Last year in a Pew poll, most American Catholics (72 percent) said they want their priests to be married. I don’t know how many saying this realize that there are already married priests in the Roman Catholic Church. Probably not many—and this is no accident, as the priest-sociologist D. Paul Sullins writes in Keeping the Vow. The married priests are advised not to draw attention to themselves. Their most direct contact with the laity, as pastors of a parish, was for a long time forbidden. A concentration of more than two of them in one diocese was discouraged, so they were spread around to keep them exceptional, not the norm. Eastern Rite churches were forbidden until the time of Pope Francis to ordain married priests in the West.1

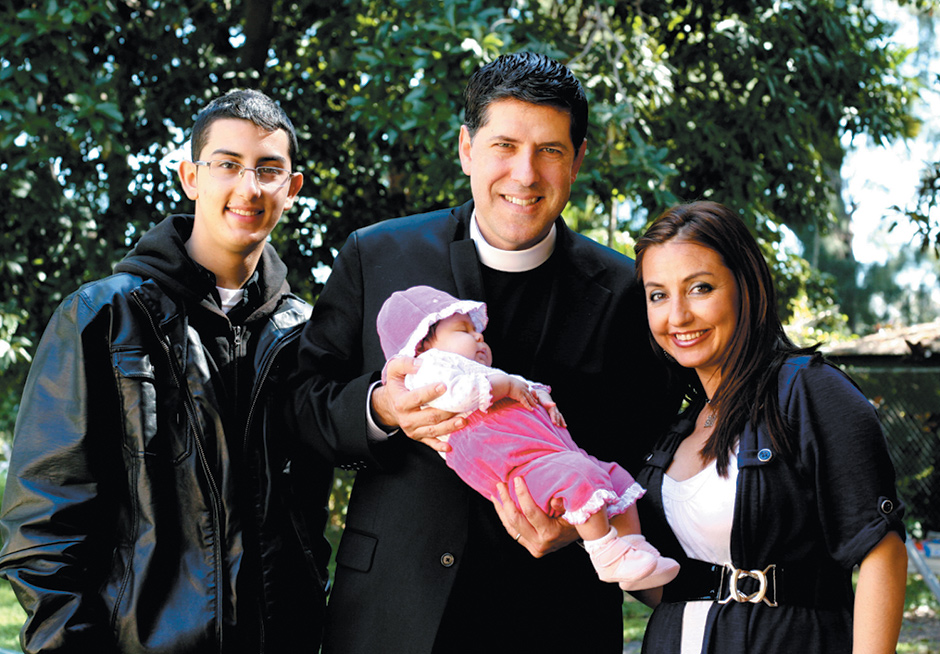

Roman Catholic married priests come in two sorts, one by long historical circumstance, the other by recent deliberate action. The former group, “Uniates,” is made up of priests from Eastern Rite churches that maintained union (hence their name) with the papacy. They were allowed to keep their wives, a normal practice in the Eastern church, in order to protect the papal tie. The second group, called “Pastoral Provision” priests, is made up of married Anglican priests who convert to Catholicism and are ordained again in the Roman church while keeping their wives. It is surprising, at first glance, that this privilege was granted by the very conservative Karol Wojtyła, Pope John Paul II, in 1980, and it was broadened by his equally conservative successor, Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, Benedict XVI, in 2011 (for England) and 2012 (for the United States). This looks odd because any Catholic loosening of the celibacy requirement is supposed to come from the left.

It has sometimes been suggested by naïfs that this would help the ecumenical movement by bringing Anglicans and Catholics closer together. But that was far from the actual effect and papal intent. The aim was a divisive one, to widen a rift among Anglicans and solidify Catholic opposition to Anglicans. To see why this is so, consider both terms used of Anglican conversion to the Catholic Church.

