Great cities have often been compared to whores. The Whore of Babylon, mentioned in the Book of Revelation, may have been a metaphor for imperial Rome, or possibly Jerusalem. Juvenal’s satirical poem about Rome, written at the end of the first century AD, conjures up the lascivious image of Messalina, Emperor Claudius’s wife, as a symbol of urban depravity. At night, the “whore-empress” made straight for the brothel, “with its stale, warm coverlets,” where “naked, with gilded nipples, she plied her trade….”1

The city, in Juvenal’s time as much as our own, was a place where everything, including sex, was traded, where the constant flow of money broke the barriers of race or tribe. The illusion of cultural purity cannot survive in the urban melting pot, hence the ancient strain of native distrust of foreigners. Juvenal’s satire of Rome is filled with two-faced Greeks and grasping Jews, deceitfulness and greed being the twin vices commonly associated with city life.

In 1874, Gustave Moreau did a painting of Messalina, nude except for her rich jewels, groped by a young Tiber fisherman, while a couple of exhausted debauchees lie prone at the feet of a procuress. Like Juvenal, whose poem he knew well, Moreau drew a moral from this scene of what he called “debauchery leading to death.” Except that in this case it wasn’t Rome that stood for terminal decadence, but Paris under Napoleon III’s Second Empire, which had come to an ignominious end four years before.

So the prostitute as an artistic icon is not new. But rarely has she been as obsessively depicted and described, in painting, print, or sculpture, in novels, popular songs, and photographs, as in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century France. As idealized figures of fashion, the courtesans and prostitutes in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Japanese woodblock prints and fiction also come to mind. They were almost never as realistically portrayed as in late-nineteenth-century French art, but at least one reason for their prominence was similar to what created the later vogue for cocottes, filles de maisons, or horizontales in France: the shift from aristocratic or feudal customs to the dictates of the marketplace. Prostitution, in its many manifestations, grew exponentially with the rise of the modern city.

The exhibition “Splendours and Miseries: Images of Prostitution in France, 1850–1910” at the Musée d’Orsay is exhaustive—in fact, a little bit too exhaustive; after viewing a dozen pornographic photographs reenacting brothel scenes, you get the point. You don’t need dozens more. The same is true of prints by Felicien Rops, an interesting but minor artist, best viewed in smaller doses. Perhaps because the former Orsay railway station is so vast, shows designed to fill its space have a tendency toward overkill, and run the risk of incoherence.

Still, the exhibition, organized together with the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, is full of wonders, and has a far more serious purpose than some French critics have acknowledged.2 It is fascinating to see, for example, how the image of prostitutes changed, not just from artist to artist, but in the course of time. The show is not just about art, but an absorbing illustration of social history.

There is of course no fixed definition of the prostitute. Paid sex ranges from Empress Messalina’s amateur pursuits to the grand Parisian courtesans who sometimes made fortunes by consorting with bankers and monarchs. Were the ballet dancers in Jean Béraud’s painting Backstage at the Opéra (1889) prostitutes? We see them being fondled and whispered to by elderly gentlemen, who seem to have no other business hanging around backstage. Underpaid, and sometimes no doubt socially ambitious, many of these dancers were available for a price.

Was the girl returning the gaze of a well-dressed gentleman staring through the window of her lingerie shop in James Tissot’s splendid The Shop Girl (1883–1885) a whore? Not strictly speaking, probably. But like ballet dancers and actresses, shop girls were part of a vast army of poor young people who flocked to the big city, where they made do as best they could, often by selling sexual favors. It was indeed the very ambiguity of women and girls prowling the boulevards, serving in brasseries, delivering linen, dancing at the Opéra or in less reputable dance halls that lent drama to much French painting in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Isolde Pludermacher, one of the show’s curators, explained her aim to Le Figaro. She wished “to restore for today’s viewers the keys to reading pictures that were more or less explicitly related to prostitution at the time.”3

But even if one can read the signs—the saucy look, the unusually heavy makeup, the small pet dog yapping at an exposed ankle under a slightly lifted skirt—a degree of ambiguity often remains. During the Second Empire, lasting from 1852 to 1870, paid sex flourished largely behind the doors of brothels called maisons closes. As Richard Thomson points out in his catalog essay, “a system intended to be invisible remained so.” Very few artists, unlike in later periods, penetrated those doors, certainly not with the intention of drawing pictures. An exception was Constantin Guys, the artist Baudelaire championed as “the painter of modern life,” who did some interesting drawings in ink and watercolors of brothel scenes in the 1850s, some of them cheap dives with sailors and soldiers, some of them catering to a richer clientele.

