Charlie Smith’s Jump Soul comprises excerpts from seven previous volumes ranging from 1987 to 2009 (Red Roads, Indistinguishable from the Darkness, The Palms, Before and After, Heroin and Other Poems, Women of America, Word Comix) and a remarkable new collection, forty-six poems entitled Godzilla Street, his strongest work yet.

His poetry is in some ways typically modern and American: awash in idiomatic cross talk and leaps in register, given to all-encompassing lists. It can sometimes seem as if Smith is “on a long run/of quirky asides,” but the poetry grows distinctive for how it records the “give-and-take of the fracas,” the conflicting demands of inhabiting the shared life, particularly life in the city. He has a strong understanding of how to compress and evince, a great ear, and a terrific sense of where the desolate and the absurd overlap.

His tone is by turns amused, bitter, angry, both self-pitying and tough-talking. Like all hard-bitten romantics, he’s given to epiphanies, even if a learned sense of irony often makes him hold them at arm’s length. In “The Paris of Stories,” he describes an “apparent elaboration—the sunset, we mean,” as “brilliant, fucking sublime, the desperation turning to quality yellow/on our faces, the way//earth time includes these confusing generous passages,/gets to us.” Like Frost, Smith has a lover’s quarrel with the world. Even as he’s experiencing something beautiful, he’s questioning it (“apparent,” “confusing”) and finding language inadequate to the moment (“fucking sublime”).

The search for consolation and transcendence in Smith is always a little manic and frazzled and suspicious. If he’s a love poet, it’s love that ends in divorce and recrimination; his speakers are self-accusing, jaggy, recalcitrant. (There’s also an occasional not-so- subtle self-aggrandizing: “I was supposed to fly down to see my brother,/but I got sidetracked by some girls/and was two days late.” Some?) He’s a novelist as well as a poet, but the poems don’t feel like a novelist’s poems. Their primary concern is not with narrative but with detailing an instant of consciousness. Often they start with ellipsis, as if the reader had turned the dial of his attention and tuned in to a voice already mid-sentence. The work’s directness is persuasive and Smith offers up truths as they occur to him, no matter how distasteful or pessimistic.

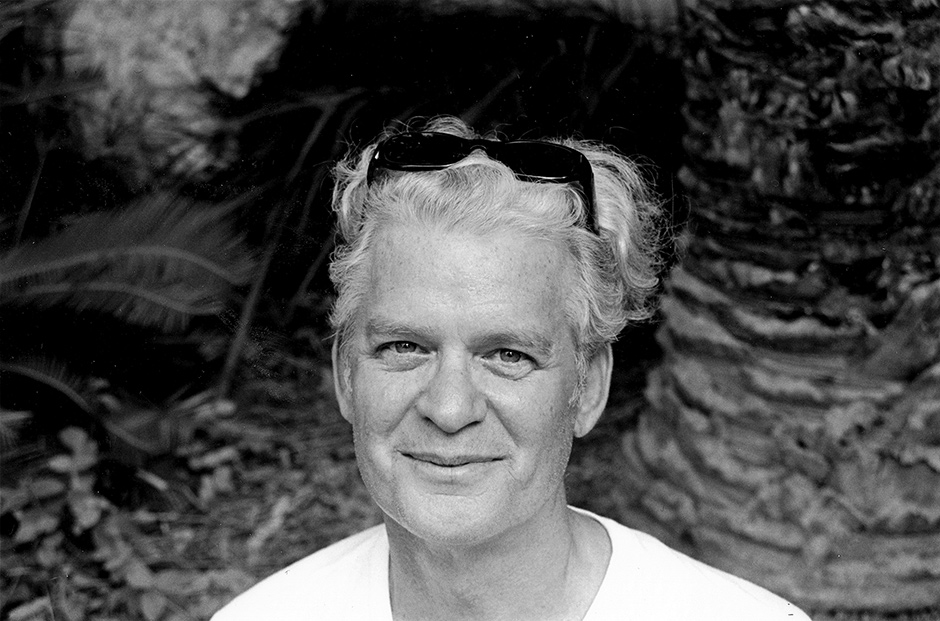

Smith was born in 1947 in Georgia, attended Phillips Exeter Academy and Duke University, and studied creative writing at Iowa. He lives now in New York City and Florida. Red Roads, his first collection, came out in 1987, when he was already forty, and many of the early poems have something post hoc about them, the songs of a man who’s come through. He’s a survivor, surprised to be one, always having escaped a situation, an addiction, a relationship.

