There are figures in French history who tower like monuments. Saint Louis, the Capetian king, a symbol of justice, Joan of Arc, warrior and martyr, and Henry IV, the great peacemaker, are three unmistakable paragons who personified a certain idea of French greatness. Oddly enough, Henry IV’s first wife, Marguerite of Valois, remembered as Queen Margot, also enjoys a high place in the popular imagination, although she had no political influence and her life was often threatened in the era’s turmoil; unlike her sister-in-law, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, she never wore the halo of martyrdom.

In France, nonetheless, she remains a popular presence in mass-market history magazines; five motion pictures have been made about her; she has been the subject of numerous biographies, some serious, while many others are far more fanciful and primarily focus on her amorous appetites and her “black legend.” In the aftermath of the beheading of her lover, Boniface de la Môle, it was said that she bought his head from the executioner and had it embalmed, and that during her lifetime she carried the hearts of her dead lovers in the pockets of her capacious dresses.

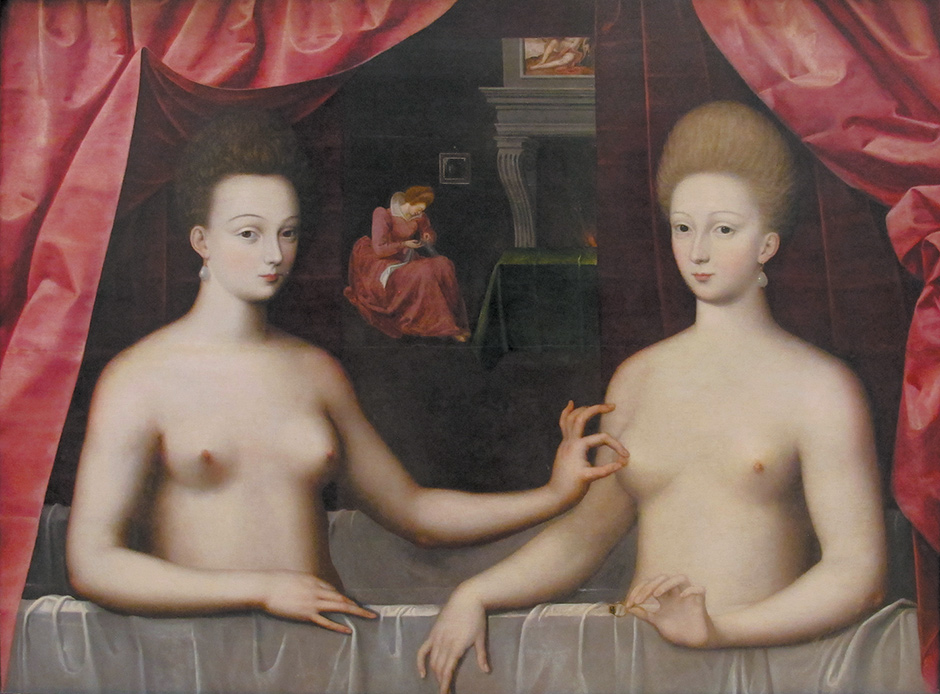

Certainly, Marguerite of Valois (1553–1615) had such a singular and surprising life that it could hardly fail to capture the interest of later generations. To begin with, she was the last member of the Valois dynasty (1328–1589), France’s most dazzling royal family. The Valois king who personified the French Renaissance was Francis I, the patron of Leonardo da Vinci, Benvenuto Cellini, and Andrea del Sarto. We owe to him the châteaux of Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain-en-Laye outside Paris and Chambord and Blois in the Loire valley. What’s more, Marguerite lived in the second half of the sixteenth century, dramatic years that were as glorious as they were bloody—glorious because of the cultural glow conferred upon them by the first great writers and poets of the modern era, Montaigne, Brantôme, Ronsard, du Bellay; bloody because of the violence and cruelty of the seemingly interminable French Wars of Religion.

Marguerite was five years old when her father, Henry II, died of a lance wound to the eye sustained at a joust. This marked the beginning of the end for the House of Valois. Henry’s three surviving sons each succeeded to the throne but none, whether because of physical frailty, weakness of will, or sheer laziness, ever truly ruled as king. It was their mother, Catherine de’ Medici, who governed the kingdom for most of that period. Her eldest son, Francis II, married Mary Stuart and died at the age of sixteen, a year and five months after ascending the throne. The second eldest, Charles IX, became king at age ten and died without legitimate issue at age twenty-three, leaving the crown to his younger brother, Henry III, who had neither the requisite wisdom nor the strength to exert any sort of authority over a nation riven by hatred between Catholics and Protestants. Henry III died childless.

