Max Beerbohm has always been a minority taste. “There are only fifteen hundred readers in England and one thousand in America who understand what I am about,” he estimated. This did not dismay him. On the verge of being forgotten, he always seems to have the good fortune of being rediscovered and championed by those with a taste for invigorating prose. One such enthusiast, the critic F.W. Dupee, wrote:

Rereading Beerbohm one gets caught up in the intricate singularity of his mind, all of a piece yet full of surprises…. That his drawings and parodies should survive is no cause for wonder. One look at them, or into them, and his old reputation is immediately re-established: that whim of iron, that cleverness amounting to genius. What is odd is that his stories and essays should turn out to be equally durable.

Beerbohm himself claimed, “What I really am is an essayist,” and, to the degree that one values essays, one is apt to consider him not only durable but indispensable.

In her 1922 piece “The Modern Essay,” Virginia Woolf singled out Beerbohm as an exemplary practitioner, while also nailing the paradox of his art. Calling him “without doubt the prince of his profession,” she went on:

What Mr Beerbohm gave was, of course, himself. This presence, which has haunted the essay fitfully from the time of Montaigne, had been in exile since the death of Charles Lamb. Matthew Arnold was never to his readers Matt, nor Walter Pater affectionately abbreviated in a thousand homes to Wat. They gave us much, but that they did not give. Thus, some time in the nineties, it must have surprised readers accustomed to exhortation, information, and denunciation to find themselves familiarly addressed by a voice which seemed to belong to a man no larger than themselves. He was affected by private joys and sorrows, and had no gospel to preach and no learning to impart. He was himself, simply and directly, and himself he has remained. Once again, we have an essayist capable of using the essayist’s most proper but most dangerous and delicate tool. He has brought personality into literature, not unconsciously and impurely, but so consciously and purely that we do not know whether there is any relation between Max the essayist and Mr Beerbohm the man. We only know that the spirit of personality permeates every word that he writes.

Today, when memoirs and personal essays stand (rightly or wrongly) accused of narcissism and promiscuous sharing of private information, it does well to ponder how Beerbohm performed the delicate operation of displaying so much personality without lapsing into sticky self-disclosure.

His readers learned everything about his temperament and response patterns—rigorously self-analytical, he was onto all his idiosyncrasies—but next to nothing about his background, finances, affairs, or spouse. Some of that reticence regarding women had to do with his gentlemanly code: he drew almost no caricatures of women either. Aware that he shied away from confession, he wrote, “Personally I admire the plungingly intimate kind of essayist very much indeed, but I never was of that kind, and it’s too late to begin now.” The fact is, he could never make himself the rugged hero; what interested him more was tracking his odd turns of consciousness.

Beerbohm, born in 1872 to a middle- class mercantile family, came to precocious prominence in the 1890s, while still an Oxford undergraduate, when he was taken up by the Yellow Book crowd. This group of self-styled Decadents, which included Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde, made a cult of beauty, artifice, and masks. Socially he fit in, being a good-humored listener with a tolerance for eccentricity, though Wilde, disconcerted by Beerbohm’s imperturbable manner, asked a mutual friend: “When you are alone with him,…does he take off his face and reveal his mask?” Max remained loyal to the Decadents’ belief in beauty and personae. But a firm grounding in common sense prevented him from swallowing the Decadents’ desire to shock, and he considered Wilde’s florid self-presentation somewhat silly.

“Only the insane take themselves quite seriously,” he said. His antennae for vanity, grandiosity, and self-delusion governed from the start. In his initial essays on dandies and rouge, his touch was so deft that he seemed simultaneously defending and mocking artifice, as when he complimented the dandy Beau Brummell for his dedication to dress:

And really, outside his art, Mr Brummell had a personality of almost Balzackian insignificance…. I fancy Mr Brummell was a dandy, nothing but a dandy, from his cradle to that fearful day when he lost his figure and had to flee the country….

Beerbohm himself was impeccably turned out, but distanced himself in other respects from Dandyism. In her study The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm, Ellen Moers, summarizing an impertinent piece he wrote about Wilde, remarked: “Max had already mastered an art which would serve him for the rest of his career: the art of satirizing, lambasting, insulting with impeccable decorum; the art of getting away with it.”