“Honesty” (from Heroin and Other Poems)—which contains walk-ons by Poe, Anna Karenina, Kissinger, Ovid, and the Dalai Lama—features the refrain “it’s no good,” which has as referent pretty much everything. To exist in Smith’s poems is to be trapped, “snarled like a deer in a fence.” Imagining the scenarios described in the poem—such as “Poe kissing his child bride”—causes the speaker to “shiver with tension.” This state of “tension” comes up repeatedly. It’s in the content, of course—what else makes a poem?—and volumes such as The Palms (1994) and Before and After (1996) are finely turned disquisitions on the tension of family life, its strictures and structures (and tonally indebted, one might note, to Stanley Kunitz and Louise Glück):

In my family we’re all missing something,

something beautiful we once saw,

like a yellow carriage disappearing over a hill…

Sometimes what’s haunting or hunting the speaker is chemical addiction. Heroin and Other Poems (2001) is frank about being that rara avis, a rural addict, who “in [his] junkie days…kept a cattle herd.”

However, that Smith tells us he is “an intense person,” that he is “so lonely and intense, so/tense and energetic,” doesn’t mean much, except that the work continually locates techniques to show this tension, to contain and enact it. The word “tension” and its cognates—intension, extension, tenseness—derive from the Latin tendere, to stretch, and the poems are often radically strained, stretched affairs.

Like much contemporary American poetry, the work makes use of unlikely parataxis and juxtaposition (often between, say, grand abstractions and the excessively specific) to propel itself forward: “I got interested in religion, licorice/and banana popsicles which signified the unusual/figurations of universal import”; “there are cranberry bogs for sale/and rich partial distractions.” His lines often switch back on the reader, reworking our expectations for purposes comic, or sinister, or profound, or all three at once: “I drive by the graveyard to visit Mother//but she’s still not there”; “I’ve got time on my hands,/it won’t wash off.” “Where did you put//the thingamajig that was going to save you?” There’s a tragedy both ridiculous and plangent in a line like “I go where the fruit cups are.” He utilizes suggestive mistakes (“distinguished moments I mean anguished moments”) and ambiguities, and it seems a kind of legerdemain, to distract you as the pocket of your soul is being picked—or as your soul’s being jumped, as the title of Smith’s new book might suggest.

Advertisement

Many of Smith’s poems work because of the tension he engenders by mixing the physical and the metaphysical. His work reminds me of Allen Tate’s definition of “good poetry” as “a unity of all the meanings from the furthest extremes of intension and extension” (see his essay “Tension in Poetry”). In the field of logic, from which Tate takes his terms, “intension” is the internal content of a concept, and here includes the complications and connotations of metaphor and mental drift; extension is the literal statement, the range of a term or concept as measured by what it denotes or contains. (Tate notes astutely that there is an intensive–extensive scale on which every poet deploys “his resources of meaning.” “The metaphysical poet as a rationalist begins at or near the extensive or denoting end of the line; the romantic or Symbolist poet at the other, intensive end; and each by a straining feat of the imagination tries to push his meanings as far as he can towards the opposite end, so as to occupy the entire scale.”)

Smith weaves between what Tate would call extension and intension:

My wife’s in the kitchen melting plastic spoons,

I’m out back

coaxing the cat out of a mincemeat pie.

Symbolically in these matters we’re connected—

like captains on distant windjammers,

one on fire,

the other signaling for a second helping.

We can paraphrase these lines from “Red Cotton” logically: his wife is cooking, leaving implements by accident to melt against the hob or hot pan, and the speaker has found the pet cat trying to eat the pie, etc. But the import and strangeness of them is not for such easy reduction: they aren’t puzzles to be solved, or not quite. In another sense, on another plane, the lines mean what they suggest, mean what mood the imagery conjures: the world is weird and it feels like his wife is sitting in the kitchen, madly and methodically melting plastic spoons (and perhaps this also has a nod to drug addiction). Or his cat is actually baked in the pie, much as the four and twenty blackbirds were. There’s a suggestion that the marriage itself suffers from the mismatch the diction enacts. When one vessel is “on fire,” the other doesn’t signal help, as we might anticipate or hope, but for “a second helping”: greed trumps altruism. Though the poem leaps about conceptually, the whole thing is held together sonically with assonance: plastic—back—cat—matters—captains—distant—jammers.

