To understand Picasso’s major works of the early 1930s we must go back to his youth at La Coruña, on Spain’s north Atlantic coast, where his father, Don José, was director of the local art school. Don José Ruiz Blasco had three children: Pablo and two girls, Lola and Conchita. Over Christmas 1894, Conchita, aged seven, contracted diphtheria. Serum had been ordered from Paris but weeks would pass before it arrived. Fourteen-year-old Pablo so adored his sister that he vowed to God that he would never paint again if her life were spared. He did paint again and the serum failed to come in time. Conchita died on January 10, 1895.

According to Françoise Gilot, Picasso had never divulged the secret of his broken vow to anyone but the women in his life. It was a warning that they, like Conchita, would be sacrificed on the altar of his art, a fate that all of them, except for Gilot, would share.

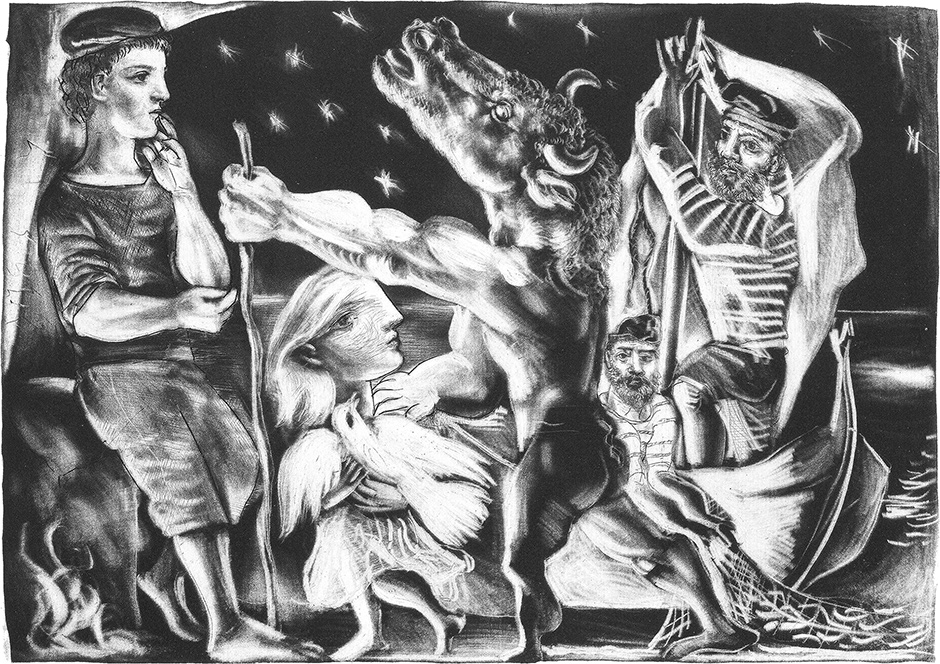

The broken vow also set off his votive reaction to the disasters that would afflict him in the 1930s. This knowledge casts new light on the meaning of his work, not least on his two greatest prints, the Blind Minotaur and Minotauromachie, both of which are in the collection of the newly reopened Musée Picasso in Paris.

In August 1934, Picasso embarked on his last trip to Spain. Although he was doing his best to divorce his wife, Olga, he took her and their son Paulo with him. Since Olga became a Spanish citizen on marrying Picasso in 1918, a divorce would have to be issued in Spain before being granted in France. This explains why he accepted an invitation from the fascist gastronomic society GU to stay in San Sebastián, the chic beach resort, where he would encounter José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange, and his sidekick Ernesto Giménez Caballero. The trip also involved seeing a number of bullfights in Madrid, Toledo, Burgos, and Barcelona.

Within weeks of returning to Paris, Picasso started work on the Blind Minotaur, a print that commemorates his lifelong obsession with his eyesight. He was immensely superstitious and would ward off his fears in his work. In the Blind Minotaur he turned to a votive act—an expression of intense devotion, in this case to his sister Conchita. Sure enough she is at the heart of the print, albeit endowed with the face of Marie-Thérèse Walter, his mistress since 1927, while he had become increasingly estranged from Olga. Conchita is running toward a young man on the left: the artist as he would have looked at the age of fourteen, the year of Conchita’s death. She is seemingly in flight from the men on the boat, about to take her across the River Styx, on the right.

Picasso may well have had another source of inspiration for this print. In his Montmartre days, some thirty years earlier, he had been fascinated by a local art peddler called Léon (“père”) Angély, a retired legal clerk of limited means. He was known as a dénicheur (a spotter)—ironically since he was completely blind. Nevertheless, Angély spent his days going from one atelier to another, buying and selling works of art. Guiding his steps was a girl who described to him whatever he was “shown.”

Angély’s inspired speculations fizzled out after World War I. He was obliged to sell off his Picassos, Modiglianis, Utrillos, and much else before he died in 1921. That Fernande Olivier mentions Angély’s visits to the Bateau Lavoir—the building in Paris where Picasso lived and worked between 1900 and 1904—in her memoir of her time with Picasso suggests that Angély may have been a source of inspiration for Picasso’s print in which the Minotaur refers to the artist.