Advertisement

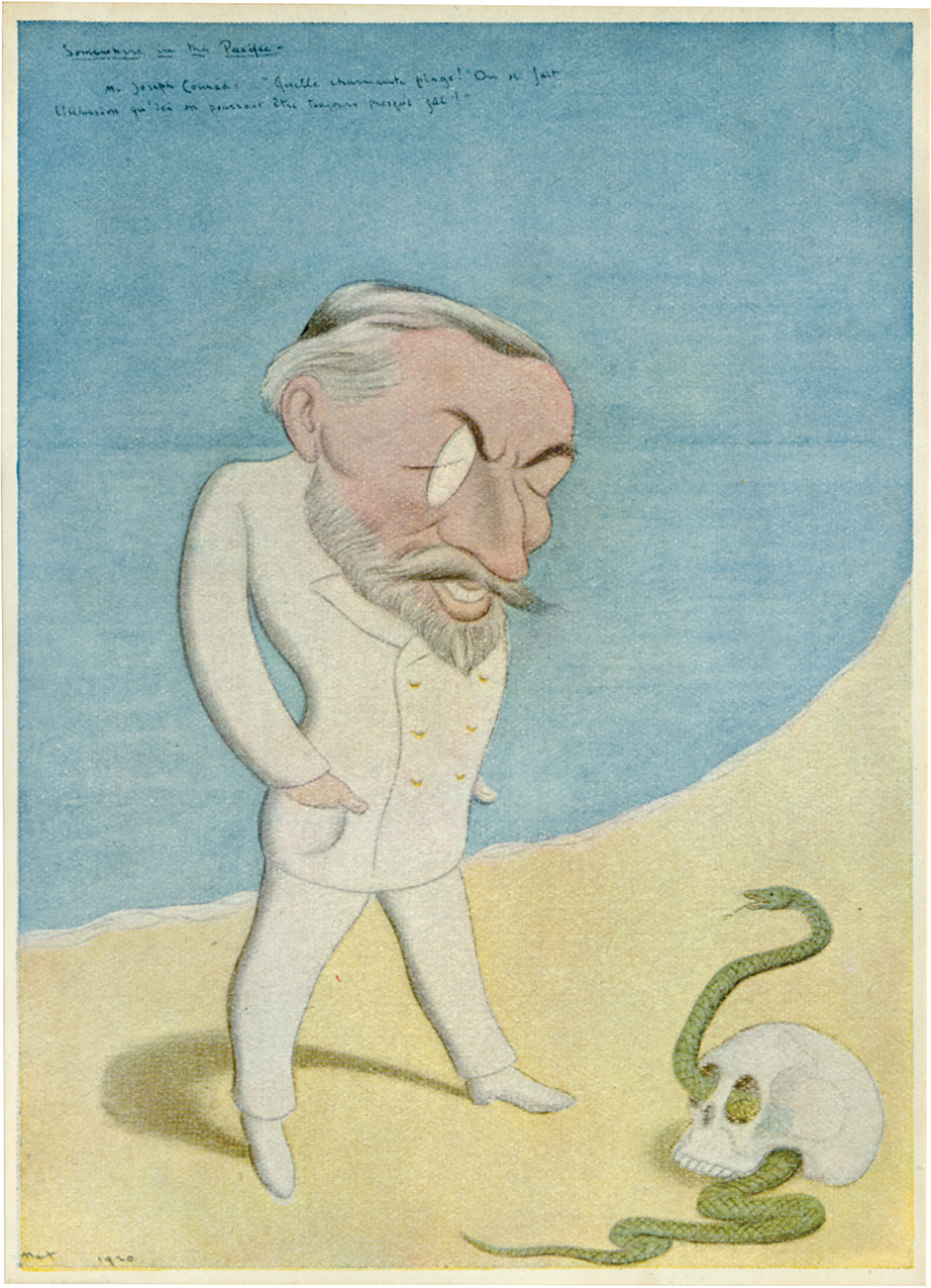

Nowhere was this balancing act between affection and aggression more evident than in his caricatures. In “The Spirit of Caricature,” he defended himself from accusations of mean-spiritedness, saying the point of caricature is exaggeration:

The most perfect caricature is that which, on a small surface, with the simplest means, most accurately exaggerates, to the highest point, the peculiarities of a human being, at his most characteristic moment, in the most beautiful manner.

