The classical music world has been saturated lately with stories about the impending demise of the orchestra and the repertory it plays. Dwindling audiences and rising costs have forced American orchestras to cut personnel, shorten concert seasons, and even cross over to the “dark side” and play popular works unthinkable a decade or two ago (as I write I see that the Louisville Orchestra is scheduled to present a program of music by Led Zeppelin in November). When the Philadelphia Orchestra, the finely tuned instrument of Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy, is forced to file for bankruptcy, has the time come to declare Beethoven dead and buried and consign his symphonies to eternal rest?

A tale related recently by the critic Norman Lebrecht suggests that it has not. Several years ago, Lebrecht reports, the BBC decided to make the complete Beethoven symphonies available to its listeners as free downloads for a week.1 At the launch, expectations were not high, since by all accounts interest in the works had greatly declined. In addition, the performing group was the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Gianandrea Noseda—respectable musicians, to be sure, but not a star ensemble such as Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. The project was given only moderate priority, and the producers anticipated several thousand downloads.

However, much to everyone’s astonishment, when the totals were counted at the end of the week they came to 1.4 million downloads of the symphonies. Forty percent of the listeners were from the United Kingdom and the United States—predictable BBC audiences. But the remaining 60 percent came from other countries, including Vietnam, Thailand, and Taiwan. Equally surprising was the fact that almost twice as many listeners chose Beethoven’s First and Second Symphonies over the Third Symphony, the mighty and popular “Eroica,” suggesting that the participants were new to the repertory altogether.

Thus there may be an audience, after all, for the nine Beethoven symphonies, and appearing just in time to enlighten it is Lewis Lockwood’s absorbing new study of the works, which makes the case that this music is about a lot more than the notes on the page. The author of the distinguished biography Beethoven: The Music and the Life (a 2003 Pulitzer Prize finalist) and Beethoven’s “Eroica” Sketchbook: A Critical Edition (2013, with Alan Gosman), Lockwood has been involved with Beethoven research for more than forty years, carrying out his work first at Princeton and then, from 1980 onward, at Harvard, where he is Fanny Peabody Professor of Music Emeritus. He is one of the last stalwart defenders of source studies—the evaluation of the music through the examination of the composer’s original manuscripts. That approach yields remarkable insights in his new book.

There is no shortage of writings on the Beethoven symphonies. The list begins with Hector Berlioz’s collected essays from the 1860s and continues with George Grove’s classic study of 1884 and the lesser accounts of Jacques-Gabriel Prod’homme (1906), Karl Nef (1928), and Antony Hopkins (1981). Such respected writers as Ralph Vaughan Williams, Donald Francis Tovey, and Maynard Solomon have discussed the Ninth, and the great Austrian theorist Heinrich Schenker has contributed dense analyses of the Third, Fifth, and Ninth. From these and other studies, the broad outline of Beethoven’s compositional approach to the symphony is well known.

Beethoven delayed writing a symphony until 1799–1800, when he was thirty years old and firmly established in Viennese circles as the successful composer of piano and chamber works. His first two symphonies, No. 1 in C Major, finished in 1800 and published as Opus 21 in 1801, and No. 2 in D Major, completed in 1802, were solid pieces in the traditional Viennese mold (though Lockwood makes a case for subtle innovations in No. 2). At that point Beethoven went through a severe personal crisis as he realized that his loss of hearing, first sensed around 1796 when he was twenty-five, was irreversible and would probably get worse. In an anguished letter to his brothers, the famous Heiligenstadt Testament of 1802 (named after the town outside Vienna where he was staying), he lamented his fate and admitted that he had considered ending his life. But art held him back, he wrote, making it impossible for him to leave the world until he had brought forth all that he felt within himself. The letter remained unsent and was discovered after his death.

The result of this self-reflection and resolve was Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major of 1804, in which Beethoven broke with classical tradition and created a work of unprecedented scale and complexity. Called “Eroica” (Heroic) and dedicated “To the Memory of a Great Man” (originally Napoleon, until he crowned himself emperor and fell from Beethoven’s favor), the work liberated the symphony from eighteenth-century conventions and drew listeners into an emotional realm of struggle, endurance, and triumph. From then onward Beethoven produced a series of highly individualistic symphonies, normally writing two together, one radical, one conservative. The tame Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major provided a balance to the “Eroica” in 1806. Then, in 1808, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor complemented Symphony No. 6 in F Major (“Pastoral”). In 1812, Symphony No. 7 in A Major appeared with Symphony No. 8 in F Major. Finally, after a hiatus of ten years and his descent into total deafness, came the monumental Symphony No. 9 in D Minor in 1824, the most radical of them all and the first symphonic work to incorporate solo voices and chorus.

