Every American decade since at least the 1920s is eventually reduced to a handful of images—photographs, news headlines, movie stills, cartoons, posters—that become the clichés of their time. For New York City of the 1970s, the images include weary and hemmed-in subway riders on a train every inch of which has been sprayed with graffiti; an aerial view of acres of burned-out apartment buildings in the South Bronx; curbside garbage piled like sandbags along a war trench during a sanitation workers’ strike; hordes of young men, beer bottles held joyously aloft, overflowing from the leather bars under the old elevated West Side Highway; a drab photograph of the punk music club CBGB on the Bowery; and the Daily News headline of October 30, 1975: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD,” with the subheading “Vows He’ll Veto Any Bail-Out.”

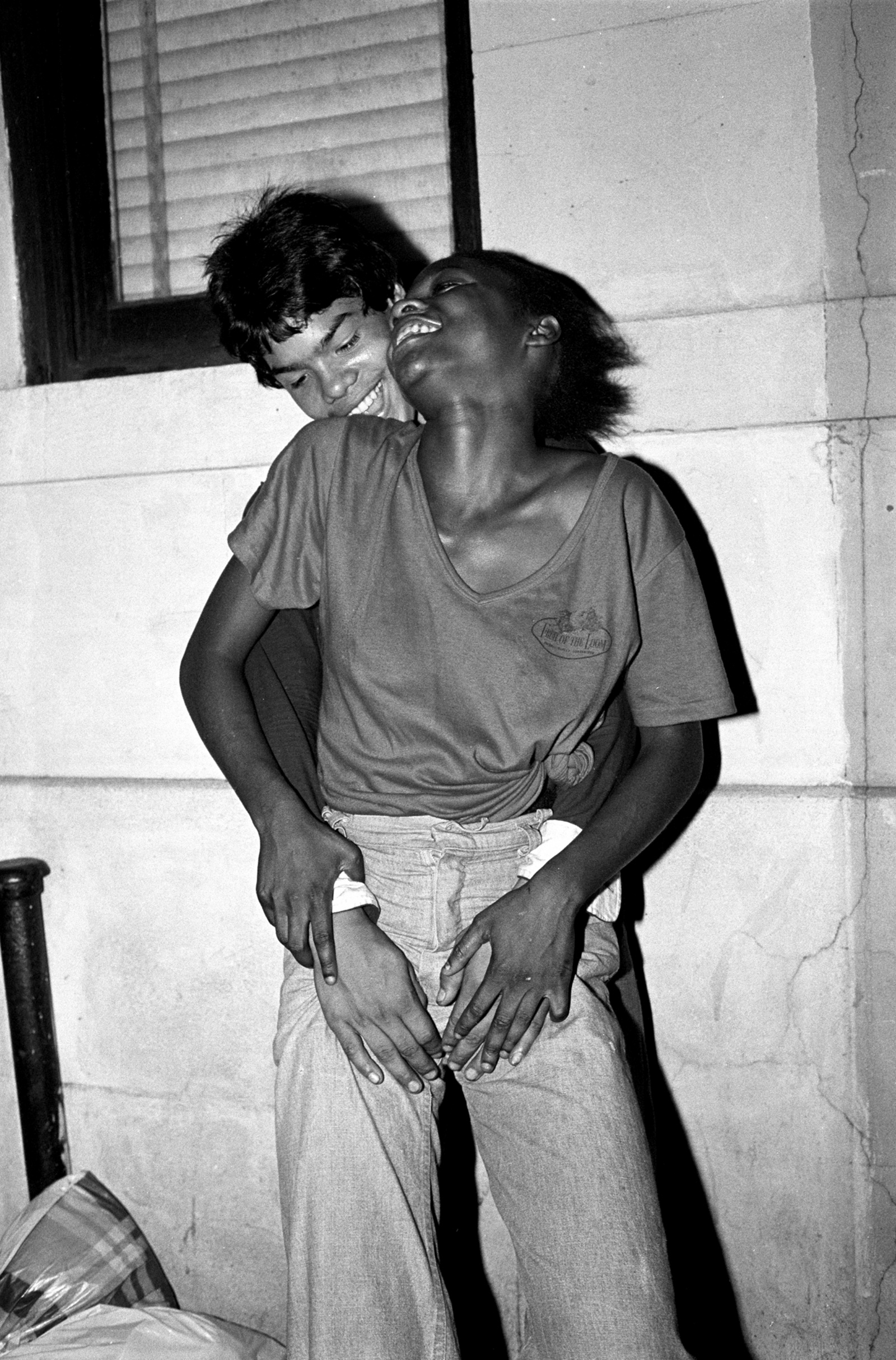

Most of these are images of despair, either because of what happened later (the decimation that would come with AIDS) or the advanced state of decomposition that beset New York at the time. Yet even then they carried a whiff of lawless glamour, and in recent years the 1970s have become New York’s most romanticized decade. Scorned by the rest of America (and by capital markets), the city was free to be its disinhibited self, its own raw glorious id that, the legend goes, constituted itself spontaneously out of urban grime.

