1.

Let us hear no more…of Ulysses and Aeneas and their long journeyings, no more of Alexander and Trajan and their famous victories. My theme is the daring and renown of the Portuguese, to whom Neptune and Mars alike give homage.

The words are those of Portugal’s national poet, Luís de Camões, in the dedicatory prologue to his epic poem The Lusiads (1572).1 If his epic is a hymn of praise to the achievements of the Portuguese as a people who wrought mighty deeds in far-off lands, its hero is Vasco da Gama, whose ships anchored off the southwest coast of India on May 20, 1498, after a 309-day voyage from Lisbon that took him around the Cape of Good Hope, up the coast of East Africa, and across the Indian Ocean to the Indian port of Calicut. That voyage would come to be seen as an epoch-making event, marking the beginning of a new age in the history of both Portugal and the world.

In Conquerors, Roger Crowley, who has won acclaim for his vivid narrative accounts of conflict in a Mediterranean world contested between Christendom and Islam,2 now follows Vasco da Gama and his immediate successors as they move far beyond the confines of Europe and lay the foundations of the first global empire in world history. This was the achievement of Portugal, located on the western rim of Europe, a country with little more than a million inhabitants in the middle years of the fifteenth century when the story of their overseas voyages begins in earnest. “Their achievement,” writes Crowley in his prologue, “has largely been overlooked.”

This is nonsense. Not only have the origins and establishment of Portugal’s overseas empire received an almost obsessive amount of attention from generations of Portuguese historians from the sixteenth century to our own, they have also generated an extensive English-language literature. In the nineteenth century the Hakluyt Society began the publication of English translations of texts relating to Portugal’s overseas voyages, including, in 1898, A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499.

The famous British historian Charles Boxer devoted much of his remarkable life to the study of the Portuguese empire. The crowning achievement of the no less remarkable British Hispanist Peter Russell was his iconoclastic study of the life of Henry the Navigator, and recent years have seen the appearance of valuable surveys of Portuguese imperial history in English.3

What, then, does Crowley contribute to an already extensive literature? He is well versed in both the primary and the secondary sources, and his knowledge of the late medieval and early modern world allows him to relate the creation of the Portuguese empire to the broader themes of European and world history in his chosen period. For instance we begin, very strikingly, with the appearance in Beijing on September 20, 1414, of the first giraffe ever seen in China, an exotic trophy brought home by one of the succession of fleets sent out by the Ming dynasty in the first three decades of the fifteenth century to the coastal states surrounding the Indian Ocean, before it restricted these long-distance voyages. I must confess, however, that I have not found in the book information or insights that are not to be found elsewhere. What the book does, and does extraordinarily well, is to tell a story that is exciting in itself and possesses enormous implications for the future.

Crowley is particularly good at evoking the sights and sounds of battle, both on land and at sea. Of Afonso de Albuquerque’s struggle in 1511 to capture the great trading center of Malacca on the western coast of the Malay Peninsula, he writes:

Fighting for the bridge became fierce, with Albuquerque’s men advancing rapidly. On the other side, as the Portuguese finally stormed the barricade, the sultan decided to enter the contest in person. His twenty war elephants came rampaging down the street, smashing everything in their way, followed by a large body of men. From their castles, archers shot arrows down on the intruders, the mahouts urging on their beasts, which had swords swinging from their tusks…. In the face of this terrifying cohort, the Portuguese started to retreat. Just two men stood their ground, confronting the enraged elephant of the king with their lances. One stabbed it in the eye, the other in the stomach.

And so it goes on. We can hear the roars of the wounded elephant and see, hear, and sense the “pandemonium and wild trumpeting” among the elephants that followed. The book abounds in set pieces of this kind, and all those who enjoy great storytelling will revel in his narrative.

In telling his story Crowley has the advantage of being able to quote from a wide range of contemporary or near-contemporary sources, in the form of correspondence and chronicles, which gives it a freshness that it would otherwise have lacked. Thus we find ourselves, with growing discomfort, in the company of motley bands of Portuguese fidalgos (gentry), mariners, soldiers, and ex-convicts, as they suffer the pangs of hunger, face shipwreck, board the vessels of Asian merchants, storm barricades, sack palaces, and put women and children to the sword. The more one reads, the more horrific the story becomes. The history of the Portuguese intrusion into the Indian Ocean is an epic of ruthless savagery.