Advertisement

Along the way Beethoven introduced a steady series of innovations, including disorienting syncopation and wrenching dissonance. (“Beethoven always sounds to me like the upsetting of bags of nails, with here and there an also dropped hammer,” John Ruskin remarked.) He also used a cyclical format with recurring motifs unifying the entire work (the ubiquitous short-short-short-long rhythmic idea in the Fifth Symphony, for example). And he expanded the scherzo from three-part to five-part, transformed the coda into a second development section, and introduced a new multiplicity of themes in expositions and development sections.

If all this is apparent from past accounts, do we need another survey of the symphonies? Lockwood answers yes, because of the large amount of new research carried out in the last fifty years and the availability of sketch material that has remained undeciphered until recently. It is Lockwood’s great gift to be able to assimilate the extensive literature and research on the symphonies and draw on it to write a clear, highly readable, up-to-date account, acknowledging past commentators while bringing to bear the observations of recent scholars and the mostly familiar remarks of Beethoven and his contemporaries.

Lockwood begins with an introduction on Beethoven’s view of the symphony (“the triumph of this art”) before devoting a chapter to each symphony, discussing specialized topics pertinent to the work in question. For the Sixth Symphony, for instance, his topics include “Beethoven and Nature,” “Depiction and Representation,” and “The ‘Pastoral’ Symphony as a Unified Artwork.” He concludes with an epilogue describing the impact of Beethoven’s symphonies on two very different events: the founding of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the 1880s and an orchestra performance by the inmates of the Łódź ghetto in Poland under the Nazi occupation in the early 1940s.

Two themes dominate Lockwood’s survey: Beethoven’s desire to move audiences emotionally with his symphonies and the importance of the composer’s sketch materials for understanding the works.

The rapid growth of public concerts in the second half of the eighteenth century brought with it a middle-class audience that felt entitled to express its pleasure or displeasure with the music it heard. Unlike audiences today, these early listeners not only appeared to understand the conventions of the works they were hearing but also responded actively to specific musical gestures. Witness Mozart’s report to his father of the audience reaction to his Symphony in D Major (“Paris”), K. 300a, in 1778:

I prayed to God that it might go well, for it is all to His greater honor and glory; and behold, the symphony began…. Just in the middle of the first Allegro there was a passage which I felt sure must please. The audience was quite carried away—and there was a tremendous burst of applause. But as I knew, when I wrote it, what effect it would surely produce, I had introduced the passage again at the close—when there were shouts of “Da capo!”

The Andante also found favor, but particularly the last Allegro, because, having observed that all last as well as first Allegros begin here with all the instruments playing together and generally in unison, I began mine with two violins only, piano for the first eight bars—followed instantly by a forte. The audience, as I expected, said “hush” at the soft beginning, and when they heard the forte, they began at once to clap their hands. I was so happy that as soon as the symphony was over, I went off to the Palais Royal, where I had a large ice and said the Rosary, as I had vowed to do.2

By today’s standards, this was a very active audience response. But it was also an ephemeral response, and one suspects that the participants went out afterward and had a large ice, too.

Beethoven wanted something else. He sought to move the audience’s soul, not just please it with musical effects. He wanted the symphony to become a cathartic listening experience and a force for change. Lockwood suggests that Beethoven’s expanded vision of the symphony as an emotional agent evolved over several years, emerging with the hearing crisis of 1802 and bursting forth in full force in the “Eroica” of 1804. He believes that this symphonic aesthetic may have originated in Beethoven’s exposure to the plays of Friedrich Schiller as a boy in Bonn, and he cites a description of Schiller’s early work The Robbers at its premiere in Mannheim in 1782:

Advertisement

The theater was like a madhouse—rolling eyes, clenched fists, hoarse cries in the auditorium. Strangers fell sobbing into one another’s arms, women on the point of fainting staggered towards the exit. There was a universal commotion as in chaos, out of which a new creation bursts forth.

The Robbers played in Bonn later that year, and while there is no record that the twelve-year-old Beethoven was in attendance, there is good evidence that he had some acquaintance with Schiller’s works when he was young. As an adult he knew many passages of the plays by heart and quoted them in letters and conversation. Lockwood stresses that it was the ability, inspired by Schiller, to stir large audiences to emotional depths they had not experienced before that Beethoven desired in his symphonies and that separates them from the works of Haydn and Mozart, which were aimed more toward entertainment than edification.