Gijs van Hensbergen—author of an excellent book on Guernica —has also pointed out Picasso’s reverence for Saint Lucy, the patron saint of the blind whom many Spaniards held in superstitious awe. This fourth-century martyr, who was in fact Sicilian rather than Spanish, had had her eyes gouged out by Diocletian’s militia. By the thirteenth century Saint Lucy had become a cult figure throughout Europe. Hence echoes of her legend in the Blind Minotaur and Minotauromachie.

One of Picasso’s erudite poet friends might well have told him about the role—small but significant—that Saint Lucy plays in Dante’s Divine Comedy, when Dante begins to ascend the mountain of Purgatory, which emerges from a lake. On the lake’s surface he sees a radiant boat floating on angels’ wings carrying the souls of the redeemed. Dante soon falls asleep and upon waking is told by his guide Virgil that Saint Lucy has brought them to the gates of Purgatory.

Advertisement

In October 1934, while still working on the Blind Minotaur, Picasso was horrified at the news of a revolt by miners in the coalfields of Asturias. Troops from Madrid under the command of General Franco used the utmost brutality to restore order. Approximately 1,300 were killed and 40,000 arrested, some of them tortured. This murderous response to the revolt appalled Picasso, who had hitherto strived to stay above the political fray. In later years, he would be embarrassed about the time he had spent with fascists in San Sebastián that summer, and would maintain that he had run away from the Falange and jumped on a train to Paris.

In fact, Picasso had stayed on in Spain, possibly to see Juan Belmonte, arguably the greatest torero in history. Although he had been badly gored the previous week, Belmonte appeared in the bullring at San Sebastián on September 2. By September 4 Picasso was in Barcelona for an interview with the local newspaper before returning to Paris. Nevertheless, the revolt in Asturias would once and for all determine Picasso’s left-wing allegiance. His anguish would help generate the two great prints that are the focus of this article.

The 1934 insurrection prompted many native artists and intellectuals to leave Spain, among them Salvador Dalí, who fled for Paris on October 6. As Dalí’s memoirs record, he crossed the border with the help of an anarchist cab driver who carried the flag of the newly declared Republic of Catalonia, as well as the Spanish flag in case the Republic fell to government forces, which indeed it did only ten hours after its inauguration.1

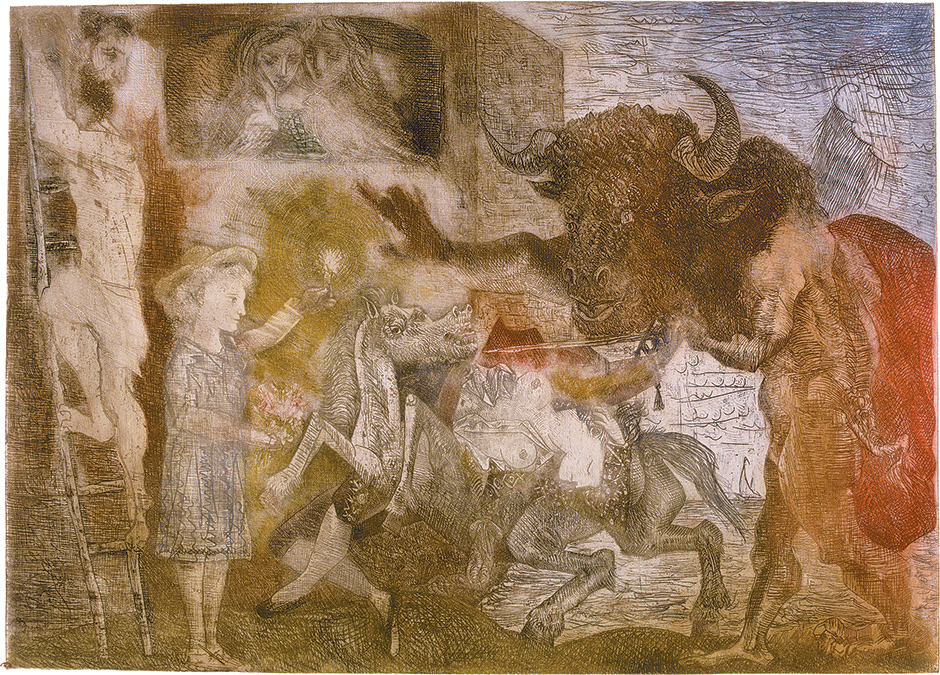

On March 23, 1935, Picasso embarked on what is unquestionably his most celebrated print, Minotauromachie. Once again he visualizes himself as a Minotaur, but—in contrast to the Blind Minotaur, so permeated with death as well as blindness—Minotauromachie recasts Picasso’s mythical alter ego as a figure of immense, albeit flawed, power.

Shortly after envisaging Minotauromachie, Picasso painted a large, somewhat bland landscape with figures, which bears no relation to anything he had ever done: La Famille (March 29, 1935). He seemingly intended the style to reflect the dim genre paintings of his youth. This uniquely uncharacteristic work turns out once again to be an ex-voto. Picasso had turned his back on modernism in order to think his way back to his childhood, and his vow never to paint again if his sister’s life were spared. In La Famille his mother clutches baby Conchita. Standing between her and the father is little Pablo and his sister Lola. The desolate landscape evokes the countryside behind La Coruña. It also evokes the painful winter of Conchita’s death in 1895, the season of the broken vow.

