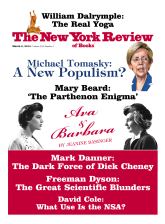

In 1949, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the studio that boasted “more stars than there are in the heavens,” released one of its typical productions. Based on a soap-opera-ish novel by Marcia Davenport, East Side, West Side put MGM’s assets on show: Cyd Charisse (in a non-dancing role), Nancy Davis (soon to be Mrs. Ronald Reagan), James Mason (at his most suave), and Gale Sondergaard and Van Heflin (both Oscar winners). The headliners were Barbara Stanwyck and Ava Gardner, appearing together for the first and only time. They portrayed the two women in Mason’s life, wife (Stanwyck) and lover (Gardner), and they were given a single scene to confront the situation. Stanwyck, the elder of the two, has the larger role of a wealthy Park Avenue woman: chic, well-mannered, cultured. Gardner gets the showier part as a trashy babe (a role Stanwyck might have played in her younger years).

Gardner, dressed in stark white with suitable cleavage, roams around the room like a restless tiger. She does most of the talking, warning Stanwyck that Mason will be available “only when I don’t want him…. I’ll call him and he’ll come running.” She tells Stanwyck to watch out because she knows men. Stanwyck stays calm. She doesn’t move a muscle, standing ramrod straight in a prim suit, matching hat and gloves, and double strand of pearls. When they are done deciding Mason’s fate (the female prerogative), Stanwyck sweeps confidently out the door, and then, alone and rattled, she starts to cry. This was Stanwyck’s famous trump card, her ability to make a rapid shift from tough to vulnerable. This was what you once got for your money from Hollywood: glorious junk enlivened by two fabulous and unique stars who knew what an audience wanted from them and who earned every cent they were paid.

Moviegoers had little trouble believing that Ava Gardner and Barbara Stanwyck might fight over a husband. Gardner’s next movie in 1949 was The Bribe, and it costarred her with Stanwyck’s real-life second husband, Robert Taylor. Very quickly, Gardner and Taylor, two of the most beautiful people in movies, were having a hot romance. “Our love affair lasted three, maybe four, months,” Gardner wrote in her autobiography, Ava: My Story, adding that it was “a magical little interlude.” (What Stanwyck thought about it went unrecorded.) East Side, West Side’s conflict between wife and lover mirrored the conflict between the same two women off-screen. Here lies a challenge for the movie-star biographer: Where does East Side, West Side end and real life begin? It’s difficult for anyone to know, sometimes including the stars themselves.

Gardner and Stanwyck are the subjects of two recent books: Ava Gardner: The Secret Conversations, by Peter Evans and Ava Gardner, and A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True, 1907–1940, by Victoria Wilson. Evans’s book is not a complete story of Gardner’s life and career, although it was originally meant to be. In 1988, Gardner, who had suffered a stroke and needed money while living in London, invited Evans to work with her as ghostwriter on her autobiography. (“I’m broke, honey. I either write the book or sell the jewels…And I’m kinda sentimental about the jewels.”) After consuming numerous bottles of white wine, the two sat down to work. About one third of the way into the project, Gardner abruptly fired Evans. He had failed to tell her that her ex-husband (and lifelong friend), Frank Sinatra, had once sued him for libel.

Gardner went on to write her book with new ghosts (Alan Burgess and Kenneth Turan). It was published in 1990, shortly after her death that same year. Evans (who himself died in 2012 before the publication of this second book) reconstructed these “conversations” out of his notes from their meetings, his research (such as it was), and his recordings of their late-night telephone calls (taped without Gardner’s knowledge). His book is shameless but highly entertaining. He’s selling everybody’s idea of who Ava Gardner was—boozy and bawdy and beautiful—with a book cover that shows her in black underwear and fishnet stockings.

Evans claims to be giving us the “real” Ava Gardner because of his “secret” conversations. As proof he wasn’t bought, he includes negative comments from people who knew Gardner. Dirk Bogarde warns, “She will eat you alive.” Writer Peter Viertel says, “You’ll have to fight her all the way.” Gardner herself gave him fair warning: “It’s my fucking life. I’ll remember it the way I want to remember it…. I’m not asking for a literary masterpiece.” However, the Evans portrait is still the Gardner image we know, a cross between her roles as the playful “Honey Bear” in 1953’s Mogambo and the earthy Maxine in Night of the Iguana (1964). She’s sassy, capricious, seductive, unpredictable, and funny. She recalls, for example, her life touring with Artie Shaw’s band before she became his fifth wife:

Advertisement

I was still as happy as Larry traveling with the band, hanging out with Artie and his literary pals. Guys like Sid Perelman, Bill Saroyan, John O’Hara. They were all bright, funny, interesting guys.