Advertisement

How are we to explain the determination and the sheer cold-blooded cruelty of these Europeans who used their maritime expertise and the superior firepower of their guns to establish themselves on the coasts of West and East Africa, and erupted to such devastating effect into the Indian Ocean and the seas beyond? Much, but not all, of the answer is to be found in greed, from the lowest levels to the top. One after another of Crowley’s terrible accounts of the sacking of Asian cities tells of the Portuguese running wild after the assault and staggering away with as much booty as they could carry.

In a famous story that has been recounted a thousand times and is told again by Crowley, João Nunes, a converted Jew sent ashore by Vasco da Gama to discover the lay of the land after his ship anchored off the Indian coast, was taken by an astonished crowd to meet two Tunisian merchants who spoke some Castilian and Genoese. “The Devil take you! What brought you here?” they asked him. “We came,” replied Nunes, “in search of Christians and spices.”

Cinnamon, cloves, and pepper are integral to the story. Medieval Venice had exploited its geographical location as a bridge between Europe and Asia, and had grown rich on the proceeds of trade as it became the European emporium of spices, silks, and other Asian luxuries. Six years before Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India, Columbus’s landfall had created the possibility of a westward route that would give the subjects of the Spanish crown access to the riches of the East, and in so doing raised the stakes in any competition to break the Venetian monopoly.

Not unnaturally the relatively impoverished Portugal wanted a share of the action before it was too late. The establishment of a sea route running eastward by way of Africa to the Indian Ocean would undercut the mercantile republics of Venice and Genoa and, it was hoped, defeat the Castilians at their own game. It would also fill the coffers of the Portuguese crown, and could be expected to enrich nobles, fidalgos, and merchants who had already enjoyed some of the territorial and other benefits of overseas enterprise. These included sugar and other crops cultivated in the recently settled Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Canaries, and the Azores, and increasing quantities of gold and slaves flowing into Lisbon as a result of expanding trade relations with the societies living along the coast of West Africa.

The African slave trade in particular proved immensely valuable, not only to the crown, which enjoyed a fifth of the profit on revenues from the trade, but also to nobles who owned estates in southern Portugal and were faced with a serious labor shortage. From the mid-fifteenth century, seamen and merchants were shipping increasing numbers of West African slaves back to Portugal, where they were sold for estate labor and household service, as well as for the international market. As a result, Portugal acquired a rapidly expanding population of black slaves, who may have accounted for as many as 10 to 20 percent of the inhabitants of Lisbon by the middle of the sixteenth century.

But the Portuguese search was for “Christians” as well as for “spices.” European knowledge of the non-European world was still shadowy and confused, consisting of scraps of information or misinformation derived from the reports of merchants and friars who had traveled in Asia, along with a heavy dose of legend. Tales had long circulated of a land in Africa or farther east, perhaps in India, ruled by a Christian monarch, Prester John. These tales, given fresh currency in the fourteenth century by John Mandeville’s fanciful accounts of his travels, acquired new importance and urgency after Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and the Latin West felt its very survival threatened by the forces of Islam. If, however, Christians could locate and link up with the kingdom of Prester John, it might be possible to outflank the Ottoman Empire and attack it from the rear. When the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 this distant hope was transformed into a distinct possibility.

The prospect was made all the more compelling by the Iberian crusading tradition. The Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula had been forged in the long process of reconquering it from its Muslim invaders, and the Portuguese carried the crusade across the straits when they captured the Moroccan city of Ceuta in 1415. This was followed by what in effect was a permanent state of war in North Africa—a war of raids and counter-raids that offered opportunities to the nobility for booty, ransom money, and glorious victories in the best tradition of European chivalry.

