The following was written on the fiftieth anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s film “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”

Stanley Kubrick began taking pictures for Look magazine in high school. He became a full-time staff photographer while in his teens, and you can find some of his extraordinary work of the late 1940s online: black-and-white shots of New Yorkers at their occupations of craft or commerce—dancers at a mirror before a nightclub show; a boxer refitting his mouthpiece between rounds; a small girl staring up at a roller coaster—“the scrimmage of appetite” in the most far-flung postures of idleness or wonder.

Kubrick said in an interview that setting up his darkroom was good practice; he thought the right preparation for any line of work was to organize a whole project and see it through yourself. Financing, writing, and filming his earliest movies on a shoestring, he turned himself into a director whom the big studios would back to do what he wanted to do. He was venerated for that independence. But he became the most admired American director of his generation for other reasons, too: the continuously grown-up subject matter—in a Kubrick film, there is never a family dog—and the always-disquieting use of space in relation to the human figure. The man behind the camera was possessed of an uncanny power of detachment; and this gave all his films a style, formal, rigorous, and unfamiliar, that no other director can ever be confused with.

Dr. Strangelove was released on January 29, 1964. It was Kubrick’s seventh film, but only the fourth in which he took much pride. Before it had come The Killing (1956), a crime story about a robbery during a horse race; Paths of Glory (1957), a film of World War I centering on a court-martial after a defeat in battle; and Lolita (1962), which Kubrick transformed into an unsettling romantic drama. Spartacus (1960) was more famous than any of these predecessors, but Kubrick would later disclaim interest in every aspect of the finished film except the sequence of gladiatorial training. There are, incidentally, in many of his films, elaborate scenes of training, or the planning of a large-scale action (often a violent, illegal, or impersonal action). Such rehearsals for action are at the heart of the war-room sequences in Dr. Strangelove. You see them again in the recorded regimen of marine training that takes up the first half of his film about the Vietnam War, Full Metal Jacket (1987).

