Black people in America have been under surveillance ever since the seventeenth century, when enslaved Africans were forced to labor in the tobacco and rice fields of the South. Colonial law quickly made a distinction between indentured servants and slaves, and in so doing invented whiteness in America. It may have been possible for a free African or mixed-race person to own slaves, but it was not possible for a European to be taken into slavery. The distinction helped to keep blacks and poor whites from seeking common cause.

The slave patrols that originated in the seventeenth century would be largely made up of poor whites—paterollers, the members of the patrols were called. To stop, harass, whip, injure, or kill black people was both their duty and their reward, their understanding of themselves as white people, something they shared with their social betters. Of course their real purpose was to monitor and suppress the capacity for slave rebellion. While the militias dealt with the Indians, the paterollers rode black people.

Police forces in the North may have been modeled on Sir Robert Peel’s plans for London, but as jobs connected to city politics, the policemen themselves, from Boston to Chicago, were Irish, people who had been despised when they first came to America. That they lived next to or with black people told them how close to the bottom of American society they were. In every city the Irish did battle with their nearest neighbors, black people, in order to become American and to keep blacks in their place, below them. North and South, the police were relied upon to maintain the status quo, to control a dark labor force that was feared.

White southerners during Reconstruction resented black police officers and their power to arrest a white man. Redemption, the triumph of white supremacy, pretty much eliminated black police officers. In W. Marvin Dulaney’s Black Police in America (1996), the story of blacks on American police forces until the 1970s is one of tokenism and distrust by white colleagues.

Meanwhile, police forces and their relation to black people in general is a long tale about the enforcement of whiteness and blackness. When in 1967 Carl Stokes, the newly elected black mayor of Cleveland who had won due to a coalition of black and white voters, assigned black police officers only, no white ones, to black districts of the city that had experienced riots, white police officials were indignant. What had the mayor taken from them?

