1.

One September night, running home from dinner to meet a babysitter, I took off my heels and hopped barefoot—it was raining—up Crosby Street, and so home. Hepatitis, I thought. Hep-a-ti-tis. I reached my building bedraggled, looking like death. The doorman—who’d complimented me on my way out—blushed and looked down at his smart phone. In the lobby, on a side table, sat a forlorn little hard-backed book. The World’s Masterpieces: Italian Painting. Published in 1939, not quite thirty pages long, with cheap marbled endpapers and a fond inscription in German: Meinem lieben Schuler…. Someone gave this book to someone else in Mount Carmel (the Israeli mountains? the school in the Bronx?) on March 2, 1946.

The handwriting suggested old age. Whoever wrote this inscription was dead now; whoever received the book no longer wanted it. I took the unloved thing to the fifteenth floor, in the hope of learning something of Italian masterpieces. Truthfully I would much rather have been on my iPhone, scrolling through e-mail. That’s what I’d been doing most nights since I bought the phone, six months earlier. But now here was this book, like an accusation. E-mail or Italian masterpieces?

As I squinted through a scrim of vodka, a stately historical process passed me by: Cimabue, Giotto, Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo, Raphael, Michelangelo. Dates of birth and death, poorly reprinted images, dull unimpeachable facts. (“The fifteenth century brought many changes to Italy, and these changes were reflected in the work of her artists.”) Each man more “accurate” with his brush than the last, more inclined to let in “reality” (ugly peasants, simple landscapes). Madonnas held their nipples out for ravenous babies and Venice was examined from many different angles. Jesus kissed Judas. Spring was allegorized. The conclusion: “Many changes had taken place in Italian art since the days of the great primitive, Cimabue. The Renaissance had opened the way for realism and, at last, for truth as we find it in nature.”