Beethoven toyed with the idea of setting Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” as early as 1793 and returned to it several times before finally using it in the finale of the Ninth Symphony, almost thirty years later. The “Eroica,” with its heroic themes, harmonic and rhythmic conflicts, pathos-filled funeral march, and other dramatic elements, was the turning point, the moment when Beethoven moved from Mozart to Schiller as his model. In the Fifth Symphony Beethoven presented an abstract but palpable journey from trial (“fate knocking at the door”) to triumph, and in the Ninth Symphony he went farther still, expressing a utopian vision of universal brotherhood through Schiller’s ode.

For audiences, hearing the Ninth in 1824 was a very different experience from hearing Mozart’s “Paris” Symphony in 1778. A review of the Ninth’s premiere commented:

The effect was indescribably great and magnificent, the jubilant applause from full hearts was enthusiastically given the lofty master, whose inexhaustible genius revealed a new world to us and unveiled never-heard, never-imagined magical secrets of the holy art.3

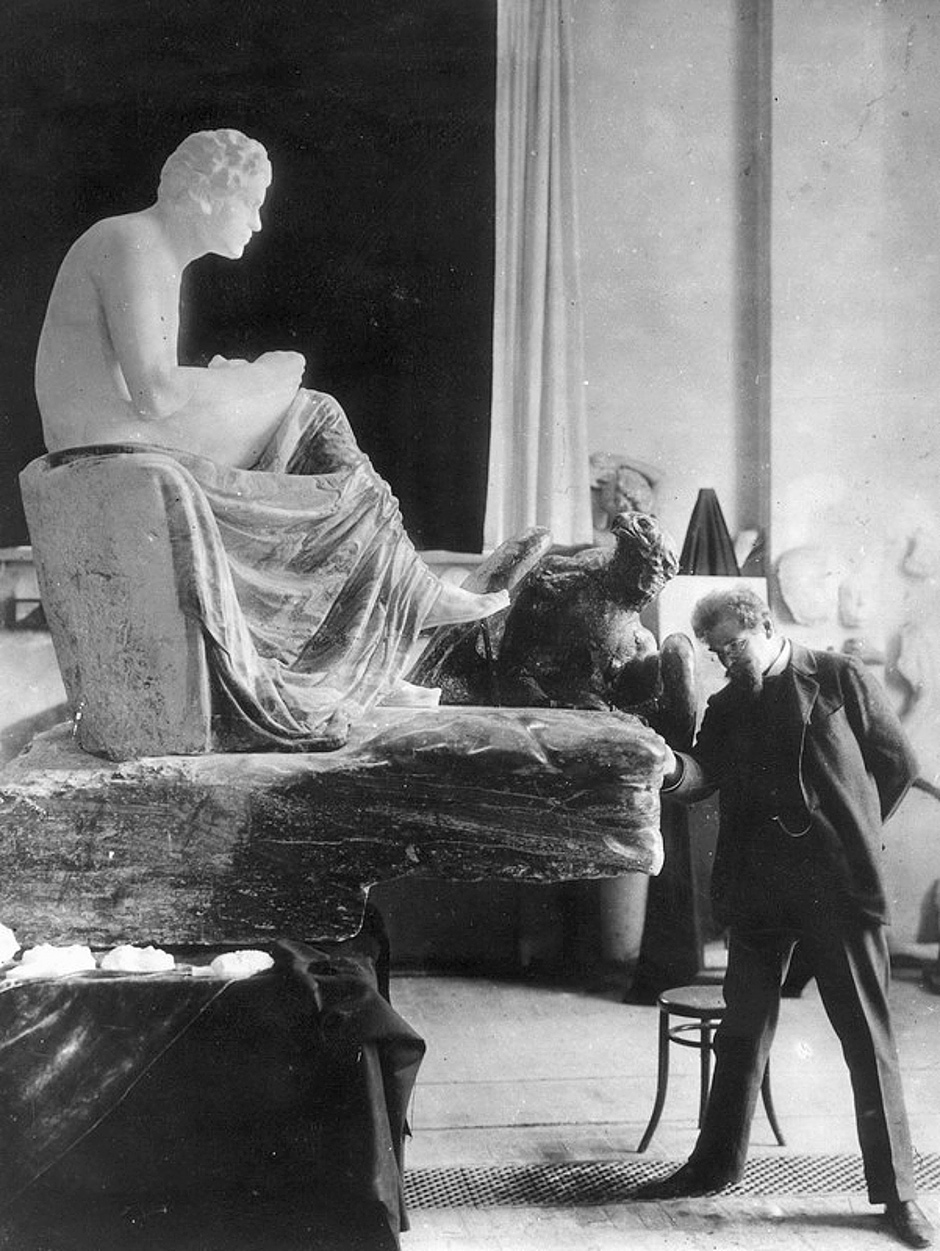

In Beethoven’s hands, the symphony had become a source of quasi-religious revelation—a “holy art.” It is no surprise that Max Klinger’s statue for the 1902 Beethoven Exhibition in Vienna featured the composer sitting mostly naked on a throne, like a Greek god.

Lockwood’s second premise, the importance of Beethoven’s sketches for understanding the symphonies, is even more central to the book. When composing, Beethoven relied on an extensive sketching process, using both large drafting albums in his study and smaller pocket sketchbooks on his daily walks. Many of these manuscripts survive, and they show that Beethoven worked on several projects simultaneously, and that most of his compositions underwent a long genesis, sometimes stretching over a period of years. Themes, passages, and movements were drafted and revised many times over, until Beethoven was satisfied that the final version achieved the precise effect he desired. The sketchbooks also contain a running commentary on the material, as the composer pondered to himself the music he was working on as well as ideas for pieces in the future.

The first hint of the “Pastoral” Symphony, for instance, occurred four years before its completion, in an idea for a “lustige Sinfonia” (joyous symphony) that appears directly after Beethoven’s first sketches for a work in C minor that turned out to be the Fifth Symphony. The sketchbooks provide entry into Beethoven’s private world, showing not only how he composed the symphonies and other pieces but also his intentions and hopes as he crafted and shaped the musical materials.