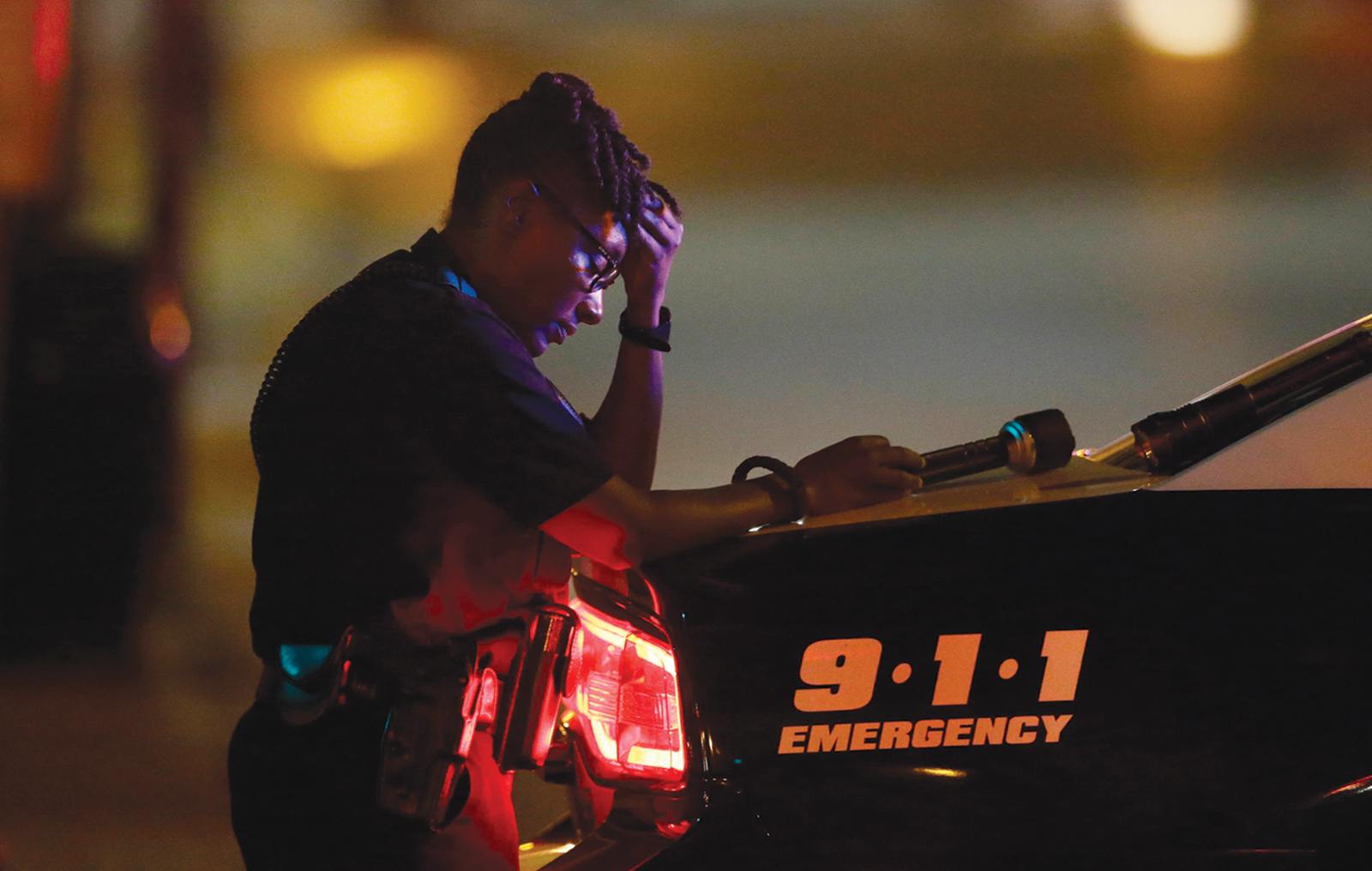

In the 1960s, the nation was told every summer to brace itself for a season of urban unrest, much of it, as remembered in essays in Police Brutality (2000), edited by Jill Nelson, ignited by confrontations between police officers and black people. There are the names of past victims of police killings that we have forgotten and there are names chilling to invoke: Eleanor Bumpurs, shot twice by police in New York City in 1984 because she was large and held a butter knife. But starting with Twitter keeping vigil over the body of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in the summer of 2014, and last summer, and already this summer, there is no more denying or forgetting. Social media have removed the filters that used to protect white America from what it didn’t want to see, thereby protecting the police as well. Instead of calling 911, black America now pulls out its smartphones, in order to document the actions of the death squads that dialing 911 can summon.

The camera has made all the difference. A camera can mean that there is no ambiguity about what happened. Feidin Santana just happened to be where he was with his cell phone when Walter Scott was killed in North Charleston, South Carolina, on April 4, 2015. We see Scott on the police car dash cam video getting out of that black Mercedes with the supposedly broken brake light and running. Then we see, on Santana’s video, Michael Slager firing eight shots into Scott’s back. We don’t see Scott trying to grab Slager’s taser, as Slager alleged.

In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 5 of this year, two cell phones captured two white policemen pinning Alton Sterling on the ground by a parked car in front of a convenience store. Footage from one cell phone is interrupted as one of the policemen yells “Gun” and several shots are heard. The woman filming from a nearby car has dropped down in her seat and she can be heard screaming. But the other cell phone, used by the owner of the convenience store, doesn’t blink. It records an officer removing something from Sterling’s pocket after he is dead. One of the things that will have to be determined is where his gun was before he was shot.

Advertisement

Brendon Jenkins, or “Jinx,” a cool-voiced black anchorman for the online news service Complex News, reported that in possessing a weapon, Sterling was in violation of his probation, given his record—and he offered this information, Jinx added, in the spirit of a transparency that he hoped the Baton Rouge police department would also show. The store owner, whose CCTV footage had been confiscated by the police, said that Sterling armed himself because street sellers of CDs, as he was, had been robbed recently in the neighborhood. Jinx also said that the two white police officers, Blane Salamoni, with four years on the force, and Howie Lake, with three years on the force, both put on paid administrative leave, were supposed to have said that they felt justified in the shooting. The officers said that the body cameras they were wearing fell off or were knocked out of order during the struggle.

On July 6, Diamond “Lavish” Reynolds went on Facebook moments after her fiancé, Philando Castile, was shot four or five times in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, outside St. Paul, and, with her four-year-old daughter in the back seat ready to console her, she became like a broadcast station from the car:

He was trying to get his ID out of his pocket, and he let the officer know that he was, he had a firearm, and was reaching for his wallet and the officer just shot him in his arm…. Please, Jesus, don’t tell me that he’s gone. Please, officer, don’t tell me that you just did this to him….

Philando Castile would turn out to have been pulled over by police fifty-two times in the past fourteen years, so he knew how to respond to a police stop. He also had over $6,000 outstanding in fines—the pressures of municipal revenue generation.

The Castile family was demanding that the police vehicle dash cam footage be released, as well as the name of the police officer—Jeronimo Yanez—(“Chinese,” Reynolds called him) who has been on the St. Anthony, Minnesota, police force for about four years. (Why does CNN correspondent Chris Cuomo address in public members of the Castile family older than he is by their first names? Young white people don’t always consider how disrespectful rather than friendly that can seem to older black people in his audience.)