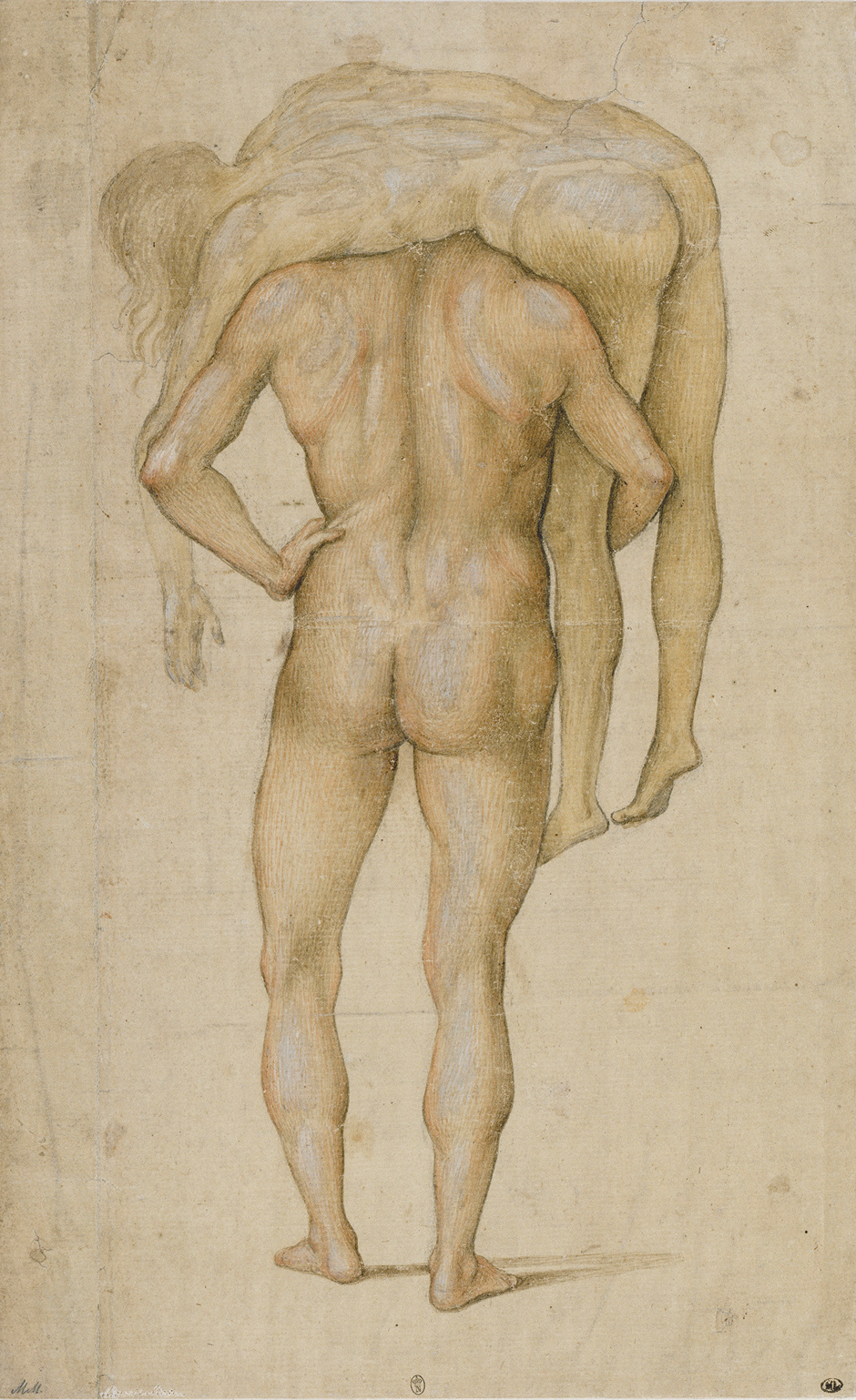

To any reader of 2013 the works of 1939 may seem innocent. Though how jaded, how “knowing” we can think ourselves without knowing much of anything at all. I’ve worked my way through surveys like this before, and am still no closer to remembering who came first, Fra Angelico or Fra Filippo. My mind does not easily accept stately historical processions. But golden yellows and eggshell blues, silken folds of red and green, bell towers and lines of spruce, the penises and vaginas of infants (which, for the first time in my relationship with Italian masterpieces, I am able to judge on their veracity), the looks that pass between the Madonna and her son—these are the sort of things my mind accepts. And I was making my way through these details pleasantly enough when I was stopped short—snagged—by a drawing in charcoal. The whole stately historical procession dispersed. There was only this: Man Carrying Corpse on His Shoulders by Luca Signorelli (circa 1450–1523).

Man is naked, with a hand on his left hip, and an ideal back in which every muscle is delineated. His buttocks are vigorous, monumental, like Michelangelo’s David. (“Undoubtedly indebted to the works of Luca Signorelli.”) He walks forcefully, leading with his left foot, and over his shoulders hangs a corpse—male or female, it’s not clear. To secure it Man has hooked one of his own rippling arms around the corpse’s stringy leg. He is carrying this corpse off somewhere, away from the viewer; they are about to march clean out the frame. I stared at this drawing, attempting a thought experiment, failing. Then I picked up a pen and wrote, in the margins of the page, most of what you have read up to this point. A simple experiment—more of a challenge, really. I tried to identify with the corpse.

Imagine being a corpse. Not the experience of being a corpse—clearly being a corpse is the end of all experience. I mean: imagine this drawing represents an absolute certainty about you, namely, that you will one day be a corpse. Perhaps this is very easy. You are a brutal rationalist, harboring no illusions about the nature of existence. I am, a friend once explained, a “sentimental humanist.” Not only does my imagination quail at the prospect of imagining myself a corpse, even my eyes cannot be faithful to the corpse for long, drawn back instead to the monumental vigor. To the back and buttocks, the calves, the arms. Across the chasms of gender, color, history, and muscle definition, I am the man and the man is me. Oh, I can very easily imagine carrying a corpse! See myself hulking it some distance, down a highway or through a wasteland, before unloading it, surprised at its ever-increasing stiffness, at the way it remains frozen in an L-shape, as if sitting up to attention. And it’s child’s play to hear a neck bone crack as I lay the corpse—a little too forcefully—upon the ground.