When the poet tells us that we’re connected, symbolically, he’s referring to the marriage he and his wife have contracted, but he’s also implicating us, the readers. The ambiguities (though this seems too narrow a term for this type of open-ended phrase-making) enable the poem to run along on several tracks at once, as consciousness does.

Tate thought that being forced to read both intensively and extensively—in the logical senses of those terms—means we exercise the range of our full capabilities: “Our powers of discrimination are not deductive powers, though they may be aided by them; they wait rather upon the cultivation of our total human powers, and they represent a special application of those powers to a single medium of experience—poetry.” Smith’s poems require this special application, as they slip amphibiously outward and inward, flicking between the state of the world and the mental state, what he elsewhere calls “the inner life, salients/and extended peregrinations.”

There’s an exaggerated example of this in “Dengue,” where his technique—the diction, the sound effects and syntax—mimics veering from the outside, the factual, the clear-sighted world, to the inner realm of the symbolic, as if entering and exiting the delirium of fever:

Mosquito implanted little fleur-de-lis

probably in my right wrist unnoticed really

when the unwiped pump dumped energetic

wrigglers in the vein. A few days later

I put my head down on the table

and slept three hours. Fever a seething

hydrous wind that blew the house doors wide.

I sank in a scalding vessel suddenly caught

in the ice capades, the crew collapsed and

baldly illuminated, all souls skinned

and left rotting on a sunbaked portico.

I couldn’t talk or go outside or eat.

This is a heightened version—feverishly heightened—of what Smith continually does: here, the denoted logical lines—I put my head on the table and slept, I couldn’t talk or go outside or eat—direct and contrast the suggestive connotations, and the physical and metaphysical fuse into the dualistic experience of being mind and body. (Even the imagery folds in on itself: the fleur-de-lis refers to the physical appearance of the mosquito’s proboscis and its two sensory palps, which replicate the lower tripartite section of a fleur-de-lis, and I note that in Kate Greenaway’s Language of Flowers (1884), fleur-de-lis signifies flames, or “I burn.”)

Advertisement

“Dengue” uses alliteration, repurposes verbs, and exhibits major tension in diction and register, even in the space of a single sentence:

Swept in a clumsy current, basted, super-

factuated, raked by voices commemorating

the loquacity of drowned privateers and painters

whose work had been burned by the judges,

I lay on the bed panting.

The flights of thought, of the Latinate mind (super-factuated, commemorating) are pulled down into the Old English body, onto the Old English “bed,” where it pants (Middle English) like an animal. The diction returns us to a pre-modern state, back to the Eliotic brass tacks of birth, copulation, and death, panting on a bed like someone giving birth or having sex or dying.

Smith can construct a poem from mixing diction alone, can make, pace O’Hara, cocktails out of ice and water. His poems are adventures in register: “I got this wind//at my back, relatively/speaking….” Here’s how a lunchtime chat is described:

I gave him a sandwich and we sat on his front steps talking about the ruins of our lives. He harped on alignment and succulence, I spoke my piece about the universal buttering up going around.

Company is rare here though: the survivor’s note is mostly struck in solitude. As it was for Yeats, poetry for Smith is the social act of a solitary man. Loneliness is “a family art.” The trope recurs of being “a long way from home” (which again moves from the physical-geographical sense and ends in the metaphysical-existential sense) and the poems cast about unsuccessfully for how a soul might settle in the world, a body, a relationship, even in nature:

I don’t get it about the natural world.

Like, greenery,

without people in it, is supposed to do what?City sunlight, I say, how can you beat it—

the walk to the pool after work, shine

caught in the shopkeeper’s visor, bursts.

The lovely wrong-footing of that “bursts” sends the reader backward to try to work out where it fits. Is it the shine—which we’ve realized is a noun—bursting somehow, sparkling? Is it bursts of sunlight off the city’s windows? The sentence, the sense of the line, itself bursts, and the chime with “work” means it also sonically bursts onto the inner ear. Smith’s work is in tune with the city, which, like his poetry, “deharmonizes,” occasioning “juxtapositions both instructive and beautiful.”

Nature lacks something for Smith, a neon verve, the texture of mixture: he steps “back from the homespun,/the naturally dyed.” Nature is too brutalistic, too close to those Eliotic brass tacks. He hears a keening in the sound of the wind; it “grieves at the corners of/the house.” There’s no room for individuality:

Trees thrive in mass groupings

that close behind you and shudder

and stir complex imaginings

we are wholly unsuited for. Better

a quiet nook uptown. A room

with faded yellow light and Monk

on the piano.