In Reynolds’s broadcast on her Facebook page, the panic and unpreparedness are evident in the shrieking of Officer Yanez that can be overheard. He is still pointing his gun in the driver’s window as Castile, a popular school cafeteria supervisor, lies dying. He blames his victim. Reynolds knew instinctively what authority demanded and she repeatedly addressed the white man who had just ruined her life as “sir.” “You shot four bullets into him, sir.” After Reynolds has been taken from the car in handcuffs, her phone on the ground, Yanez can be heard shouting “Fuck!” Many of the killings in the past three years seem to have at their core the fury of these police officers that they have been defied by black men, that they have been challenged, not been obeyed.

Most police officers don’t want anything to go wrong, a retired New York City detective, a black officer, a former marine, explained to me last year on the anniversary of Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri. The first thing that happens, he said, is that they get taken off the streets, put on leave or put behind desks, and can’t make any overtime. Moreover, your colleagues don’t want to work with you because you’ve become a problem. Most officers do not in their entire careers use their weapons in the line of duty. When they do, what happens is not a matter of the training that was often some years ago and even then only for a few weeks. It is a matter of the individual officer’s character, what he or she is like in an emergency.

Until recently, grand juries were reluctant to indict police officers for shootings and when they did, trial juries tended to return dutiful not-guilty verdicts. Some black activists had hoped that white policemen going to jail for killing unarmed black men would act as a deterrent. In 2014, Officer Jason Blackwelder was convicted of manslaughter in the Conroe, Texas, death of Russell Rios, nineteen. Blackwelder was dismissed from the police force, because a felon can’t serve, but he was not imprisoned. He received a sentence of five years’ probation. There was no video of the crime he was tried for, but the forensic evidence—Rios had been shot in the back of his head—contradicted the policeman’s story.

Advertisement

Black Baltimore rioted following the death on April 19, 2015, of Freddie Gray, from spinal injuries sustained while in custody in a police van. Three of the six officers charged were white; three were black. One was acquitted of assault, reckless endangerment, and misconduct; a mistrial was declared in the manslaughter trial of another officer. Four are awaiting trial. In the video of his violent arrest, Gray is screaming and the man filming yells at the police for “tasering him like that.”

Officer Lisa Mearkle’s camera on her taser recorded the shooting death in Hummelstown, Pennsylvania, in 2015 of David Kassick, a white man, while he was down in the snow. Not every officer involved in police violence is male. She was acquitted.

In Chicago in 2014, the killing of Laquan McDonald, seventeen, captured on a squad car dash cam was so horrible that a court ordered the police to release the footage. The shooter is offscreen, but you can see puffs of smoke from some of the sixteen bullets striking McDonald and the street around him where he lies. After sixteen seconds, Officer Jason Van Dyke enters the frame and kicks away what is probably the knife that had been in McDonald’s hand. The case has been turned over to a special prosecutor. It is ironic that after so many years of hostility to the notion that we are under constant watch, not only do we accept cameras, we are in favor of the democratization of surveillance.

The police can be charged, yet the murder of black men, armed and unarmed, at police hands hasn’t stopped. Just as creepy people who want to mess with children try to get jobs that give them access to and authority over children, so, too, losers who want to throw their weight around and intimidate others with impunity are often drawn to a job like that of being a policeman. “The best way to deal with police misconduct is to prevent it by effective methods of personnel screening, training, and supervision,” the president’s Crime Commission Report recommended—in 1968.

Jurisdictions like Ferguson, Missouri, know who their trouble officers are. They accumulate histories of racial incident. They arrive as known quantities. It’s time to make it harder to become a police officer. The ones ill-suited for the job are burdens for the ones who are good at it. The videos of police killings also help explain those doubtful cases for which there are no accidental witnesses. The footage shows not only blood lust, state-sanctioned racism, or the culture of the lone gunman in many a police head, but also incompetence.

Nakia Jones, a mother and policewoman in Warrensville Heights, outside Cleveland, says in a moving Facebook post, “I wear blue,” telling other officers that if they are afraid of where they work, if they have a god complex, then they have no business trying to be the police in such neighborhoods. They need to take off the uniform:

If you’re white and you’re working in a black community and you’re racist, you need to be ashamed of yourself. You stood up there and took an oath. If this is not where you want to work at you need to take your behind somewhere else.

Officer Jones’s passion recalls Fannie Lou Hamer of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964. Jones also asked black men to put down their guns, to stop killing one another, and mentor young black males.

