It was an oddity of growing up in the small Berkshire town of Faringdon in the 1950s that Lord Berners’s name was often mentioned. He was, in a way, a part of the landscape. A tall slender tower on a hill at the edge of the town was the goal of all our childhood walks, its red-brick walls rising scarily blank to a high-up viewing chamber and Gothic crown that showed above the surrounding pines. This was Lord Berners’s Folly, said to be the last great folly built in England, and stridently opposed by the town when it was first planned in 1934. Before long of course it was something to be proud of, and when Berners depicted it in his painting for a famous Shell poster it became an emblem of the town, its Eiffel Tower. It was opened with fireworks on Guy Fawkes Night 1935 and the guests were invited to “bring effigies of their enemies for the bonfire. No guest may bring more than six effigies.” It bore a characteristic notice: “MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC COMMITTING SUICIDE FROM THIS TOWER DO SO AT THEIR OWN RISK.”

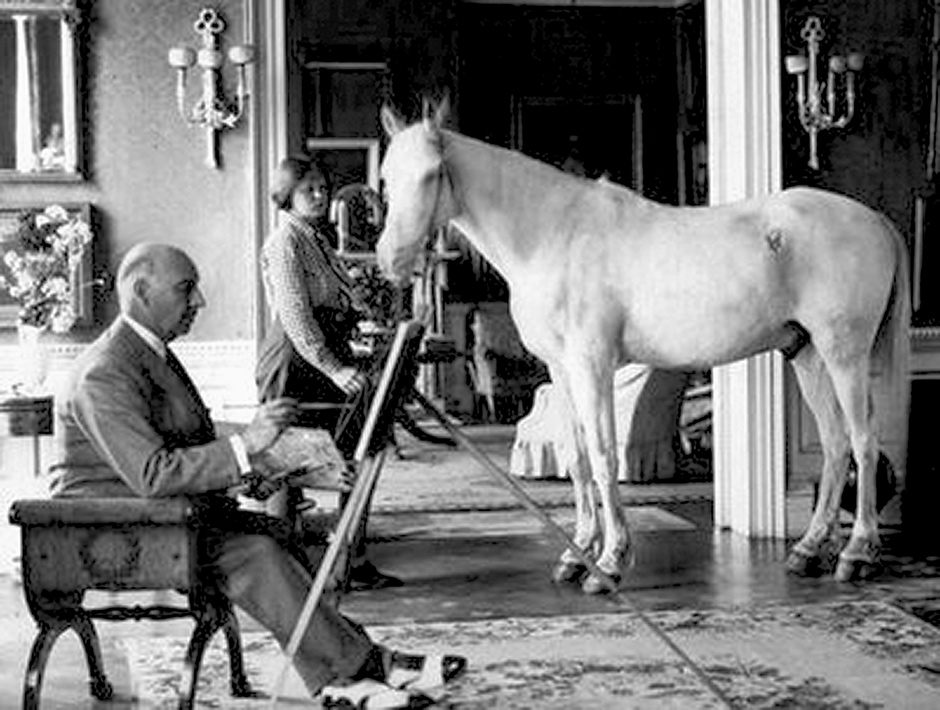

Berners, a distinguished composer, novelist, and memoirist as well as a prolific painter, was best known to us, as he had been for decades to the illustrated papers, as an eccentric. Around him anecdote, not discouraged by himself, proliferated and mutated. Extremely rich, he had made Faringdon House, his elegant Georgian mansion concealed beyond the parish church, a place of luxurious hospitality to artistic and society friends throughout the 1930s and beyond. Twenty years earlier a clued-in porter might have noted the arrival at our little train station of Salvador Dalí, Gertrude Stein, or Elsa Schiaparelli.

After Berners’s death in 1950 his much younger partner and heir, Robert Heber-Percy, maintained his traditions. He continued to dye the Faringdon pigeons all the colors of the rainbow, and made further surreal interventions in our placid rural scene. He installed the salvaged statue of “Africa” that looked down on the road into town on the north side—a swathed figure spoken of and described in guidebooks as a woman, but on close inspection of the chest quite clearly a man. It had just the Berners note of deadpan provocation, a sexual conundrum hidden in plain sight. Sofka Zinovieff records the rumor that the Folly itself was a birthday present from Berners to Heber-Percy, an outrageous phallic compliment disguised as an architectural caprice.