Advertisement

Imagining that reality—in which everybody (except me) becomes a corpse—presents no difficulties whatsoever. Like most people in New York City, I daily expect to find myself walking the West Side Highway with nothing but a shopping cart stacked with bottled water, a flashlight, and a dead loved one on my back, seeking a suitable site for burial. The postapocalyptic scenario—the future in which everyone’s a corpse (except you)—must be, at this point, one of the most thoroughly imagined fictions of the age.

Walking corpses—zombies—follow us everywhere, through novels, television, cinema. Back in the real world, ordinary citizens turn survivalist, ready to scale a mountain of corpses if it means enduring. Either way, death is what happens to everyone else. By contrast, the future in which I am dead is not a future at all. It has no reality. If it did—if I truly believed that being a corpse was not only a possible future but my only guaranteed future—I’d do all kinds of things differently. I’d get rid of my iPhone, for starters. Lead a different sort of life.

What is a corpse? It’s what they piled up by the hundreds when the Rana Plaza collapsed in Bangladesh this April. It’s what lands on the ground each time a human being jumps off the Foxconn building in China’s high-tech iPhone manufacturing complex. (Twenty-one have died since 2010.) They spring flower-like in budded clusters whenever a bomb goes off in the marketplaces of Iraq and Afghanistan. A corpse is what individual angry, armed Americans sometimes make of each other for strangely underwhelming reasons: because they got fired, or a girl didn’t love them back, or nobody at their school understands them. Sometimes—horrifyingly—it’s what happens to one of “our own,” and usually cancer has done it, or a car, at which moment we rightly commit ourselves to shunning the very concept of the “corpse,” choosing instead to celebrate and insist upon the reality of a once-living person who, though “dearly departed,” is never reduced to matter alone.

It’s argued that the gap between this local care and distant indifference is a natural instinct. Natural or not, the indifference grows, until we approach a point at which the conceptual gap between the local and the distant corpse is almost as large as the one that exists between the living and the dead. Raising children alerts you to this most fundamental of “first principles.” Up/down. Black/white. Rich/poor. Alive/dead. When an Anglo-American child looks at the world she sees many strange divisions. Oddest of all is the unequal distribution of corpses. We seem to come from a land where people, generally speaking, live. But those other people (often brown, often poor) come from a death-dealing place. What a misfortune to have been born in such a place! Why did they choose it? Not an unusual thought for a child. What’s bizarre is how many of us harbor something similar, deep inside our naked selves.

A persistent problem for artists: How can I insist upon the reality of death, for others, and for myself? This is not mere existentialist noodling (though it can surely be that, too). It’s a part of what art is here to imagine for us and with us. (I’m a sentimental humanist: I believe art is here to help, even if the help is painful—especially then.) Elsewhere, death is rarely seriously imagined or even discussed—unless some young man in Silicon Valley is working on permanently eradicating it. Yet a world in which no one, from policymakers to adolescents, can imagine themselves as abject corpses—a world consisting only of thrusting, vigorous men walking boldly out of frame—will surely prove a demented and difficult place in which to live. A world of illusion.

Historically, the drift from representation toward abstraction has been expressed—by those artists willing to verbalize intent—as the rejection of illusion. From a 1943 mini-manifesto sent by Mark Rothko to The New York Times: “We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.” But what is “truth”?

There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject matter is crucial and that only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.

