Wisconsin is probably the most beautiful of the midwestern farm states. Its often dramatic terrain, replete with unglaciated driftless areas, borders not just the Mississippi River but two great inland seas whose opposite shores are so far away they cannot be glimpsed standing at water’s edge. The world across the waves looks distant to nonexistent, and the oceanic lakes stretch and disappear into haze and sky, though one can take a ferry out of a town called Manitowoc and in four hours get to Michigan. Amid this somewhat lonely serenity, there are the mythic shipwrecks, blizzards, tornadoes, vagaries of agricultural life, industrial boom and bust, and a burgeoning prison economy; all have contributed to a local temperament of cheerful stoicism.

Nonetheless, a feeling of overlookedness and isolation can be said to persist in America’s dairyland, and the idea that no one is watching can create a sense of invisibility that leads to the secrets and labors that the unseen are prone to: deviance and corruption as well as utopian projects, untested idealism, daydreaming, provincial grandiosity, meekness, flight, far-fetched yard decor, and sexting. Al Capone famously hid out in Wisconsin, even as Robert La Follette’s Progressive Party was getting underway. Arguably, Wisconsin can boast the three greatest American creative geniuses of the twentieth century: Frank Lloyd Wright, Orson Welles, and Georgia O’Keeffe, though all three quickly left, first for Chicago, then for warmer climes. (The state tourism board’s campaign “Escape to Wisconsin” has often been tampered with by bumper sticker vandals who eliminate the preposition.)

More recently, Wisconsin is starting to become known less for its ever-struggling left-wing politics or artistic figures—Thornton Wilder, Laura Ingalls Wilder—than for its ever-wilder murderers. The famous late-nineteenth-century “Wisconsin Death Trip,” by which madness and mayhem established the legend that the place was a frigid frontier where inexplicably gruesome things occurred—perhaps due to mind-wrecking weather—has in recent decades seemingly spawned a cast of killers that includes Ed Gein (the inspiration for Psycho), the serial murderer and cannibal Jeffrey Dahmer, and the two Waukesha girls who in 2014 stabbed a friend of theirs to honor their idol, the Internet animation Slender Man.