Their relationship was an attraction of opposites, the older man shy, stout, and bald, a depressive who sought refuge in frivolity and the creation of wittily sophisticated music; the younger, known for much of his life as “the Mad Boy,” lean, handsome, barely educated, recklessly physical, and sexually magnetic. Mainly Heber-Percy magnetized men, but he had flings with women, one of which produced a daughter. This is really the origin of Zinovieff’s book, since that daughter was her mother. The early part of The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me gives an admirable account of Berners’s colorful but hardworking career, and of the life he and Heber-Percy made together at Faringdon; it’s in effect a double biography, in which a story told before only from Berners’s perspective is seen from a new angle. Then, very fascinatingly, Zinovieff traces the complex aftermath of their story through subsequent generations.

The result is a study in unconventional relationships, enshrined in the setup at Faringdon House, in surprising marriages and rapid divorces, in the pursuit of pleasure and its darker undertow. A note of heartlessness is essential to the fun as well as the pain of this largely upper-class world. Faringdon itself is at the center of the book; it was Heber-Percy’s final but inspired piece of mischief to leave the house and its estate not to an expectant nephew, not to his daughter (who got nothing at all), but to his granddaughter Sofka, and the later chapters of her superbly illustrated book are a subtle reckoning with what such an inheritance might mean and entail to an independent-minded writer and anthropologist, responsive to the beauty and legends of the house, but dismayed by the demands and snobberies of the class system that had long sustained and defined it.

After his mother died in 1931, Berners felt free to start writing a memoir of his childhood in which he could speak frankly, if not always accurately, about her, and about the miseries and occasional joys of his own upbringing. First Childhood (1934) and A Distant Prospect (1945), about his time at Eton, trace the emergence of a sensitive aesthete from a background of philistine Shropshire gentry; the books are also a quite bold attempt to explain himself as both a depressive and a homosexual. The depression was there from early on—“Black care can sit behind us even on our rocking-horses.” Feelings of isolation and neglect fed the larger blackness, fits of accidie that long outlived their cause; the constantly concocted frivolity of his later life was as much a way of keeping his depression at bay as were the strictly maintained routines of writing, painting, and composing. When Faringdon House had to be closed down at the start of World War II, this sustaining ambience was destroyed and Berners, lodging fifteen miles away in Oxford, had a nervous breakdown and underwent Freudian analysis.

Advertisement

His school life was dominated by hatred for sadistic masters, aesthetic rapture caused by music and the discovery of Wagner, and hopeless adoration for certain boys—the memoirs give off an unusually strong sense, for a man in his fifties, of unforgiven cruelties and unforgotten humiliations. Berners describes his obsession with a beautiful boy called Longworth, a romance that seems about to reach an improbable fruition when Longworth invites Berners to join him for a cigarette on the roof and lies beside him in the moonlight: “Never before in my life had I seen such disturbing beauty in a human face.” With perhaps a “telepathic inkling” of his adorer’s feelings, Longworth throws his arm around him and draws him close. “Then a dreadful thing occurred. Almost before I knew what was happening I was violently sick.”

Berners always describes himself as someone without a chance as a lover, a person whose own body was at odds with his desires; but these accounts were written after he had settled down with Heber-Percy, and have perhaps a further private irony. His sexual life remains a possibly appropriate blank. Zinovieff says the two men were not viewed as lovers by the staff; and Mark Amory, in his 1998 biography of Berners, seems to credit the story of an unsuccessful trial weekend, after which Berners said, “Don’t go. You make me laugh. I don’t mind about the other.”

This would certainly square with Berners’s equanimity about his partner’s subsequent marriage, and later the installation of a boyfriend of his own at Faringdon House. Berners was loyal and generous, but surely not good at intimacy. The “Valse sentimentale” he composed for four hands suggests the most clumsy mismatch of the dancing couple. To some people indeed he seemed, in his charming way, not quite human—Siegfried Sassoon found him “consistently inhuman and unfailingly agreeable.” To Clarissa Churchill, a new young friend made during World War II, “his jokes were a defence against intimacy.” It fits with the pattern that Zinovieff, at early meetings with her grandfather Heber-Percy, found that “his character discouraged intimacy.” The admission of true feeling was not only bad form, it was a threat.