Advertisement

The Iberian peninsula itself, however, was not freed from Moorish domination until 1492, when Granada, the last Moorish enclave on Iberian soil, surrendered to the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella. It was in the moment of euphoria created by the capture of Granada that Columbus, obsessed with the possibility of recovering Jerusalem, set out on his transatlantic voyage in the hope of reaching Cathay. But it was not only Columbus and the Spanish monarchs who dreamed millenarian dreams and were infused with messianic providentialism. Like his Spanish counterparts, Dom Manuel, king of Portugal from 1495 to 1521, saw himself and his kingdom as specially chosen by God to bring to a triumphant conclusion the crusade against the Moors.

At the start of his reign, however, counsels were divided about the future direction that the crusade should take. In reading Crowley’s book it is easy to forget that it was not India but Castile that remained the center of Dom Manuel’s attention, as growing uncertainty arose over the succession to Ferdinand and Isabella, and with it the distinct possibility that a carefully designed policy of dynastic marriages might one day secure the Spanish throne for his heirs. The desire to maintain good relations with the Spanish monarchs constituted a strong argument for supporting Castile’s plans to follow the Portuguese example and carry its own crusade into North Africa.

Members of Portugal’s four military-religious orders and of the Portuguese nobility favored further campaigning in North Africa, while also regarding raiding by corsairs in the Atlantic as a profitable sideline. The Indian Ocean, by contrast, seemed too remote for the kind of lucrative crusading warfare to which they were accustomed.

Others, however, and especially Portugal’s dynamic mercantile class, were primarily interested in the commercial possibilities of Africa and the East. Dom Manuel’s messianic providentialism, now reinforced by the dramatic success of da Gama’s mission, made possible some form of reconciliation between the competing viewpoints. With the riches of the East potentially at his command, and the way open for a pincer movement against the Ottoman Empire, it lay in his power to become both the master of the spice trade and the savior of Christendom. Trade and crusade could in this way be happily combined.

Da Gama’s mentality and approach fitted well with the requirements of the moment. Little is known of his early years, and it remains unclear why Dom Manuel should have chosen him for the Indian mission.4 As a younger son of minor nobility he may well have spent some time, like others of his rank, fighting in North Africa, which may have given him a hatred of Muslims that, as with Albuquerque after him, shaped and disfigured his career. As he moved up the East African coastline on his voyage to India he took it for granted that the Muslims he encountered were conspiring against him, and treated them with an undisguised belligerency.

Da Gama’s behavior would set a pattern that the captains of future Portuguese expeditions were to follow as they sailed into the Persian Gulf and through the Indian Ocean. Characteristically, on his homeward journey down the African coast, he gratuitously bombarded the Muslim port of Mogadishu to avenge real or imagined slights he had received on the Malabar coast. He thought its inhabitants, as Muslims, deserved nothing less.

More baffling in Portuguese eyes were the non-Muslims who inhabited Calicut in India. Da Gama and his companions were unaware of the existence of Hinduism, and assumed that these people were some form of deviant Christians, presumably the descendants of the converts made by the apostle Saint Thomas, who was thought to have carried the gospel into the subcontinent. Crowley is good on da Gama’s uneasy encounters with the ruler of Calicut, the samudri raja, “who was a Christian like himself,” and on the mutual misperceptions that clouded, although they did not destroy, their relationship. Misreading the Other was to be a constant in the unfolding story of European encounters with the non-European world.

Da Gama’s return to Lisbon was celebrated with pageantry and masses, and Dom Manuel showered him with honors. Equally, the news caused consternation in Venice and Castile. The king of Portugal had stolen a march on them, and would soon be flamboyantly styling himself “by the grace of God king of Portugal and of the Algarves of this sea and the sea beyond in Africa, lord of Guinea and of the conquest, navigation and commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India.”

He at once ordered the dispatch to India of a new, much larger fleet under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral, which on its outward voyage in May 1500 accidentally found itself off the coast of Brazil. When, under the terms of the authorization granted by the papacy to the monarchs of Spain and Portugal, he took formal possession of the new-found land in the name of Dom Manuel, Cabral unwittingly added to the Portuguese world a vast territory whose long-term importance was one day easily to eclipse that of their nascent empire in the East.

