trading information with the FBI about alleged Communists and radicals ever since his days as president of the Screen Actors Guild in the 1940s, and he continued to feed the bureau Hollywood political gossip for long afterward. The FBI did various work for him in return, for example investigating whether a live-in boyfriend of his estranged daughter Maureen was already married (he was).

Another FBI favor for Reagan also concerned a wayward child: his son Michael. In 1965, after Hoover had at last, reluctantly and under much pressure, finally begun investigating organized crime, an agent reported that “the son of Ronald Reagan was associating with” the son of Mafia clan chief Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno. Both sons enjoyed pursuing girls and driving fast cars, and the young Bonanno already had a police record at eighteen. The routine procedure would have been for FBI agents to interview Reagan for any information about the Bonannos he might have learned, but Hoover ordered instead that the agents should simply suggest to Reagan that he tell Michael to find another companion. Reagan, just then gearing up for his first run for governor, was most grateful.

The FBI provided him many other courtesies over the years: a personal briefing from Hoover, data for his speeches, quiet investigations of people the University of California was thinking about hiring—even though screening applicants for jobs that didn’t have to do with the federal government was outside the bureau’s jurisdiction. But Hoover’s biggest favor of all for Reagan was something he didn’t do. In 1960, an informer the agency thought was “reliable” reported that Reagan secretly belonged to the John Birch Society—an organization even the FBI thought so extreme (it considered President Eisenhower a Communist) that it was kept under surveillance. Rosenfeld says that he could not tell from the available records whether this claim was true. But, he notes, “it was precisely the kind of uncorroborated information” that the bureau had quietly slipped to dozens of politicians or journalists over the years when it wanted to damage the reputation of someone like Clark Kerr. This report—which could easily have wrecked Reagan’s future political career—Hoover kept quiet.

One appeal of hunting alleged heretics is that it is relatively easy. By contrast, good police work—chasing down corporate crime or the Mafia, for instance—is extremely hard. Small wonder that in building the power of the FBI, Hoover preferred the first to the second. But what happens to a professional anti-Communist when, on the home front anyway, there are almost no more Communists? Rosenfeld’s book is in part a portrait of an FBI clumsily looking for new targets. In a curious echo of the hostility the Soviets and their satellite regimes had toward the anti-authoritarian overtones of rock music, Hoover grew alarmed about the counterculture. Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters came into his sights, as did organizations like Berkeley’s Sexual Freedom League.

But the world was shifting under the FBI’s feet. In the old days, of course, if you couldn’t wreck someone’s career by tying him to a known Communist, you could still do so by exposing a sexual misdeed. Or you could simply hint that you had such information—a method Hoover for decades used to blackmail potential congressional critics into silence. But even though the bureau dispatched a poison-pen letter in 1965 to reveal that a prominent Berkeley antiwar activist had fathered a child out of wedlock, the FBI’s Northern California chief wrote Hoover sadly that such leaks were no longer so effective. These student radicals, he explained, “do not have the same moral standards as a Bureau employee.” In such treacherously changing times, what was a poor blackmailer to do?

Although Subversives is perhaps one hundred pages too long (we don’t need to know a Free Speech Movement leader’s grades in each college course, for example), Rosenfeld’s many years of digging have produced other notable revelations. The most controversial concerns Richard Aoki, a military veteran and particularly confrontational student leader in the later stages of Berkeley 1960s activism—at one point he urged his comrades to steal weapons from National Guard armories. Aoki also provided guns to Black Panther Party members and gave them some of their first weapons training. When his book was first published, Rosenfeld startled just about everyone, it seems, by showing that Aoki was an FBI informant. This accusation has generated a furious fusillade in Aoki’s defense in the pages of the Chronicle of Higher Education and other publications. But in my reading of both sides, the charge seems well documented and convincing; moreover, when Rosenfeld asked him directly if he was an informer, Aoki gave a vague and ambiguous answer.

Aoki’s defenders do not believe that so charismatic a leader could have been anything other than the passionate fighter for justice he appeared. Yet in the murky world of surveillance and double agents, some people can serve two masters. Perhaps the most famous such figure was Yevno Azev (1869–1918), for a decade and a half the key informer for the tsarist secret police, on whose behalf he infiltrated the Russian revolutionary movement and betrayed hundreds of his comrades. But while leaking the details of some assassination plots to the authorities, he nonetheless zestfully helped plan others, including the murder of a provincial governor, of the Grand Duke Sergei (the tsar’s uncle), and of the minister of the interior. It appears that neither Azev nor his alarmed police handlers ever figured out which side he was really on. Was that true for Richard Aoki?3 We will never know: ill with kidney disease, he committed suicide four years ago.

