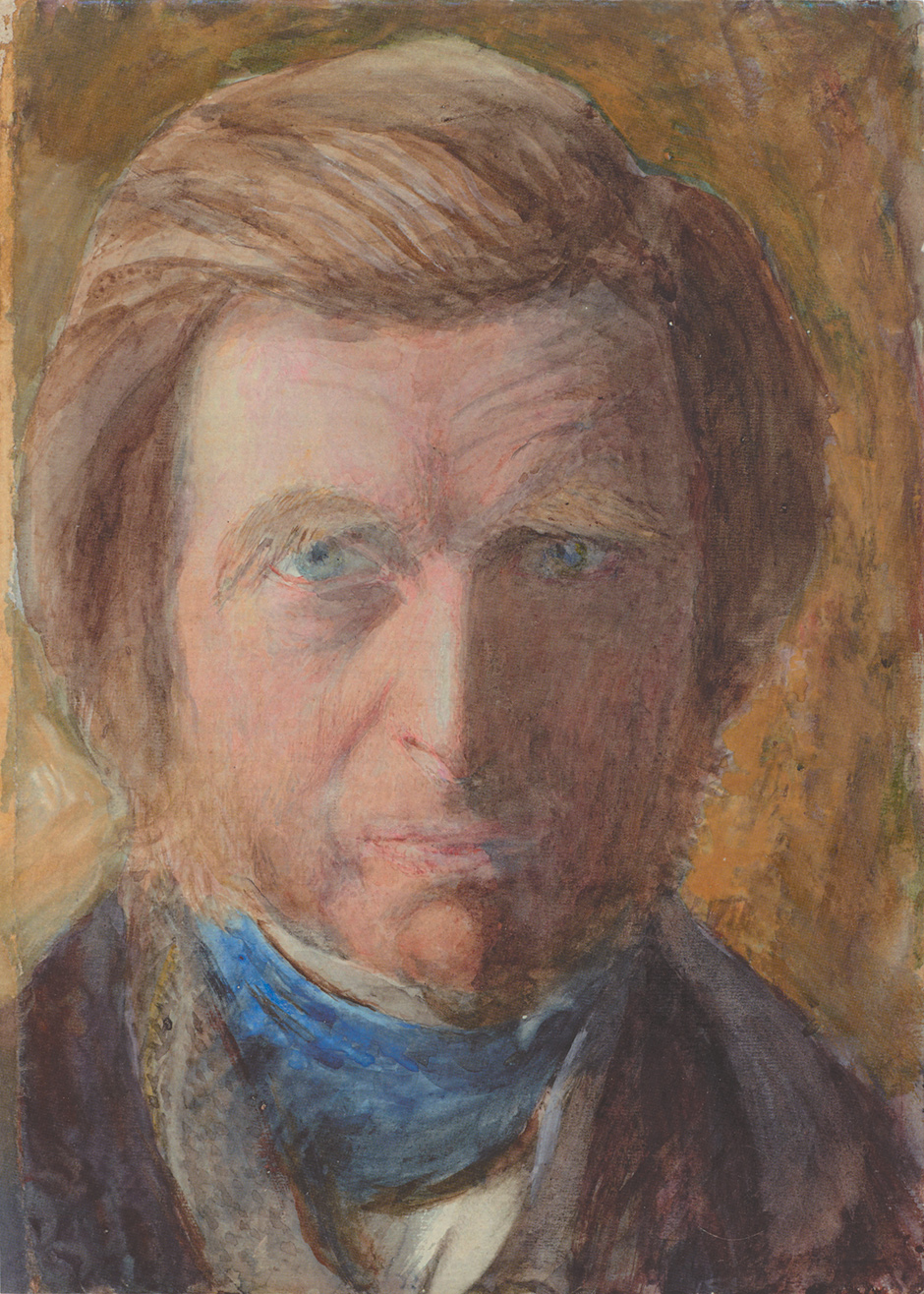

Though John Ruskin is generally thought of as a great prose stylist, social reformer, and art critic, few consider him a great painter. But Conal Shields does.

In the catalog to a stunning exhibition now in Ottawa and headed for Edinburgh—“John Ruskin: Artist and Observer”—Shields places him “among the greatest of English painters and draftsmen,” and wonders at “the relative neglect of his achievement.” Going through the 140 artworks collected here—some from private collections, and some never before exhibited in public—one is tempted to agree with him. The precision and detail of Ruskin’s prose descriptions are given sharp vindication in the pen, graphite, and chalk drawings—and especially in the brilliant watercolors. Ruskin was a fascinated student of geology, crystallography, botany, dendrology, ornithology, and meteorology, and his drawings in all these fields express his love (the only proper word) for each item his brush fondles onto the paper.