The Portuguese had no inkling of the tensions and rivalries generated by their sudden irruption into the trading community of the Indian Ocean, both among Muslim and non-Muslim merchants and among the rulers and cities along the Malabar coast. Cabral’s demeanor, at once arrogant and suspicious, on his arrival in Calicut some months later, soured his relations with the samudri raja, and ended in disaster. After he seized a ship in the harbor on the grounds that Muslim merchants were hampering the work of the Portuguese in loading their cargoes, a crowd attacked and massacred many of his men. His response was to order the capture of ten Arab ships and the slaughter of all those on board, and he then subjected Calicut to a day-long bombardment before sailing for home. In Crowley’s words, “The bombardment would never be forgiven. The massacre at the trading post demanded revenge. It was the first shot in a long war for the trade and faith of the Indian Ocean.”

When da Gama set sail in 1502 on his second voyage to India, both he and the peoples of the African port cities and the Indian Ocean knew what to expect. He would use any force that was needed to secure for the Portuguese the trading posts they wanted. It was on this voyage that he committed the most brutal and controversial act of his career, when he stopped a ship, the Miri, returning from the Red Sea with some 240 men, women, and children on board, many of them on their way back from a pilgrimage to Mecca. In spite of their acceding to his demand that they should hand over all their possessions, he went on to attack the vessel, eventually burning it, along with all its passengers and crew.

Da Gama returned home having established trading posts on the Malabar coast at Cannanore and Cochin. The challenge was now to gain control of the trade of the Indian Ocean and ensure a permanent Portuguese presence in the East, by securing through a mixture of negotiation and the deployment of military and naval power a string of fortified trading bases. These were to form the foundation for what seems to have been envisaged as a commercial and maritime, rather than a territorial, empire—an empire that would one day stretch all the way from Africa and the Persian Gulf to India, and then, by way of Ceylon, the Malay peninsula, and the Spice Islands, to the distant Chinese port of Macao. Known as the Estado da Índia—the state of India—its prime architects were Francisco de Almeida, from 1505 to 1509 the governor and first viceroy of Portuguese India, and his more decisive and dynamic successor, Afonso de Albuquerque, who in 1510 attacked and occupied Goa, the city that was to become the headquarters of this vast trading network.

With the help of contemporary sources Crowley gives us a striking account of the swath cut by Albuquerque through the lands and waters of the East. He seems to have been animated by a visceral hatred of Islam, perhaps as a consequence of ten years spent in Morocco, where atrocities were committed by both sides; the sacking of cities, the slaughter of their inhabitants, and the mutilation of prisoners were routine events there. He had also fought in a naval expedition launched from Naples against the Ottoman Turks, and in 1503 and 1504 served as joint commander of an expedition to India. Between 1506 and 1508 he brought devastation to the cities along the coast of Oman as he bullied and coerced them into submission to the Portuguese crown.

Albuquerque’s operations on the coast of East Africa and in the Persian Gulf in these years sharpened his strategic vision for Portugal’s future in the East. They also renewed the possibility of allying with what he believed was the Ethiopian kingdom of Prester John, if it could be found, and securing a permanent base on the Red Sea. From here the Christian forces could attack the formidable Mamluk empire in Egypt and then move on to seize Medina and recover the holy places of Jerusalem.5

Albuquerque’s career understandably gained him during his nine years in the Indian Ocean a lasting reputation as the terror of the East. In a revealing letter to Dom Manuel he wrote: “I tell you, sire, the one thing that’s most essential in India: if you want to be loved and feared here, you must take full revenge.” His terror tactics helped him establish Portugal’s Asian empire, although at a terrible cost.

The Indian Ocean had not exactly been a terror-free zone before the arrival of the Portuguese, but their amphibious operations, combining the long-distance deployment of their ships with the use of lethal gun-power both on land and sea, brought new levels of sophistication to warfare in the region.

Nonetheless the Portuguese suffered heavy casualties in their assaults on recalcitrant cities, and Albuquerque failed disastrously in 1513 before the walls of Aden when attempting to sever the Mamluks’ supply lines to the East. The Islamic world, even if divided within itself, was too extensive and too powerful to crumble beneath the attacks of a handful of Portuguese stretched out over vast areas.