This description applies equally to Beerbohm’s prose, designed to convey economically the drollest possibilities.

Part of his humor derived from a tendency to portray himself as behind the times. In 1895, a mere five years after entering Oxford as a freshman, he declared: “Already I feel myself to be a trifle outmoded. I belong to the Beardsley period…. Indeed, I stand aside with no regret.” Prematurely middle-aged, he was always standing aside—or pretending to.

Beerbohm was preoccupied with the past. “There is always something rather absurd about the past,” he wrote. “For us, who have fared on, the silhouette of Error is sharp upon the past horizon.” Much like Charles Lamb, who confessed he was too fond of retrospective glances, Beerbohm’s mind clung to the old days, even the period before he was born. A tongue-in-cheek tribute to the Prince of Wales, “King George the Fourth,” showed his fascination with the royals, especially after they had been stripped of their power and reduced to a “life of morbid and gaudy humdrum.” He felt sympathy for these ceremonial, leisure-plagued dinosaurs, fated to look on. He himself preferred to be a watcher, not a player. His Max persona drew on the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century essayist’s classic tropes: the idler, the spectator, the outsider, the bachelor (or later, the non-parent).

This observer sensibility helped prepare Beerbohm for his next role, that of drama critic. His older half-brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, an actor and theatrical impresario, had taken him to plays and introduced him backstage. He had even engaged Max as his secretary on a barnstorming tour of America, though Max, with his fastidious concern for proper wording, proved too slow at answering his brother’s correspondence. One side effect of Max’s theatrical immersion was that he fell in love with a succession of actresses. Another was that he seemed to everyone (but himself) the logical candidate to succeed George Bernard Shaw in 1898 when the latter resigned his post as drama critic of The Saturday Review.

Shaw had recommended the younger man, at twenty-five already a rising literary figure, as his successor, signing off with the famous sentence: “The younger generation is knocking at the door, and as I open it there steps sprightly in the incomparable Max.” This label, “the incomparable Max,” stuck to Beerbohm all his life, not entirely to his liking. There was generosity but also condescension in the compliment: Shaw would never have spoken of the Incomparable Leo, Virginia, or Henrik. Beerbohm repaid the favor by writing ambivalent reviews of Shaw’s plays. “Mr. Shaw is always trying to prove this or that thesis, and the result is that his characters (so soon as he differentiates them, ever so little, from himself) are the merest diagrams.”

Beerbohm confessed reluctance about his new occupation in his maiden column: “Frankly, I have none of that instinctive love for the theatre which is the first step towards good criticism of drama.” But he took the job, needing the money. He would go to several plays, then compose his copy on Thursday. “Thursday was the day on which I did it; and the doing was never so easy as I sometimes hoped it might be: I had never, poor wretch, acquired one scrap of professional facility.”

Compounding the problem was that he was a picky theatergoer, and when he liked something, all the worse. “I have the satiric temperament: when I am laughing at any one I am generally rather amusing, but when I am praising any one, I am always deadly dull.” His collected theatrical criticism, Around Theatres, is still entertaining, but it comes alive most when he is playful. Such, for instance, is his hilarious review of Sarah Bernhardt’s memoirs. After quoting the actress’s passionate denunciation of capital punishment, and her witnessing the execution of a friend, the anarchist Vaillant, he comments: “You, gentle reader, might not care to visit an execution—especially not that of a personal friend. But then, you see, you are not a great tragedian.” This is classic Beerbohm: resisting the domineering, flamboyant personality (Wilde, Bernhardt, Shaw, or Max’s brother Herbert), meanwhile bonding with the phlegmatic English reader.