One of his most-used books, over the years, has been The Elements of Drawing, in which he mainly teaches his students how to see. Most people, he says, see what they expect—for instance, this is a tree—and look no deeper. They never actually realize what a complex, living thing any particular tree is. His drawings give a virtual biography of every tree he draws:

How troublesome trees have come in its way, and pushed it aside, and tried to strangle or starve it; where and when kind trees have sheltered it, and grown up lovingly together with it, bending as it bent; what winds torment it most; what boughs of it behave best, and bear most fruit; and so on.

So, in the exhibition, Ruskin gives us the tremendous drama of a whole tree, in graphite, pen, and pencil, with wash and white bodycolor; but also, with finest lines of pen and ink, he records the particularities in a foot or so of lightning-gashed trunk, with sprays of leaves growing from its wounds.

One of the main things he wanted people to see, in his Elements of Drawing, was color. Again, most look at a thing and think it is just red, or green, or whatever. He said there is no such thing in nature as a solid color, but colors are “continually passing one into the other.” Thus, in this show’s wondrous watercolor Study of a Velvet Crab, one cannot name as one color any particular spot on the crab, or say how it is constantly changing into equally unnamable tints. Though the catalog gives generally good images from the show, its reproduction cannot approach the delicacy and subtlety of this painting. Conal Shields, in one of the four scholarly essays in the catalog, writes of the crab:

The brush dances over some sections of the image and elsewhere drags its heavy loaded paint mixes into the nooks and crannies of the carapace. Luminosity and light resisting sculptural solidity tease the eye. It is iridescent with refracted and reflected light. A compound of gorgeous hues and intricately detailed but never costive draftsmanship, prompting the spectator to slip and slide over certain parts, to linger upon others, and to chase down detail that comes close to vanishing on the closest inspection, this is genuine visual wit.

At other places in his treatment of color in the Elements, Ruskin says that the only way to suggest the richness of some colors is “breaking one colour in small points through or over another.” In a sparkling picture of a bird (a kingfisher), we accordingly see a muted purple of the wing sown with dashes of a brilliant blue. Ruskin said that he painted what he could not put in words, even with the extraordinary range of words he commanded. He also meditated on, and grieved for, the impermanence of all things, even the rocks that built up mountains. He saw that even the Matterhorn was the product of and in the process of change, created by heat and upheaval and compression. He could write the biography of a boulder as well as a tree, since everything is in flux.

When a student said that he was describing natural processes, what Virgil called “the living rock,” not a made thing like a brick, Ruskin painted a broken piece of brick, with all the scars of its passage through time—its mutilations after its manufacture, its many-striated discolorations, and green moss growing on it. With the help of brilliant foreshortening and bodycolor for the moss, he gives the object a 3-D immediacy, as if it had dropped glowing out of the sky, not baked mud but a meteorite.

The range of these paintings made one journal’s art editor ask, at the press tour before the show opened, how Ruskin’s stature as an artist can have been so neglected. Shields, as we saw, makes the same remark in the catalog. The reason for the lack of attention to this side of him is simple: he did not paint to get any attention but his own. His father, who tried to shepherd his career, complained that he was doing things with no expectation of recompense or recognition. Ruskin ruefully remembered, in his memoir Praeterita, how his father

Advertisement

entirely, and with acute sense of loss to himself, doubted and deplored my now constant habit of making little patches and scratches of the sections and fractions of things in a notebook which used to live in my waistcoat pocket, instead of the former Proutesque or Robertsian outline of grand buildings and sublime scenes. And I was the more viciously stubborn in taking my own way, just because everybody was with him in these opinions.

Ruskin spent hours on most days making elaborate or simple records of things—a particular tint of dawn light, the state of a flower’s opening bud, a detail from a building or a painting—to keep a memory of what he saw, renewable when he lectured or taught or wrote. He was especially anxious to record details threatened by the nineteenth century’s crude ways of “restoring” artworks. But even aside from practical purposes, he did not feel he had truly seen a thing until he tried to copy just the right contours of it, its colors in and out of shade, its “individuating.” This made him see that what he had admired when looking superficially was “about five times as beautiful as I used to do, and as I can’t draw much better, I am reduced to knocking my fists together and moaning.”