One might have hoped that the marriage of Marguerite—sister to the three kings—to her Huguenot cousin Henry of Navarre in 1572 would bring about a reconciliation between the two religious factions. Instead, the wedding was stained just five days later by the terrifying Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre that left more than three thousand Protestants dead in Paris and put the young queen in an untenable position: the Huguenots, her husband among them, suspected that she had been aware of the plot against them, while the Catholics regarded her with distrust because she refused to abandon her husband after the tragedy.

Pulled first to one side then the other in the years that followed, she took part in various plots but was ultimately spurned by both sides. She then took refuge in a fortress in Auvergne, in central France, where she lived for almost twenty years in a state of internal exile that looked very much like captivity. The assassination of her sole surviving brother, Henry III, in 1589, set off the final crisis.

In the absence of a direct heir, the crown fell to Henry of Navarre. But the civil war raged unabated. The new king was forced to fight on for another four years before he was able to enter his own capital city. That was when he decided to abjure Protestantism: his famous declaration, “Paris vaut bien une messe” (Paris is well worth a mass), put a de facto end to the fighting. Henry IV had conquered the throne and was crowned king in 1594. Now he needed to put his conjugal affairs in order.

His marriage with Marguerite had produced no offspring. That outcome was hardly surprising given the lack of physical attraction between husband and wife and the infrequency with which they shared the same bed. Now, however, they were in agreement on one crucial point: their marriage had to be dissolved. The annulment would allow the king, already the father of a multitude of illegitimate children, to establish a lineage. The queen was therefore willing to be “unmarried” in order to allow another woman to take her place, provide the king with heirs, assure the future of the new dynasty, and facilitate a return of peace.

Advertisement

The woman who replaced her was Marie de’ Medici. Thereupon, in what was perhaps the most astonishing phase of her career, instead of fading away Queen Marguerite experienced twenty years of veritable splendor. Once the marriage was dissolved, the ex-spouses became the best of friends. The new queen, Marie, was inexperienced. It was said she was awkward and ignorant. So Henry IV asked Marguerite to teach her the customs of the court. Since he valued her skill in projecting the image of royal dignity and wished to show her the greatest marks of respect, he also entrusted her with responsibility for receiving ambassadors: in short, she once again had an important position at court and, even more surprising, she became an intimate of the royal family. The dauphin, the future Louis XIII, often came to see her and called her “Maman ma fille” (Mama my girl). Upon her death in 1615, she was sincerely mourned. According to the secretary of state, Pontchartrain, she was “full of kindness and good intentions for the welfare and the repose of the State.”

Mourned and not forgotten. The publication of her memoirs in 1628 brought a surge in interest. No prince or princess of the royal family had ever before written anything so personal, described family quarrels so openly, or provided so much information about the rulers of the time. Moreover, Marguerite wrote in a vivid, often startling language that pointed forward to Saint-Simon, the great diarist of the court of Louis XIV and the Regency that followed. Her memoirs were so popular that they were reprinted several times through the course of the century. Then the curtain fell.

As an authentic historical figure and as a memoirist, Marguerite vanished during the eighteenth century. If anyone still spoke of her at all, it was only to keep alive a scandalous and meretricious legend that focused on her lust, disorderly life, lavish spending, and immorality. As the French Revolution loomed, her memory suffered in particular from a groundswell of hostility toward queens, flamboyant princesses, and courtesans that culminated in the explosion of hatred for Marie Antoinette. The First French Empire was to prove no kinder to exceptional women, for Napoleon ratified the revolutionary principle of the juridical inferiority of women. And yet, thirty years after the fall of the Empire, Marguerite made her comeback.

The most plausible explanation for that unexpected revival is a novel by Alexandre Dumas published in 1844, in which, dexterously blending fact and fiction, he transformed a frozen image into an impetuous, unforgettable, popular character. Out of Queen Marguerite, he created Queen Margot. But she wasn’t really his own invention: Marguerite had become fashionable again, first of all because she was being read. Four new editions of her memoirs appeared between 1823 and 1842, as well as a substantial selection of her letters. Stendhal made her the idol and inspiration of Mathilde de la Mole in The Red and the Black. (In the novel, the de la Mole family are descendants of Marguerite’s lover.) It’s the memory of the queen of Navarre that gives Mathilde the “superhuman courage” to place the head of Julien Sorel, her guillotined lover, “upon a little marble table…and [to kiss] his brow.” And finally, Marguerite was the inspiration for two operas, Ferdinand Hérold’s Le Pré aux clercs (The Clerks’ Meadow), with a libretto by Prosper Mérimée, and Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots. (The Valois princesses seemed to inspire composers. Marguerite’s elder sister, Elisabeth, who was married to Philip II of Spain, is the heroine of Verdi’s Don Carlos.)