Conversion

Truly ecumenical actions do not stress conversion. An example of this was the Second Vatican Council’s confession of Catholic sins against the Jews. That was effected by a formidable number of Catholic priest-theologians from Jewish families. They pushed for passage of the document Nostra aetate, which recognized the eternal validity of the Jewish covenant.2 The official church no longer claimed that Christianity had superseded the Jewish religion. Some of the Catholic priests who worked for this long-overdue development did not refer to themselves as converts from Judaism. Like Saint Paul, they said they were still and always Jews. Paul VI, uncomfortable with the council bequeathed him by John XXIII, considered dissolving it rather than changing the condemnation of the Jews. (He also went against his own commission’s findings rather than give up the condemnation of contraceptives.)

Contrast that reconciliation with Jews and the conversion demanded of married Anglican priests. In a three-step process, they must give up their heretical religion, request admission to the true faith, and then be ordained again, since popes had declared that Anglican sacraments are invalid. This does not bring Christians together, but declares more pointedly the incompatibility of Catholics and Protestants. It encourages schism in the Church of England, since the Anglicans seeking admission to the Catholic Church were opposed to the ordination of women in the 1970s and to the subsequent appointment of women and gays to be bishops. The distance between the two churches was further emphasized by the requirement that the converts not exercise their Catholic ministry in any place where they had served as Anglicans. This involved a break from old ties of locale, of friendships, and sometimes (for married couples with children) of schools.

Church

When it is said that Anglican priests have converted to the Catholic Church, one must ask which church they are entering. Since the 1960s, there have been two churches, one of the Second Vatican Council and one of recent popes. The pivotal dates for this divergence are 1965, when the council’s decrees were published, and 1968, when Giovanni Montini, Pope Paul VI, refused to accept his own commission’s recommendation to drop the ban on contraception. The first date triggered a great flooding of priests from the church to get married (the very development most Catholics now favor), and the second began a great noncompliance with papal teaching in the laity.

On the first development, the exodus of priests had reached 70,000 by last year. And even the priests who stayed are more liberal than the incoming former Anglicans: asked in 2002 whether papal moral teaching is too conservative, a third of America’s diocesan priests said that it is, while only 6 percent of the Anglican convert priests thought so. This is just one of many measures that put married priests at odds not only with other married Catholics but also with celibate priests. Asked if premarital sex is always sinful, a plurality of active (Mass-attending) lay Catholics (46 percent) said yes, a slight majority (53 percent) of diocesan priests said yes, but a supermajority (84 percent) of the convert priests said it is always sinful.

Advertisement

These new priests were twice as likely as diocesan priests to say condoms cannot be used to prevent AIDS (57 percent to 31 percent) or that it is always sinful to masturbate (64 percent to 30 percent). In fact, these new married priests thought other priests should remain celibate, though the unmarried priests thought marriage should be an option. Asked whether celibacy should be voluntary, not mandatory, a slight majority (52 percent) of supposedly celibate priests voted for the change, but only a third (34 percent) of the married priests agreed.

No wonder John Paul II was willing to recruit these priests who agreed with him for use against the many priests who did not obey him. And no wonder the convert priests have joined forces with one sector of the diocesan priests—those admitted after the 1980s. Though the number of men entering Catholic seminaries has decreased drastically, those who do ask for entry are naturally the ones willing to submit to all papal doctrine—placing them at odds not only with their fellow priests but with the laity they mean to serve. The older clergy and the laity are favorable to married priests, women priests, and contraception. The younger priests are not. They naturally seek admission to dioceses with conservative bishops. Since their seminaries have recruited more applicants than those with progressive bishops (though the scale is still small), conservatives boast that the way to increase “vocations” is to get stricter.

It is a system in which leaders are sought who will have little in common with their putative followers. This turns upside down the differences in attitude according to priests’ age. In 1970, a survey made by the priest-sociologist Andrew Greeley and a colleague found that 82 percent of those under thirty-five favored optional celibacy. Now the younger priests are the ones most opposed to any change.

Another way that the younger priests differ from the older is in their attitude toward homosexuality. As one would expect from the older men’s attitude toward celibacy, they are less condemning than the Vatican of gay behavior. Reputable studies estimate the number of gay priests as ranging from 15 to 50 percent, and a median estimate indicates that the percentage of gays in the priesthood is ten times that of gays in the general population. The Vatican says that the homosexual inclination, though it is morally disordered, is not a sin if one does not act on it. Anyone who thinks that this concentration of men with a gay inclination will not result in gay activity is as blind to reality as any pope. Years of study and counseling by the Catholic psychiatrist Richard Sipe led him to conclude that only 40 percent of priests, gay or straight, permanently practice celibacy.