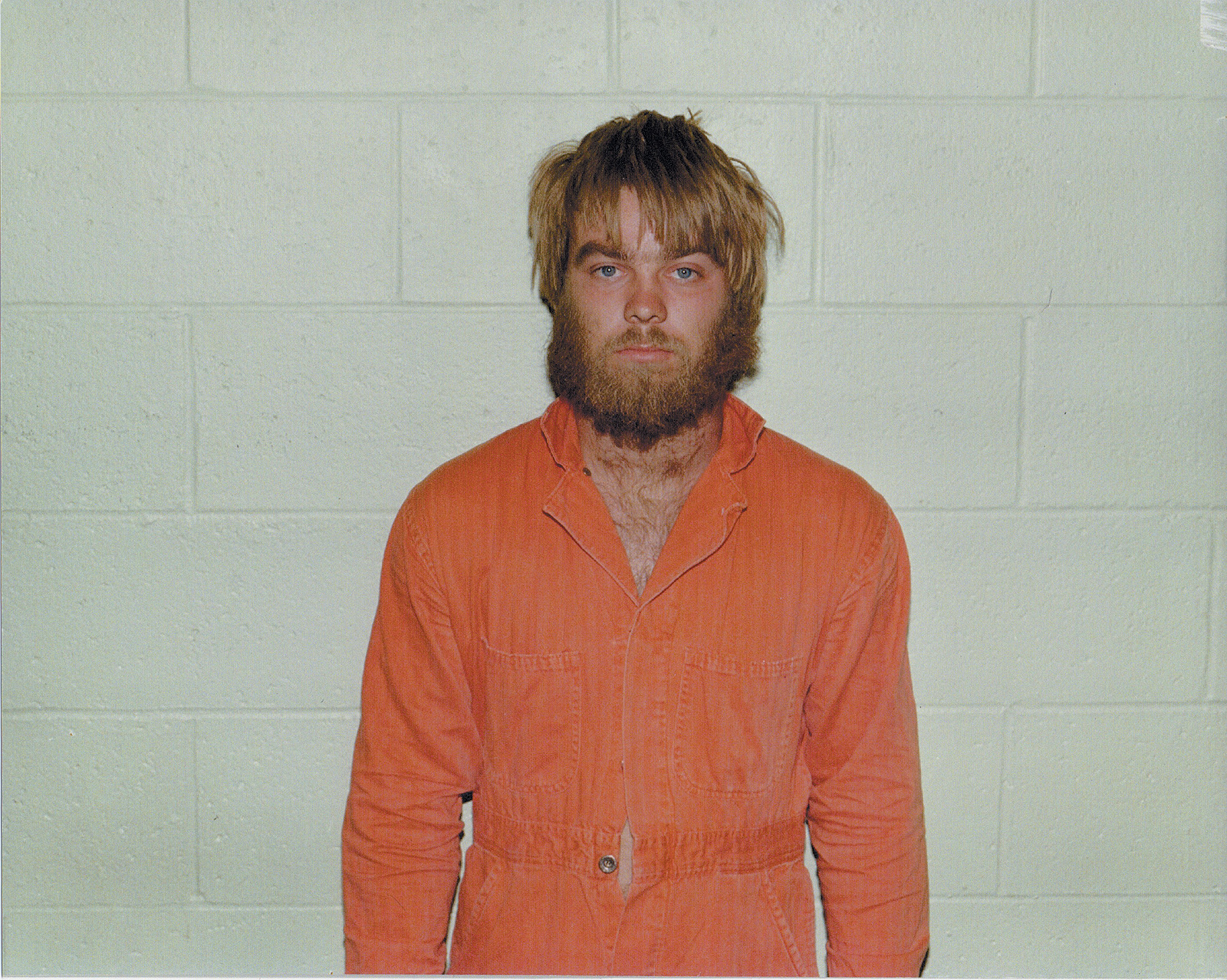

The new documentary Making a Murderer, directed and written by Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, former film students from New York, is about the case of a Wisconsin man who served eighteen years in prison for sexual assault, after which he was exonerated with DNA evidence. He then became a poster boy for the Innocence Project, had his picture taken with the governor, had a justice commission begun in his name—only to be booked again, this time for murder.

Ricciardi and Demos’s rendition of his story will not help rehabilitate Wisconsin’s reputation for the weird. But it will make heroes of two impressive defense attorneys as well as the filmmakers themselves. A long-form documentary in ten parts, aired on Netflix, the ambitious series looks at social class, community consensus and conformity, the limits of trials by jury, and the agonizing stupidities of a legal system descending on more or less undefended individuals (the poor). The film is immersive and vérité—that is, it appears to unspool somewhat in real and spontaneous time, taking the viewer with the camera in unplanned fashion, discovering things as the filmmakers discover them (an illusion, of course, that editing did not muck up). It is riveting and dogged work.

The film centers on the Avery family of Manitowoc County, home to the aforementioned ferry to Michigan. Even though the lake current has eroded some of the beach, causing the sand to migrate clockwise to the Michigan dunes, and the eastern Wisconsin lakeshore has begun to fill forlornly with weeds, it is still a picturesque section of the state. The local denizens, whether lawyers or farmers, speak with the flat a’s, throatily hooted o’s, and incorrect past participles (“had went”) of the region. There is a bit of Norway and Canada in the accent, which is especially strong in Wisconsin’s rural areas and only sometimes changes with education.

The Avery family are the proprietors of Avery’s Auto Salvage, and their property—a junkyard—on the eponymous Avery Road is vast and filled with over a thousand wrecked automobiles. It is a business not unlike farming in that in winter everything is buried in snow and unharvestable. The grandparents, two children, and some grandchildren live—or used to—on an abutting compound that consists of a small house, a trailer, a garage, a car crusher, a barn, a vegetable garden, and a fire pit.

In 1985 Steven Avery, the twenty-three-year-old son of Dolores and Allan Avery, was arrested and convicted of a sexual assault he did not commit. There was no forensic technology for DNA testing in 1985, and he had the misfortune to look much like the actual rapist—blond and young—and the traumatized victim, influenced by the county investigators who had the whole Avery family on their radar, identified him in a line-up as her attacker. Despite having sixteen alibi witnesses, he was found guilty. The actual rapist was allowed to roam free.