Artie said all I had to do was keep my mouth shut, sit at their feet, and absorb their wit and wisdom. I was happy to do that. I was comfortable with all those guys. But if I kicked off my shoes and curled my feet up on the couch, he’d go bananas. “You’re not in the fucking tobacco fields now,” he’d scream. He had a real phobia about me and tobacco fields.

In Evans’s book she’s her own version of Norma Desmond, more wacky than demented, but not at all confused about what Evans wants from her and why.

By contrast, Victoria Wilson (vice-president and senior editor at Knopf) tries to find the real person. In 1,044 pages, the first of two volumes, she takes Barbara Stanwyck’s life and career only as far as 1940. Wilson spent fifteen years doing in-depth research, interviewing people who knew and worked with Stanwyck, and watching every film she made. She wants to tell the complete story of Stanwyck in the historical setting of her times.

Instead of illuminating Stanwyck, the historical commentaries tend to distance her, even diminish her. She almost becomes a supporting player in her own story, sandwiched among details about the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 1934 failed campaign for governor of California by Upton Sinclair, Hollywood’s labor troubles, the rise of Hitler to power in Europe, etc., etc. In trying to lift Stanwyck out of a typical “star image” bio, Wilson nearly goes aground, but ultimately her book succeeds in several different respects: her fresh material on Stanwyck’s early years; a thorough understanding of the studio system; a deep appreciation for Stanwyck on film; and her awareness of Stanwyck’s independence, which allowed her to avoid typecasting.

In her first decade, by the time of Union Pacific in 1939, Stanwyck had played “midwestern farm women, New England factory girls, Park Avenue society women, business owners, prisoners, con artists, missionaries, mistresses, generals’ daughters, gamblers, wives, mothers, and sluts.” Wilson traces Stanwyck’s career, crediting the directorial skills of Frank Capra for first discovering her cinematic talent, as well as William Wellman, Cecil B. DeMille, John Ford, and Preston Sturges, whose script for 1940’s Remember the Night “released her” into comedy, which “lightens her” because she could “play the nuance.” Wilson describes movie plots in detail and eloquently defines Stanwyck’s acting strengths: “She was able to use her shoals of loss and regret, her feelings of being…the outsider…to create women on the screen whom audiences admired and knew to be true.” (Andre de Toth, who directed Stanwyck in 1947’s The Other Love, called her “the softest diamond in the world.”)

Ava Gardner and Barbara Stanwyck were separated by fifteen years in age, and arrived in Hollywood more than a decade apart. Although both were famous stars, neither ever won a competitive Academy Award. (Gardner was nominated once for Mogambo and Stanwyck four times, for Stella Dallas, Ball of Fire, Double Indemnity, and Sorry, Wrong Number. She received an honorary Oscar in 1982 for her “unique contribution to the art of screen acting.”) Both were at the top during the golden age of the Hollywood studio system, but one difference between them is fundamental: Ava Gardner was a product of the “star machine” and Barbara Stanwyck was not.

Gardner, from a not very well off but stable North Carolina family, arrived in town with a minimum of security and no acting experience, but was fed into a system that might be expected to take care of her if she behaved. Stanwyck, coming from a hardscrabble background in New York, arrived from Broadway with the security of a contract and solid experience, but took up her career independently and never let anyone own her.

Gardner’s security came with a price. Unable to pick and choose, she was assigned pedestrian films she had to carry (The Great Sinner in 1949, My Forbidden Past in 1951). She wasn’t given many opportunities to grow as an actress. The studio didn’t need that from her, and because of her spectacular looks, she presented something of a casting problem. Who would believe Ava Gardner as a nun, or a rocket scientist, or a neglected working girl in a tuna cannery? She was born to grab the spotlight, and having shaped her image as “a magnificent animal” (her billing for The Barefoot Contessa, 1954), Hollywood was content to present her that way.

Advertisement

Gardner became resentful and restless, and began to carouse, have affairs, and create problems. She didn’t care if she caused a scandal, particularly when she took up with the married Frank Sinatra and became the most famous “other woman” of her time. Ironically, it was easy for her studio to fuse this off-screen behavior to her on-screen persona, and the role of “Ava Gardner,” bad-girl-good-time-gal-sex-symbol, became an unbreakable image.