Aoki’s record raises the question: Was the Black Panther Party’s descent into criminal violence mainly the work of FBI agents provocateurs? Were more undercover agents whom we don’t yet know about responsible for the move toward violent confrontation, also beginning around 1969, by other groups, such as the Weather Underground?

I think not. Even though new information about FBI manipulation may eventually surface, there was already plenty of madness in the air by end of the 1960s. The trail of Black Panther extortion, beatings, murders, and other crimes—especially in Northern California—is so long as to be far beyond the FBI’s ability to create it. And by 1970, there were also too many white leftists who romanticized third-world revolutionaries, talked tough, wore military fatigues, and spoke a different language than the nonviolent one of the Free Speech Movement leaders of 1964–1965.

The principal activists of that movement knew their fight was a universal one. They cared about civil liberties from Mississippi (where FSM leader Mario Savio had been a civil rights worker) to Moscow (a year after their own mass arrest, FSM veterans held a Berkeley campus rally for imprisoned Soviet dissidents Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel). But political generations were short-lived in the 1960s, and by a few years later, some of the fatigue-clad solidarity activists who passed through Eastern Europe en route to North Vietnam showed little concern over the Soviet-bloc invasion that had crushed the Prague Spring of 1968.

Rosenfeld rightly appreciates the best of the Free Speech Movement leaders, especially the late Mario Savio, whom I came to know toward the end of his life: a gentle, eloquent, deeply intelligent man whose passion for civil liberties and social justice had the strength of a religion. Even though Savio’s lifelong battle with depression and keen belief that the movement could not thrive if it were centered on him personally led him to stay in the background after 1965, it did not prevent the FBI from following his every move, monitoring his bank account, and aggressively questioning his neighbors, employers, friends, and landlords.

Even at its worst, the FBI was far less draconian than dozens of secret police forces active around the world then and today. Poison-pen letters are one thing; disappearances, torture, and murder another. But changes in technology have vastly increased the ease of surveillance. In the 1950s, Rosenfeld reports, in order to eavesdrop on a meeting in Jessica Mitford’s house, two bumbling FBI agents hid in a crawl space beneath it; the mission almost came to grief when one fell asleep and started snoring. But today those agents would have access to vastly more: not just Mitford’s phone calls—which they were already tapping—but her credit card statements, her Google searches, her air travel itineraries, her bookstore purchases, her e-mails, her text messages, her minute-by-minute locations as signaled by the GPS in her mobile phone. To hold longtime records of this sort on whomever it chooses to monitor, the National Security Agency is building in Bluffdale, Utah, for $2 billion, the largest intelligence data storage facility on earth—five times the size of the Capitol building in Washington. It is scheduled to open later this year.4

Naturally, it’s all in the name of stopping terrorism, but the misuse of intelligence-gathering for political purposes, from Ralph Van Deman and the Palmer Raids to J. Edgar Hoover and his meddling with a university board of regents, should make us aware that such things can happen again. The combination of electronic data collection, a vague and nebulous foreign threat, and tens of billions of dollars pouring into “homeland security” each year is a toxic mix, ripe for new demagogues. Subversives is a timely warning. That essay question on the 1959 University of California entrance exam is one we must never stop asking.

This Issue

May 23, 2013

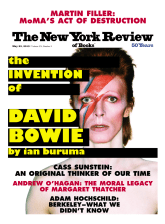

MoMA’s Act of Destruction

An Original Thinker

Maggie

-

1

For Van Deman’s story, see Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press, 2009). ↩

-

2

This was enough to gain a notation in my own FBI files, which I obtained under the Freedom of Information Act years ago, that “acting as a representative of the press,” I had been in contact with the march organizers. Although I was a very small fish indeed, my FBI and CIA files from the 1960s run to more than one hundred pages. ↩

-

3

He and Azev apparently both had personal motives for some of their actions: J. Edgar Hoover, surprisingly, had opposed the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans that had placed Aoki in a prison camp as a child, and Vyacheslav von Plehve, the minister of the interior whose assassination was plotted by Azev, a Jew, had orchestrated a series of pogroms. ↩

-

4

See James Bamford, “The NSA Is Building the Country’s Biggest Spy Center (Watch What You Say),” Wired, March 15, 2012. ↩