La Famille was an exorcism. It also signaled an abandonment of painting. Now Picasso could go ahead with Minotauromachie. The setting is the Minotaur’s legendary habitat on the island of Crete—hence the sea and the inclusion of a distant sailboat. But given the central references to bullfighting, we also seem to be in Spain.

As in so many previous bullfight images by the artist, Marie-Thérèse plays a central part in Minotauromachie, appearing as a wounded and near-to-death matadora. She is, again, bare-breasted and splayed across the back of her dying horse. This time, however, she is pregnant. Although seemingly lifeless, her black-clad arm reaches up and manages to cling to a sword pointed at the horse’s head. The horse’s entrails pour out of its belly, in contrast to Marie-Thérèse, who bares her pregnant stomach to the Minotaur.

Does Olga figure in this print? Not explicitly. As Picasso remarked to me twenty years later at a bullfight apropos a badly gored horse being dragged off: “These horses are the women in my life.” The hideous horse in Minotauromachie might well be her. Olga had become the focus of his hatred. As he worked on it, she had wounded the artist where it hurt most. She had had her lawyers put seals on Picasso’s studios in Paris and in the country, and on everything pertaining to his art: brushes, paints, and canvases.

At center left stands a young girl holding a light. She represents Conchita and her presence is central to the meaning of the composition. Conchita illuminates Minotauromachie. The Minotaur stretches out his right hand to grasp her light but he fails to reach it. The flame represents the art Picasso had vowed to abandon if Conchita lived. In Minotauromachie he is unable to grab the emblem of his votive obsession. His broken vow would never be fully redeemed.

Advertisement

The 1933 sculpture that Picasso ultimately chose to have placed over his grave at Vauvenargues is known incorrectly as La femme au vase. She is of course Conchita and she is not holding a vase but a torch, as she does in Minotauromachie. True, this figure does not represent a seven-year-old; Picasso preferred to immortalize Conchita as a grown woman. She would reappear as a child elsewhere in his work. In Guernica (1937), she is the girl holding a torch. When this masterpiece was shown at the Spanish pavilion of the Paris World’s Fair in 1937, it was flanked by a concrete version of the bronze Conchita that would preside over the artist’s grave.

Besides Conchita’s lamp, there is another source of light in the top right corner of Minotauromachie: lines of light from the Mithraic sun rain down on the nape of the Minotaur’s neck. In his misery Picasso seemingly invokes the Mithraic sun as well as the Mithraic bull. Mithra—who in the Persian tradition was the sun god—was sacred to Picasso. When he moved to Cannes twenty years later, he hung a Mithraic emblem on a studio wall. When questioned about this sunburst ringed with spiky rays, he admitted that Mithraisim fascinated him. Bulls had to be sacrificed to Mithra. It was in this spirit that he attended bullfights. He was also aware that there were connections between Christianity and Mithraism, and that some Christian festivities derived from Mithraic ones.

There is a reference to this link on the left side of the print. The Christ-like figure climbing a ladder looks apprehensively across at the rays of Mithraic sunlight in the opposite corner. This figure has also been identified as Picasso’s father, Don José, and indeed the artist once said:

Every time I draw a man, it’s my father I’m thinking of, involuntarily. For me, a man is Don José, and will be all my life. He wore a beard, and every man I draw I see more or less with his features.2

Don José came from a line of distinguished priests and hermits. Picasso was proud of having had a great uncle who had lived as a celebrated hermit. Was he out to exorcise the piety of his ancestors? Might the Christ-like figure threatened by Mithra’s rays be a mocking allusion to the deity he had been brought up to revere and never entirely renounced?

Minotauromachie raises a number of questions, but characteristically, the answers Picasso gives and the explanations suggested by a variety of evidence are riddles. Far from clarifying the meaning of the work, the artist kept it to himself. This print reflects the complexity and despair of his life at this time. A cri de coeur.

Last of all, what are Marie-Thérèse’s two sisters doing at the window, upper left, with a pair of Picasso’s father’s pet pigeons in front of them? They play a passive role in this complex drama. Like us, the girls are witnesses. That surely is their significance. Picasso has subtly included onlookers in his picture.

When Picasso finally ceased obsessing over this print is unclear. According to an entry in the diary of Marga Barr, wife of Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Picasso was still at work on it on June 24, 1935. Marga had accompanied her husband to Paris while he was assembling loans for his great Picasso retrospective in New York, which was due to open the following year. As she observed:

“Imagine! [Picasso] has stopped painting!” It is true. Picasso is nervous. Only when he feels like it does he work on his Minautoromachy etching.

Picasso takes [Alfred] to his old apartment on rue La Boetie; all the drawers and cupboards are tied with string and legally proscribed with large, stamped clots of red sealing wax. Picasso shows this to [Alfred] with a certain pride, insisting again and again, “Look! Look what they’ve done to me!”3