Any scholar visiting the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia quails before the huge Marianne Moore archive—poems, drafts, letters, reading notebooks, conversation notebooks, poetry notebooks, postcards, clippings, and little objects (not to speak of her grandfather’s large furniture). The museum says on its website:

The Rosenbach has a long and important relationship with the modernist poet Marianne Moore (1887–1972). In the late 1960s, the museum purchased from Moore virtually all of her manuscripts and correspondence. When she bequeathed her personal belongings to the Rosenbach, the living room of her Greenwich Village apartment was recreated in the museum as a permanent installation.

In spite of the intimidating quantity of the collection (including more than 30,000 letters), writers on Moore have courageously undertaken to construct the outlines of her life and work, with varying degrees of attention to the life and the poetry. It is simply not possible to compile an exhaustive account of either, let alone of both. Linda Leavell, a professor emerita at Oklahoma State University, has chosen, in her new and revelatory biography, to focus mainly on Moore’s family life, in part because she has gained access to new sources. This is the first biography authorized by Moore’s nieces, who allowed Leavell to read a hitherto unseen “cache of letters about Moore’s father.” (Leavell’s more specialized earlier book on Moore and the visual arts focused on Moore’s literary and artistic networks in New York.)

Charles Molesworth’s critical biography, Marianne Moore: A Literary Life (1990), is more comprehensive on both the literary life and the poetry than Leavell’s new volume, but it is less personal and anecdotal in its emphasis. Leavell’s remarks on the poems are—as Moore might say with her characteristic double negative—“not unhelpful”: they point out the main theme of a poem, trace it to a person it may be describing, or mention the event that occasioned the poem in question, but they do not equal the longer accounts of the poems in Molesworth, or the penetrating analyses in the most convincing book yet to appear on Moore’s poetry, Bonnie Costello’s Imaginary Possessions (1981). One must take Leavell’s offering as yet another tile in the Moore mosaic, valuable for its rendering in detail both the extreme pathos and the dreadful pathology of two generations of the Moore household.

Moore’s father, John Moore, son of the owner of a foundry, left engineering school after one year, married, and within a few years went insane. His wife, Mary Warner Moore, after bearing him a son (John Warner, called “Warner” in the family) and after enduring her husband’s deep depression and unemployment, left him, returning, pregnant with her second child, to her father’s Presbyterian manse. Marianne was born in the manse; there were no further children. Though John’s brother Enos housed him for a while, John, possessed by religious mania, after a short time left the job available to him in his father’s foundry, and never worked again. Enos eventually committed him to the state asylum in Athens, Georgia, where he was diagnosed with “‘delusional monomania,’ his delusion being ‘that he is appointed to find the truths of the Bible.’” Two years after the separation from his wife, John cut off his right hand: “The patient took literally Matthew 5:30: ‘And if thy right hand offend thee, cut it off.’”

Although he was discharged, and lived with his brother for thirteen years, he was then recommitted for “mania on moral and religious matters,” remaining in confinement until his death in the asylum sixteen years later. Marianne never knew her father, and before her old age never spoke of him; William Carlos Williams wrote in a letter that Moore’s father was “indefinite! maybe skipped, maybe dead—never mentioned.”

Mary Warner Moore stayed on in her father’s parsonage for the last seven years of his life, going to live then with her cousin Henry, who died within two years. With her children in tow, Mary moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, near her cousin Mary, and found a position as a high school teacher of English at the Metzger Institute. Warner finished Dickinson Preparatory School and went off to Yale, while Marianne, after graduating from her mother’s school, went to Bryn Mawr. She was prepared for Bryn Mawr’s exacting entrance examinations by her mother’s friend Mary Jackson Norcross (daughter of the Presbyterian minister in Carlisle) and it was to Norcross, rather than to her mother, that Marianne wrote when she fell ill from homesickness in her first year at Bryn Mawr. Norcross was in fact Mary Warner Moore’s lesbian lover: when they became lovers in 1900, Mary Warner Moore was thirty-eight and Mary Jackson Norcross was twenty-five. And Marianne was thirteen.

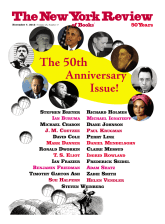

Advertisement

The few surviving letters between Mary Moore and Mary Norcross “leave little doubt about the physical nature of their relationship,” says Leavell. In 1904, Norcross writes to Mary Moore:

Think of having each other at night and all through the day for a whole month, Darling! I’ve never been so starved before. How I long to hold you in my arms and feel your precious self against me.