Advertisement

One of his funniest essays, “Quia Imperfectum,” takes on Goethe, that titan who “has more than once been described as ‘the perfect man.’… But a man whose career was glorious without intermission, decade after decade, does sorely try our patience.” Beerbohm enumerates:

He was never injudicious, never lazy, always in his best form—and always in love with some lady or another just so much as was good for the development of his soul and his art, but never more than that by a tittle.

Beerbohm loves to seductively align with his readers, by invoking some secret wish for skepticism or spice. In his essay “How Shall I Word It?,” which satirizes letter-writing manuals, Beerbohm characterizes the average reader’s response: “He longs for—how shall he word it?—a glimpse of some bad motive, of some little lapse from dignity.” Yet as often as Max conspires with the reader, he just as frequently predicts that readers may not go along with his thin-skinned position. He presents himself readily as isolated from the common response. In “Laughter,” he notes: “A public crowd, because of a lack of broad impersonal humanity in me, rather insulates than absorbs me. Amidst the guffaws of a thousand strangers I become unnaturally grave.” Elsewhere, he snaps awake from the dream of kinship with readers by sudden distancing: “But perhaps you, reader, are not as I am. I must speak for myself.” The point is to engage with the reader, warmly or cheekily.

Addressing the reader had already become antiquated in Beerbohm’s day, and so it suited his behind-the-times persona. It also gave him freedom to jettison subjects whimsically, like saying about the 1880s: “To give an accurate and exhaustive account of that period would need a far less brilliant pen than mine.”

The taking up of a serious subject in a grave tone, only to abandon it with a shrug of inadequacy, is exemplified by the opening of “Laughter”: “M. Bergson, in his well-known essay on this theme, says…well, he says many things; but none of these, though I have just read them, do I clearly remember, nor am I sure that in the act of reading I understood any of them.” He then explains how he is always resisting the philosophically fashionable: “It distresses me, this failure to keep up with the leaders of thought as they pass into oblivion.” (The sting in the tail of that sentence is priceless.)

Much of his comedy stemmed from contrarian, impious impulse: his asserted dislike of going for walks (“Even while I trotted prattling by my nurse’s side I regretted the good old days when I had, and wasn’t, a perambulator”), or, conversely, his defense of arson (“Nothing is easier than to be an incendiary. All you want is a box of matches and a sense of beauty”). Daring the reader to disagree, he gives permission to entertain one’s own curmudgeonly thoughts. That Beerbohm never set himself up as a pundit, but only as “a man no larger than themselves,” to quote Virginia Woolf’s useful phrase, made the vinegar more palatable.

In the twelve years that he covered the theater scene, he also led an exhaustingly active social life. Max was a sought-after guest at dinner parties and galas. No one knew what it cost him to keep up this gregarious charm, to be always “on.” His energy flagging, he lived for times when he could go off by himself to some seaside town in winter, tending his inner life. He even wrote a one-act play, A Social Success, about a man who plots unsuccessfully to become socially ostracized. But like his protagonist, Beerbohm could never say no to importuning hosts.

Finally, he made a change that shocked everyone. In 1910 the longtime bachelor got married to an American actress, Florence Kahn, quit his critic’s post, left London, and at age thirty-seven took his wife and himself off to a little house outside Rapallo, Italy. There he lived, frugally, for the better part of the next forty-four years in semiretirement from society, though friends and relations would visit on their Italian vacations. Max had not been joking when he said he yearned for the quiet life.

The ten years following his move to Italy saw his most productive writing period. First he completed his novel, Zuleika Dobson, a comic romp about a femme fatale who causes hordes of Oxford undergraduates to drown themselves. Zuleika was his most popular book. It was followed by A Christmas Garland, his wicked set of literary parodies, and Seven Men, his bittersweet fictional portraits of men of letters, mostly unsuccessful. All three works are exquisite; but it is a pity that Beerbohm is most known today as a novelist, parodist, and caricaturist, when his greatest achievement, I would argue, is as an essayist. The two collections he published after leaving England, And Even Now and Yet Again, contain the ripest fruit of his essayistic art. (With mock conceit, he had titled his youthful, thin debut collection The Works of Max Beerbohm. Thereafter, he tagged each subsequent gathering of essays as an afterthought—More, And Even Now, Yet Again.)