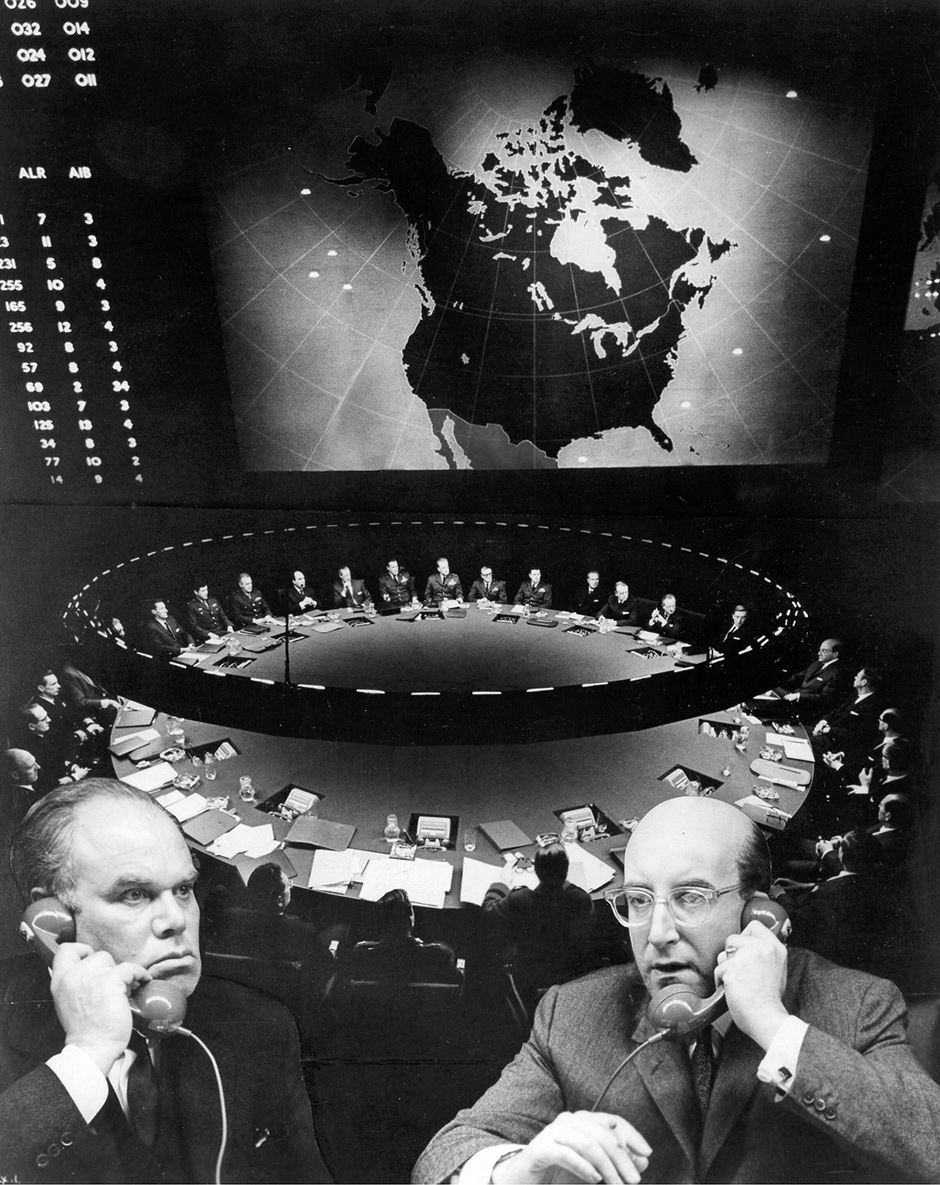

What was the war room? This astonishing cavern, whose dimensions were 100 feet by 130 feet (with a ceiling 35 feet high), was built for Dr. Strangelove by the set designer Ken Adam. Nobody had ever seen anything like it. And yet everyone who thought about such things, in the early 1960s, must have imagined such a place inside or underneath the Pentagon. There has never been a darker room than this. You come to know the war room as an immaculate profane sanctum, with its polished black Formica floor, its enormous circular table, and the suspended halo of fluorescent light above. The president, his advisers, the Russian ambassador, and an impressive array of generals all sit around the table as if it were their natural habitat. In little stacks in front of the generals are strategic studies with titles you can read if you try. One of them is called World Targets in Megadeaths.

Dr. Strangelove was filmed at Shepperton Studios, in a London suburb close to Heathrow Airport. Its germ lay in the Cuban missile crisis and the argument, during the 1960 presidential campaign, about the impending danger of a “missile gap”: the supposed advantage the Soviet Union would soon enjoy in the manufacture and deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles. John F. Kennedy ran to the right of Richard Nixon on that issue in 1960. The missile gap turned out to be a sham, as Kubrick and many others suspected (though nobody in 1963 could know how large the error was): the Russians had never been within hailing distance of the United States in the production and deployment of missiles. The gap, nonetheless, was a suitable rhetorical device to stoke the fears and passions of the cold war.

President Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had approved of contingency plans by the US military for an all-out nuclear attack. As Eric Schlosser points out in his recent book Command and Control,1 Eisenhower disliked and feared but declined to obstruct the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), which laid out the conditions for massive retaliation by the military acting in the absence of civilian leadership. Such an attack once triggered could never be recalled. This was the basis of “Wing Attack Plan R”—the command issued in Dr. Strangelove in a psychotic surge by General Jack D. Ripper.

Advertisement

Eisenhower’s words on this subject were better and wiser than his actions. He said what he knew when it was almost too late to matter, in his farewell address on January 17, 1961:

This conjunction [which had produced SIOP] of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government…. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

The idea that it was necessary to curb the “military-industrial complex”—a phrase coined in Eisenhower’s farewell speech, exactly three years before the release of Dr. Strangelove—had a minimal impact on the early policy of the Kennedy administration.

All of Kubrick’s intelligence went into the assembly of his cast and crew; but the film had to dodge more than its share of accidents in production. Peter Sellers had agreed to play four parts, including the Texan pilot of the solitary B-52 that eludes Russian radar and air defenses; but Sellers got into a row with Kubrick on the set of the fuselage (suspended from the studio ceiling fifteen feet above the ground), which ended with him falling and breaking his leg. The studio’s insurers now forbade him to play a part that required athletic movement under stress. Kubrick, on the spot, decided that Sellers’s replacement in that role couldn’t be a star; it had to be a plain person to match the impersonations by Sellers of the other three roles he was inhabiting: the Nazi émigré scientist, the American president, and the British liaison officer at the air force base.

To fill the gap, he brought in Slim Pickens—a rodeo cowboy who had played the deputy in Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks. As it turned out, Pickens carried to perfection the role of the B-52 pilot Major Kong; never more so than in the blessing he delivers to the crew of his plane on the verge of “nucular combat, toe-to-toe with the Rooskies.” Speaking with instinctive fatherly grace and choked with empathy, “I got a fair idea,” says Major Kong, “the kinda personal emotions that some of you fellas may be thinkin’. Heck, I reckon you wouldn’t even be human bein’s if you didn’t have some pretty strong personal feelin’s about nucular combat.”

Dr. Strangelove was originally planned as a melodrama, like Fail Safe (1964), another movie about nuclear catastrophe produced about the same time. But Kubrick changed his mind in mid-course. In a memoir of the film, Terry Southern spoke of the phone call he had received one day from Kubrick, who suggested that they join forces in rewriting the story:

He told me he was going to make a film about “our failure to understand the dangers of nuclear war.” He said that he had thought of the story as a “straightforward melodrama” until this morning, when he “woke up and realized that nuclear war was too outrageous, too fantastic to be treated in any conventional manner.” He said he could only see it now as “some kind of hideous joke.”