Advertisement

There was, however, a pronounced taste for the opulent glamour of celebrated courtesans, painted, sometimes in the nude, as simpering Greek goddesses, nymphs, or in several renderings as Mary Magdalene, sometimes penitent, as in Paul Baudry’s 1858 picture, sometimes less so. An oil painting done by Alexis-Joseph Perignon in 1866 shows a young woman dressed as a Renaissance aristocrat. She was actually a soprano named Hortense Schneider, playing the part of one of Bluebeard’s wives. When not on stage, Schneider was the mistress of many rich men, including Edward, Prince of Wales (whose antics in Parisian brothels can be guessed at by the display at the exhibition of an elaborate love seat with bronze stirrups). Schneider’s success as a courtesan was such that she was known as the Passage des Princes.

In any case, in art as often in life, Second Empire prostitution was glossed over or elaborately disguised. One way of showing illicit erotica was to place it in the exotic realm of cultural or historical allegory. Jean-Léon Gérôme’s pictures of Oriental harem ladies lounging around communal baths are well known. In this show, we see a famous Greek courtesan posing naked in front of her lecherous judges (Phryne Before the Areopagus, 1861), or the even cheesier Greek Interior (1850) with dreamy nudes posing languidly on lionskin rugs and plump cushions. Gérôme was a member of the “Neo-Grec” circle of artists who worshiped all things Greek, which in his skillful hands had a tendency to turn into soft porn.

One of the greatest and most famous paintings in the Orsay exhibition is Édouard Manet’s Olympia of 1863. The picture came as a shock to contemporary critics for a reason that might now be obscure. As with many contemporary paintings of high-end courtesans, Manet shows a beautiful young woman in the nude, with embroidered silk slippers, a gold bracelet, and an elegant black choker around her neck. However, unlike Gérôme’s airbushed harem girls or Baudry’s slick goddesses, Olympia is a woman of flesh and blood gazing at us rather impudently from her casually made-up bed, being offered a bunch of flowers (from a recently departed lover perhaps) by her black maid, and a cat (chatte is pussy in French) at her feet. Olympia oozes sex. This prompted people at the time to see her as a vulgar slut. Upper-class sex, after all, could only be depicted through a gilded haze of myth. That is why Isolde Pludermacher associates Manet’s masterpiece with the invention of the modern nude. One sees what she means, even though one might say that in terms of realism, Rembrandt and Titian, or indeed Velázquez, had already prepared the way.

Around the time that Manet painted Olympia, Paris was being transformed from a medieval warren of often dirt-poor neighborhoods into a modern metropolis with wide, brightly lit boulevards, large squares, fine parks, and the straight rows of uniform gray apartment buildings we now associate with the city. This was undertaken partly as a political measure to make it harder for rebels and revolutionaries to lurk in urban shadows. But Napoleon III was also a great modernizer. Nineteenth-century notions of hygiene played a part. The emperor wanted to “let the sun’s vertical rays penetrate everywhere…like the light of truth in our hearts.” So the prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann was commissioned to make over Paris, a grand projet he ruthlessly carried out. Artists, writers, poets, pamphleteers, singers, and filmmakers have been waxing nostalgic over the Paris that was lost ever since.

In his superb new book, The Other Paris, Luc Sante compared Haussmann to twentieth-century political megalomaniacs responsible for such monstrosities as the Bastille Opera and the Arch of La Défense.4 Sante, too, deplores the way street life has been sucked out of the urban fabric by the destruction of the old, the marginal, the poor, and the free. He has every reason to.