Having escaped the London social scene, Beerbohm could articulate the strain that geniality had been for him. In “The Fire,” he described the onus of being a weekend guest:

For fifteen mortal hours or so, I have been making myself agreeable, saying the right thing, asking the apt question, exhibiting the proper shade of mild or acute surprise, smiling the appropriate smile or laughing just so long and just so loud as the occasion seemed to demand…. It is a dog’s life.

Lord David Cecil, his attentive biographer, summarized Beerbohm’s approach:

Irony is its most continuous and consistent character; an irony at once delicate and ruthless, from which nothing is altogether protected, not even the author himself. Ruthless but not savage: Max could be made angry—by brutality or vulgarity—but very seldom does he reveal this in his creative works. His artistic sense told him that ill-temper was out of place in an entertainment, especially in an entertainment that aspired to be pretty as well as comic. His ruthlessness gains its particular flavor from the fact that it is also good-tempered. On the other hand it is not so good-tempered as to lose its edge.

In “Kolniyatsch,” he mocks the British admiration for moody, Dostoevskian writers, by inventing his own Slavic literary celebrity:

At the age of nine he had already acquired that passionate alcoholism which was to have so great an influence in the moulding of his character and on the trend of his thought…. It was not before his eighteenth birthday that he murdered his grandmother and was sent to that asylum in which he wrote the poems and plays belonging to what we now call his earlier manner.

Note the perfect-pitch parody of literary toadyism. Max was more at home with Trollope (“He reminds us that sanity need not be Philistine”) and Henry James.

If we now take for granted the centrality of sexuality and passion in human behavior, Beerbohm’s reluctance to play those cards would seem to issue from another, more stoical understanding of life. His indifference to convincing us that he was a man of strong libido or emotion seemed in line with his unwillingness to play up to the reader: “But how exasperating, how detestable, the writer who obviously touts for our affection, arranging himself for us in a mellow light, and inviting us, with gentle persistence, to see how lovable he is!”

Beerbohm’s syntax derived from the study of Latin, in which he had prided himself as a schoolboy, and which he considered essential “to the making of a decent style in English prose.” It was initially a prose steeped in the Edwardian manner: long unbroken paragraphs, sentences hemmed with semicolons, mock-learned Latin and Greek, aphoristic conclusions. Over time it became looser and more direct. Though always attracted to polished prose (“I love best in literature delicate and elaborate ingenuities of form and style”), he also grasped the danger of fussiness. In Oxford he had rebelled against Walter Pater’s treatment of “English as a dead language,…wherewith he laid out every sentence as in a shroud—hanging, like a widower, long over its marmoreal beauty….”

While Dupee said that Beerbohm “wrote with a kind of conscious elegance that has since become generally suspect,” Max drew the line at ornate obscurity. “Too much art is, of course, as great an obstacle as too little art.” He saw vocal quality as “the chief test of good writing. Writing, as a means of expression, has to compete with talking.” Beerbohm’s own prose was conversational: one more reason he kept addressing the reader. Its formality seemed a politeness, making the impudence acceptable.

Back in London, Beerbohm’s popularity had irked Ezra Pound, who included a sneering, thinly veiled reference to him in his 1920 poem “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley”:

BRENNBAUM

The skylike limpid eyes,

The circular infant’s face,

The stiffness from spats to collar

Never relaxing into grace;

The heavy memories of Horeb, Sinai and the forty years,

Showed only when the daylight fell

Level across the face

Of Brennbaum “The Impeccable.”

Pound’s anti-Semitism was misdirected, since Beerbohm was not Jewish. He told interviewers he would have gladly claimed Jewish heritage (both his wives were Jewish) but as it happened, he had none. Ironically, Pound ended up in Rapallo, Italy, not far from Beerbohm’s home. They did not become friends.