Death, for Rothko, was the truth—the tragic and timeless thing—and it’s hard not to read his career as an inexorable journey toward it. His 1942 Omen of the Eagle (inspired by the Oresteia—itself an agonized consideration of three corpses: Agamemnon’s, Cassandra’s, and Clytemnestra’s) is the painting that apparently led to the letter, and it’s clearly transitional, still depicting, within Rothko’s famous strata, some recognizable forms: Greek tragic masks, bird heads, many surrealist feet.

Advertisement

By the time of the Rothko Chapel (he killed himself before its unveiling), the strata have emptied out—not only of forms, but of color, too. With those black-on-black, death-dealing rectangles (he found them a “torment” to produce), Rothko was explicitly aiming for “something you don’t want to look at.” Which is one way of accounting for their emotional power: like memento mori, they lead us to an intolerable, yet necessary place.

Rothko wanted us deeply affected by the thing we don’t want to look at. But there exists another solution to our tendency toward illusion: affectlessness. Make the viewer feel like a corpse. For when images proliferate among themselves, as if running mechanically with no human involvement, the viewer will find he lacks a natural point of entry. Simulacra seem to run without us, as the world will continue to run without us, once we are gone. Meanwhile, the idea of the artist—and the viewer—as human subjects, capable of deep feeling, of “torment,” grows obscure.

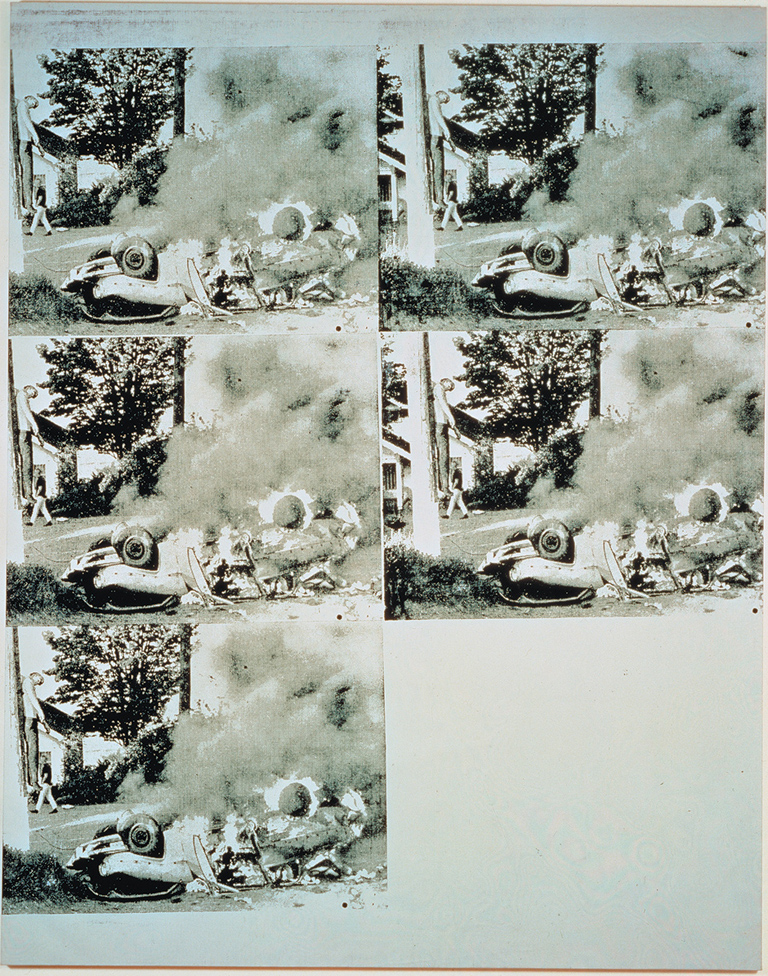

©2013 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol: White Burning Car III, 1963; silk-screen ink on synthetic polymer paint on linen, 100 x 78.75 inches. Reproduction, including downloading of Andy Warhol’s works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Art that plays with the idea of mechanical reproduction—the obvious example is the work of Andy Warhol—teaches us something of what it would be like to be a thing, an object. Warhol was also, not coincidentally, an enthusiastic proponent of corpse art, his Death in America series being strewn with dead bodies, all of which are presented with no whiff of human pity—although neither are they quite cold abstractions. On one level, the level at which they are most often celebrated, Warhol’s corpses make you feel nothing. And yet your awareness of your own emptiness is exactly what proves traumatic about them. “How can I be looking at this terrible thing and feeling nothing?” is the quintessential Warholian sensation and it’s had a very long afterlife. Uncomfortably numb: that’s still the non-emotion that so many young artists, across all media, are gunning for.