And in another letter she wishes that Marianne (“Sissy”) had a separate room of her own when the women vacationed together on Monhegan Island: “You see how greedy doing without makes me,” she wrote. In 1910 Norcross left Mary Moore for another woman, her cousin Letty. Mary Moore felt sorrow not merely for her own suffering, but also for Norcross’s distress, writing to the twenty-two-year-old Marianne:

How do you think I feel when I suddenly come upon her and see her knotting her hands together looking into space, her face strained and attenuated, and the tears rolling down her cheeks like rain on a window?

And though Marianne, at twenty-three, was offered a job as assistant to the librarian of the Columbia School of Philanthropy, she turned it down and came home to live for the rest of her life with her mother. Her brother Warner was trained as a minister at the Princeton Theological Seminary, and his mother’s fantasy was that she and Marianne would move into his manse and be a family together once more. In fact they did, for a brief time, live with him at his parish in Chatham, New Jersey.

Warner, however, fled to become a Navy chaplain, but except when he was posted in Samoa, Mary and Marianne contrived to visit him at ports domestic and foreign. Warner’s engagement to the gifted (and rich) Constance Eustis in 1918 caused a crisis in family relations. The intense jealousy of Mary Moore toward her son’s fiancée caused her to write to Constance, two weeks before the wedding, a bizarre letter, disapproving of the marriage without offering reasons (perhaps she suspected that Constance had engaged in premarital sex with Warner; their first child was born less than nine months after the wedding). Warner’s mother wrote:

I feel that his making you an offer of marriage is unethical in a high degree…. It is because I have felt this to be a marriage unblessed of heaven—that I have been unable to enter into the new love that has arisen, and that I resist it as I do.

After the marriage, many of Warner’s letters to Mary and Marianne were mailed without his wife’s knowledge, just as he concealed from his wife the frequency of his visits to his mother and sister. (His wife, jealous of his mother and sister, eventually forbade him to see them except in her presence.)

The family life of the Moores—Mary, Warner, and Marianne—famously consisted of their incessantly writing letters to each other (Marianne once wrote from Bryn Mawr a 150-page description of a four-day visit to a friend, 50 pages of it describing the play she had seen). The thousands of circulating letters (Mary to Marianne, Marianne adding her own and posting the double letter to Warner, Warner adding his own and posting back to Mary) are in themselves peculiar in their frequency, length, and adventitious detail, but even more peculiar is the trio’s intense adoption, from 1914 on, of names from Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, names by which Mary becomes “Mole” (the stay-at-home), Marianne is “Rat” (the writer), and Warner is “Badger.”

In the letters Marianne (as Rat) is usually referred to by both her mother and her brother (and sometimes by herself) as “he” (although her mother, “Mole,” equally male in Kenneth Grahame’s fiction, is not given a male pronoun in the letters). Mary writes to Warner, for instance, of Marianne’s departure for a summer job after graduating from Bryn Mawr:

He looks worse than ever I’ve seen him…. He is overwrought all the time. If it were not for the healthfulness and joy of our home life he would be a nervous wreck.

(The reader of this biography will raise an eyebrow at the idea that the home life in the Moore household was full of health and joy.) Although Mary Moore saw little good in men, she oddly enough turned her daughter into a male figure who became increasingly trapped (or, in her mother’s interpretation, protected) at home. In spite of Marianne’s firm—indeed relentless—intention to become a poet, she returned after Bryn Mawr to a life in Carlisle ordered by her intensely religious mother: she “practiced with the Oratorio twice a week, served as treasurer for the Home Missionary Society, and agreed temporarily to teach a Sunday-school class.” Later, Marianne taught for three years at the Indian School in Carlisle, but she did not move out of her mother’s house, even though she was desperate to write and frustrated by the lack of privacy at home. (Leavell reveals that mother and daughter slept in the same bed until Mary died: at that point Marianne was sixty.)

Advertisement

Tethered to her mother, Marianne became, as her lesbian friend Bryher said, “a case of arrested emotional development.” When, in 1918, Mary and Marianne moved (because Warner was a minister nearby) to an unnecessarily cheap basement studio apartment in Greenwich Village, “the single room could barely contain a bed, a sofa, and a few chairs”:

There was no kitchen, no telephone, no refrigerator. Mary prepared meals on a hotplate in the bathroom throughout the eleven years they lived there. For the first five, before they rented a second room upstairs, they sat on the edge of the bathtub to eat.