The camera has accelerated the decriminalization of the black image in American culture. The black men about to lose their lives in these videos don’t seem like threats or members of a criminal class; and we have been looking at and listening to President Obama every day. The Willie Horton ad isn’t coming back and those who try to use the old racist slanders as political weapons only make themselves into caricatures. The racist is an unattractive figure in American culture, which is why people go to such lengths to achieve racist goals by stealth.

Then, too, just as black identity is found to contain layers, so the majority of young whites might be embarrassed by a racial identity that bestows privileges the protection of which has become harmful to the general welfare. They want a fluid identity as well, a new kind of being white. To intimidate and imprison an urban black male population is unacceptable to them as the task of our police forces. Before Black Lives Matter, there was Occupy Wall Street, which, in Zucotti Park in downtown Manhattan, had a significant black presence, because of union participation alongside the integrated camps of students. The great demonstrations against the Iraq War had had no effect, and many went home, discouraged, for years. But the Occupy movement reopened the street as the platform from which marginal issues could be launched into mainstream consciousness.

The Washington Post reported in June 2015 that 385 people had been killed by the police in the first five months of that year, mostly armed men, a number of them mentally ill. The Post further reported that two thirds of the black and Hispanic victims were unarmed. A website, Mapping Police Violence, displays the photographs, stories, and legal disposition of the 102 cases during that five-month period in which the murdered were unarmed black people. Another site, The Counted, maintained by The Guardian, allows you to catch up by calendar day on the 569 people killed by police so far in 2016, and who they were.

Moreover, some urgent books in recent years have had considerable influence—works on racial profiling, stop and frisk, discriminatory sentencing practices, the disproportionately high black prison population, the profitability of the prison industry, the hallucinatory disaster of the war on drugs, and the double standard when it comes to race and class and the law. A quarter of the world’s prisoners are held in the US. Reform of the criminal justice system is a mainstream issue.

Political rhetoric of a certain kind—the absurd notion that protests against the police will lead somehow to higher crime rates—is predictably primitive and maybe some of the backlash we are hearing comes from frustration, the cry of a dying order. On the other hand, recent Pew Center research suggests that a wide discrepancy between black and white respondents is still there when it comes to support of police. Work slowdowns, the displays of tribal solidarity at police funerals—the police can come off as bullies who really mind being criticized, except that they have lethal weapons, the right to use deadly force. Police killings ought to be examined as part of the larger social menace of having too many guns around and far too many people who like guns.

Police practice has led to the violation of the Fourth Amendment and First Amendment rights of black people, but for black people a Second Amendment literalism invites persecution. In 1966, the sight of black men with rifles on the steps of the California capitol incited the state police and the FBI, and the destruction of the Black Panthers was assured. The black men in Dallas who came to the Black Lives Matter march on July 7 in camouflage uniforms, with their long guns, were risking their lives and maybe the lives of those around them. You think you’re a symbol, but you’re a target. When the shooting started, they ran like everyone else, and sightings of various black men with guns at first led the police to think that there was more than one gunman and that they were being fired upon from a tall building, not from inside a garage.

Brent Thompson, Patrick Zamarripa, Michael Krol, Michael Smith, and Lorne Ahrens were not the white police officers who killed Alton Sterling or Philando Castile; but the killer of these five white policemen, Micah Johnson, a black man, assumed that they could have been, they and the seven other officers he wounded at that Black Lives Matter march in Dallas on July 7. Or he decided that they had to pay for the deaths anyway. He is the disgraced ex-soldier with a grievance, the suicidal opportunist. It is distasteful to reduce deaths to the level of strategy, but Micah Johnson gave some right-wing opponents of Black Lives Matter the chance to pretend that parity exists between black men and white policemen as potential victims of racial violence.

The Dallas police chief, David O. Brown, a black man, the father of a son who killed a policeman and was killed in the ensuing shootout with police, explained at a press conference that Johnson had said he wanted to kill white officers. In fact some white officers protected black marchers from him.

Some young black people say they can understand being fed up enough to pick up a gun. In “16 Shots,” his response to the police killing of Laquan McDonald in Chicago, the rapper Vic Mensa warns:

Ain’t no fun when the rabbit got the gun

When I cock back police better run….

But we do not need agents of violent retribution.

The protests go on, without interruption. The response of Black Lives Matter to the Dallas killings was crucial and heartbreaking: “This is a tragedy—both for those who have been impacted by yesterday’s attack and for our democracy.” Dignity, not death.

This Issue

August 18, 2016

Fences: A Brexit Diary

The Mystery of Bosch