Thinking of Warhol and corpses it’s odd (to me) that I met—for the first time—the critic Hal Foster, on that September night, for it was a dinner at his apartment I was coming from. It’s almost twenty years ago now that he wrote of the Warhol effect in The Return of the Real:

The famous motto of the Warholian persona: “I want to be a machine.” Usually this statement is taken to confirm the blankness of artist and art alike, but it may point less to a blank subject than to a shocked one, who takes on the nature of what shocks him as a mimetic defense against this shock: I am a machine too, I make (or consume) serial product-images too, I give as good (or as bad) as I get…. If you can’t beat it, Warhol suggests, join it.

There Foster is defining something called “traumatic realism,” leaning on a Lacanian definition of trauma as “a missed encounter with the real.” We mechanically repeat the trauma to obscure and control the reality of the trauma, but in doing so reproduce, obliquely, some element of the trauma. The real pokes through anyway, in the process of repetition. One of his examples—Warhol’s White Burning Car III—has echoes of the Signorelli. Here is a corpse—thrown from a burning car and hanging upon a climbing spike in a utility pole—and here is a live man, strolling by, heading out of the frame. It’s an appropriation of a tabloid image, originally published in Newsweek.

On the one hand, as with the Signorelli, I am viewing the abject, unthinkable thing (myself as a corpse) and this, for me—and for Andy—is a way of dominating and controlling the trauma (of this idea). The silk screen screens the truth from me. But not entirely. A Warhol image, as Foster brilliantly argues, just keeps coming at you, partly hiding the real from you but also repeating and reproducing it unbearably. The repetition of the image—an unstable tower, three reps stacked beside two—proves key. Somewhere along the line, the sequence begins to morph. Thank God it wasn’t me starts becoming (perhaps in that final blank space) Oh Christ it will be me.*

This anxious double consciousness—it’s not me/it will be me—may be part of the price we pay for living with, and around, machines. Whenever we enter a moving vehicle, for example, or a plane, haven’t we always, already, in our minds, crashed and become corpses? Even before receiving our salty pretzels we see ourselves screaming and praying, falling through the sky, incinerated. And if we’re in that Warholian moment, everything else is false advertising. That’s another ongoing attraction of Warhol: whenever it’s strongly implied that we are going to live forever (almost every ad, TV show, and magazine—in-flight or otherwise—does this) we can think of Andy (who used the commercial language of these mediums) and know, deep in our naked selves, that it isn’t true.

Meanwhile the replication of nature at its most beautiful—beloved technique of Italian masterpieces—is the art best suited to sentimental humanism, allowing, as it does, the viewing subject to feel pity and empathy; to weep for all the beautiful people who have become or will become corpses (excluding me). Which is a response I would never entirely forsake, not for a half-dozen burning white cars. To look into the tender, unformed face of Titian’s Ranuccio Farnese—twelve-year-old scion of the ancient Italian clan—and see a boy whose destiny it was to become a corpse! And this despite his red doublet’s intricate embroidery, the adult sword hung about his narrow hips, the heavy weight of inheritance suggested by that cloak his father surely insisted he wear… All the signs of indelible individuality are here, yet none proved sufficient to halt the inevitable. (No amount of “selfies” will do it, either.)