(Mary had a small inherited private income from mortgages and real estate, but her frugality was obsessive.) In these close quarters, Marianne’s mother—a monologist according to accounts by visitors—would interrupt her daughter constantly, as Marianne’s letters show; she also read and commented on everything Marianne wrote, giving out caustic opinions (“This is puerile”) when she did not like what she saw.

One particular note of lunacy in the family was the fiction—no doubt created by Mary herself—that she was weak and ill, and needed to be cared for by her children. She was not only “Mole” but also “Fawn,” a child needing protection from the possibility of an early decline. (In the event, she lived to be eighty-four.) Marianne had first published poems in 1915, and by the time she and her dependent and tyrannical mother moved to New York, Ezra Pound had recommended her work to Harriet Monroe, the editor of Poetry, and also to T.S. Eliot. Both Pound and Eliot had reviewed Alfred Kreymborg’s 1917 anthology of poets contributing to Others, his small avant-garde journal; both (with no personal acquaintance with Moore) singled out her thirteen poems there as the manifestation of a new talent. Pound defined her work as “logopoeia or poetry that is akin to nothing but language, which is a dance of the intelligence among words and ideas,” and Eliot described her as among those who could “write living English.”

In 1920, Eliot joined with Moore’s wealthy friend Bryher (the partner of the poet Hilda Doolittle) to surprise Moore by bringing out, in London, a volume of her work called Poems (1921). (Marianne, under the influence of her mother’s disparaging remarks, had not felt ready to publish a volume.) Several poems in that first book became famous, among them Moore’s witty account in “England” of British condescension to American life and art:

…and America…

where cigars are smoked

on the

street in the north; where

there are no proof-readers,

no silk-worms, no

digressions;

the wild man’s land; grass-less,

links-less, language-less

country—in which letters are

written

not in Spanish, not in Greek, not in Latin, not in shorthand

but in plain American which cats and dogs can read!

At the close of “England,” Moore dryly remarks of the achievements of other, supposedly “superior,” European and Asian cultures:

the flower and fruit of all

that noted superiority—should one not have

stumbled upon it in America,

must one imagine

that it is not there? It has

never been confined to

one locality.

What could have pleased the expatriates Pound and Eliot more than this defense of the worth of American culture?

In 1924, the Dial Press—a branch of the avant-garde journal The Dial—published Moore’s wholly original Observations, which revised Poems (1921), not only deleting from it and adding to it but also changing individual poems. (Moore’s Observations now ranks in the annals of modern American poetry with Wallace Stevens’s 1923 Harmonium.) Moore was taken up by poets and artists who soon perceived her wit, her encyclopedic store of information, her radical practice of syllabic but rhymed stanzas, and her cleverness with metaphor. (Kreymborg called her “the enfant terrible of all New York.”)

Moore flourished in the company of fellow poets, counting William Carlos Williams and E.E. Cummings as close friends, but admiring neither so greatly as she admired Wallace Stevens (who later also became a friend). But she was still at home with her mother, supporting herself by a half-time job in the Public Library. (And her mother remained frighteningly tenacious: in a letter to Warner, she once “confronted him with the charge that he was a separate person, but that she and her daughter are not.” A 1946 photograph of mother and daughter by Cecil Beaton shows Marianne in her usual mannish attire, looking wanly depressed, and behind her—and eerily resembling her—her expressionless mother.

In 1925, when she was thirty-eight, Moore was offered the acting editorship (soon to become the editorship) of The Dial, to which she had already submitted poems and essays. The journal was founded and supported by two well-off friends, James Watson (who became a medical doctor) and Scofield Thayer (who eventually became seriously mentally ill). During the four years that Moore was the brilliant editor of the ever-interesting journal, she wrote no poems, confining herself to reviews and to unsigned essays (under the heading “Comment”). When the journal’s founders ceased to fund it in 1929, Moore lost not only a position of literary power but also her enlivening social activities within the New York artistic world.