In 1970, New York City’s population was 7,894,862. When the decade ended it had shrunk to 7,071,639, the lowest it had been since 1930 and the first and only decade in New York’s recorded history that it lost more inhabitants than it gained.1 1.75 million “Caucasians,” as the Census Bureau deemed them, left the city during the period, many of them moving to the Sunbelt after tax policy and rising energy costs encouraged the migration of jobs from the Northeast. Every other group increased: blacks by 116,000, the foreign-born by 233,000, Asians by about 137,000, and the census category known as “other or mixed race” by 678,000.

From this we might glean one version of what the city looked like in the 1970s: brown, queer, foreign, and so short of money that subway maintenance workers were obliged to rip spikes from one section of track to repair another. It was the antithesis of how much of America wished to see itself, yet a reflection of what many Americans feared the country might become.

“Drop Dead” of course was tabloid shock speech; President Ford never used those words. His avowed resistance to bailing out the city was meant to mollify New York haters in the hinterland. He and his advisers knew that, to use current parlance, New York was too big to fail without toppling credit markets nationwide. In 1975 the city had 300,000 municipal employees, a million welfare recipients, and a debt of $11 billion. Lenders threatened to cut off the flow of credit, which would have forced the city to shut down its subway system, its schools, its libraries, its basic daily operations. New Yorkers of the 1970s remember not only the sanitation strike, but transit workers and public school teachers walking off the job, highway workers blocking roads, drawbridges left open in protest, and police officers storming the Brooklyn Bridge, tilting some of the trapped cars and letting air out of their tires.

With Governor Hugh Carey’s support, Felix Rohatyn, a partner at the investment firm Lazard, was able to negotiate a restructuring of New York City’s debt. The deal called for extreme measures of austerity, and although it was far from equitable, virtually every civic sector sacrificed something, a level of cooperation that would seem to be almost unachievable today.2 The municipal unions agreed to a temporary wage freeze and the laying off of 20 percent of their members; creditors reduced interest rates on the restructured bonds; transit fares increased; taxes rose; and the city universities charged tuition for the first time in 120 years.

When credit markets balked for a second time, the unions stepped in to become, in effect, New York’s bankers, risking $3 billion in workers’ pension funds to buy Municipal Assistance Corporation bonds. By 1978, the city had managed to eliminate its short-term debt. Smart investors, in the meantime, made a killing buying up New York’s undervalued real estate at a discount.

The plot of Garth Risk Hallberg’s impressively meaty, high-calorie first novel, City on Fire, revolves in part around the opportunities that New York’s misery bred. The novel takes place, for the most part, in Manhattan and the Bronx between December 24, 1976, and July 13, 1977, the day Con Edison’s electrical grid overloaded during a heat wave and lightning storm, causing a blackout that lasted more than twenty-four hours. A cartoonishly evil character called the Demon Brother, a kind of Richard III figure who has wormed his way by marriage into effective control of one of New York’s most powerful investment banking houses, is laying plans to profit from the destruction, by fire, of the Mott Haven, Melrose, and Port Morris neighborhoods of the Bronx.

Advertisement

In spectacularly contrarian manner, the Demon Brother has broken ground for a series of glassy, upscale apartment towers called Liberty Heights in the borough’s most blighted zone. As an insider, he knows that New York will be financially rescued. The scorching of the South Bronx (97 percent of the buildings in some census tracts; the displacement of 300,000 Bronx residents overall) will accelerate the release of government money for his project as part of the inevitable effort to promote “renewal.”

An acutely disabling idea had entered the bloodstream of urban policy in those years: “planned shrinkage,” it was called, a term coined by Roger Starr, New York City housing and development commissioner under Mayor Abraham Beame. The idea was to curtail services in “unproductive” neighborhoods in order to demoralize residents and encourage them to move away. The more depopulated a neighborhood becomes, the less it merits the expense of full municipal services, and so the curtailment of services continues, following its own self-perpetuating logic. As an urban planner recently explained it to me:

You still pick up garbage, but instead of twice a week, you send the trucks around once every ten days. Buses that ran every eight to fifteen minutes now run every hour. You close the local public school, so students have to travel to get to class. Residents just get fed up.

After enough residents had moved away, the reasoning went, the neighborhood could be developed to reattract that chimeric white knight the “middle class” to come back and restore New York’s glory. This was planning that ignored the actual city and its living human potential in favor of what planners wished the city to be; residents are punished because they are not the residents officials desire. The 1.75 million white people who forswore New York in the 1970s had no intention of returning and it is doubtful that any realistic policy could have enticed them to think differently. There were a myriad of reasons for this, of course, chief among them the fact that private developers were unwilling to invest in middle-class housing in New York unless the government guaranteed them a profit with mortgage subsidies and other incentives. (The New York State Mitchell-Lama housing program for middle-income tenants, for example, assures the developer a profit of 7.5 percent a year, no matter what.)