The effect of mandatory celibacy may be less the abstention from sex than an obsession with it. The younger priests who accept the condemnation of homosexuality have been outspoken in denouncing their elders for fostering a gay subculture in some seminaries, making straight men uncomfortable there. Does the number of gay priests shock or disgust lay Catholics? Why should it, since another 2014 Pew poll shows that 85 percent of Catholics under thirty (and 70 percent of all Catholics) favor the moral acceptance of homosexuality, and 75 percent of the under-thirties (57 percent of all Catholics) favor gay marriage?

The numbers given above were polled or reported on by D. Paul Sullins, under a commission from Archbishop John Myers of Newark. Sullins is the head of a research team in the sociology department of the Catholic University of America, and he has published the findings of his study of Catholic priests, both married and unmarried, in Keeping the Vow. Himself a conservative convert from Anglicanism, his earlier research on the children of gay couples has been challenged, but his numbers about priests’ beliefs (as opposed to the conclusions he draws from them) seem credible.3 We would have known, even if he does not spell it out, that Anglicans fleeing liberal changes in their previous church were bound to be traditionalists.

Sullins is naturally proud of his fellow converts’ conservatism. He thinks this is a form of “fidelity” and observance that can stand as an example to priests who have succumbed to laxity. He and his companions are not hesitant about joining a church most of whose members disagree with them, since it is papal approval they are seeking. A number of them are previous converts from evangelical churches. They became Anglicans to find Authority. Not finding enough of it, they sought a Higher Authority and found it in Rome. These are just the men Popes John Paul and Benedict were hoping for. They were disappointed only that more did not come in. Whereas in 1981, John Paul kept the new priests from directly pastoral roles (a restriction largely skirted by traditionalist bishops who ordained the converts), Benedict created a new category, the “Ordinariate,” so converts can be used as pastors by their own nonlocal ordinary (bishop).

Advertisement

If we know the kinds of priests John Paul wanted, we can guess the kind he did not. I discovered this in the early 1980s when I went on assignment to Rome for an article about him. I talked with the acting general of the world’s Jesuits, Vincent O’Keefe, known to all as Vinnie. He was the acting general because the elected general, Pedro Arrupe, had suffered a stroke in 1981 and O’Keefe, as vicar general, was filling in for him. Father Arrupe, who was at Hiroshima when the bomb was dropped and ministered to the stricken there, was a liberal much loved by the Jesuits. When I asked Father O’Keefe for his assessment of the pope, he recounted his earliest meeting with him as the head of the Jesuits.

He told John Paul that he did not have anything like the pope’s experience, knowledge, or insight, but one thing he knew from his own experience. As the head of an order whose members were leaving the priesthood in large numbers, he knew that most of these men were still believers in the church, men whose talent and training could be of use to the faith; but Paul VI, stunned by the defections, had tried to stanch the flow by cutting off the deserters from further contact with the church, denying them the Catholic sacraments. O’Keefe begged the pope to regularize (“laicize”) such men’s Catholic standing. The pope said no with a curt reply: “They broke their vow.” End of discussion.

When, shortly after this, Arrupe formally resigned and the Jesuits were scheduled to convene and elect his successor, it was clear that O’Keefe, the man Arrupe had favored, and a man popular with other Jesuits, would be elected. This was a prospect so unwelcome to the pope that for the first time in the history of the order he suspended the normal election process and appointed his own conservative Jesuit as an interim general—Paolo Dezza, who had taught John Paul at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. Some Jesuits feared that the pope suspected that Jesuits would disobey him, giving him a reason to suppress the order. But O’Keefe and others urged compliance with the pope, so the right to elect their own leader was restored in 1983.