As that connection with the avant-garde diminished, the influence of Moore’s mother grew stronger, and the conviction that poetry should occupy itself not with satirical observation (Moore’s strong point) but rather with praise began to dominate her poems, making them works of reason rather than of the imagination. Almost all critics agree that her poetry declines over time—but the decline might equally well be ascribed to a fatigue of the imagination of the sort suffered by other poets in later years.

Moore’s impertinent, derisive, sardonic impulses—so evident in many of the early poems (“To Be Liked by You Would Be a Calamity”) show up far less frequently in the later work. The early Moore can utter this scathing comment to a woman bent on verbally attacking someone: the woman is, all by herself, a force that can freeze and tear and disable and draw blood:

your eyes, flowers of ice

And

Snow sown by tearing winds on

the cordage of disabled ships:

your raised hand

An ambiguous signature:

your cheeks, those rosettes

Of blood on the stone floors

of French chateaux, with

regard to which the guides

are so affirmative…

Mrs. Moore remarked icily of Marianne’s conversations with Scofield Thayer, “There is no one I think that they did not vivisect—who ever held a pen.”

Although Marianne frequently incorporated her mother’s sayings into a poem, her mother’s overmastering religious sensibility was not her own. Though she continued to attend church with her mother, and although the Bible is ever-present in her mind, she does not express particular religious convictions. Her poems affirm an ethics without ecclesiastical doctrine. She accepts her mother’s remark that “the power of the visible is the invisible,” but her invisible world is a human one, not an eternal one. In “To Statecraft Embalmed,” she praises “life’s faulty excellence,” accepting life’s distance from religious perfection. Contemplating a white New England church, the pitch of whose spire is “not true,” Moore conceives of a better use of the church than sermons and ritual. (She adds a comic aside about senators and presidents; her ethics has no legal doctrine, either):

The church portico has

four fluted

columns, each a single piece

of stone, made

modester by white-wash. This

would be a fit haven for

waifs, children, animals, prisoners,

and presidents who have

repaid

sin-drivensenators by not thinking about them.

Moore’s mother became crazier with time. In 1923, when Moore was thirty-five, a neighbor gave the Moores a stray kitten whom they named Buffy—and Moore was deeply fond of kittens. After a month, her mother murdered the kitten with chloroform and discarded the corpse off the Hudson River pier (where she and Marianne used to sit on Sundays and read). She had somehow coerced Marianne into agreeing to this act, and we know about it only from a letter by Marianne to Warner (not included in the Selected Letters):

Mole got chloroform and a little box and prepared everything and did it while I was at the library Monday, and nothing could have been more exact…. But it’s a knife in my heart, he was so affecting and scrupulous in his little scratchings and his attention to our requirements of him.

A confused passage about her mother’s reasons (none convincing) ends with her own sense that the act was wrong: “But having had him so long as we had made the deed seem foul.” “I never speak of Buffy to Rat,” said Mrs. Moore to Warner a month later; “his [i.e., Marianne’s] grief drove me frantic.” Four years later Mrs. Moore mentioned to her son that she and Marianne never went to their pier any longer.

And yet Moore stayed with her mother, in the same lodging, in the same bed, year after year, both of them taking to their bed alternately with a series of colds, bronchitis, and other afflictions (small wonder, given their starved diet; one year they had leftover sardines for Thanksgiving dinner). One senses a mutual psychosomatic hysteria. (Hart Crane once referred to Moore, who had revised poems he had submitted to The Dial, as a “hysterical virgin.”) Almost anything could provoke hysteria. When Warner, already a minister, was about to buy a car, “Mole” went into a decline; since Jesus could minister to others without a car, why could not Warner? Marianne wrote her brother that he was driving their mother to illness:

Disappointment makes wreckage of Mole, and she takes things so acutely that she will never, not in any case, live a very long time…. I didn’t know which way to look when Mole was speaking of the automobile. She seemed to sicken and pale so…. It would seem morbid to you perhaps to think that Mole could get sick again because you thought of getting a car but…it isn’t so unreasonable, for Mole would wish to think that without a suggestion from anyone, you ought to know just what is unsuitable.