And yet, if one looks at prostitution, the story is not so straightforward. For it was the same forces of modern life—the expansion of the city, the migration of mostly poor people from the provinces, the spread of the bourgeoisie, the demands of republican egalitarianism—that brought prostitutes, as well as other marginal entertainers and assorted grifters and crooks, out into the open, into the new streets and boulevards, the brasseries and dance halls. More and more women called insoumises (free, rebellious) rejected the strictures of organized brothels and went out to find clients by themselves. Fairly swiftly, the romantic fascination for celebrated courtesans made way for a new realism, a fresh artistic gaze at the miseries of paid sex, as well as the often sordid glamour of its representation. Haussmann’s Paris had a sexual street theater, full of ambiguity, all of its own, embodied by the crowd, where men and women of all classes mingled, often to disreputable ends.

Advertisement

The Third Republic, founded in 1870, was marked by reformist zeal as well as a great deal of moralism, the two frequently coming together. Authorities tried to crack down, without much success, on unregistered prostitution. Street girls were not allowed to attract attention by wearing flashy clothes that gave away their line of work. Prostitutes (or women suspected as such) were regularly picked up and forced to go through humiliating medical inspections. And moralists also tried to crack down on pictures that showed the sexual trade in an honest way.

In 1877, the Salon rejected Manet’s wonderful portrait of Nana, a high-class cocotte.5 There she is, in her silk underwear, powdering her face, her lacy behind facing an appreciative male sitting on a sofa, fully dressed in top hat and evening clothes, a phallic cane jutting from his lap. What everyone knew, of course, is that men—upper-class, bourgeois, and from the lower classes too—frequented prostitutes all the time. One might even say that prostitution was an especially important institution in a morally repressive society. Strict family men were offered a way to let off steam. This was true of eighteenth-century Japan, Victorian London, and nineteenth-century Paris. It produced a degree of hypocrisy that artists loved to undermine.

Stripping away the artificial façade, debunking myths and fantasies, is one of the marks of disenchanted modern art. There are many ways of doing this, one of which is the documentary approach. Jean Béraud’s painting Waiting (circa 1885) is an interesting example. We see a smartly dressed insoumise standing on the corner of an empty Parisian street (rue Chateaubriand), one dainty boot touching the gutter, looking tentatively toward a black-suited man hovering under a street light. A second painting, showing exactly the same spot, also made around 1885, The Assignation in the Rue Chateaubriand, shows us another young woman with downcast eyes and a faint smile, being propositioned by a typical bourgeois male figure in a smart top hat, looking a trifle anxious to settle the deal.

There is something deliberately anti-romantic about these paintings. The imminent or actual transaction is straightforward, businesslike. One doesn’t have to be a learned reader of nineteenth-century visual signs to know what is going on. The human encounter is stark, just two people in an empty street. There is nothing especially erotic, let alone salacious. Only the gutter between the woman and her john suggests a squalid side to the meeting.

Another painting by the same artist, The Boulevard Montmartre, at Night, in Front of the Theatre de Variétés (circa 1882), reveals a more crowded form of street theater: a young woman on a busy sidewalk glances over her shoulder at a man in a brown overcoat, who looks as if he might be about to follow her, to a nearby hotel perhaps. Another young woman, with her back to us, is conducting some kind of business with a waiter. Wineglasses stand empty on two café tables. The illuminations of the Variety Theater in the background light up the scene.

The looming presence of a theater in the painting is, I think, a clear sign. For prostitution is a form of drama, of performance, even of suspended disbelief. When Zola’s Nana puts on her make-up in front of her slavish admirer, Count Muffat, he is “bewitched by the perversion of the powders and the pigments, seized with an inordinate desire for that painted beauty….”

What people buy is not just a person’s body, but a fantasy of romance. Brothels were often highly theatrical enterprises. The one favored by the Prince of Wales, Le Chabanais, near the Palais-Royal, is well described in Luc Sante’s book. It had rooms in the style of Louis XV, medieval torture chambers, Japanese and Moorish rooms, and even something modeled after a villa in Pompeii. Other establishments offered moving railway carriages, pirate ships, and so on.

In many cases, as I’ve said, the theater itself, featuring pretty young actresses and ballet dancers, was not so far removed from the brothel. (As a matter of fact, females were banned from the Kabuki stage in seventeenth-century Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka, because so many of them doubled as prostitutes, only to make way for young male actors, who proceeded to do exactly the same thing.)