As for the nineteenth century’s more general revival of interest in the Renaissance, that can be attributed to a yearning for escape from a period in which dull materialism triumphed and exasperated true artists. How could anyone suffocating under the rule of Louis Philippe, the bourgeois king, help dreaming of a century marked by a taste for pomp and festivities, set against a backdrop of warfare, duels, intrigues, and treason? Balzac chose to rehabilitate Catherine de’ Medici in a novel that was largely ignored. Dumas had better luck, choosing Marguerite of Valois for the first in his series of historical novels. As befitted a skilled feuilleton writer who never mistook himself for a historian, Dumas tried above all to create characters who draw the reader in, frequently at the expense of subtlety and accuracy.

Advertisement

In his narrative, Catherine de’ Medici turns into an implacable and malevolent character while Charles IX is a bloodthirsty lunatic. Dumas makes a shining hero of Henry of Navarre. His depiction of Margot is more nuanced. He portrays her as sensual, adventurous, and yet practical. He also endows her with qualities of mind and presents her as better educated than her husband and brothers. Dumas doubtless took inspiration from an anecdote related by a number of contemporary observers: the young princess was said to have been the only member of her family capable of answering the Polish ambassadors in Latin upon their arrival at court. It is amusing to note that a revolutionary pamphleteer, Sylvain Maréchal, virulently opposed to the emancipation of women, proposed a law in 1802 that would have forbidden teaching girls to read, arguing that “if the first wife of Henry IV, Marguerite of Valois, hadn’t known how to write she might have been less amorous.”

Above all, though, Dumas’s Margot is no distant princess: she is a realist, determined to back her husband because, as she says, “it is the duty of a wife to share in her husband’s fortunes,” without letting that keep her from her escapades. Merry, mischievous, quick-witted, she has a common touch that appeals to ordinary people. The novel ends when Margot is only twenty-one, with a long and agitated life still before her. The popularity of the novelized history of Marguerite of Valois has never waned since it first appeared. In France, there has been an unbroken chain of editions up to the present day, three of them in the past ten years.

The story told by Dumas is good-natured, improving Queen Margot’s reputation. Over the years, the queen has continued to tempt filmmakers, biographers, and journalists, but they have interpreted her story in an increasingly dubious fashion. Margot became a nymphomaniac in the 1950s, in particular in a very widely read book by Guy Breton. In Patrice Chéreau’s 1994 film La Reine Margot, she chased relentlessly after men until, in the end, she was viciously attacked by her brothers. It would be difficult to make anything more insidious, anything less historically accurate. However, recently following the lead of the historian Éliane Viennot, books have been published that cleave closer to historical truth and depict a more complex and interesting character.

The latest work is actually a double biography: Nancy Goldstone has chosen to treat the life of Marguerite alongside that of Catherine de’ Medici. The decision was shrewd because, until Catherine’s death, the mother never gave an inch in wielding power over her daughter. Still, the book’s title, The Rival Queens, is surprising inasmuch as it takes a certain degree of equality to create a rivalry. Whereas Catherine, in her role as regent first and later through sheer force of character and the extraordinary authority that she exercised over all her children, had always terrorized her daughter. After the tragedy of Saint Bartholomew’s Day, it became clear to Marguerite that her mother wouldn’t hesitate to sacrifice her if it served her purposes, and she never entirely overcame the fear that Catherine inspired in her.

One of the challenges facing any historian of this period is the sheer profusion of themes that need to be handled. Just a few examples: the extreme complexity of the dynastic situation, aggravated by the scheming and intrigues of a violently divided royal family; the repercussions of the civil war; the international tensions that sprang from the rivalry between Spain, France, and England; the uncertainty surrounding the possible marriage of Queen Elizabeth—for twelve years Catherine nursed hopes of seeing her married to one of her sons, and she didn’t give up that dream until the death of the youngest. What makes Goldstone’s biography so enjoyable is that she manages, thanks to the clarity of her presentation, to lead readers through this labyrinth with a sure and steady hand.

Goldstone displayed the same qualities in her previous books. She is a popular historian whose writing is based on very serious research, with a gift for telling the most complicated tale in vivid, accessible prose. In The Rival Queens as in Four Queens, her book set in the thirteenth century, a time of chivalry and crusades, or in The Lady Queen, a portrait of the fourteenth-century queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily, she delights in unraveling the most drastic family entanglements in periods of violent insecurity.*

Another characteristic of her work is the importance she gives to the physical appearance of her subjects. When she wants to make the point that Catherine lacked charisma, she does not go into wordy analysis. Instead she simply describes her entry into a town:

When Catherine and Charles IX entered in procession, many of the townspeople looked right past the cloth of gold and the triumphal arch and the jeweled crowns and saw a very short, corpulent older Italian woman dressed all in black who ate and talked and walked incessantly accompanied by an unhealthy-looking, puerile boy who obediently parroted her commands. They were not a pair who inspired confidence.