A talented movie director needn’t have a vision of life, but a major artist in filmmaking often does; and like Krzysztof Kieslowski, whom he greatly admired, Kubrick was one of those who do have such a vision. Human beings for Kubrick possess something of the quality of mobile dolls or manikins. Their actions are governed by determinations beyond their grasp. Their own approval of their actions is so self-deceived that the only thing an artist can do is photograph them and allow plenty of scope for the pictures to show what is happening.

Kubrick was a master chess player; and to a large extent, he thought of his characters as chess pieces (but pieces that believe they are making the moves of their own volition). That severe assumption led, in some of his work, to a prejudice against the subtle registration of feeling that goes to make good realistic acting. You can see the effect of the prejudice (and the exclusion of spontaneity it enforced) in some of his later films, especially 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Barry Lyndon (1975), and Full Metal Jacket. There are traces of the prejudice, too, in the sober stretches of flat dialogue in Dr. Strangelove, inside the B-52 and in the war room.

Yet Kubrick loved adventurous acting when it drove all the way over the edge of cartooning. He was a helpless believer in the improvisations of Sellers as Clare Quilty in Lolita, which go on beyond any excuse of economy, and of Jack Nicholson in the second half of The Shining (1980). He gave free rein to Sellers again in two of his three roles in Dr. Strangelove: as the ex-Nazi physicist Strangelove, who in moments of passion calls the president “Mein Führer,” and as the president, Merkin Muffley (who looks a good deal like Adlai Stevenson—the symbol, for conservatives, of everything intellectual and unmanly about American liberalism). These performances by Peter Sellers are incomparable. They are excessive, and they inspire gratitude.

Advertisement

Kubrick had the wit to cast as a foil to Sellers, in the role of General Buck Turgidson, a talent of utterly opposite temper. He had seen George C. Scott as Shylock in a New York production of The Merchant of Venice; and Scott makes at once a credible portrait and a convincing caricature as the general. Buck Turgidson is said to have been modeled on Curtis LeMay, the commander in charge of the American bombing of Tokyo in World War II, who later became the charismatic head of the Strategic Air Command and chief of staff of the air force in October 1962. LeMay, along with the other Joint Chiefs, at the height of the missile crisis had urged President Kennedy to bomb the Russian emplacements in Cuba. The potentially disastrous advice came closer to being followed than anyone could have guessed at the time. For, as we now know from Robert Caro’s The Passage of Power,2 Vice President Johnson sided with the generals.

The memorable scenes in the movie are beyond counting, but let us count to two or three. Begin with the monologue by General Ripper on the dangers of fluoridation—“the most monstrously conceived and dangerous Communist plot we have ever had to face”—the effects of which he first became aware “during the physical act of love.” Listen, closely, to the therapeutic tones of the phone call by the American president to the Soviet premier, in apology for the fact that one of his generals “went a little funny in the head.” Note the strangely probable quality—something that could be said by such a person in such a place—of the monologue by Strangelove on the idea of a super-race, preserved underground from the nuclear attack and renewing itself for generations: a race that might incorporate select specimens of the military command and the policy elite.

All of these moments were the offspring of Kubrick and Terry Southern working together even as the movie was shot, inventing and rewriting from day to day. Other choices came from Kubrick the photographer, working alongside his cinematographer Gilbert Taylor (who would go on to supervise the camera work on A Hard Day’s Night). The wide and medium shots of the war room hold that hollow space forever present in our mind’s eye. The low-angle close-ups of Sterling Hayden as General Ripper show the monstrous reality of the man as if superimposed on his heroic self-image. And then—an odd point and easy to miss—there is the decision to render with a hand-held camera the scenes of conventional combat between the American troops inside and outside Ripper’s air-base fortress. We are made to feel the roughness of the older way of battle, the jolt and charge that the generals love; yet we are held back from nostalgia by the jarring reminders of a nerve-shattering violence, even in a battle confined to machine guns.

Dr. Srangelove is one of the masterpieces of filmmaking. And it is very much an American masterpiece—even though it was made by an expatriate artist in England who would never direct another film in this country. It may seem short at ninety-five minutes, for the treatment of so grave a subject, but it does not feel too short or too long by a single inch. Its episodes in three settings—the air force base, the war room, and the B-52—come to us in punctual succession, but individually, they have the slowness at times of a process of bureaucratic deliberation. The deep preoccupation of Dr. Strangelove is not, in fact, war, but rather the political development of which modern war has been only the largest symptom: the bureaucratization of terror.

What remains peculiar about the film, considered as a comedy, is that it prompts a kind of laughter that leads back to thought. For a while, it may carry the high spirits of a cabaret skit, where we know all along that the lights will be turned up afterward. But in back of every reversal of the plot sits the dark scientist of war, the strategist in his wheelchair, Dr. Strangelove. Death to us is life to him—“the angel of death,” as he is called by a flicker of implication once in the film. His hand will be at the switch even after the lights go up.