The importance of the sketchbooks was first demonstrated by the German musicologist and composer Gustav Nottebohm in a series of essays published in the 1870s and 1880s, and his findings were used by Grove a decade later in his survey of the symphonies. But whereas the sketch materials were peripheral to Grove’s discussion, they are central for Lockwood, who uses them time and time again to trace the compositional background of the works and the development of important concepts. He even draws them into the descriptions of the music itself, pointing out that the last movement of the First Symphony begins “like a miniature sketch-process that builds up the first theme one fragment at a time” and that the mystical opening of the Ninth Symphony is “like the process of composition itself, from premonition to embodiment.” This method of interpreting the works by evoking the composer’s compositional process is Lockwood’s most notable contribution to the literature on the symphonies.

The main conclusion that he draws, working from the sketch material, is that Beethoven was absorbed with symphonic composition throughout his life, not only completing the nine known pieces but sketching or considering ideas for almost two dozen other works. Most of these remained undeveloped, but taken together they demonstrate, in Lockwood’s view, Beethoven’s imagination “returning to the idea of the symphony across the span of his career, from early to late.” This is the artistic vision in the book’s title: an ongoing preoccupation with the symphony as the pinnacle of Western music, the means through which a composer expresses his greatest thoughts to the largest possible audience. In an appendix Lockwood presents a “provisional list” of the known symphonic sketches in chronological order. Nothing could make clearer the case for Beethoven’s constant return to the symphony.

Other fascinating deductions from the sketches include the following:

At an early point Beethoven considered a slow introduction for the opening of the “Eroica” Symphony but dropped it, possibly because it would have detracted from the second movement, the funeral march, which commemorates death in a symphony for the first time. It was the second movement, even more than the first, that moved the symphonic experience into the Romantic era.

In the case of the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven sketched movements 1 and 3 several years before turning to movements 2 and 4. He initially considered a traditional last movement in C minor before coming up with the idea of switching the mode from minor to major to produce the triumphant C-major finish. It is surprising that this central concept, seemingly the raison d’être of the work, occurred long after composition was underway.

The idea of a choral finale was a fundamental premise of the Ninth Symphony from the start, but Beethoven struggled with the problem of how to introduce the voices and how to set Schiller’s ode. Beethoven was determined to convey the poem’s message of universal brotherhood by creating a “people’s hymn,” a tune that would be attractive and rich in motifs but also easy to sing—a national anthem of sorts taken to a higher level for a worldwide community. The sketch material shows that the “simple” melody, consisting of four-bar phrases, stepwise motion, and a one-octave range, was not easily achieved: Beethoven sketched almost twenty variations of the spontaneous-sounding tune before he was fully satisfied.