Advertisement

After the Wisconsin Innocence Project took on his case, Avery was finally exonerated in 2003. DNA tests showed he was not guilty and that the real attacker was now serving time for another rape. Avery then hired lawyers and sued Manitowoc County and the state of Wisconsin for wrongful imprisonment and for denying his 1995 appeal (a time during which DNA evidence might have set him free), which the state had mishandled, causing him to serve eight more years.

Days after Avery’s release, Manitowoc law enforcement was feeling vulnerable about the 1995 appeal and writing memos, redocumenting the case from eight years earlier. The civil suit was making headway, and only the settlement amount remained to be determined; it was going to be large and would come out of Manitowoc County’s own budget, since the insurance company had denied the county coverage on the claim.

Then, in November 2005, just as crucial depositions were both scheduled and proceeding and Avery stood to receive his money, he was suddenly and sensationally arrested for the murder of a freelance photographer named Teresa Halbach, who had come to Avery’s Auto Salvage on Halloween to photograph a truck for an auto magazine, and whose SUV had been found on the Avery property, as eventually were her scattered and charred remains. Avery had two quasi alibis—his fiancée, to whom he’d spoken at length on the phone the afternoon of Halbach’s disappearance, and his sixteen-year-old nephew, Brendan Dassey, who had just come home from school.

No one but Steven Avery ever came under suspicion, and county investigators circled in strategically. After getting nowhere with the fiancée, they focused on the nephew, who was gentle, learning-disabled, and in the tenth grade; they illegally interrogated him and suggested he was an accomplice. They took a defense witness and turned him into one for the prosecution.

Brendan was then charged with the same crimes as Avery: kidnapping, homicide, mutilation of a corpse. Prodded and bewildered, Brendan had made up a gruesome story about stabbing Halbach and slitting her throat in Avery’s trailer (the victim’s blood and DNA were never found on the premises), a fictional scenario that came, he later said, from the James Patterson novel Kiss the Girls. When asked why he’d said the things he said, he told his mother it was how he always got through school, by guessing what adults wanted him to say, then saying it. In an especially heartbreaking moment during the videotaped interrogation included in the documentary, and after he has given his questioners the brutal murder tale they themselves have prompted and helped tell, Brendan asks them how much longer this is going to take, since he has “a project due sixth hour.”

It is a crazy story. And the film’s double-edged title pays tribute to its ambiguity. Either Steven Avery was framed in a vendetta by Manitowoc County or the years of angry prison time turned him into the killer he had not been before. But the title aside, the documentary is pretty unambiguous in its siding with Avery and his appealing defense team, Jerry Buting and Dean Strang, who are hired with his settlement money as well as money his parents, Dolores and Allan, put up from the family business.

One cannot watch this film without thinking of the adage that law is to justice what medicine is to immortality. The path of each is a little crooked and always winds up wide of the mark. Moreover, nothing is as vain and self-regarding as the law. In Wisconsin prisoners will not get their parole unless they sign formal admissions of guilt and regret. (This kept Steven Avery from his own release when he was younger; he clung to his innocence.) These exacting corrections procedures are almost religious and certainly Orwellian in their desire to purge the last contrarian part from the human spirit. Any contempt for the law—even by a lawyer in court—will not go unpunished. And if one has the further temerity to use the law against itself—filing a lawsuit against law enforcement, for instance—one should be fearful. Especially in Manitowoc. Or so say many of the locals in front of Demos’s camera.

As portrayed in Making a Murderer, however, the law is not so vain that it doesn’t point out the low IQs of the defendants (an IQ test, it could be asserted, largely measures the desire for a high IQ) while omitting the fact that in Wisconsin most lawyers are practicing law without ever having taken a bar exam. (If someone has attended law school in the state, the bar exam is not required to practice there—a peculiarity of Wisconsin.)

