One morning in mid-May I drove to Manouba University, the largest in Tunisia, to meet Habib Kazdaghli, the dean of the Faculty of Letters and one of the most prominent critics—and victims—of a campaign by Salafist radicals to Islamize the country. An avuncular man with a shock of white hair and a trim gray mustache, Kazdaghli is a secular scholar of ethnic minorities in Tunisia who has fought to keep religion out of university affairs. He received me in his office, which he had fortified with extra locks. “In the current atmosphere, I have to be careful,” he told me.

Kazdaghli’s troubles began during the first days of the academic year two years ago. A Salafist and former student at Manouba named Mohammed Bakhti—who had been released from prison in January 2011, after serving six years of a twelve-year sentence for jihadism—confronted Kazdaghli in his office. He demanded that women be permitted to wear the face covering known as the niqab in class. “I told him, ‘The niqab cannot be permitted, I need to see the students I’m dealing with,’” Kazdaghli said. That, however, seems only part of the explanation. Kazdaghli, a former member of Tunisia’s Communist Party, has made no secret of his antipathy toward the Islamists; he also believes that capitulating to the religious extremists on one issue would open the university up to other demands, and radically change its secular nature.

Days later, fifty Salafists invaded the campus and held a sit-in outside the dean’s office. “I had to climb over mattresses to get in and out,” Kazdaghli said. Besides the niqab, the extremists demanded an on-campus prayer room for students, segregated faculty rooms, and separate classes for men and women. Kazdaghli refused, saying that he opposed gender segregation and was unwilling to give up one of his already overcrowded classrooms for religious purposes. Salafist protesters then overran the university during exam period and occupied it for a month, causing thousands of students to miss their tests.

The confrontations grew uglier. In March 2012, two niqab-wearing women forced their way into Kazdaghli’s office, knocked the files off his desk, and threatened to burn the place down. “I called the police and they said, ‘We can’t get involved. The prosecutor has to give the order,’” he told me. Kazdaghli eventually persuaded the women to leave his office, but when one tried to come back inside, the dean pushed her out and slammed the door behind her. On March 6, two hundred Salafists surrounded the university, demanding the dean’s expulsion. One climbed up the flagpole, tore down the Tunisian flag, and raised a jihadist banner in its place. Kazdaghli, whose specialty is Tunisia’s near-vanished Jewish community, was accused on TV by Salafists of being “a Mossad agent,” then hauled before a court in Tunis to face charges of assault filed by one of the women students. He has made ten appearances before a magistrate in the last ten months.

Kazdaghli was bitter about his treatment by the government. The police and prosecutors had failed to come to his aid several times, he told me, and Ennahda—the self-described “moderate” Islamist movement banned by the Ben Ali dictatorship that now heads the ruling coalition—had remained silent throughout the Salafist siege. “Of all the political parties in Tunisia, Ennahda was the only one that said nothing,” he told me. Late last year, Mohammed Bakhti, the Salafist who made the initial set of demands, died in prison after an eight-week hunger strike following his arrest for participation in the September 2012 attack on the US embassy in Tunis. The Salafists have moved on to other causes, though they have vowed to press their demands on Kazdaghli and the university in the future. Meanwhile, university classes continue.

For most of the last two years, Tunisia seemed to have more workable politics than the other nations caught up in the Arab Spring. In a country noted for being among the most liberal in the Arab world—where liquor flows freely and the beaches are filled with scantily clad sunbathers—Ennahda, the Islamist party that won 41 percent of the vote in the October 2011 elections, immediately tried to reassure secular democrats by pursuing a policy of moderation. Ennahda formed a coalition with two centrist secular parties, and blocked attempts by hard-liners to write sharia law into a new constitution. “After one and one half years of Ennahda, what has changed?” Rachid Ghannouchi, the movement’s seventy-two-year-old spiritual leader, asked me when I met him at his headquarters in Tunis. “The mosques are open, the bars are open, the beaches are open. People are free to choose their way of life.”

Advertisement

But the tensions here are escalating. In the past several months, there have been regular confrontations between Salafists—the ultraconservative Islamists who have also been a strong force in Libya, Egypt, Yemen, and other countries—and police and soldiers across the country. Tunisian Salafists have traveled to Syria to fight with the Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaeda- affiliated Islamic rebel group now battling the army of Bashar al-Assad and his Hezbollah allies. The Salafists returned to Tunisia committed to jihad. In early May a small band of Tunisian militants began attacking the Tunisian security forces at the Jebel ech Chambi, a five-thousand-foot mountain in a remote and rugged region near the Algerian border, a tactic ominously reminiscent of jihadist violence in the Algerian and Malian deserts.