Stanwyck’s independence meant that she could negotiate her films and salaries, but she had to accept that she had no priority in any studio’s plans for casting. She lost significant roles as a result, such as the lead in Dark Victory (1939), which went to Bette Davis. Wilson points out that a studio “would have steadily built her up picture after picture,” as MGM did with Gardner, but Stanwyck didn’t want that: “She found it a constraint.” Stanwyck had to fight to get good films, but she had her own supporters, including her first husband, Frank Fay (an established born-in-a-trunk performer), a shrewd agent, Zeppo Marx (the fifth Marx brother), and particularly director Frank Capra, who saw what she was capable of and who guided her in four of her earliest films. As curator of the Frank Capra Archives, I spent many hours talking to Capra about his career, and Stanwyck was a subject he loved. A great admirer of her talent, discipline, and professionalism, he always stressed that since Stanwyck was never owned by a single studio for any length of time, no specific image was created for her. She had to create her own.

Both Stanwyck and Gardner knew Hollywood for what it was. Gardner kept the cheap coat she wore when she first arrived to remind herself where she came from. She preferred to hang out with nonprofessionals and lived as simply as she could. (“I’ll go on living according to my own standards,” she said.) Stanwyck, a disciplined professional who was friendly with her film crews, made similar statements: “It would be the same with me if I were a waitress in Peoria or a chambermaid in Oshkosh instead of a film actress in Hollywood.” Both women knew that fame was transient. “Movie stars write their books,” said Gardner, “then they are forgotten, and then they die.” Stanwyck warned Robert Taylor, when he first saw his name in lights, “The trick is to keep it up there.” She was coldly realistic about the world she lived in. “When you are up in Hollywood, you are accepted; when you are down, it is as though you do not exist.”

Ava Lavinia Gardner was born in North Carolina on Christmas Eve, 1922. Her father was a farmer who lost his property, and after cooking and cleaning in a girl’s dormitory, her mother opened a boardinghouse. Contrary to popular belief, Gardner was neither desperately poor nor uneducated. (“I’m tired of reading about how Ava grew up in poverty working in the fields,” said her sister, Inez. “We were poor, it’s true, but…actually we had a fairly good life.”) After graduating from high school, Gardner attended the Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, North Carolina, where she studied to be a secretary.

Her life changed forever when, in the summer of 1941, she went to New York to visit her older sister Beatrice (“Bappie”), who had married a photographer. When he placed a photo of the young Ava in his display window, it was spotted by a clerk in MGM’s legal department who called it to the attention of his superiors. Within no time, Gardner made a screen test that was by all accounts terrible. One of the Hollywood studio bosses who saw it was said to have exclaimed, “She can’t act! She didn’t talk! She’s sensational!” George Sidney, in charge of new talent at MGM, said, “Ship her out here. She’s a good piece of merchandise.”

On August 23, 1941, with a $50 per week standard contract, Gardner arrived in Hollywood on the Super Chief accompanied by Bappie as chaperone. She was eighteen years old, had one pair of shoes, carried a cardboard suitcase, and spoke in an unintelligible southern drawl. MGM fed her immediately into their star-making system. She was given lessons in how to walk, talk, sit, and stand. Her hair was done and redone. She posed in countless cheesecake photos, wearing bathing suits, filmy nightgowns, pirate outfits, tutus and tights, and Santa Claus hats.

She worked up the ladder from extra to bit parts to supporting roles, and within less than six years, she had married and divorced twice (actor Mickey Rooney and bandleader Artie Shaw), dropped her southern accent, and learned to use her natural sexual magnetism for the asset it was. In 1946, wearing a tight black dress with one strap over her shoulder, she sat at a piano and crooned “The More I Know of Love” to Burt Lancaster in The Killers. Suddenly, she was a star. Although Gardner adopted an “I don’t care” attitude toward her success, those who observed her during those years saw it differently. One said, “Her indifference was a pose. Her drive was extraordinary and ruthless.”

Barbara Stanwyck was born Ruby Stevens on July 16, 1907, in Brooklyn, New York. As a child, Stanwyck was farmed out to friends and relatives, her mother having died when she was four. (A drunk had caused her mother, pregnant with her sixth child, to fall from a trolley. A few months after her death, the father deserted his family.) Stanwyck dropped out of school at the age of fourteen. Unlike Gardner, she really was poor and uneducated. Needing to work, she followed her older sister Millie into show business, and began dancing in chorus lines at a young age. By the time she was sixteen, she was touring in the Ziegfeld Follies.