We might ask, today, why he could not have kept his visual records with a camera. And he asked himself that. He was an early and enthusiastic user of the daguerreotype. Christopher Newall, a principal curator of the show and editor of the catalog, told me that this is the first Ruskin exhibition to show his uses of the camera, placing his original daguerreotypes next to drawings of the same scenes. Ruskin bought the photos, or took them himself, or trained his servants to take and develop them. He used them as a supplement rather than a substitute for making his own images.

He liked photos of a building’s whole façade, to “place” his own study of a detail. In the case of one church façade (San Michele in Lucca), the daguerreotype gave a fine record of the structure, but the camera could not read the confusion of stains and shadow in the reliefs running above the topmost arcade. And that is precisely what Ruskin picked out more clearly (indeed, more delicately than the catalog print can show) in his own watercolor. Ruskin was constantly verifying, correcting, or supplementing his work of eye and hand, words and paintbrush and camera.

To follow him in this daily quest does exactly what his Elements of Drawing was meant to do—make us see. We have a record of one man’s continual effort to perfect his seeing ability. We get samples of his records of dawns, all so similar and so very different. Ruskin studies not only cloud configurations, light playing through clouds, but the effect of that light on things below. He knew that Homer’s “rosy fingered dawn” was not radiating separate “fingers” as in the old Japanese flag, but was touching parts of the land and sea with its rosy glow—the daytime equivalent of Shakespeare’s moon “that tips with silver all these fruit-tree tops.”

So one reason for his neglect as an artist is that he rarely completed pictures of a conventional sort. Christopher Newall put only three of Ruskin’s works in his fine book, Victorian Watercolours,1 and we see why. Though Victorian watercolorists were highly skilled, their works were generally of vignettes, sentimental or preachy. (The exception was Ruskin’s own idol, Turner.) They were doing just the thing his father wanted John to do. The elder Ruskin wrote to a friend about his son’s squandered energies:

He is drawing perpetually, but no drawing such as in former days you or I might compliment in the usual way by saying it deserved a frame; but fragments of everything from a Cupola to a Cart-wheel, but in such bits that it is to the common eye a mass of Hieroglyphics—all true—truth itself, but Truth in mosaic.

There is an important parallel for this father–son clash that is missing in the show and its catalog. The elder Ruskin, himself a prosperous businessman, mourned his son’s fierce attacks on the laissez-faire economics of the Manchester School. This reaction shook the almost dictatorial authority Ruskin had established over art history in the middle of the nineteenth century. Many other people joined his father in telling John that he should stick to what he knew and not meddle in other parts of life. But Ruskin saw his social criticism, especially in the scorching prose of Unto This Last, as a natural part of his art criticism. He had always been interested in workmanship. How could he not be concerned about workmen? His concern for them made him campaign for their better working conditions, wages, housing, insurance, and education. He set up his own school for them, established a workmen’s Guild of Saint George, and gave away much of the wealth he inherited from his father to causes that consumed, gradually, as much of his time and energies as the study of art.

Advertisement

This important side of Ruskin is ignored in the exhibition. Is that because he did not put this concern in his drawings? Perhaps. But it would be odd if there were no connection between such vital aspects of his life. In fact, the justification offered by the National Portrait Gallery of Scotland for hosting this show is that it is a kind of autobiographical portrait of the man. That should send up caution signals. Biographies of Ruskin have done their own part in deflecting attention from Ruskin the social prophet—hailed as such by Tolstoy, Gandhi, and others—to Ruskin the sexually wounded bipolar man who succumbed to lunacy in his final years. Ruskin, on the night of his wedding to Euphemia Gray, could not consummate the marriage, then or ever, because something about Effie’s naked body repelled him. Instead, he had an intense spiritual yearning for a girl, Rose La Touche, who died young and visited him in visions (like Dante’s Beatrice). This is the sexually crippled Ruskin who figures now in plays, novels, movies—and even in an opera.2

And unfortunately this is the Ruskin featured in this show’s catalog. His sexual repression is expressed, we are told, in compensatory fixations on mountain clefts and caverns as vaginas. Well, sure enough, there are some split rocks here—how could Ruskin have drawn hundreds of mountain scenes and avoided them? Volume IV of Modern Painters is entirely devoted to mountains, for which he made fifty detailed drawings just of Chamounix in a matter of weeks.3 But given his own inhibitions, in line with Victorian morals and clothing, how would he even know what a vagina looks like, to keep recognizing it in the mountains he studied? It used to be said that his wife’s pubic hair was an unwelcome revelation on his wedding night, since none of the paintings he knew showed it—which is false. A more likely conjecture is that Effie was menstruating. He may have glimpsed, briefly, her mons veneris, pubic hair, and perhaps vulva, but that does not mean we should find them, as is claimed by the catalog, in his rocky image Moss and Wild Strawberry, painted a quarter of a century after that fleeting glimpse.