The Ennahda-led government, which initially seemed to ignore the Salafists and may even have collaborated with them, seems more willing to address the threat they pose. “What we are seeing now is completely new for us,” I was told by Kamel Morjane, Tunisia’s foreign minister during the last of the Ben Ali years. “We don’t know where it’s going to lead.” Morjane resigned his post two weeks after Ben Ali’s fall and two months later he created a secular party, al-Moubadara, or the Initiative, which has embraced some of the liberal social policies of the country’s first president, Habib Bourguiba, and called for clean government.

Despite his affiliation with the dictatorship, Morjane was never tainted by allegations of corruption and won respect after he swiftly condemned the military in December 2010 for opening fire on protesters. But his party’s poll ratings are low, and Morjane could find himself excluded from politics if the drafters of the new constitution approve an article, still being debated, eliminating all former members of the ancien régime.

The rise of the Salafists in Tunisia is connected with the excesses of the dictatorship. President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who ruled Tunisia from 1987 until 2011, effectively declared war on conservative Islam. Ben Ali’s security police sometimes arrested women who wore hijabs in public, and closely monitored mosques and the schools of Islamic learning known as madrasas. They locked up 25,000 Islamists, and often tortured them. As in Egypt, many of them grew increasingly radicalized during their long years in prison. (Ghannouchi was among five thousand Ennahda members who fled the country just ahead of Ben Ali’s 1991 dragnet; he lived as an exile in London for twenty years.)

In the first chaotic days after Ben Ali’s flight to Saudi Arabia in January 2011, ten thousand people walked out of Tunisia’s prisons. These included common criminals who escaped, and political prisoners—among them three thousand Salafists—liberated by the Ministry of Justice. Emboldened by the rebellions in Libya and Egypt, the group took advantage of the collapse of security to take to the streets. They protested outside synagogues and stormed movie theaters. In September 2012 they attacked the US embassy and burned down an adjacent American school, destroying ten thousand library books and causing $5.5 million worth of damage.

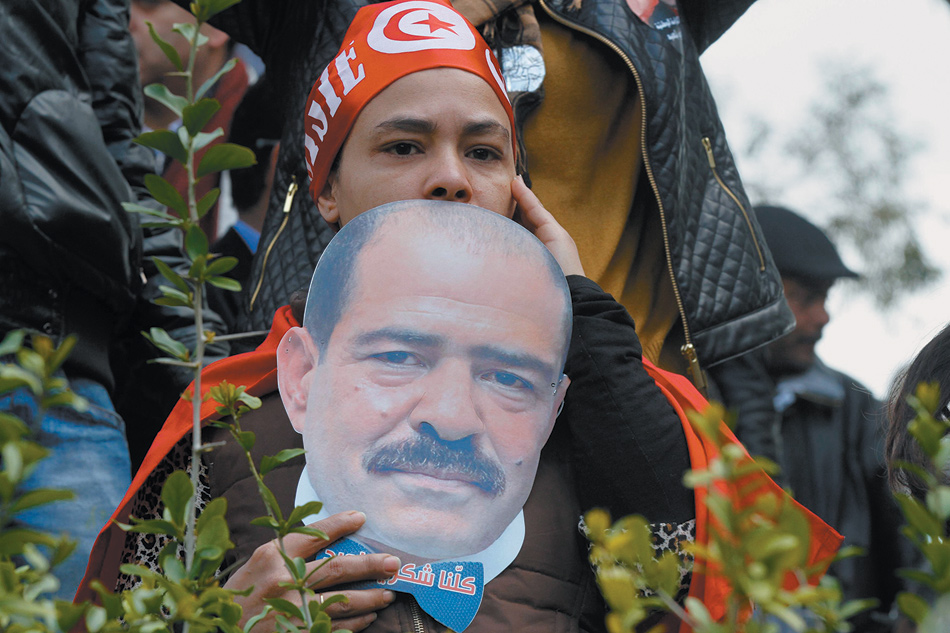

Sufis, with their emphasis on mysticism and saint worship, are particular enemies of the Salafists, who have firebombed or defaced at least forty Sufi Islamic shrines during the last year, including the mausoleum of Sidi Bou Said, a thirteenth-century mystic buried in the much-visited hilltop suburb that bears his name. Salafists have also been accused of carrying out the worst act of political violence since the revolution, the assassination on February 6, 2013, of Chokri Belaïd, a human rights lawyer and leader of a leftist party, who was gunned down at point-blank range while sitting in his car in front of his house in Tunis. The killing set off the biggest street protests in Tunisia since the 2011 overthrow of Ben Ali.