In 1520, in an episode with which Crowley ends his book, a small Portuguese expedition to the Ethiopian highlands came face to face with its Christian ruler, whom they took for the fabled Prester John. Unfortunately this isolated figure was in no position to help them achieve Dom Manuel’s grand design for a combined attack on Islam, and the king died the following year with his crusading dreams unfulfilled.

What, then, was Portugal’s legacy to the wider world, beyond the fire and slaughter? Through their voyages Portuguese mariners had opened the way for growing numbers of Europeans—“hat men” as these strangely dressed foreigners were called in the East—to make their presence felt in Asia and Africa, and then to encircle the globe. Vasco da Gama and his successors laid the foundations of a worldwide empire, whose capital was Lisbon, “a relatively small and obscure capital on the periphery of Europe” transformed in the second half of the fifteenth century into “Renaissance Europe’s foremost global city.”

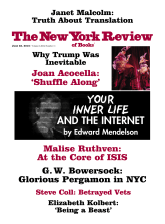

The words are those of the editors of The Global City, a superbly produced and illustrated volume of essays that examine different aspects of the other half of Crowley’s story—the impact, not of Portugal on the wider world, but of the wider world on Portugal, as seen on the streets and in the houses of Renaissance Lisbon. The inspiration for the book came from the recent discovery and identification of an oil painting done in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century by an anonymous Netherlandish artist of the Rua Nova dos Mercadores, the principal mercantile thoroughfare in Lisbon, running parallel to the waterfront, and obliterated in the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 (see below).

Society of Antiquaries, Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire

Anonymous Netherlandish artist: View of the Rua Nova dos Mercadores: Rua Nova dos Ferros with a Corner View of the Largo de Pelourinho Velho, circa 1570–1619. According to J.H. Elliott, this recently identified oil painting (the left half of which is shown here) depicts what was then the ‘principal mercantile thoroughfare in Lisbon’ and is a ‘rare representation of one of the great streets of Renaissance Europe.’

The provenance of the painting makes an exciting story in itself. It was bought from a London printseller in 1866 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in the belief that it was a Spanish work by an artist in the circle of Velázquez. He cut it in half, probably to make it fit more easily into the crowded interiors of his London residence, and then took the pieces with him when he moved three years later to Kelmscott Manor, in Oxfordshire, where the picture has remained.

The solution to the detective story of the origins of this rare representation of one of the great streets of Renaissance Europe has prompted a set of further detective stories as the editors and their colleagues investigate what lay behind the scene of a long arcaded street in which Lisbon’s multiethnic population goes about its business. The result is a volume of fifteen innovative essays that open many new windows onto the process of cross-cultural exchange in the first age of globalization. They tell us about the tastes of the inhabitants of the houses that lined the street, whether for ivories from West Africa, tortoiseshell caskets from Gujarat, porcelain and silks from Ming China, fans from Japan, or parrots from Brazil. They also tell us how native craftsmen in Africa and Asia responded to the enormous Portuguese and European demand for exotic products.

As The Global City so impressively demonstrates, the empire ruled from Lisbon began, and in many respects continued, as more of a commercial than a territorial empire, although in time its territorial aspects would come to the forefront, most obviously in Africa and Brazil. For a long time, however, it remained a scattered empire of garrisons and trading posts in which a handful of Portuguese merchants exchanged commodities with their local counterparts, while soldiers gave military assistance to rulers whom the Portuguese had secured as allies, and priests and friars sought with mixed success to instill into local populations the doctrines and practices of their Christian faith.

As an empire the Portuguese had its own distinctive characteristics, which to some extent would differentiate it from other European empires that followed it. Albuquerque, well aware of the shortage of Portuguese women and the high mortality rate among his compatriots in India, introduced a policy of racial intermarriage, although it remains unclear how much this was his own idea and how much he was acting under instructions from Lisbon. His marriage strategy would reinforce diplomatic efforts to secure alliances with local elites, while inducements to the rank and file to marry local women (mostly low-caste Hindus, but not Muslims) would in due course provide much-needed manpower for these undermanned outposts of empire. Its eventual effect would be to create a local Christianized population, and so to forge an authentically Indo-Portuguese society that would give the Estado da Índia a durability far beyond what might initially have been expected from the precarious character of Portugal’s toeholds around the Indian Ocean.