This meant that pictures of paid sex in the last decades of the nineteenth century were in their way as theatrical as the allegories and Orientalist fantasies of the early Second Empire. But with one big difference: artists like Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, or Jean-Louis Forain did nothing to disguise reality; they showed theater for what it was, a performance, sometimes a highly skillful one, at other times just sad, even pathetic.

Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec did their most interesting work behind the scenes, as it were. Lautrec not only patronized dance halls, where he observed feverish men on the prowl, wiry pimps, and sad-eyed whores, but he was especially good at showing brothel life after the performances were over: tired prostitutes playing cards in their dressing gowns (The Card Game, 1893), or women slumped in their chairs staring at nothing in a state of exhaustion (In the Salon, 1893).

Lautrec has sometimes been described as coldhearted in his portrayal of low life. He was certainly a caricaturist who didn’t flinch from the tawdriest aspects of nocturnal Paris. One contemporary critic described the style as “graveyard comical.” But satirical bite, it seems to me, is more often directed at the male clients than at the women. A recurring theme in the work of Lautrec, as well as Degas and others who worked the graveyard comical vein, was the tension between bourgeois respectability and lust. Prostitution, wrote Baudelaire, quoted in Richard Thomson’s essay, was “the perfect image of the savagery that lurks in the midst of civilization.”

A stereotypical image of brothel life, done over and over again by Degas, Lautrec, as well as others, such as Forain or Rops, is of one or more whores in the nude, or only in stockings and shoes, posing in front of seated men who are fully dressed in respectable dark suits. In a pastel drawing by Degas, dated around 1876, a naked prostitute is pulling the arm of a prissy-looking gentleman in a three-piece suit and a bowler hat, while three other naked women look on with amused expressions. The picture is called The Serious Customer.

Another drawing by Degas, this one made around 1877, shows the back of a naked woman casually combing her blond hair in front of a dressing table with the customary towel and bowl of water. The man watching her, again fully clothed, looks sated, as though he has just eaten a rich meal. In Forain’s The Customer (1878), a plump man in a black suit and silk top hat leans on his cane, scrutinizing four naked women in colorful stockings striking poses for his inspection. In an extraordinary lithograph by Edvard Munch, The Alley (1895), one pale naked woman is surrounded by rows of faceless men in black, as though she were running a gauntlet.

There is no attempt to make the women look beautiful or even especially alluring in these pictures. In drawings by Degas in particular, there is even a distinct air of disgust. This has something to do with the attempt at realism, but is also indicative of how prostitution was seen in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Paid sex was deemed a necessity, its theatricality a subject of endless fascination to artists and titillating to the bourgeoisie, but at the same time something to be feared, not least because of venereal diseases, and thus to be kept at more than arm’s length from respectable society.

This tension was caught most famously in Maupassant’s short story “Boule de Suif” (1880). There is an 1884 painting of the same name by Paul-Émile Boutigny, showing the main character of the story, a stout prostitute, nicknamed Boule de Suif, or “Butterball,” just after she has submitted to a Prussian officer, who made the tryst a condition for allowing her and a company of highly respectable men and women to leave town in a stagecoach (the story takes place just after France was humiliated in wartime defeat by the rampant Prussians). She cuts an abject figure of shame, with her fellow passengers, in dark clothes and silk hats, turning away as though afraid of contamination.

The hypocrisy of these same reputable burghers who had only hours ago virtually forced a patriotic, rather dignified, and extremely reluctant Boule de Suif to give in to the Prussian so that they might safely get away is described by Maupassant with dark humor. But the story has one brilliant detail that exposes the deeper nature of bourgeois pretenses. As they discuss ways of persuading the prostitute to have sex with the strapping officer, and all that this might entail, the upright women get rather overexcited. That night, writes Maupassant, there was little sleep in the hotel bedrooms where the couples stayed.

In the art of the early twentieth century, as though presaging extraordinary brutalities soon to come, humor often turned into outright horror, more so even than in pictures by Degas. Caricatures of prostitution became increasingly grotesque. Drawings by Rops, done in the 1880s, already explored the specter of illness and death in prostitution, as in his picture of a skeleton with the mask of a beautiful woman soliciting a male customer in a dark alley (Human Parody: Street Corner, at Four in the Morning, 1881). In paintings by Georges Rouault (Fallen Eve, 1905, for example), the naked whores look positively monstrous. A red-headed ogre in Maurice de Vlaminck’s At the Bar (1900) stares at us over a glass of what looks like dried blood.