Many secular democrats still distrust Ghannouchi, accusing him of tacitly encouraging the ultraconservatives. Last year Ghannouchi’s opponents released a secretly made video of the Ennahda leader addressing a meeting of Salafists. Ghannouchi spoke of them as his “sons and daughters” and encouraged them not to lose sight of their goal of Islamizing the country. “We should open Koranic schools and reopen the mosque of El-Zaytouna,” he said, referring to a network of now-shut-down madrasas established around one of the country’s oldest mosques, in the medina of Tunis. Ghannouchi told me his remarks had been taken out of context. “It made it sound like there was a secret pact between us,” he said. “I didn’t tell them to pick up weapons and build training camps.”

Morjane, the former foreign minister, made it clear that he blamed the jihadists’ guerrilla campaign on the slack response of Ennahda. “What is happening in Chambi today you could not think of happening during the time of Ben Ali,” he told me. Ghannouchi insisted that the government was taking a hard line. “In the attack against the US embassy, the security forces killed four or five of them, and they arrested over eighty of them, and when they tried to smuggle weapons from Libya, three of them were killed,” he said. “What do we need to do to convince people that we are against extremists? Do we need to adopt the Ben Ali policy of opening concentration camps and putting thousands of people inside?”

Advertisement

The al-Fatah mosque, a single-story structure of pink marble topped by a green tile roof, just off the Avenue de la Liberté in downtown Tunis, is a good place to consider the strength of the radicals. Constructed several decades ago with Saudi Arabian money, the mosque has become, in the last two years, a meeting place for adherents of Ansar al-Sharia, the most vocal and violent Salafist group in Tunisia.

The mosque served as the refuge for the fugitive leader of the Tunisian Salafists, Seif Allah Ibn Hussein, also known as Abu Iyadh, who is wanted by police for inciting the attack on the US embassy. He is now believed to be fighting against the army on the Jebel ech Chambi mountain.

In February 2011 several hundred Salafists gathered here and marched to the nearby Grand Synagogue, waving Islamist banners and chanting anti-Semitic slogans. “Wait, wait, Jews, the Army of Mohammed is returning,” they shouted, before police and local people broke up the protest. About 1,500 Jews still live in Tunisia, including five hundred in Tunis and a thousand on the island of Djerba, and they were left unmolested under the Ben Ali regime; the Grand Synagogue typically attracts between twenty-five and thirty people to Sabbath services. I was told by Jews that most of them still feel safe in Tunisia, despite anti-Semitic rhetoric from the Salafists and efforts by some hard-liners in government to criminalize all contact with Israel.

In a plaza beside the mosque I encountered a burly vendor of jihadist flags who identified himself only as Yassin. He had a thick black beard, Ray-Ban sunglasses, and long, curly black hair that flowed from beneath his tan Taliban-style cap. Yassin had appeared in the news in March 2012, when photographers snapped pictures of him tearing down the Tunisian flag in front of Manouba University and replacing it with a black jihadist banner. Now, he told me, he was getting ready for another potentially violent confrontation: a large gathering of Salafists scheduled for the following Sunday in Kairouan, the Islamic cultural capital of Tunisia, a hundred miles south of Tunis. The Tunisian government had refused to give the group a permit and threatened to arrest anyone who showed up, but Yassin said that the Salafists would not be dissuaded. “Ansar al-Sharia does not want to ask for any authorization, because we don’t recognize the ones who are giving the authorizations,” he told me.

Yassin wore a black T-shirt emblazoned with jihadist imagery: on the front, a map of Syria with a Kalashnikov- carrying fighter from the Jabhat al-Nusra, the radical Islamic rebel group in Syria that has recruited many fighters from Tunisia; on the back, a portrait of Osama bin Laden accompanied by the legend “Jihad Is Not a Crime.” A picture of the World Trade Center, with a jet about to strike, adorned his shoulder. It suggested the Adidas logo, but instead of “Adidas,” it read “alqaïda.” “The police threw me in jail for wearing my T-shirt, and held me for four days,” he told me, grinning. “But they had to let me go, because there is no law against defending my views.” What were those views? “Al-Qaeda represents Islam, and al-Qaeda defends Islam,” he replied. Despite the incendiary messages on his T-shirt, Yassin insisted that he had entered a pacifist phase. “I’m doing dawaa, making people aware of their religious obligations,” he told me. “I’m not killing people.”

After leaving the mosque, I drove to Menzah, a middle-class neighborhood north of downtown Tunis. In the parking lot of a run-down, nine-story apartment building off a quiet road lined with pine and eucalyptus trees, I was shown a small memorial with candles and scrawled messages for Chokri Belaïd, the outspoken critic of the Islamists who had been killed here three months earlier. Belaïd had a strong following among the country’s miners, dockworkers, and other laborers. Although his party had won only 2 percent of the vote in the October 2011 election, he had since won the support of the country’s powerful trade union association and was putting together a coalition of left-wing parties called the Popular Front.