She also makes good use of primary sources—the reports of ambassadors, especially the extraordinarily well informed Venetian ambassadors, who wrote in a strikingly direct manner, as well as the memoirs and correspondence of the era—and quotes extensively to illuminate her text. Here is Marguerite in her mother’s apartment, just hours before the Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre:

The Queen my mother…bade me go to bed. As I was taking leave, my sister seized me by the hand and stopped me, at the same time shedding a flood of tears: “For the love of God,” cried she, “do not stir out of this chamber!” …The Queen…called my sister to her and chid her very severely. My sister replied it was sending me away to be sacrificed.

The queen mother, implacable, refused to retreat and Marguerite was forced to retire. “As soon as I reached my own closet, I threw myself upon my knees and prayed to God to…save me; but from whom or what, I was ignorant.” (She was not harmed.)

Here is Marguerite’s brother King Henry III, his arms ringed in coral bracelets, “ordinarily dressed as a woman…exposing his throat,” surrounded by his companions, the mignons, “frilled and curled with their crests lifted, the crinkles in their hair…and covered with violet powders and odiferous scents, which smell up the streets, squares and houses they frequent.”

Goldstone sketches a very convincing portrait of Queen Marguerite. She sees in her an unusual and oddly liberated woman in spite of the pressures to which she was subjected. That she was sensual there can be no doubt, and she was frequently passionately amorous, but at the same time she was guided first and foremost by her religious fervor and by her political loyalty to her husband, whose life she saved in the aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre. The most telling example of her rectitude is the fact that Henry of Navarre himself asked her to draw up the brief for his defense when he was charged with taking part in a conspiracy. She acquitted herself so intelligently in this task that he was freed on the spot.

Finally, Goldstone underscores Marguerite’s love of reading, which allowed her to put up with years of solitary life with considerable equanimity:

My captivity and its consequent solitude afforded me the double advantage of exciting a passion for study, and an inclination for devotion, advantages I had never experienced during the vanities and splendor of my prosperity.

This spirit of independence, this inner freedom, this genuine intellectual capacity all explain the degree to which Goldstone is tempted to see in her a precursor to the feminist movement.

I think we should resist the temptation to see Marguerite as a feminist avant la lettre. The concept can hardly be applied to a sixteenth-century princess. Under the ancien régime, rank and wealth counted for more than gender. But from the French Revolution until the years that followed World War II, sex was decisive, because for all the talk of the equality of men, women possessed no civil rights at all. An illiterate French peasant could vote; Marie Curie could not.

Nothing comparable could be said about the sixteenth century, when royal princesses had the right, both by birth and by talent, to play important political parts. Two women, Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands, and Louise of Savoy, mother of Francis I, negotiated the Paix des Dames (Peace of the Ladies), as the Treaty of Cambrai was also known, putting an end to the war between Francis I and Charles V in 1529. In the following generation, two half-sisters, Mary Tudor and Elizabeth, reigned successively over England while Catherine de’ Medici held sovereign sway over France. But such power was not available to Marguerite of Valois. She proved incapable of bringing about a reconciliation between Huguenots and Catholics because she was caught up in incessant conflicts of loyalty, while the fact that her marriage remained barren led her to agree to leave her place on the throne at the side of Henry IV.

Ironically, it was the dissolution of that marriage that brought her the happiest years of her life. “Against all the odds,” wrote Goldstone, “she had survived the murderous brutality of her family and her times.” She kept her title of queen; by now she was independently wealthy. Henry IV had returned her dowry and, more important still, she had succeeded in overturning her mother’s will, which disinherited her in favor of an illegitimate son of Charles IX. With no one to answer to, she continued to take lovers in spite of the fact that she had turned from a lovely young maiden into an aging woman so fat that it was said that “there were many doors through which she could not pass.”

Most important of all, she had the wit to surround herself with a refined court, an entourage of poets and musicians, in striking contrast to the mediocre courtiers of Marie de’ Medici. Finally, Marguerite, faithful to her Valois blood, built herself a superb home, directly across from the Louvre, on the Left Bank, where the École des Beaux-Arts now stands. Her gardens extended to the rue du Bac in a park that was open to the public. The palace is long gone, but the queen’s memory is inscribed in the Parisian cityscape. The long parallels of the rue de Lille, rue de Verneuil, and rue de l’Université still mark, four centuries later, the stately allées of the park of Queen Margot.

—Translated from the French by Antony Shugaar

-

*

Four Queens: The Provençal Sisters Who Ruled Europe (Viking, 2007) and The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily (Walker, 2009). ↩