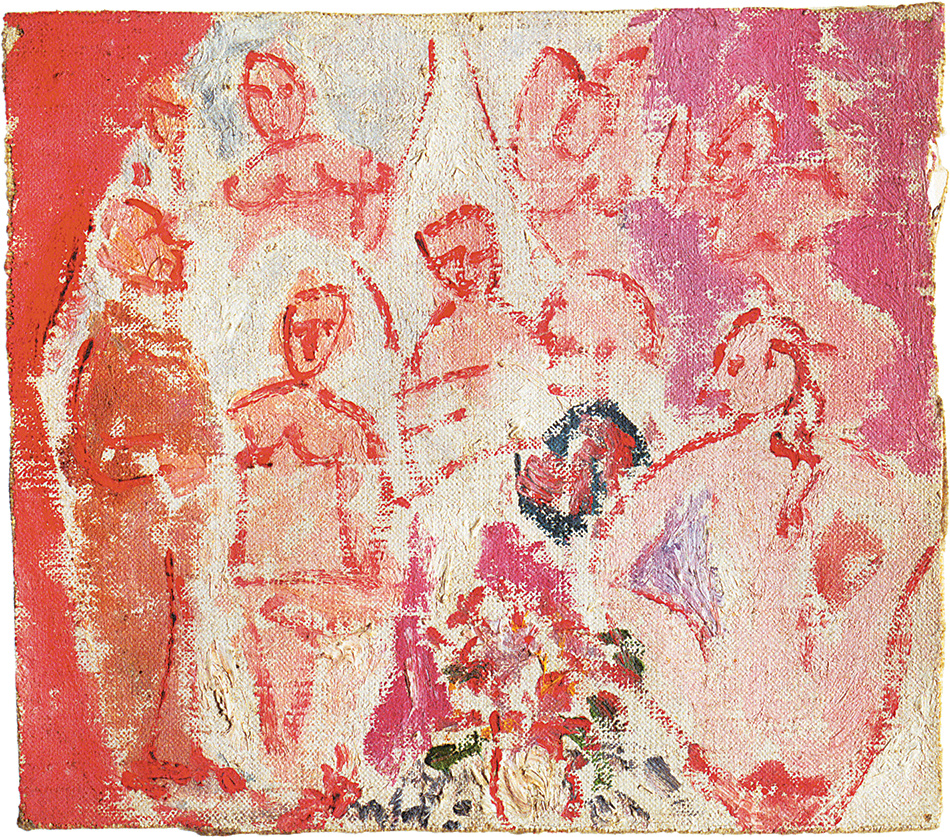

But by far the most powerful and most disturbing picture of women displaying themselves for the pleasure of men is not actually in the exhibition, but at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Musée d’Orsay has to make do with a study of the picture, which is already remarkable enough. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) shows five naked women striking strange, jagged poses, like shards of broken glass, with faces like African tribal masks. Picasso preferred to call this painting “My Brothel.” The inspiration was a street of whorehouses in Barcelona. Picasso’s masterpiece is devoid of glamour, moralizing, or documentary realism. Contemporaries, such as Matisse, were shocked by its harshness. Here is Baudelaire’s savagery lurking in the midst of civilization. But it is also an image of terrifying beauty and endless fascination, which is after all the main point of the show.

-

1

Juvenal, The Sixteen Satires, translated by Peter Green (Penguin Classics, 1999). ↩

-

2

See, for example, Harry Bellet’s attack on the show, “Les œuvres érotiques, ‘blockbusters’ des musées parisiens,” Le Monde, October 2, 2015. ↩

-

3

“Splendeurs et misères à Orsay: cinq visions de la prostitution,” Le Figaro, September 28, 2015. ↩

-

4

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015; reviewed in these pages by Robert Darnton, November 19, 2015. ↩

-

5

Nana, later the title of Émile Zola’s famous novel, published in 1880, was the slang expression for loose women. ↩