Some political analysts predicted that a Belaïd-led coalition could have won 10 to 15 percent of the vote in the next parliamentary election. He was often seen on Tunisia’s television talk shows and news broadcasts during the past year, attacking the Islamists and warning about the creeping religious transformation of the country. At eight o’clock in the morning on February 6, Belaïd left his building and stepped into the passenger seat of a car that was waiting for him; an assailant emerged from behind a hedge, shot him through the window four times, then sped away on a motorcycle.

Police swiftly arrested four suspects, all of them Salafists in their thirties and forties, and claimed that they had identified the triggerman as Kamel Gathgathi, reportedly once a student in the United States, who is believed to have fled abroad. The interior minister, Lotfi Ben Jeddou, said the suspects belong to an “Islamist cell” that had set out to murder prominent secular politicians. But according to Abdel Majid Belaïd, the murdered man’s older brother, the government’s theory didn’t make sense. “Belaïd always said that the Salafists were not out to get him, that it was Ennahda who had motive to kill him,” he told me. “They were political rivals.” A few days earlier, an investigating judge in the case had summoned for questioning a top Ennahda official based in Paris who had been seen lurking around Belaïd’s apartment building three months before he was killed. “We all know that Ennahda is not one,” said Morjane, the former Ben Ali foreign minister. “It is clear that they have their hard-liners.”

Ghannouchi denied any involvement: Islamic radicals, he told me, “want to destabilize the situation by assassinating an opponent of Ennahda…. They are even accusing me of personally being behind the murder. And because of this I’ve taken a few people to court.”

But many people remain skeptical. In front of the Ministry of the Interior building on the Avenue Bourguiba, the site of anti–Ben Ali protests during the revolution, I came across several hundred supporters of Belaïd who were commemorating the one-hundred-day anniversary of his assassination. The protesters carried placards in French, English, and Arabic that read “Who killed Chokri?” and chanted, “Ghannouchi killed Belaïd.” “Ennahda is involved in the killing,” a speaker from Belaïd’s party told the crowd. “This is the counterrevolution, and we want the government to say the truth.”

Before I left Tunisia in May, the relationship between the Salafists and Ennahda seemed to be growing more contentious. Nine members of security forces were injured by land mines during a sweep around the Jebel ech Chambi, which turned up sixteen arms caches and materials for making explosives. Meanwhile, on Sunday, May 19, the government responded strongly to Ansar al-Sharia’s vow to bring 40,000 followers to its annual congress in Kairouan, where they planned to rally around the city’s seventh-century Grand Mosque and call for sharia law. Tunisia’s prime minister, Ali Larayedh, a member of Ennahda, declared that the gathering was a “threat to public order” and announced that no permits would be allowed. Police and soldiers were deployed across the country, taking up positions on highways, exit ramps, and the streets of Kairouan. Ansar al-Sharia told its members to meet instead in the poor Tunis suburb of Ettadhamen, a Salafist stronghold, and in the clashes that followed, one Salafist died, eighteen were injured, and two hundred were arrested. Among those picked up in the fighting by security forces, I later learned, was Yassin—the burly jihadist wearing the black al-Qaeda T-shirt whom I had met at the al-Fatah Mosque. He was now in a Tunis jail, a comrade said, and “We don’t know when they will let him out.”

The courts also seemed to have turned against the Salafists. At the university, Habib Kazdaghli was acquitted of the assault charge; the two Salafist women who had burst into his office more than a year ago were convicted of trespassing. “I think that the tide has turned against the extremists,” he told me. But in his office in downtown Tunis, Rachid Ghannouchi said that he had little sympathy for Kazdaghli. “He is a Marxist, and they don’t believe in the right of people to practice their religion,” he said, making reference to the dean’s one-time membership in the Communist Party. “He is refusing to find a compromise.” That may, however, be just posturing. Ennahda’s popularity is dropping in the polls, largely both because of its failure to deal decisively with Salafist violence and because of Tunisia’s stagnant economy; some political analysts say that the Islamists could get as little as 30 percent of the popular vote in the election, down from 41 percent in October 2011.

Ennahda’s weakened position may force it to align itself further with the secular Democrats—it now dominates a coalition known as the “troika” with two centrist parties—and also to distance itself decisively from the Salafists. “There is a split taking place with Ennahda now,” I was told by a political observer who knows Ghannouchi well. “The hard-liners are being pushed aside.” If these trends continue, and it is far from sure that they will, the surge of Islamic extremism that has shaken the country for the last two years may have the effect of moving Tunisia toward a path of moderation.

—June 13, 2013

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

Hard on Obama

The Unbearable