Advertisement

If the film does not do a good job in positing an alternative theory of the murder—surely it does not believe the sheriff’s department killed Teresa Halbach, or does it?—this is because the filmmakers are busy following the charismatic Buting and Strang in their courtroom defense and pre-trial investigation. These are men of the finest skepticism. In their skilled and righteous run at the state they also seem the only ones in the film in possession of cool, deep, permanent mental health, and thus these ordinary-looking men suddenly resemble movie stars. A Twitter love-fest has sprung up around them, beginning soon after the documentary first aired, and their faces have been posted online accompanied by girlish hearts and declarations of love.

But handsome is as handsome does, and Buting and Strang are not allowed to suggest that others might have committed the crime—due to a Wisconsin law involving third-party liability. And thus everyone’s hands are tied. The trial must proceed as one that is about police corruption and reasonable doubt. Nonetheless we see any number of suspicious civilians with odd affects who may or may not have had the means, motive, and opportunity for murder.

Halbach’s killing is largely presented as a motiveless crime, though her brother, her ex-boyfriend, and a couple of Avery family members are seen on camera with odd expressions and bewildering utterances. (“Odd Affect” could be the film’s subtitle and would certainly describe the demeanor of many of the court-appointed attorneys as well.) Halbach’s roommate did not report her missing for almost four days. Her former boyfriend is never asked for an alibi, and can’t remember precisely when he last saw her. Was it morning or afternoon? He can’t recall. Nonetheless he was put in charge of the search party that was combing the area near the Avery property in the days after she was finally reported missing.

So who did this? Possibly Steven Avery. But it looks like a crime that can never be properly solved. The story Avery’s defense team tells of law enforcement planting evidence is completely convincing, and such conduct is hardly unprecedented in tales of true crime. The Averys were not allowed on their own property for eight days while police roamed and rooted around, after which the scattered cremains, Avery’s blood in the victim’s car, and the victim’s spare car key were all “discovered.” Blood taken from Avery in 1995 was also found to have been tampered with in police storage.

But showing that there was police-planted evidence does not solve the crime; it only underscores its Not Proven status for purposes of a courtroom defense. And so the filmmakers’ story—if it is a crime story, a human story—is missing parts. One may be struck by the complete absence of drugs and drug business in a neck of the woods where such activities often feature prominently. The victim’s personal life is almost completely missing and so she seems a tragic cipher.

And although she and her scarcely seen boyfriend are broken up, he still figures out how to hack into her cell phone account and attempts with anxious nonchalance to explain on camera and on the stand how he did so, though it seems to have been done with some extremely lucky guessing involving her sisters’ birth dates. Messages are found deleted. This seems more damning than the three calls Avery himself made to Halbach, returning a call from her the day she disappeared. The fact of Avery’s calls to Halbach was left out of the film (though it was offered as evidence in the trial), as if the filmmakers themselves were unreasonably, narratively afraid of it.

Early on, because of Avery’s civil suit, Manitowoc investigators were ordered by the state to allow neighboring Calumet County to do the primary investigation into the murder: conflict of interest, due to the wrongful imprisonment civil suit, was recognized from the start. But this was not enforced and Manitowoc sheriffs did not stay away, and the opportunities for evidence-planting were myriad. The prosecutor and even the judges are seen to proceed with bias, professional self-interest, visible boredom, and lack of curiosity. At one point the special prosecutor is seen in the courtroom staring off into the middle distance, playing with a rubber band.

The story one does see clearly here is really a story of small-town malice. The label “white trash,” not only dehumanizing but classist and racist—the term presumes trash is not ordinarily white—is never heard in this documentary. Perhaps the phrase is too southern in its origins. But it is everywhere implied. The Averys are referred to repeatedly by others in their community as “those people” and those “kind of people.” “You did not choose your parents,” says an interrogator, trying to ply answers out of sixteen-year-old Brendan, though his parents are irrelevant to the examination and are not being criminally accused of anything.

Yet the entire family is socially accused: outsiders, troublemakers, feisty, and a little dim. What one hears amid the chorus of accusers is the malice of the village. Village malice toward its own fringes has been dramatized powerfully in literary and film narrative—from Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible to the Michael Haneke film The White Ribbon to Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games. Trimming the raggedy edges is how a village stays a village, how it remains itself. Contemporary shunning and cleansing may take new and different forms but they always retain the same heartlessness, the unacknowledged violence, the vaguely genocidal thinking. An investigator ostensibly on Brendan’s defense team speaks openly of his distaste for the Avery family tree and says, “Someone said to me we need to end the gene pool here.”

The German word Mitläufer comes to mind: going along to get along, in a manner that does not avoid misdeeds—one of the many banalities of evil. Certainly one feels that frightened herd mentality among the Manitowoc law enforcement as well as members of the jury, the majority of whom were initially reasonably doubtful but who, swayed by a persuasive minority, soon unified to a unanimous vote of guilty. Even the jury in Brendan’s trial did not question the nature of the defendant’s several and contradictory confessions, such was their prejudice against the boy.

It may or may not be useful to recall that early German settlers of Wisconsin, escaping the nineteenth-century military autocracy in Europe, once believed that the American Civil War would break up the Union, producing some independent states that could then come under German rule. These ordinary German citizens did not get their own state, of course, and in fact had to share it with Scandinavians, Poles, and even Bulgarian and Cornish miners, but certain stereotypical German burgher traits—from rule-boundedness to tidiness to anti-Semitism—are sometimes said to have persisted in Wisconsin life. (A shocking number of Nazi sympathizers once resided in Milwaukee.) A reputation for niceness may obscure rather than express the midwestern character.

When watching two New Yorkers construct a film about the sketchy Wisconsin legal system one may overreach for cultural memes. (Cogent thesis-making is not this film’s strong point, or its mission, and so a viewer is likely to veer off independently. Thus the Internet and media are full of armchair sleuths and amateur psychologists in the growing discussion of the film.) But conformity and silence on the job are elements in this tale, and they are timely subjects. Businesswoman and amateur social scientist Margaret Heffernan has recently been publicizing the results of her workplace survey of “willful blindness.” According to Heffernan, 85 percent of people know there is something wrong at work but will not come forward to report or discuss it. When she consulted with Germans they said, “Oh, yes. This is the German disease.” But when she consulted with the Swiss she was told, “This is a uniquely Swiss problem.” In the UK: “The British are really bad at this.” And so on. Willful blindness is everywhere, though touched on only glancingly in the film.

And so it comes as something of a surprise that what the documentary does linger over most single-mindedly—either deliberately or unconsciously—is the theme of mother love (perhaps not unrelated to willful blindness on the job). It is not just Brendan’s mother Barb who is her son’s impressively fierce defender. Barb is described by her son’s lawyer as a bulldog, and clearly the lawyer is afraid of her. In her close protectiveness toward Brendan she quickly understands that he is ill-served by the court-appointed defense.

But the filmmakers’ story is also of Steven Avery’s aging and devoted mother Dolores, who packs up boxes of photocopied letters and transcripts and sends them everywhere—from Sixty Minutes to 20/20—hoping to get some journalists interested in her son’s case. The effect of the media is a fraught one in this film—local TV news influenced many of the jurors, and the prosecution often used the press to communicate in unethical ways. Making a Murderer has invited parallels to the podcast Serial, which has recently, and intrusively, played a role in getting a convicted murderer a new hearing, though the evidence in that case was much more substantial: a crime of passion by a jealous and brokenhearted boy. The Teresa Halbach case is more mystifying.

Meanwhile, short and lame and chewing on her lips, Dolores Avery visits her son in three different prisons in Wisconsin and one in Tennessee. She speaks to him on the phone regularly and optimistically. In her fruit-printed housedresses and floral shirts she faces the camera and conducts calm tirades against the legal system that has taken her son away. The filmmakers give her more screen time than anyone would ordinarily expect—and she and her husband close the documentary with a sense of domestic resilience. Their son and grandson are in prison for murder. Their business has gone under. Yet they will continue. Arm in arm! A vegetable garden of kohlrabis! A smile of faith and hope! The film is in the grip of its own sentimental awe. But there are worse things in the world.

This Issue

February 25, 2016

The Psychologists Take Power

A New Deal for Europe