Yet just as feminists have argued that Dickinson cannily stayed home so that she could write, rather than performing the community chores expected from spinster daughters—helping in illness, engaging in charitable works, being lent out to care for children—so one could argue that Moore found protection in staying with her mother. Her mother cooked (badly) and did the housework, and it was on her income (eventually supplemented by Warner) that they lived. Although Moore enjoyed editing The Dial, during the years of her editorship she wrote no poems: and had she had to support herself, she might never have been able to write. She had been a frail adolescent, and nowadays we would probably classify her self-starving as anorexia; at one point, after the move to Greenwich Village, she weighed only seventy-five pounds. There were moments when Moore could have escaped, but she turned down such opportunities as came her way. She was never known to fall in love, have an affair, or contemplate marriage. Her mother, by playing the orphan child, by turning Marianne into a male (“he”), and by sleeping with her, had in effect made Marianne the man of the house. And the hovering protectiveness of Warner and Marianne confirmed this folie à trois.

As Leavell and other commentators have argued, it was Bryn Mawr, by giving Marianne four years away from her mother, that enabled her birth as a poet. She may have had arrested emotional development, but her intellectual development went up, during those years, by leaps and bounds. She read incessantly, attended lectures and concerts, made friends, went about socially, and became used to the company of intelligent and high-spirited girls and women who were very different from her intelligent (but religiously perverse) mother. Bryn Mawr prepared her to become what she was at her happiest—an arresting member of the New York social scene of artists and writers. Her wit was appreciated, her poems valued by Eliot and Pound and Williams and Stevens. Her editorial selectivity made her conspicuous in judgment, and although she was sometimes patronized (Williams called her “our saint”) she was never thought insignificant.

She will be remembered for her best poems, in some of which (“Marriage,” “An Octopus”) she attains, in part by her juxtaposition of odd quotations, impressive and captivating breadth. In the best shorter lyrics (“A Grave,” “England,” “Sojourn in the Whale,” “The Fish,” “In the Days of Prismatic Color,” “When I Buy Pictures,” and many more) she has an utterly idiosyncratic way of describing both human emotion and exotic flora and fauna. Contemplating the soaring frigate bird, for instance, she is reminded of Handel, and in picturing him, pictures herself:

As impassioned Handel—

meant for a lawyer and a

masculine German domestic

career—clandestinely studied

the harpsichord

and never was known to have

fallen in love,

the unconfiding frigate-

bird hides

in the height and in the majestic

display of his art.

The frigate bird, for all his soaring, must sleep; but at dawn he joins his flock in rising, and despite the effort of his strenuous flying, cures by his majestic art the danger of exhaustion and sorrow:

But he, and others, soon

rise from the bough and though

flying, are able to foil the tired

moment of danger that lays

on heart and lungs the

weight of the python that

crushes to powder.

Works of art (Moore said in “When I Buy Pictures”) “must be ‘lit with piercing glances into the life of things.’” Her poems are “lit with piercing glances” into her own life and that of others. She was, first to last, a misfit, an eccentric, one of those “odd women” so named by George Gissing. Her poem about herself as misfit is called “The Monkey Puzzle”—the familiar name for the bizarre knotted pine tree Araucaria imbricata, native to Chile. Its closing line says everything about Moore’s soul and life, as she puzzled over how she ever emerged, in her own peculiarity, from her father’s insanity and her mother’s religious fanaticism:

This porcupine-quilled,

complicated starkness—

this is beauty—“a certain

proportion in the skeleton

which gives the best results.”

One is at a loss, however, to know

why it should be here,

in this morose part of the earth—

to account for its origin at all;

but we prove, we do not explain

our birth.

Although the techniques of Moore’s verse—the quotations, the syllabic stanza shapes, the persistence of rhyme in free verse, the counterpointing of colloquial speech with counted meter—have been both investigated and praised, her piercing glances into the difficulty of living have not as yet been fully interpreted.

After her mother’s death in 1947, Moore waned as a poet, and she at least suspected that fact. She “appreciated the honesty of a reviewer [of her 1951 Collected Poems] who said that ‘the war poems are embarrassing, and he shudders to think what I may be in old age if my present sentimentality grows on me.’” (The reviewer was the English poet Roy Fuller, and he spoke as a fellow writer.) Although still capable of a good poem, Moore was socially almost a different person, turning into the public eccentric wearing a black tricorne and a black cape, throwing out the first ball at a Dodgers game. The public liked Moore as a celebrity, and the intellectual world liked her as a poet: she received sixteen honorary degrees and many prizes, from the Bollingen to the Pulitzer. But as Yeats wrote in a late letter, “Even the greatest men are owls, scarecrows, by the time their fame has come.”

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust