In late April, Yale President Peter Salovey announced that the university would not change the name of Calhoun College, a residential college named after John C. Calhoun. Calhoun, a Yale graduate and a leading politician and political theorist of the nineteenth century, served as a member of the House of Representatives, senator, vice-president under Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, secretary of war, and secretary of state. He was also an avowed defender of slavery, states’ rights, and nullification.

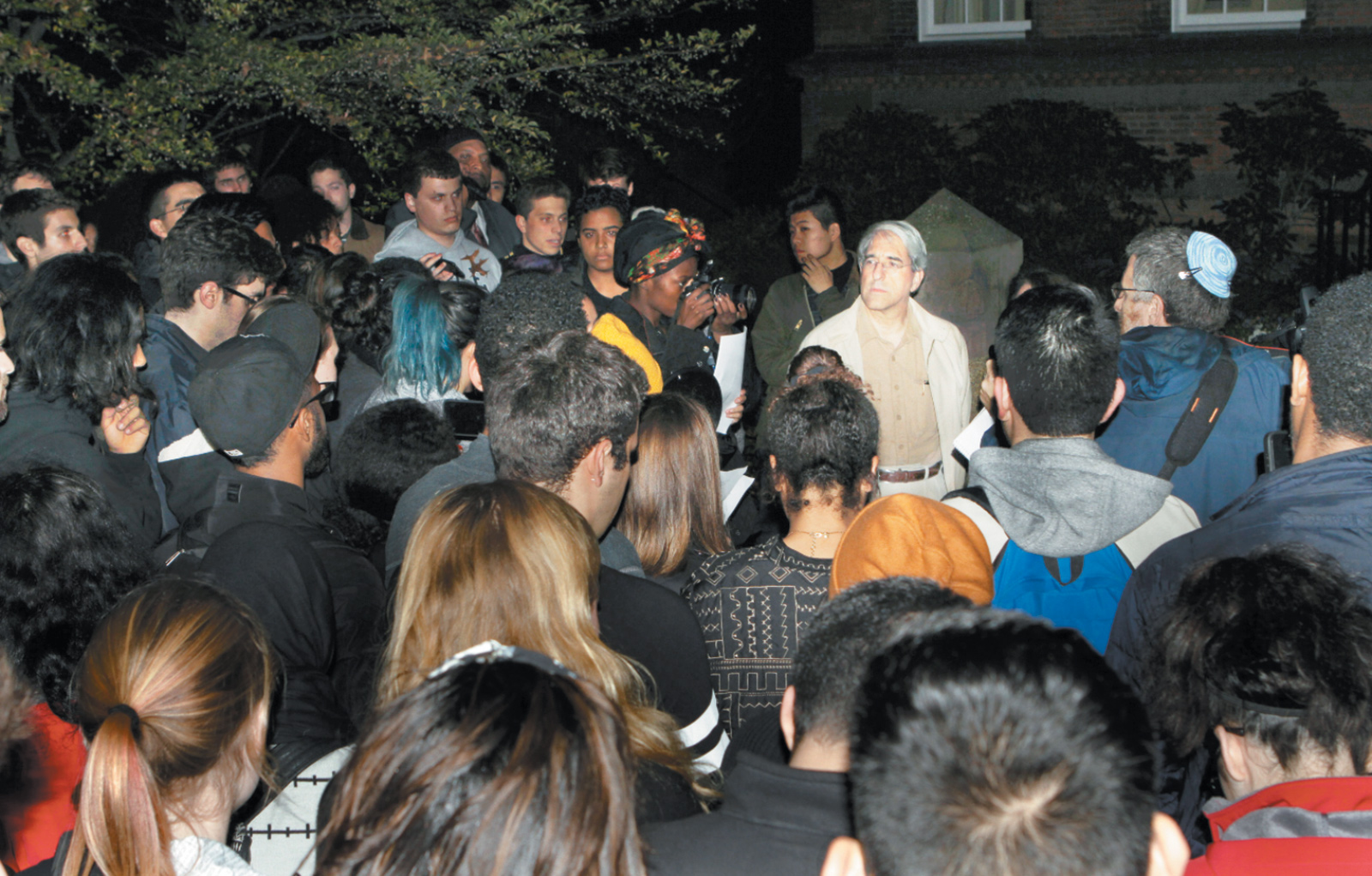

Last fall, students of color and others launched protests about the lack of diversity and racial inclusion at Yale, one of many student protests across the nation. Among other things, Yale students asked for greater diversity in faculty and more resources for racially identified cultural centers and courses. (Of 655 tenure-track professors in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, twenty-four, or 3.7 percent, are African-American, and eighteen, or 2.7 percent, are Hispanic.) The students also called for Calhoun College to be renamed, for the abandonment of the term “master” for heads of residential colleges, and for the dismissal of one associate master, Erika Christakis, because of a letter she had written defending the rights of students to wear offensive costumes on Halloween.

In November, President Salovey responded to the protests by announcing a series of structural reforms, including more funding for four minority student cultural centers, the creation of an academic center for the study of race, the hiring of new faculty, and training for Yale administrators in recognizing and combating racial discrimination. He declined to remove or otherwise punish Erika Christakis (who later decided not to continue teaching in Yale College, while maintaining her work as associate master of Silliman College and as a faculty member in the Yale Child Study Center). He put off decisions on the term “master” and Calhoun College until he could gather the views of community members.

In the meantime, students at Princeton called for the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs to be renamed because of Wilson’s racist views; students at Harvard Law School demanded that the school abandon its shield, which featured the crest of the Royalls, a slave-owning family that had donated to the law school; and students at Amherst called for discontinuing the school’s unofficial mascot, Lord Jeff, because his namesake, Lord Jeffrey Amherst, had urged the delivery of smallpox-infested blankets to Native Americans in the colonial era. Harvard recently decided to drop the Royall family crest, and Lord Jeff is no longer Amherst’s mascot. Princeton, however, chose to keep the name of the Woodrow Wilson School.

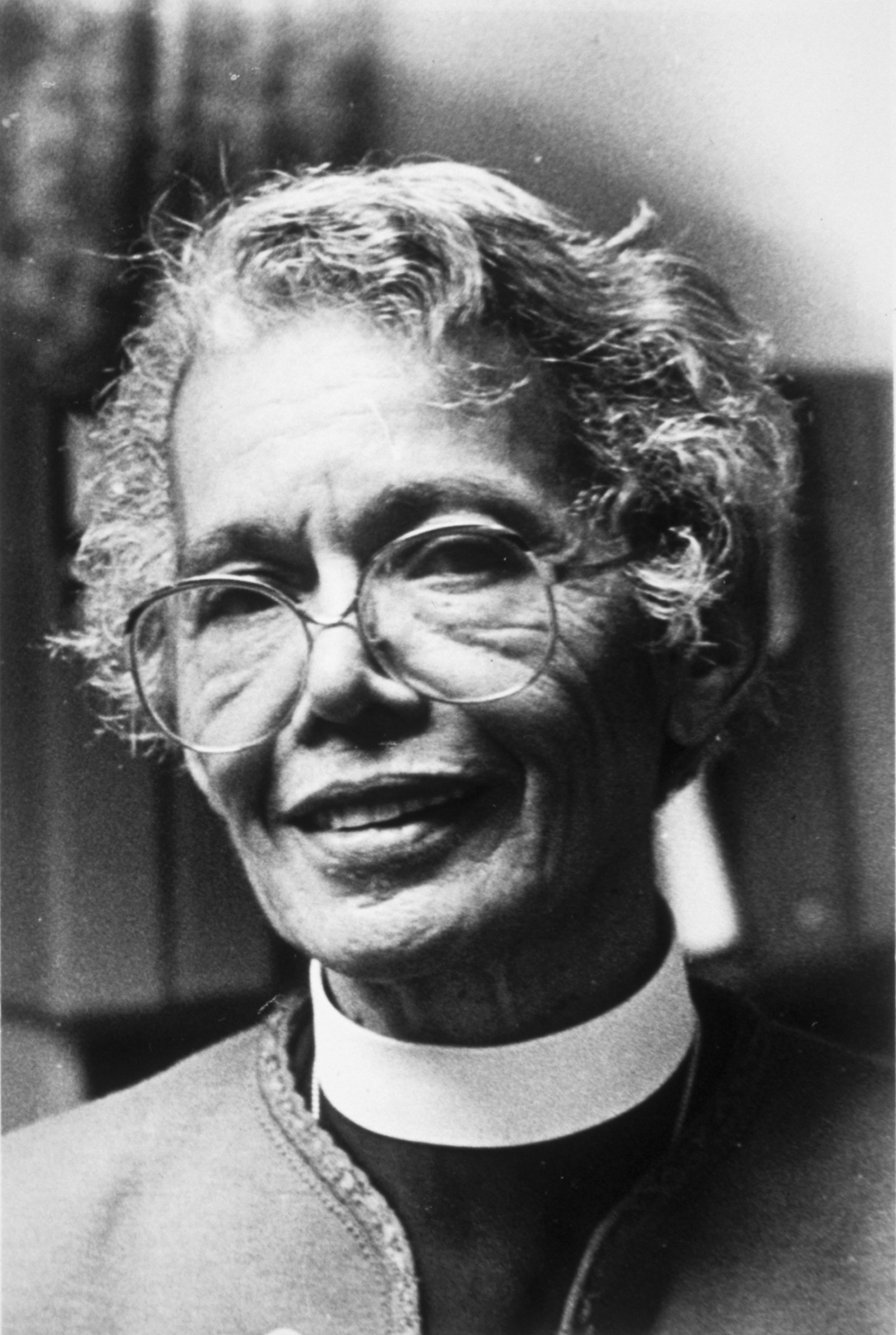

Yale decided to retain the name of Calhoun College, but to stop using the term “master” for heads of residential colleges. It simultaneously announced that it would name two new residential colleges for Anna Pauline Murray, an African-American civil rights activist, and Benjamin Franklin. To explore the issue of how educational institutions should address their own checkered histories and those of their namesakes, and what can and should be done to foster a more racially tolerant environment on college campuses, I spoke with Salovey about his decisions, and about the broader issues presented by the student protests that occurred at Yale and many other campuses this past year.

David Cole: You recently announced that Yale will not change the name of Calhoun College, despite its namesake’s vigorous defense of slavery. Why did you choose to retain the name?

Peter Salovey: The debate about the name of Calhoun College has gone on intermittently for many years. Calhoun was a defender of slavery, and he defended it not just as a necessary evil, but as a “positive good.” So this was not an easy decision. We listened to students, faculty, alumni, and staff. We’ve had multiple conversations among the trustees. But this isn’t the kind of question you can put to a vote. You have to decide what is the right principle for an educational institution.

To me, the principle that is most compelling is that we should attempt to confront our history in order both to learn from it and to change the future. We shouldn’t obscure our history, or run from it. And when I say “our history,” I mean our nation’s history, but also Yale University’s history. There is no doubt that Calhoun’s views on slavery are repugnant. But to me the appropriate response is to ask what we can learn about the history of racism in this country, and thereby motivate ourselves to work toward a better future. We do that by learning about Calhoun, by confronting Calhoun, not by pretending that he didn’t exist.

Advertisement

Cole: How do you propose to confront that history in a public way, since for years the college has celebrated Calhoun in a public way? Will the confrontation be equally public?

Salovey: Yes, I think so. I would not call naming a residential college for Calhoun necessarily celebrating him, although it does memorialize him. Our plan is both to include on the Calhoun College grounds an art installation that will confront Calhoun’s ideas and to launch a history project at Yale that will make visible aspects of this campus’s history, both those that we can be proud of but also those that we now find disturbing. And we can’t just focus on Calhoun. We need to examine many of our namesakes and many historic moments on this campus and learn from them. Any 315-year-old institution in this country is going to discover aspects of its own history about which it is now not proud. I was very concerned that hiding them away, starting with Calhoun, would simply make it less likely that we would teach our own history.

Cole: Do you think that uncovering history is sufficient? And if not, what more can Yale or any other university do to respond to its own involvement in historic racial injustices?

Salovey: Revealing that history is only the first step. Teaching it in the context of larger struggles is the next step and then using it to guide us as we go forward in a principled way is very important. We can learn about ourselves not only from what Calhoun had to say about slavery in the first part of the nineteenth century, as challenging as that is to our twenty-first-century ears, but also by talking about how decisions to memorialize on this campus were made. The decision to name Calhoun College was made not in 1850, but around 1930. And we can learn from the conversations that took place or did not take place at that time as well.

Cole: Do you know whether any objections were raised in the 1930s based on Calhoun’s role in defending slavery?

Salovey: As far as we can tell they were not.

Cole: You have also announced that Yale is going to name its two new residential colleges after Anna Pauline Murray, a civil rights activist, and Benjamin Franklin. Do you see that naming exercise speaking to the controversy over racial inclusion?

Salovey: Yes I do. In naming colleges for Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin we selected two public figures who in their time and in very different ways spoke out against slavery and discrimination. They both embraced the idea of education as salvation. They were both intellectuals, and they embodied an orientation toward lifelong learning. Obviously, Pauli Murray herself brings more diversity to the names that our buildings bear. It’s important not to look at these two buildings as the last two that will be named on this campus. We have opportunities to continue to try to embrace the diversity of contemporary Yale and include names that better reflect that diversity down the line.

Cole: Are there other buildings on campus right now that have the names of people of color or women?

Salovey: Yes. Helen Hadley Hall, a graduate dorm, for example, is named for a woman. The Rose Center, a community center and Yale police headquarters on campus, is named for alumna Deborah Rose. But there clearly could be more and will be more.

Cole: I understand the choice of Pauli Murray, who was a powerful advocate for women’s rights and African-American rights, but why Ben Franklin? He didn’t go to Yale, he’s yet another white man, and he did own slaves, didn’t he?

Salovey: Yes, Franklin owned slaves during part of his life. However, his beliefs changed quite dramatically and by the end of his life, when he no longer owned slaves, he became the president of the Abolitionist Society in Philadelphia, and wrote a petition to Congress arguing for the abolition of slavery. He has an honorary degree from Yale and carried on a long correspondence with Ezra Stiles, an early president of Yale. And Yale is the home of the Benjamin Franklin papers. So there’s an interesting connection between Franklin and Yale.

Finally, these colleges would not have been built without the generosity of a 1954 Yale graduate named Charlie Johnson.* He gave to Yale its largest gift ever by a single individual. That gift is going to allow thousands of students to get an education at Yale who otherwise wouldn’t have had that chance. Benjamin Franklin is a personal hero to Charlie Johnson. So one consideration in naming the colleges was to find a way to honor and express our gratitude toward him.

Cole: Why did you change the title of “master” for the heads of the residential colleges?

Advertisement

Salovey: The principle that guided us is that we don’t want to distort or mask our history, especially those aspects about which we are not proud. Changing the name Calhoun would have violated that principle, but discontinuing “master” does not. “Master” is actually not a term with much historical resonance at Yale. It comes from the fact that when our residential colleges were built in the 1930s, our models were Cambridge and Oxford. And that’s what the heads of the colleges at Cambridge and Oxford were and still are called.

The word “master” comes from the Latin for “teacher.” There’s nothing inherent in the word that’s a problem. But in this country it also has the connotation of an owner of slaves, and I think it is very hard for students to call their residential college head “master.” It is cringe-worthy for administrative staff, custodians, and dining hall workers to call the head of the college where they work “master” in this day and age. The masters themselves had become uncomfortable with the title and wanted it changed. The difference between these two issues is their historical significance: Are you hiding something by making the change? I think in the case of Calhoun we would be. In the case of “master” we’re not.

Cole: I’d like to move on now to the broader lessons from the protests last fall at Yale. As you know, similar protests took place on many campuses across the country. Why now?

Salovey: The media’s obsessive focus on specific triggering events on many campuses causes us to miss the larger issues. There is no doubt that social media accelerated the sharing of information among students and the organizing of protests. But more significant is what is on eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds’ minds when they come to campus today. Students from underrepresented minority groups in particular arrive having witnessed videos and read reports of unarmed individuals of their age and color dying at the hands of law enforcement officers. They think about who disproportionately populates our prisons.

They think about how a case is in front of the Supreme Court now that might bar the consideration of race or ethnicity in admissions decisions at colleges and universities. They think about the fact that the high schools they attended might have been more integrated twenty-five years ago than they are today. They think about the way political figures running for public office talk about race and ethnicity in disparaging terms. All of that contributes to a heightened awareness of slights, insults, and other incidents on campus that make their minority status salient. That’s what I think we were seeing on campuses across the country this fall.

Cole: Some commentators have belittled the students’ complaints, particularly in light of their privileged status as Yale students.

Salovey: Taken out of context, any single incident might appear to be relatively minor, but the experiences can and do accumulate over time. Students talk to me about returning home to their residential colleges at night and gates being shut and locked in front of them by a classmate because they don’t “look like a Yale student.” Students tell me about classrooms where they are asked to speak on behalf of their ethnicity, race, or nationality, as if they somehow represent a uniform view. Students talk about observing segregated social scenes. At the end of the day, all our students want to feel that they belong and that they have the same access to a great education as everyone else. In their hearts they know that’s possible, but they want to be reassured that it is. And we have to take that seriously. Are our students privileged to be here? Of course they are. But Yale is not walled off from the real world. It is part of the real world.

Cole: Might part of the problem for students of color at Yale stem from the gap between Yale as a bastion of privilege and New Haven as an urban center beset by poverty and crime? And are there things Yale can do to address that gap?

Salovey: Our host city, New Haven, has the challenges that any urban area in the United States has. We are diverse, ethnically and economically. We have challenges of poverty in the midst of wealth. We have challenges of public schooling and housing.

Yale tries to be a partner with the city in many ways. We make more voluntary payments to our city than I believe any other university makes to its host city. We pay for a program that provides scholarships to every graduate of a New Haven public high school with a certain GPA, attendance record, and level of community service to attend any college or university in Connecticut. We have a home buyer program that has provided 1,100 of our employees a significant contribution toward the purchase of a home in the city.

Our students and faculty have created new business ventures that we hope will remain in the city and help it develop economically, such as Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Higher One, a financial services company aimed at assisting college students nationwide. And when you compare changes in income, population growth, and other indicators of economic health, New Haven is doing far better than the other cities in this state. Finally, about 75 percent of our undergraduates volunteer in New Haven. They are tutors in schools, they work for literacy programs, they coach, they work on housing. I think our level of community service is as high as one would find on any college campus in the country.

Cole: But isn’t the problem of Yale in New Haven just a specific instance of the much broader problem of the wealth gap in our society today? And on that score, aren’t elite private universities arguably as much a part of the problem as of the solution?

Salovey: There is no doubt that the distribution of wealth in this country is disturbing to this generation of students. But in my view, universities can and should be part of the solution. Part of the way to address income disparities is by providing education. Yale offers an education without financial burden to working-class and middle-class families. For many students it makes possible upward social mobility from their parents’ generation as well as access to an intellectually richer life.

About 15 percent of our students are the first in their family to go to college. The number of our students who are eligible for federal Pell Grants for low-income families has gone up by more than 40 percent since I became president. In last year’s freshman class, more than 18 percent of our students who were US citizens or permanent residents qualified for a Pell Grant. More than half of our undergraduates receive financial aid, and the average aid grant this year is $45,000. Pursuing and supporting such students is a way of addressing income disparities. In fact, our data show that disparities in family wealth at the time of admission shrink five years after graduation from Yale.

Cole: One of the principal concerns that has been raised about the recent student protests is whether creating an inclusive campus is at odds with freedom of expression and inquiry. In C. Vann Woodward’s report on free speech at Yale in the 1970s, he warned that “without sacrificing its central purpose, [a university] cannot make its primary and dominant value the fostering of friendship, solidarity, harmony, civility, or mutual respect.” To do so, he suggested, would contravene the goal of exposing students to challenging ways of thinking. Do you agree with that, and if so, how do you navigate the tension between making people feel comfortable and safe and ensuring that Yale remains, in Woodward’s terms, “a forum for the new, the provocative, the disturbing, and the unorthodox?”

Salovey: I absolutely agree with Woodward. In fact, my address welcoming the freshmen to campus in 2014 quoted that same passage. But I think it’s critical to recognize that inclusion and free expression are both important values and don’t necessarily represent a challenge to each other. The role of a university is not to protect students from speech but to educate them to find their voices. They can do that especially when they feel they are part of an inclusive campus.

Woodward goes on to say that, to be sure, friendship, solidarity, and harmony are important values, and a good university will seek to promote them, but it can’t let those values get in the way of free expression. That’s a really important point and I think many critics have missed it. We can value civility, respect, and inclusion, and we can do all of that by not compromising free expression if we take our role as educators seriously and help students develop the ability to speak back in response to ideas that they find offensive. That isn’t a compromise of free speech. It is free speech.

Cole: But some Yale professors have expressed concern that the climate of inclusion has made it more difficult to foster debate in the classroom, for fear that somebody will say something that will then be taken as offensive. Have you heard such remarks? And isn’t there a risk that you will make people less willing to speak frankly?

Salovey: I am sure there are people who feel uncomfortable talking about difficult issues involving ethnicity and the like, and who worry about offending, but as educators we can and must help students learn how to have those kinds of conversations more easily, less awkwardly, and more honestly. We must take seriously the fact that this is an educational environment and we are educators. The answer to speech that offends us is always our own speech—more speech. I recognize that that isn’t always comfortable and that it might be easier simply to be offended and angry than to respond and to argue back, but we have to help our students learn how to do that.

Our campus is committed to free expression. One of the best ways to teach this is by example—by tolerating the expression of unpopular ideas on campus. Even in the midst of this fall’s discussions about inclusion and student protests, people came to this campus and delivered addresses that featured unpopular ideas. Penn law professor Amy Wax was here speaking against affirmative action; Greg Lukianoff of FIRE, one of the principal critics of what he sees as politically correct campus climates, was here. No one at Yale during my tenure has had an invitation rescinded over what they’re going to say, and no one has been punished at Yale for expressing an opinion, whether they are faculty or students.

Cole: Let me turn to faculty diversity. One view is that part of the problem at Yale and many other schools is that the admissions office has succeeded in creating a much more diverse student body over the last decades, but that diversity in faculty has lagged behind. Do you think that’s right, and if so, why?

Salovey: I think it is true. I am not satisfied with the diversity of our faculty. And it lags the diversity of our student body. It’s a complicated challenge. We need to encourage more students from the undergraduate level on up to pursue careers in scholarship and teaching. We have to encourage prospective and young faculty by providing support and mentoring at every step: undergraduate, graduate, post doc, and junior faculty. We need to identify sources of bias in ourselves and in our processes and then we must look for potential faculty members in places where we may not have looked in the past.

Bringing in young scholars in small groups, sometimes called cluster hiring, is another innovative strategy. But simply rotating faculty from underrepresented groups around the same set of universities in higher education doesn’t solve the problem. We are delighted when new faculty members come to Yale from another university and bring diversity to our faculty, but that’s really just a zero-sum game unless we figure out a way to increase the supply of minority scholars.

Cole: Does your initiative include concrete steps to encourage underrepresented minorities to pursue scholarly careers?

Salovey: Yes. We have programs for our undergraduates and for our graduate students to encourage and support those who are interested in pursuing academic careers. For undergraduates, we have the STARS program, which supports women, minority, and economically disadvantaged students in science, engineering, and math, and the Mellon Mays Fellowships, which provide funding and research opportunities for minority students seeking academic careers. In January, we announced an Emerging Scholars Initiative, which will provide similar support in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Every department and school provides mentors to assist junior faculty members. Are we more successful than other universities? No. But all major universities are finding this a challenge.

Cole: You announced a $50 million initiative to increase faculty diversity before the fall protests. But a number of people with whom I spoke cited the school’s many prior diversity initiatives as a reason to be skeptical, because despite twenty years of diversity initiatives, Yale’s faculty diversity has not improved, and may have gotten worse, in part because of departures of some leading minority scholars. So how do you ensure that this time it’s going to be different? What kind of accountability mechanism is in place? How do you know it’s worked?

Salovey: It’s true that the numbers have not changed very much, particularly for African-American, Latino, and Native American faculty, over more than a decade, probably over two decades. It is not easy to do. We have far more support in the system this time for the identification of potential people to hire, we have devoted $50 million to the project, and we have individuals designated to be responsible and accountable for improving the diversity of their schools and departments in the current approach that we didn’t have last time. And we are also addressing some of the collateral issues and barriers that get in the way of hiring a diverse faculty. We are monitoring ourselves, tracking ourselves, and holding hiring committees accountable.

Cole: One of the demands that the students made that you didn’t accept was to amend Yale’s distribution requirements to include an ethnic studies requirement. Why not, and what sort of curricular reforms do you think are appropriate?

Salovey: Yale, like every college or university I know, places the responsibility for curriculum in the hands of the faculty, so it’s the faculty’s call. Many faculty members feel that courses in ethnic studies, broadly defined, would be of great value for students, but that having them find them on their own initiative rather than being compelled to take them yields a much more educational classroom environment.

We’re seeing that happen now. Since the fall there’s been a very significant uptick in the enrollment in ethnic studies courses, such as Introduction to American Indian History and Introduction to Latino/a Studies. In fact, we’ve had to hire additional faculty to teach such courses. So I think there’s a way to accomplish this goal without imposing new requirements.

Cole: You doubled the funding for the college’s four minority cultural centers. Do you think there is any basis for concern that such centers may increase segregation on campus?

Salovey: I don’t think so. I have felt for quite some time, really since my days as the dean of Yale College, that the funding for our cultural centers was not keeping pace with the increased diversity of our student body, so I feel very comfortable augmenting their resources. They play a very important role in campus life. Rather than isolating students from the rest of campus, I believe they empower our students to engage in the rest of campus life. It’s also important to remember that people of all ethnicities can and do use the cultural centers.

I remember talking to a particular student a number of years ago in a cultural center. I asked him, “You know, cultural centers are always controversial, what do you think is the proper role of a cultural center?” And he said, “Look, I grew up in a community of people who were just like me, and where the friends of my parents were just like them. I came to Yale because I wanted to be in a diverse student community, and after Yale I want to interact with people from all walks of life. I eat in my cultural center a couple times a week to feel the self-confidence that comes from hanging out with people who are similar to me, but I then use that self-confidence to branch out, and spend the other five evenings a week engaging with students that are not at all like the friends I grew up with.”

Cole: You’ve undoubtedly devoted many more hours to these issues than you might have expected when you became president. What have been the most rewarding parts of responding to the fall protests?

Salovey: The most rewarding part has been that the protests led to a real engagement around the issue of inclusion with faculty, students, and alumni throughout the Yale community. People are not all going to agree about the nature of the problem or the best way forward. But I think many people of good will are taking these concerns seriously. We’re having searching conversations at a level that I haven’t seen before.

-

*

Johnson served as chairman of Franklin Resources, a mutual fund company that was itself named after Benjamin Franklin. ↩