What strikes one more now, in the memoirs and in the short surreal novels Berners wrote after being psychoanalyzed, is the amused and unflustered prominence he gives to gay characters, perhaps more than any contemporary writer. Homosexuality, he writes, “is a subject that has been handled by the most highly esteemed authors of all times, from Moses to Proust, and sometimes, I may say, not without a certain degree of hypocrisy.” Berners himself was not a hypocrite; his high bohemian circle was rich in gay men and in others, like Heber-Percy, whose sexuality was more omnivorous. He was certainly wary of public queenery, refusing to appear at breakfast at an Amalfi hotel with the “Mad Boy”—Heber-Percy—in “a scarlet shirt, a blue jumper, green trousers and a yellow belt.”

Berners’s style was more the poker-faced hint, the wink through the monocle. In his perceptive short memoir of the novelist Ronald Firbank he confesses that at first he found his friend’s flamboyance “decidedly embarrassing.” In fact in both men pathological shyness existed in a complex relation with their need to draw attention to themselves, though it is not always easy to say where the involuntary merges with calculated performance. To Berners, Firbank was “strange, orchidaceous, incoherent, fantastic,” an idiosyncratic mix of the helpless and the willed.

It’s a shame that Berners never wrote an account of his life as a composer. The fascination of his music from the start was its un-English orientation, its detachment from both the melancholy late-imperial splendor of Edward Elgar and the burgeoning pastoral tradition of Vaughan Williams. In the 1930s his distinctive taste would align him with composers a generation younger, such as Constant Lambert and William Walton. He writes at a refreshingly Frenchified angle to his native scene, typical of his desire to startle, to amuse, and to prick pomposity. In 1916 he sought guidance from Stravinsky, who had a high opinion of his talents within their prescribed range. One of his most surprising pieces is among his earliest, composed that year, Three Little Funeral Marches—one for a statesman (ponderous), one for a canary (sweetly pathetic), and one for a rich aunt (a gleeful allegro). Some people found them an unseemly response to death in the midst of the war, but their ignoring of the war was no doubt part of their point.

Advertisement

Berners became known as the “English Satie,” which isn’t quite right but suggests his disconcerting wit and economy. The mainspring of his music is parody—after his Fantaisie Espagnole was performed (in the same program as the first British concert performance of The Rite of Spring) Constant Lambert remarked that it was now “impossible to hear most Spanish music without a certain satiric feeling breaking through.” Notable commissions followed: The Triumph of Neptune, choreographed by George Balanchine for Sergei Diaghilev in 1926; and A Wedding Bouquet, a ballet with a chorus singing text by Gertrude Stein, in 1937. The Fantaisie Espagnole seemed set to become standard repertory in the 1920s, but like these other beautifully crafted pieces it is now hardly played at all; perhaps the “satiric feeling” that animates them has also proved their limitation.

Berners inherited his title (he became the fourteenth Baron Berners) from a childless maternal uncle in 1918. His discreet early claim that “I inherit only the title, with a lot of taxes to be paid” proved incorrect; he was now seriously rich and free to create for himself the optimal conditions for both pleasure and work. He bought and beautified houses in both Rome (where he’d worked as an honorary attaché to the British embassy) and London’s Belgravia. Robert Heber-Percy, on the other hand, knew from the start that he would inherit almost nothing. Like Berners he came from an old Shropshire family, but he was a fourth son, with minimal prospects, and with almost no ability to concentrate.

The paradoxes of Heber-Percy’s childhood were formative: the uninhibited outdoor life of a big estate, which he would stick to till the end, and the regimented indoor life, whose piety and abstinence he emphatically rejected, while valuing into his old age the formal regularity of a well-run household. As the youngest child he was left behind by his elder brothers and furtively spoiled by his mother; he became a “daring show-off” to prove himself and attract attention otherwise directed elsewhere.

There was no chance of his getting into Eton or Harrow, but he found a place at the newly founded Stowe school, a vast country house of about the same size as the one he lived in at home, where he carried on with much the same sense of daredevil entitlement. His headmaster wrote about him: “He is a problem. Some people can’t succeed, but he can’t try.” Sending him on to a crammer at the age of sixteen, he observed that “fatigue appears to make his mind go perfectly blank at intervals. You will find his work startlingly bad, but I shall be greatly surprised if you do not like the boy himself.”

Similar objections were made, in a less friendly voice, by his superiors in the King’s Dragoon Guards, which he joined at the age of nineteen. There are very funny reports under different headings: “Energy:…lazy”; “Tact:…tactless”; “Leadership:…indifferent”; “Tactical knowledge:…scanty.” Laziness and indifference led swiftly to his expulsion; and after that he was let loose on what Zinovieff calls “the wild life of the city.” Within a year he would meet Gerald Berners at a house party, and then the course of the rest of his life was set. He was twenty and Berners was forty-eight. If he felt at home at Faringdon, it was in part, as Zinovieff suggests, because he behaved there like “a favoured first son on a country estate, but with the indulgence of an older man who was in love with him.” It was a magical adaptation of the preordained perspectives of family life and a happy deliverance from any conventional career.

Everyone in both their worlds was surprised. It “was the first time I had met civilised people,” Heber-Percy later recalled. But the civilization of Faringdon, with its celebrated warmth (“Faringdonheit” as one guest called it), its rich food (the signature Soufflé de Berners was made with brandy, eggs, cream, and crystallized fruit), and its glamorous, sexually unorthodox guests, was a thing apart. What Heber-Percy and Alice B. Toklas talked about over breakfast we will never know, but they probably got on fine, and there were certain parallels in their roles; “we did not share a single interest,” he said of Berners after his death, a special kind of tribute to a friendship. Still, the Faringdon of those years was a collaboration. They thought up ideas like dyeing the pigeons together but it was Heber-Percy who executed them. He became estate manager and during the war was officially Lord Berners’s “agent.”

There’s an eloquent photograph by Cecil Beaton that captures what happened next. Posed in the study that Berners used during the war as a bedroom, it places three unsmiling heads on a diagonal: at the top, Heber-Percy, leaning lightly against the bed and looking down at Berners, at the center of the picture, seated at a desk and reading a book in apparent unconcern, while sitting on the floor, her face half in shadow, is Jennifer Fry, now the Mad Boy’s wife. She alone looks out at us, an uncertain intruder in the world of the two men. Both the young people got on with Berners, but not with each other. After marrying her and bringing her to Faringdon, Heber-Percy’s cruel streak had emerged; he had repudiated her and locked her out of his bedroom. The marriage was effectively over.

As a writer Zinovieff has been doubly fortunate in her grandmothers. In Red Princess (2007) she explored the extraordinary adventures, sexual, political, and intellectual, of her father’s mother, Sofka Dolgorouky, a Russian aristocrat who fled the 1917 revolution, was interned by the Nazis, worked for the French Resistance, moved to England, yet was a card-carrying Communist to the end of her days. The most poignant parts of The Mad Boy are her investigation of the life of her English grandmother, another highly sexed and intelligent woman, caught up not in revolution but in the brittle dysfunction of British upper-class life.

The only child of a severe, wealthy, and secretly gay father and a beautiful but passive and neurasthenic mother, Jennifer grew up in the care of nannies (she’d had nine by the age of five) in a large and lonely-looking country house in Wiltshire called Oare. Her salvation was the last nanny, known as Pixie, with whom she formed the most enduring relationship of her life. (Such bonds with particular servants are a feature of this story.) She was attractive, adventurous, what was known as “a popular girl”; but was drawn recurrently to men who would treat her badly. After Heber-Percy she married the poet, editor, and cricketer Alan Ross, who seems to have been at once and continuingly unfaithful to her, though she maintained him financially for many years.

When Berners died, Evelyn Waugh wrote, “The Mad Boy has installed a Mad Boy of his own. Has there ever been a property in history that has devolved from catamite to catamite for any length of time?” In fact Hugh Cruddas, who had become a fixture at Faringdon toward the end of the war, was very unlike the Mad Boy: he was genial, helpful, and sweet to the point of masochism. Although he was made farm manager, his gifts were domestic; he was a fine, even overenthusiastic flower arranger and mixer of Bloody Marys, and his party piece was an impersonation of the Queen Mother: he was said “to actually become her.” He clearly excited the sadistic vein in Heber-Percy, who was soon making fun of him (“anything for a shriek!,” as Nancy Mitford said), and in time, when “Hughie” had put on weight and lost his boyish appeal, he was regularly bullied and humiliated in front of others by his friend.

At the same time, the Mad Boy took up with a young estate foreman, known as Garth. Thus he had “the indoor boyfriend and the outdoor boyfriend,” Garth being allowed in the house during the day, but not in the evening for meals. Such a situation, where both boyfriends were put at a disadvantage by the seigneurial Robert, says something that is revealing about class and (of course illegal) homosexuality in the period. At about the same time the writer John Lehmann had moved with his lover Alyosha, a former ballet dancer, to a cottage in Sussex. The devoted Alyosha contributed funds to its purchase, but he was never allowed into the drawing room, a ban he observed even after Lehmann’s death. What a world of fearful prohibitions and swallowed indignities it was.