When composing the Ninth Symphony, Beethoven briefly considered a companion work, a symphony in “ancient modes.” It was to feature a “Cantique Ecclesiastique,” and the orchestral violins were to be increased tenfold in the last movement. (This begins to sounds very much like Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, the so-called “Symphony of a Thousand” of 1906–1907, which uses the ancient Latin hymn Veni creator spiritus and calls for the addition of an antiphonal brass choir in the finale.) This symphony was never carried forth, though Beethoven did sketch ideas for another work, the so-called Tenth Symphony (completed in the 1980s, amid controversy, by Barry Cooper).

If Lockwood’s survey has a drawback, it is the varied approach to analyzing each symphony. In some cases, he walks the reader through the work by using a nontechnical prose description, almost in the manner of nineteenth-century writers. In other instances, he presents structural charts accompanied by analytical commentary and music examples (mostly on a related website) that would hardly be understood by a general reader. At still other places, he turns to the sketch material as a basis for explaining what’s happening musically.

Lockwood informs the reader in his introduction that he will treat the individual symphonies in different ways, but this occasionally leads to an inconsistency that can be frustrating. For instance, he presents helpful layout charts for the first eight symphonies (indicating the tempo, meter, and key of each movement), and he occasionally gives a detailed analytical outline of particular movements, such as the slow movement, “Scene by the Brook,” of the “Pastoral” Symphony. But for the Ninth Symphony, Beethoven’s largest and most complex piece, he gives neither. After reading the spirited discussion of the evolution of the “Ode to Joy” melody, I turned the page quickly, eager to see how Lockwood analyzed the famous finale, which from a formal standpoint can be viewed in a number of ways. What I found instead was the epilogue to the entire book.

It is ironic that Lockwood’s survey demonstrating the great usefulness of source studies appears at a time when the future of such research seems in doubt. The origin of his work with the sketchbooks can be traced to the great outburst of American and British scholarship that accompanied the Beethoven centennial and sesquicentennial in the 1970s. One heard Beethoven’s music at special festivals and celebrations almost every week during those years, and, through detailed analysis of the sketches and composition scores, Lockwood, Joseph Kerman at Berkeley, and Alan Tyson at Oxford led the quest to know just how the pieces were created. This work continued in the 1980s, but the initial enthusiasm has faded as musicology has turned to gender studies, reception history, and other specialties that focus more on psychological, sociological, and political matters than the music itself.

Lockwood limits mention of this scholarship to footnotes, for the most part, perhaps because it detracts from his fundamentally nineteenth-century view of Beethoven as a heroic figure presenting an ethical vision in his symphonies (Klinger’s enthroned Beethoven). He touches just once on the work of Michael Broyles, who described Beethoven’s intrusive use of C-sharp in the F-major finale of the Eighth Symphony as a comedy bordering on rage: “It is,” Broyles is quoted saying, “rough, it is crude, it is calculating of the lowest sort.” And Lockwood consigns the contributions of the feminist musicologist Susan McClary to a single mention at the back of the book. At several points he refers to the source work that remains to be done, pointing out that 80 percent of the symphonic sketch material still awaits transcription. Alas, “musicology in the twentieth century moved in other directions,” he writes.

Whether anyone will continue the work of Lockwood and others on Beethoven’s sources remains to be seen. Lockwood praises Erica Buurman’s recent studies at the University of Manchester of Beethoven’s concept sketches for multimovement compositions, and he mentions a few others, but the energy behind source investigation has mostly dissipated. Is Lockwood’s volume a valedictory for this type of research? In Bach scholarship, the ambitious Bach Digital project of the University of Leipzig has made the autograph sources of Bach’s music available to all online, at no cost, for scrutiny and appraisal. Unfortunately there is no similar attempt in Beethoven scholarship to provide universal access to the composer’s manuscripts, sketches, and conversation books. Such availability would fit well with Beethoven’s idealized view of universal cooperation and forward progress.

Meanwhile, Lewis Lockwood has served as an admirably articulate guide to the symphonies, drawing on a lifetime of scholarly investigation to explain the music, methods, and artistic vision of the composer. Like the BBC downloads, his book will surely inspire new interest in Beethoven’s durable masterpieces.

-

1

Norman Lebrecht, The Life and Death of Classical Music (Anchor, 2007), pp. 139–140. ↩

-

2

Adapted from The Letters of Mozart and His Family, edited by Emily Anderson (Norton, 1985; third edition), p. 558. ↩

-

3

See Thomas Forrest Kelly, First Nights: Five Musical Premieres (Yale University Press, 2000), p. 175. ↩