John Paul was obviously unhappy with the Jesuits, and he showered favors on newer and more conservative devotional bodies to displace their influence—Opus Dei, the Legionaries of Christ, Focolare, Communication and Liberation (supportive of Silvio Berlusconi). He was close to the child molester Marcial Maciel, who founded the Legion of Christ. It may be wondered why John Paul, who did not like Jesuits, raised the Argentine Jesuit Jorge Bergoglio—now Pope Francis—to be a bishop, then archbishop, then cardinal; but Bergoglio was at the time on the outs with his fellow Jesuits of Latin America, who thought he had opposed the liberation theology encouraged by Arrupe. This was all to the good in John Paul’s eyes.4

John Paul’s reining in of the Jesuits and promotion of traditionalists explain his strategy in the promotion of Anglican dissidents. He wanted what Father Sullins says the convert priests are supplying—a standing rebuke to other priests who are less doctrinally loyal. Pope Benedict followed this attitude toward the Anglican recruits, and he even tried to woo back the followers of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, who protested the reforms of Vatican II by launching the schismatic Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX). Benedict lifted the excommunications of four SSPX bishops, including one (Richard Williamson) who is a Holocaust denier. The pope partially revived the trademark of the Lefebvrists, the Tridentine (Latin) Mass.

Over time, under the pressure of reality, the rules governing those who give up the priesthood have been relaxed, supported by the priests who did not leave. But a similarly tolerant attitude toward excommunicating people has been in evidence in the treatment of divorced and remarried Catholics, who are customarily denied the sacraments. This was a point of contention in the recent synod of bishops, and will come up again in this year’s synod. The punitive use of sacraments is dear to the Anglican converts who have renounced their original church’s sacraments to embrace and enhance those of their new church. They feel that the way to spread belief in Jesus is to bar the approaches to Him. That is why some bishops have tried to refuse communion to Catholic politicians who do not follow papal instruction on abortion.

These bishops remind me of the Pharisees, who said people should not meet with Jesus because he eats with sinners. When this was repeated to Jesus, he said, “The healthy do not need a doctor, only the sick do. I have not come to call the virtuous but to call sinners to a change of life [eis metanoian].” This was what Pope Francis was referring to when he wrote, in his first major statement, The Joy of the Gospel: “The Eucharist, though it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

The Catholic Church, whose charm was once its serenity of certitude, had latterly become a house of many fears. That is what happens to popes who lose touch not only with their people but with their priests. Panicking over this situation, they grasp at any support they can find. Paul VI, bewildered by the council that Pope John had bequeathed him, felt he would lose all his power if prior condemnation of the Jews and of contraception no longer prevailed. John Paul II, in many ways an athletic figure who radiated strength, was afraid of Vinnie O’Keefe, and so worried about his church’s stability that he tried to prop it up with a rotten pillar like Marcial Maciel, and to bring in stealth squads of Anglicans fleeing from women wearing the chasuble. Benedict placed his hope in a rotten pillar like Lefebvre. Dealing with proof that bishops had protected child molesters, Benedict did not know what to do with the evidence. These were frightened men, moving in incense clouds of fear.

How it clears the air to have, at last, a pope who is unafraid.

-

1

Pope Francis allowed married men from Eastern Rites to be ordained in the West on June 14, 2014. See Laura Ieraci, “Vatican Lifts Ban on Married Priests for Eastern Catholics in Diaspora,” National Catholic Reporter, November 17, 2014. ↩

-

2

See John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965 (Harvard University Press, 2012), p. 180, and my review in these pages, March 21, 2013. ↩

-

3

On Sullins and gay parents, see Emma Green, “Using ‘Pseudoscience’ to Undermine Same-Sex Parents,” The Atlantic, February 19, 2015. ↩

-

4

See Paul Vallely, Pope Francis: Untying the Knots (Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 55–61, 125: Elisabetta Piqué, Pope Francis: Life and Revolution (Loyola Press, 2014), pp. 92–93; and Austen Ivereigh, The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope (Henry Holt, 2014), pp. 166–167, 202–209. Before his election as pope, Bergoglio had arranged to retire to a non-Jesuit home and be buried in a non-Jesuit cemetery. ↩