Suspicious of any group undertaking, Smith proposes art as a way of following one’s own calling, of representing real emotion: it’s no accident that he chooses to reference the individualistic playing, the singular riffs and solos of our secular Monk, Thelonious. The poem ends, overstating it perhaps, “The buckle/and belting of life are beside the point.” Art, decorative, determinedly non-useful, the fripperies and fineries, is, for Smith, the point. (He can spell things out a little barely: “economic systems/rattled to dust. Only art/will last….”)

One of the finest pieces here, “Used to Be More One-Eyed Men,” combines Smith’s eye for the right detail with this theme of art’s value and virtue. It begins mid-rumination:

…used to be more one-eyed men,

more crippled men and obscure backward men

half-crazy from teasing….

(Note that “crippled,” in the physical sense.) What follows are scenes from the underside of American history, public and private. There’s frontier life, family life:

used to be horrible occurrences just over the ridge,

women mutilating dead enemies, men

pissing in another man’s eyes, used to be the grime

wouldn’t come off…

used to be the jealous uncle

still alive, plotting revenge, used to be

less pavement, villages without sidewalks…. [My ellipses]

The poem turns to how art is whittled out of circumstance: the descendent of a farmer who “fell in love with a town girl and never spoke of it” comes on his diary of “stilted confessions”

and understood he loved a woman,

used to be this was enough, a memory like this

passed down haphazardly from father to son, later

worked out in a story or a script, a grain of it alive

in the heart of one ambitious for fame

or simply peace, used to be you

could repeat this in your own life obscurely,

experience the tender insistence, the weird, crippled hope.

By the last line, the word “crippled” has traveled the wide arc of the poem’s anaphora, its various byways, and come back changed, changed to its metaphorical meaning. It has moved from the physical to the metaphysical, from the denoted to the connoted, and though art may not solve or salve a bodily injury, it keeps a memory, “a grain of it alive.” Art tends “the weird, crippled hope” that one might yet escape or explain or understand.

Not all of Smith’s poems work. Sometimes the shock value feels cheap, attention-grabbing: “Take the monkey, she said, and go.” He has a few tics, default postures that undermine a poem’s autonomy. He likes to end poems with a hyperextended simile, and sometimes these feel overworked, grand themes crowbarred awkwardly into specifics: “Time’s rusty chains held us as we leaned back into our solitudes like children on a barge hauling them downriver to their worthless foster homes.” There can be too much Whitmanian listing, such as in the overlong “Moon, Moon” or “Hollyhocks” or “As for Trees.” And he can very occasionally be flat and uninteresting: lines, like these, from “Delirious,” lack syntactic tension, and fail to revivify the dead idioms:

In Miami

not a moment too soon

the hookers

who don’t want to be alone yet

ask if I’d like a little morning massage

the sun’s rising

like someone stepping from a barroom fight

the pace is killing

He can also hit the odd off-note of sentimentality, when abstractions are not sufficiently embodied, and sound like a bad torch song:

the wind dying down

a softness in your wife’s face

reminding you of something

you thought you’d never forget.

At its frequent best, though, his poetry is—as he writes of “Turpentine”—an “upgrader//and extender of intensities,” a “sustainer/of paints and medicines.” It’s distilled, restorative, pungent. Turpentine, Smith declares, was applied by “old folks” to “cuts, scrapes,//to repair the body broken by falls/and gunshots,” to

Uncle Somebody risingfrom the swamp torn by a bear. You’d hear him

hollering, nothing particularly unusualabout it, a general claim, exaction of the universe

by a fellow traveler: Help me, Lord,or Quit, now, or just Ay-ee!

as one might say, raising the shade on Judgment Day.

The price the universe demands from a “fellow traveler” is high, and we hear it being exacted all the time. But it is typical of Smith’s cunning, wild, enervating writing that a further question is asked in that ambiguous phrase “raising the shade.” Is the Lord present who’s called on to “raise the shade,” to bring the ghost back to life, or is the “one” alluded to us, the reader, the voyeur who “raises the shade,” lifts the blind and watches Judgment Day come for Uncle Somebody? Is “Ay-ee” a resuscitating command or a scream of fear and despair? Such an agitation of meaning enlivens and makes true these often remarkable poems.