The most terrifying master–servant bond Zinovieff describes is that between her grandfather and the German cook Rosa Proll, whom he stole from a friend and brought to Faringdon in the late 1950s. Through her brilliance the culinary heyday of the house could be recreated; but her ambitions extended far beyond the kitchen. In Rosa’s slavish devotion to Heber-Percy, Zinovieff discerns “an affinity with totalitarianism” (the chapter about her is called simply “The Nazi”). She swiftly banished all the indoor staff, and did all cooking, cleaning, washing, and mending herself, with military exactness.

She then terrorized the outdoor staff, patrolling the grounds with a large dog. “Trespassers on the estate became a thing of the past”; but there were still trespassers on the affections of her master. Against the feeble Hughie she could count on Heber-Percy’s collaboration: “Robert was known to pour a bottle of red wine over his lover at dinner and Rosa once poured cold water over Captain Cruddas’s head from the first-floor landing.” There was a good deal of slapstick, and the reader will cheer when Robert pours a bottle of milk over the head of Rosa herself.

The great challenge to her supremacy came in 1985 when at the age of seventy-four Heber-Percy suddenly married his old friend Lady Dorothy Lygon, always known as Coote. Coote, known for her loyalty, kindness, and discretion, had been a close friend of Berners, as she had been of Waugh, who romanced the Lygon family into the Flytes of Brideshead Revisited. Her father, Lord Beauchamp, had been forced into exile by a major gay scandal, and she was sensitively attuned to the sexual unorthodoxy of Faringdon. She lived in a little house in the town, but was a constant presence at the big house.

Always said to be unmarriageably plain when young, Coote perhaps lost her head, or her memory, on getting her old friend’s proposal. The omens were bad. The furious Rosa, relied on for a wedding banquet, came up with three plates of ham sandwiches. When the couple returned from a gloomy Venetian honeymoon, they found that Rosa had gone, leaving the previous week’s dirty dishes in the sink. Coote’s married life echoed Jennifer’s before her, spurned like an unwelcome guest, but now having to do all the housework as well. In fact the elderly couple were “utterly incapable of looking after themselves,” and within weeks Coote had gone back to her cottage and Rosa returned triumphant.

After Heber-Percy’s death in 1987, Rosa transferred her loyalty dynastically to Sofka Zinovieff, who found the time that she spent at Faringdon with her young friends still dominated and determined by Rosa, a figure both slave and tyrant, who declared she would only leave the house in a coffin. But she was at last ejected alive—she met her death, described here in a bleak vignette, knocked down at dawn by a truck on the ring road as she was walking, as she did each day, several miles to her job as cook to another family. She was eighty-five, and in her will left over half a million pounds to a children’s charity.

If I dwell on her story, it is because it typifies the way Zinovieff has drawn from obscurity the dozens of lives whose threads converge in this house over nearly a century. Her cast list is vast, and topped by world-famous stars, but among them and behind them come others, creative, dependable, amusing, unhappy (often that), like names in an old visitors’ book caught moving again in their dance to the music of time. The Mad Boy is an absorbing as well as original book, which replaces the monographic vectors of biography with something more curious and multifarious, nonetheless brought into a haunting and satisfying shape.

And if the Folly remains the emblem of the era and the place, we see that something of enduring interest happened in this rural backwater eighty years ago. It is magical to me to find here a photo of the old walled gardens that my mother and I went through each Friday in my childhood to buy produce from the estate; two men stand there smiling, Lord Berners, in a trilby, his arm in a sling, and a smaller figure in a dark coat, eyes shadowed by the brim of his cap, who is Igor Stravinsky. In his conversations with Robert Craft, Stravinsky is asked about Berners, and recalls this October weekend in the late 1930s, the “crystal bed” he slept in and the roan horses he rode. He responded especially to an atmosphere that was “not exclusively traditional”:

Meals were served in which the food was of one colour pedigree; i.e., if Lord Berners’s mood was pink, lunch might consist of beet soup, lobster, tomatoes, strawberries…. My wife Vera used to send him saffron dye from France, and a blue powder which he used for making blue mayonnaise.

One notes both the odd suggestiveness of the word “pedigree,” as if aristocracy were sublimated into aesthetics; and the evident feeling that one-colored meals were a good idea. It was silliness pursued in all seriousness.