Is my horror of corpses coeval with the discovery that I’m a time-bound “individual”? Before we were mere bodily envelopes, containing souls for a while, before these souls embarked on their journeys toward the infinite. In a culture that gives credence to eternal consciousness, corpses remain disgusting but aren’t, in themselves, “tragic.” The modern “trick” of portraiture—the arresting of a “single” moment in an individual life (made so much more poignant here, on the edge of adulthood)—may be an aesthetic illusion, but at least it helps remind us of what a large “event” a human life truly is, of how much is lost when corpsification occurs. We may be forever corpses—but once we were alive! It was the old masters that taught us the emotional power of individual representation. (And five hundred years later, space is still reserved in our newspapers for recent corpses—if they are one of “ours”—the dead furnished with stories as precise and elaborate as the Farnese embroidery.)

Of course, we learned our attitudes toward human suffering from them, too. Auden’s famous words fit Warhol’s burning car as snugly as they do Breughel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus or Piero’s Flagellation of Christ:

How well they understood

Its human position; how

it takes place

While someone else is eating

or opening a window or just

walking dully along.

But do all old masters do this equally well? The sheer technical skill, the perfected illusion, can sometimes be a block between (this) viewer and the useful emotion she is seeking. There are many beguiling Italian masterpieces. There are also moments when you have to remind yourself that the stable relationship they tend to configure, between me the subject and the painting-object (which I am contemplating as if it spoke of a truth that did not include me) is, in the final analysis, a gorgeous illusion.

The Signorelli, by contrast, stops you in your tracks. It has the gift of implication. It creates a triangular and unstable relationship—between you, the corpse, and the “someone else.” Looking at it, I am not a woman looking at a man carrying a corpse. I am that corpse. (Even if this is an idea I entertain for only a few seconds, preferring to be the “someone else.”) And I will be that corpse for infinitely longer than I have ever been an individual woman with feelings and ideas and arms and legs, who sometimes looks at paintings. It’s not me. But it will be me.

2.

Earlier, at Hal Foster’s, we’d talked of Karl Ove Knausgaard, the Norwegian author of a six-volume novel (or memoir?) called My Struggle (two volumes of which have been translated thus far). Everywhere I’ve gone this past year the talk, amongst bookish people, has been of this Norwegian. The first volume, A Death in the Family, minutely records the perfectly banal existence of “Karl Ove,” his unremarkable childhood, his troubles with girls, his adolescent attempts to buy beer for a New Year’s Eve party (almost one hundred pages of that), and the death of his father.

The second, A Man In Love, renders a marriage in as much detail as any human can bear:

What was going through her head?

Oh, I knew. She was all alone with Vanja during the day, from when I went to my office until I returned, she felt lonely, and she had been looking forward so much to these two weeks. Some quiet days with her little family gathered round her, that was what she had been looking forward to. I, for my part, never looked forward to anything except the moment the office door closed behind me and I was alone and able to write.

As a whole these volumes work not by synecdoche or metaphor, beauty or drama, or even storytelling. What’s notable is Karl Ove’s ability, rare these days, to be fully present in and mindful of his own existence. Every detail is put down without apparent vanity or decoration, as if the writing and the living are happening simultaneously. There shouldn’t be anything remarkable about any of it except for the fact that it immerses you totally. You live his life with him.

Talking about him over dinner—like groupies discussing their favorite band—I discovered that although most people felt as strongly about their time spent under Karl Ove’s skin as I had, we had a dissenter. An objection on the principle of boredom, which you sense Knausgaard himself would not deny. Like Warhol, he makes no attempt to be interesting. But it’s not the same kind of boredom Warhol celebrated, not that clean kind which, as Andy had it, makes “the meaning go away,” leaving you so much “better and emptier.” Knausgaard’s boredom is baroque. It has many elaborations: the boredom of children’s parties, of buying beers, of being married, writing, being oneself, dealing with one’s family. It’s a cathedral of boredom. And when you enter it, it looks a lot like the one you yourself are living in. (Especially true if, like Karl Ove, you happen to be a married writer. Such people are susceptible to the peculiar charms of Karl Ove.) It’s a book that recognizes the banal struggle of our daily lives and yet considers it nothing less than a tragedy that these lives, filled as they are not only with boredom but with fjords and cigarettes and works by Dürer, must all end in total annihilation.