Her life changed when she was cast in a dramatic role in a Broadway play, The Noose, in 1926. She brought the house down as a desperate girl pleading with the governor to spare the life of the man she loves. With her name changed to “Barbara Stanwyck,” she opened spectacularly on Broadway in Burlesque in 1927, and by 1929 she was offered a contract to come to Hollywood to make a movie called The Locked Door. In 1928 she had married Fay, famous for his wit, his charm, and his alcoholism.

Mr. and Mrs. Fay arrived in Hollywood together in 1929, also on the Super Chief, but under different circumstances from Gardner’s. The Fays were already successful, posing on the back of the train with Irving Berlin and movie mogul Joe Schenck. Stanwyck, leaning on her husband, carried a fur coat, was stylishly dressed, and had a contract to star in a Warner Brothers sound motion picture for $1,500 per week. From the first day of her decades-long career in movies and television, Stanwyck was recognized as a leading actress. No cheesecake photos or experimental hairdos.

Wilson wants to define who Stanwyck was on screen across four decades in a myriad of roles, and also seek out the facts of her reclusive private life. Evans presents a one-dimensional Gardner, but Wilson, an unabashed admirer of Stanwyck, describes, but doesn’t analyze, some apparent contradictions in Stanwyck’s life. Stanwyck is the orphan who so badly wants a family that she lets Frank Fay bully her adopted son, Dion. She herself ultimately banishes the boy to military school, instructing him to refer to her as “my mother, Barbara Stanwyck.” She’s down-to-earth and democratic on the set, but yells at her brother, Byron, who wants to wed a woman she doesn’t like, “You’re going to marry some dumb little extra?” Most inexplicably, she remained doggedly loyal to Fay, whose drunken binges and abusive treatment of her were well known, until she finally sought a divorce for “grievous mental suffering” at the end of 1935.

Do we really care who someone slept with in 1940? What matters about Ava Gardner and Barbara Stanwyck is to be found on the screen, not in their diaries. They were early career women, ending up alone and self-supporting. They are “alive” today because their onscreen images represent a peculiar type of female power.

Gardner’s manufactured image was so much a part of the culture that she didn’t even have to appear onscreen to be palpably present. In The Barefoot Contessa, she “enters” with a click of castanets, a swaying beaded curtain, and a moving spotlight, but she’s not seen. Her dance around the nightclub floor is depicted only by its impact on the close-up faces of the male spectators.

Stanwyck became one of the greatest interpreters of female vulnerability the movies ever had. In Clash by Night (1952), she plays a former good-time girl trying to do right by her stolid husband, but she’s tempted by a sexy and knowing Robert Ryan. Alone in her kitchen, feeling the heat, she tries to pour herself a cup of coffee. Her hand starts to shake, the cup starts to rattle, and she just can’t do it. Finally, she gives up and breaks down weeping, the hardbitten woman showing the audience who she is, and doing it with nothing but a coffee pot.

Both actors could be dangerous on film. Gardner destroys men through sex and by being beautiful enough to drive them mad, but Stanwyck lifted male destruction to an art form. In Double Indemnity (1944), with nothing but an ankle bracelet and a blond wig, she lures Fred MacMurray to murder her husband. She’s both comic and cruel in The Lady Eve (1941) as she reveals past amours on her wedding night to the hapless Henry Fonda, and horrifically cruel in The File on Thelma Jordon (1950) when she jabs a cigarette lighter in Richard Rober’s eyeball. Late in life, when most stars had long since retired, she played a steely matriarch in The Thorn Birds (1983) on TV, and was unafraid to enact an older woman’s sexual desire.

I met both Ava Gardner and Barbara Stanwyck in the 1980s. Both were tough and wary, but vulnerable in different ways. Gardner was past her prime, a bit puffy around the eyes. She walked toward me with feline grace, and despite everything, she was nothing short of spectacular. Stanwyck showed no sign of age whatever, other than her white hair that she had been refusing to dye for decades. She had the body of a teenager and she was swathed in a sequined bright red sheath. Both women wanted to make it clear that “I’m still here.”

Gardner and Stanwyck died within five days of each other in January of 1990, Stanwyck at age eighty-two and Gardner at sixty-seven. Evans furthers the legend of Ava Gardner as the woman who liked sex and booze and did it her way. (To paraphrase John Ford, when the image becomes legend, print the legend.) Wilson, in the first of her two volumes, tries to see Stanwyck objectively, tracing all the facts about her she could find. But no one will ever know who they really were. They were too good at playing roles, both on and off the screen.

This Issue

March 6, 2014

In the Darkness of Dick Cheney

A New Populism?