Beerbohm returned to England during both world wars. Unlike the more feckless P.G. Wodehouse, he knew enough not to putter around the garden with fascists nearby: “A foreign country in war-time,” he wrote, “is an uncomforting place to be in. One wants to be where the English language is spoken, and English thoughts and feelings are expressed.” The expatriate had become more stalwart a patriot than ever. “I have never met anyone more stubbornly English than Max,” S.N. Behrman reported. He was invited by the BBC to give a series of radio talks, which were so well received that Beerbohm became, improbably in middle age, a national figure. Rebecca West wrote: “I felt, when I was listening to them, that I was listening to the voice of the last civilized man on earth.”

Beerbohm wrote the talks with the listening ear in mind. The sentences had fewer dependent clauses; the diction was plainer; this was not just accommodating the broadcasting medium, but the direction his prose had been evolving. Max shied away, as ever, from triumphalism: “There is much to be said for failure. It is more interesting than success.” He sifted politics, using what he had called his “Tory Anarchist” perspective. Fearful of angry labor embracing the Soviet example, he acknowledged that no injustices would ever be righted unless the injured parties protested, citing women’s suffrage as example. He had opposed military adventurism and imperialism. Domestic service should be abolished, he wrote in “Servants.” He was, as he characterized himself in that essay, “Loth to obey, loth to command.”

He was not one “ever seeking ‘sensations’ and experiences.’” His preface to A Variety of Things challenged: “I am a quiet and unexciting writer.” In fact he could be deliciously exciting, if irony was your meat. He pretended to regret its use: “I wish, Ladies and Gentlemen, I could cure myself of the habit of speaking ironically. I should so like to express myself in a quite straightforward manner.” But Beerbohm knew that “all delicate spirits, to whatever art they turn…assume an oblique attitude towards life”; and obliqueness suited him. He put it succinctly in a 1921 reply: “My gifts are small. I’ve used them very well and discreetly, never straining them: and the result is that I’ve made a charming little reputation. But that reputation is a frail plant.”

Virginia Woolf, who so appreciated him, nevertheless expressed reservations:

One takes for granted what one can only call Mr Beerbohm’s perfection, and then, as if one could swallow perfection and still keep one’s critical capacity unsated, one looks about for something more…. For a second he makes his own perfection look a little small.

Still, perfect is not bad.

I have mentioned that Shaw’s calling him “the incomparable Max” irked him. It exempted him unfairly. Beerbohm wrote:

Years ago, G.B.S., in a light-hearted moment, called me “the incomparable.” Note that I am not incomparable. Compare me. Compare me as essayist (for instance) with other essayists. Point out how much less human I am than Lamb, how much less intellectual than Hazlitt, and what an ignoramus beside Belloc; and how Chesterton’s high spirits and abundance shame me….

He wrote less, but showed his drawings in London galleries, and their sales helped support his and Florence’s modest Italian life. His neighbors reported seeing him laughing to himself—he still found much absurd, though in “Laughter” he maintained that one laughs less as one ages. Beerbohm frequently drew in books, wrote counterendings, or invented far-fetched dedications. He would occasionally show these comic interventions to guests, but he did it for the most part simply to amuse himself. The creative spirit that springs gratuitously from play, in children and adults, still manifested itself, though now he had no need to display it. He had reverted to being an amateur, in the sense of doing something for love, and love alone.

In 1951 his wife Florence passed away. Max turned to Elisabeth Jungmann, a long-standing devotee, for help with the funeral arrangements, and Elisabeth promptly moved in and took care of him in his remaining years. Just before he died, in 1956, Max married Elisabeth, willing her the house in Rapallo and his estate.

He had not liked where the modern world was going; and the years had only strengthened his attachment to the past. But he could still defend that position good-humoredly, as when he twitted the Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti for hating museums:

With the best will in the world, I fail to be frightened by Marinetti and his doctrines…. How on earth is anyone going to draw inspiration from the Future? Let us spell it with a capital letter, by all means. But don’t let us expect it to give us anything in return. It can’t, poor thing; for the very good reason that it doesn’t yet exist, save as a dry abstract term. The past and present—there are two useful and delightful things. I am sorry, Marinetti, but I’m afraid there is no future for the Future.

If there is to be any future for Beerbohm’s remarkable writing, it will come about through preserving all that is exquisitely wrought and laugh-inducing in it.