It is true that Ruskin’s heated religious upbringing made him inhibited and guilty about sex. It is also true that he had the Victorian desire to see women as angels, and to focus on little girls as more angelic than others—a trait shared by American Victorians like Henry Adams and Mark Twain. This form of nympholepsy did not make these men pedophiles. Rose was Ruskin’s Beatrice or Laura, not his preyed-upon Lolita.

Since the sexual aspect of Ruskin’s guilt gets attention in the show, one should consider the greater guilt that lay behind Ruskin’s social conscience. John Rosenberg and other critics recognize that Ruskin was troubled by his life of privilege when he became acquainted with the poverty and exploitation of the lower classes in England and in Europe generally. This socially productive aspect of the religious upbringing of evangelicals has been studied by David Hempton in his Evangelical Disenchantment (2008). It is not surprising that evangelicals were so prominent in reform causes like abolitionism, suffrage, and guild socialism. Even Ruskin’s tremendous importance for the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts movements was motivated by his belief that they elicit the creative capacity of workmen. He wanted to justify his own life by work. As the Slade Professor at Oxford, he even took his class out to repair roads in a local suburb (his undergraduate navvies on this project included Oscar Wilde and Arnold Toynbee).

It has become all too easy to forget some of the greatest political writings of the modern world in a concentration on the “crazy Ruskin.” When the British Labour Party was formed in 1906, the book most cited as an influence on their thinking by the first twenty-nine MPs elected was Ruskin’s Unto This Last, not Marx’s Capital. Ruskin called Unto This Last “the one [book] that will stand (if anything stand) surest and longest of all work of mine.” Many of the programs that the Labour Party passed, or tried to pass, were inspired by him. Naturally, many reviewers at the time were horrified that he could defame the great Manchester School—one said that Ruskin must be crushed before “his wild words destroy us all.”4

It is surprising that this new exhibition can present itself as a visual autobiography of Ruskin, yet entirely neglect this aspect of him. There are many drawings of Gothic architecture in the show—yet no mention of his connection between Gothic and workmen. There are obsessive tracings of sky and clouds—yet his ecological concerns for a coal-darkened England are nowhere mentioned. There are frenzied scrawls in his later years, all connected with his mental illness as a private thing—yet he also suffered political anguish at the time.

Ruskin was more haunted by sweatshops and belching industrial smokestacks than by vulvas and vaginas. This exhibition needs a tonic dose of George Bernard Shaw, who wrote:

There are always a few cases in which exceptional men and women with sufficient unearned income to maintain themselves handsomely without a stroke of work are found working harder than most of those who have to do it for a living, and spending most of their money on attempts to better the world…. John Ruskin published accounts of how he had spent his comfortable income and what work he had done, to shew that he, at least, was an honest worker and a faithful administrator of the part of the national income that had fallen to his lot.

This was so little understood that people concluded that he must have gone out of his mind; and as he afterwards did, like Dean Swift, succumb to the melancholia and exasperation induced by the wickedness and stupidity of capitalistic civilization, they joyfully persuaded themselves that they had been quite right about him.5

The exhibition will be going to Scotland in the summer, which is appropriate. Ruskin’s forebears and upbringing were Scottish—he spoke some of the most beautiful English sentences ever written with a Scottish accent—and some of his fondest memories, pellucidly recalled in Praeterita, were of that country. The brilliant artist will rightly be celebrated when the show arrives there—and perhaps the political genius will be remembered as well, closer to home.

-

1

Phaidon, 1987. ↩

-

2

There was a silent film, The Love of John Ruskin (1912), a short film, The Passion of John Ruskin (1994), and I hear there is a feature being made. ↩

-

3

Nicholas Penny, Ruskin’s Drawings (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1988), p. 24. ↩

-

4

John Rosenberg, The Darkening Glass (Columbia University Press, 1961), pp. 109–131. ↩

-

5

The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (Brentano’s, 1928), pp. 61–62. ↩