At the same time, alongside formal empire a kind of informal empire developed. Nominally, control of the empire was firmly centralized in Lisbon, but in practice logistical difficulties left the agents of empire with a high degree of autonomy, allowing them to establish virtual local fiefdoms, and in Africa to siphon into their own hands the slaves, gold, and ivory that properly formed part of the royal monopoly.

Meanwhile, many Portuguese who, for one reason or another, found themselves living isolated lives in these remote outposts of empire moved without authorization into their hinterlands. Here they became settlers, merchants, or mercenaries in the service of local rulers, carving out new and potentially more fulfilling lives for themselves in the process. Some would go native as they blended into local communities, at the very time when many natives were themselves becoming semi-Portuguese, as they were incorporated into the areas under Portuguese control, and adopted the religion, the customs, and the language of their rulers. In this way, Portugal’s overseas empire acquired the characteristics of a multinational and multicultural community, extending well beyond the formal boundaries of Portuguese-controlled territory.

2.

The opportunities for disappearance into the hinterland were especially strong in West and East Africa, where unauthorized Portuguese settlers and adventurers set up their own informal trading communities along the coast or moved inland, taking their language and customs with them. Along the coast of Atlantic Africa they operated around the edges of long-established kingdoms like Benin and Kongo, both of which Lisbon hoped to bring within its military and diplomatic orbit.

Benin proved impervious to attempts at conversion, but in 1491 the king of Kongo accepted baptism, and took the name of the Portuguese monarch of the time, João. His son, Afonso I, enthusiastically embraced Christianity, which he believed had allowed him to triumph over his brother, his rival for the throne. Under Afonso’s rule his kingdom became an ally of the Portuguese, who gave him valuable military help against his enemies.

He was careful, however, to prevent the Portuguese from inserting themselves too deeply into his kingdom and to keep the slave trade in his own hands. Still, strong cultural contacts were established between the two kingdoms. The members of the religious orders who came to Kongo brought with them not only Christianity but also literacy. The monarch, for his part, sent young men to Portugal to study the new faith, which he sought to integrate with the traditional belief systems of his own people, and he set up schools in rural regions of his kingdom to spread the new religion, or his own version of it.

The long-term result of the activities of Afonso I and his successors on the Kongolese throne was the development of a culture with distinctive Portuguese-African features that spread among the inhabitants of a region now covered by Angola, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The remarkable culture of the Kongolese kingdom from the time of the coming of the Portuguese to the twentieth century has recently been commemorated in a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. The lavishly illustrated catalog contains some illuminating essays, including a characteristically lucid account of the history of the kingdom of Kongo by John Thornton, who has done so much in his many publications to reconstruct an African past, for which written sources are all too often few or nonexistent.6

While bronzes from the Kingdom of Benin, in what is now southern Nigeria, are justly famed, the art of the kingdom of Kongo is much less familiar. This is partly explained by the survival of so few objects dating from the early period of encounter. Artifacts from Kongo were eagerly sought by Europeans, who valued them for their rarity and craftsmanship, and added them to the curiosities in their Kunstkammern. These included ivory hunting horns, or oliphants, of which examples could be seen in the exhibition, and textiles with elaborate geometric designs. Many of these artifacts, however, were lost over the course of the centuries, or—like so many later artworks from Kongo—disappeared into ethnographic collections where they aroused little interest and were often incorrectly identified.

Much of the Metropolitan’s exhibition was devoted to so-called “power figures” of both sexes, dating from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and notable for their forcefulness, their monumentality, and their power to shock. These figures, while drawing heavily on indigenous traditions and requiring for Western viewers a historical and geographical background that the exhibition sought to provide, also betray the effects of centuries of engagement between the societies of West Africa and the outer world. Insofar as this engagement began with the arrival of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century, the objects produced during the early stages of encounter hold a particular fascination as early examples of the reshaping of European images and models to bring them into line with native tastes and conventions.