But nothing happens! our dissenter cried. Still, a life filled with practically nothing, if you are fully present in and mindful of it, can be a beautiful struggle. In America we are perhaps more accustomed to art that enacts the boredom of life with a side order of that (by now) overfamiliar Warholian nihilism. I think of the similar-but-different maximalist narratives of the young writer Tao Lin, whose most recent novel, Taipei, is likewise committed to the blow-by-blow recreation of everyday existence. That book—though occasionally unbearable to me as I read it—had, by the time I’d finished it, a cumulative effect, similar to the Knausgaard.

Both exhaustively document a life: you don’t simply “identify” with the character, effectively you “become” them. A narrative claustrophobia is at work, with no distance permitted between reader and protagonist. And if living with Tao Lin’s Paul feels somewhat more relentless than living with Karl Ove, there is an element of geographical and historical luck in play: after all, Karl Ove has the built-in sublimity of fjords to console him, whereas Paul can claim only downtown Manhattan (with excursions to Brooklyn and, briefly, Taipei), the Internet, and a sackload of prescription drugs.

Lin’s work can be confounding, but isn’t it a bit perverse to be angry at artists who deliver back to us the local details of our local reality? What’s intolerable in Taipei is not the sentences (which are rather fine), it’s the life Paul makes us live with him as we read. Both Lin and Knausgaard eschew the solutions of minimalism and abstraction in interesting ways, opting instead for full immersion. Come with me, they seem to say, come into this life. If you can’t beat us, join us, here, in the real. It might not be pretty—but this is life.

Would the premature corpsification of others concern us more if we were mindful of what it is to be a living human? That question is, for the sentimental humanist, the point at which aesthetics sidles up to politics. (If you believe they meet at all. Many people don’t.) Concern over the premature corpsification of various types of beings—the poor, women, people of color, homosexuals, animals—although consecrated in the legal sphere, usually emerges in the imaginary realm. First we become mindful—then we begin to mind. Of our mindlessness, meanwhile, we hear a lot these days; it’s an accusation we constantly throw at each other and at ourselves. It’s claimed that Americans viewed twelve times as many Web pages about Miley Cyrus as about the gas attack in Syria. I read plenty about Miley Cyrus, on my iPhone, late at night. And you wake up and you hate yourself. My “struggle”! The overweening absurdity of Karl Ove’s title is a bad joke that keeps coming back to you as you try to construct a life worthy of an adult. How to be more present, more mindful? Of ourselves, of others? For others?

You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away, is the ability to just sit there…. That’s being a person…. Because underneath everything in your life there is that thing, that empty—forever empty.

That’s the comedian Louis C.K., practicing his comedy-cum-art-cum-philosophy, reminding us that we’ll all one day become corpses. His aim, in that skit, was to rid us of our smart phones, or at least get us to use the damn things a little less (“You never feel completely sad or completely happy, you just feel kinda satisfied with your products, and then you die”), and it went viral, and many people smiled sadly at it and thought how correct it was and how everybody (except them) should really maybe switch off their smart phones, and spend more time with live people offline because everybody (except them) was really going to die one day, and be dead forever, and shouldn’t a person live—truly live, a real life—while they’re alive?

This Issue

December 5, 2013

Adventures in a Silver Cloud

Can Obama Reverse the Republican Surge?

-

*

In a crypt in Rome the bones of some four thousand Capuchin monks, buried between 1500 and 1870, have been used to create mise-en-scènes: fully dressed skeletons praying in rooms made of bones, with bone chandeliers and bone chairs and ornamental walls covered in skulls. In the final room a memento mori is spelled out upon the floor: “What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you shall be.” ↩