As might be expected of these sixteenth- and seventeenth-century artifacts, several are inspired by, or closely associated with, the conversion of the kingdom of Kongo to the new religion. Of particular interest is a triple brass crucifix whose figures of Christ bear African facial characteristics, and a pendant of a tonsured Saint Anthony of Padua with a cross in his right hand and a Christ child in his left hand, poised on an open book (see below). These images are of more than African interest, in that they are emblematic of the global reach of Portuguese culture, and of the way in which it encouraged native craftsmen to create new objects and art forms that preserved their own traditions while simultaneously reflecting the new European influences.

Although no examples survive from Kongo, West African craftsmen used their technical skills to carve ivory figurative pieces of extraordinary virtuosity, some designed specifically for export to Europe. Portuguese Asia, too, saw the emergence of syncretic artifacts—caskets, ivories, and heavily decorated cabinets made of precious woods—made by both Portuguese and Asian craftsmen who responded inventively, like their African counterparts, to the challenge of devising a harmonious blend of indigenous and European styles and traditions.

Although Portugal’s overseas empire, whose origins are so vividly described in Crowley’s book, extended its range and influence in due course by successfully creating Indo-Portuguese and Afro-Portuguese communities and then holding them in its capacious embrace, it was too thinly spread and too undermanned to present more than a passing challenge to the Islamic civilization that Dom Manuel was so determined to overthrow. Crusade, in any event, was countered by jihad, and continuing conflict would bring no conclusion to the struggle that he and his subjects hoped would bring them perpetual renown.

That renown would come rather from their extraordinary success in navigating the oceans and imposing themselves on peoples of whom they knew nothing, and who knew nothing of them. In so doing they linked the world in a lasting network of commercial and cultural relationships, and left permanent traces of their presence in forms of language, faith, and artistic expression that emerged as a result of their intermingling with the peoples who became subjects of the Portuguese crown, or with whom they fought, traded, and cohabited.

Empire, however, was only achieved by deployment of a savagery and barbarism too easily overlooked. Camões may have sung the epic achievements of his compatriots, but it is Montaigne who should be allowed the last word:

So many goodly cities ransacked and razed; so many nations destroyed and made desolate; so infinite millions of harmless people of all sexes, states, and ages, massacred, ravaged, and put to the sword; and the richest, the fairest, and the best part of the world topsy-turvied, ruined, and defaced for the traffic of pearls and pepper.7

-

1

Luis Vaz de Camoens, The Lusiads, translated and edited by William C. Atkinson (Penguin, 1952). ↩

-

2

City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas (Faber and Faber, 2011); Empires of the Sea: The Siege of Malta, the Battle of Lepanto, and the Contest for the Center of the World (Random House, 2008); 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West (Hyperion, 2005). ↩

-

3

C.R. Boxer, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415–1825 (London: Hutchinson, 1969); Peter Russell, Prince Henry “the Navigator”: A Life (Yale University Press, 2001); Malyn Newitt, A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668 (Routledge, 2005); A.R. Disney, A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2009; two volumes). See also Portuguese Oceanic Expansion, 1400–1800, edited by Francisco Bethencourt and Diogo Ramada Curto (Cambridge University Press, 2007), for some excellent essays on different aspects of the Portuguese imperial enterprise. ↩

-

4

See Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama (Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 61–68, for da Gama’s background and an explanation of the king’s choice in terms of factional struggles in the royal court. ↩

-

5

See Albuquerque, Caesar of the East: Selected Texts by Afonso de Albuquerque and His Son, edited by T.F. Earle and John Villiers (Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1990), pp. 3 and 12, for his earlier career. ↩

-

6

See in particular his Africa and the Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge University Press, 1992; second edition, 1998). ↩

-

7

“Des Coches,” in The Essayes of Michael Lord of Montaigne, translated by John Florio (1603) (London: Dent, 1928), 3, p. 144. ↩