In the South Bronx of the 1970s, planned shrinkage reached a new level of absurdity when firehouses were closed because the population was decreasing as a result of fires. No matter that 90 percent of those fires, according to the mayor’s own task force, were the work of arsonists hired by landlords so they could collect insurance. Response times to fires grew longer, ensuring that the flames caused maximum damage. It was difficult not to conclude that at least some government officials were content to stand by while landlords hastened the process of slum clearance for them. Private insurance companies finally put an end to the devastation when they refused to continue to pay out claims. In the year before fire insurance ended, the Bronx lost 1,300 buildings; the following year, it lost twelve.

Hallberg doesn’t delve much into these matters, nor should he be expected to do so. City on Fire is a historical novel; its author was born in 1978, in Louisiana, grew up in North Carolina, and came to live in New York when he was in his mid-twenties. Like many historical novels it is written through the filter of the present. It addresses readers who, like Hallberg himself, imagine with a certain longing a time before the “tsunami of capital” was unleashed on the five boroughs, when there was an atmosphere of menace and one lived “on the swivel,” as a friend of mine used to say, head turning alertly from side to side, attuned to the street, in an animal state of caution and aliveness. We should be careful not to exaggerate the dangers of quotidian street life in the 1970s, but to cut yourself off with ear buds and a smartphone would have been considered unwise, even if the technology to do so had existed.

One feels the hand of the present in several aspects of City on Fire. It goes without saying that New York in 1977 was almost the diametric opposite of New York in 2016. Far from having to lure middle-income residents, planners now struggle to keep them from being entirely priced out of the city. Private investors anxiously compete to build luxury housing in areas that until recently were among the city’s most neglected. The enshrinement of New York as one of a handful of global cities favored by the super-rich has turned large precincts into latter-day versions of Roger Starr’s “productive” fantasy. But it would take forty years for the demand for upscale housing to reach the point where investors would even conceive of a project like the Demon Brother’s in the neighborhoods of Mott Haven or Melrose. In 2010, according to the Census Bureau, the Sixteenth Congressional District, which encompasses the South Bronx, was the poorest in the nation.

Advertisement

I counted eight major characters in City on Fire, but the novel’s guiding spirit belongs to William Hamilton-Sweeney III, heir to what we are given to believe is the most prominent investment bank in New York. In the one (or in this case zero) degree of separation that marks almost every relationship in this story, it is William’s family bank that the Demon Brother has purloined. William’s father has taken the Demon Brother’s sister as his late-life bride. After meeting his replacement mother for the first time at the Hamilton-Sweeney Sutton Place townhouse, William drops out of boarding school, flees from his family, and doesn’t return to it for 800 pages.

William is delicate of body, handsome, gay, supremely serious, and so tormented by his emotionally distant father that he believes that “were he ever to give [him] an honest accounting of his feelings, the world would spontaneously combust.” Until that accounting is delivered and a true reckoning takes place, William will find no ease. In fact, his father is weak, not passionless, and far from indifferent about his son. His undemonstrativeness is merely the expected behavior of a certain sort of fictional WASP. In order to break the grip of three generations of Hamilton-Sweeney men who have surrendered their true selves to the icy duty of preserving the family fortune (William’s father had wanted to be a playwright), William must cut himself completely free.

Hallberg reverentially puts him through his paces as he wanders, in psychological exile, across the desert of 1970s New York. William’s first success is as songwriter and frontman for a seminal punk band called Ex Post Facto. The band recorded only one album, in 1974, but that album is punk music’s most “valuable document.” Patti Smith, Joey Ramone, and Lou Reed are this novel’s “intercessory saints,” but Billy Three-Sticks, as William is known in the punk world, hovers above them, more mysterious, more elusive, more “nakedly vulnerable.” One of Billy Three-Sticks’s songs supplies the novel’s title: “City on fire, city on fire/One is a gas, two is a match/and we too are a city on fire.”

Adding to William’s mystique is the fact that he has quit Ex Post Facto without a qualm, indifferent to his growing fame. His musical career was, in William’s own assessment, “a lark, a joke…just a way to blow off steam, to fuck with people’s heads.” William’s true ambition is to be a visual artist, but what he has produced so far “all looked reactionary, redundant, underwritten by the motions of a system too vast to comprehend, the way planetary spin inflects the movement of wastewater down a drain.” (This passage is fairly characteristic of Hallberg’s solemn metaphysical style.) William is presented as an exemplar of creative integrity, a pure art-for-art’s-sake soul.

During the course of his exile, William slums around New York, shoots himself up with heroin after heating crusted street snow in a spoon to dissolve the powder, and shoplifts expensive books from the Strand despite his trust fund (a tie to his family he has not broken). He is unable to feel worthy of his adoring lover, Mercer, an aspiring novelist who barely makes ends meet working as a teacher at a private Manhattan all-girl’s school. (Mercer, who is black, grew up in Georgia, where his family farms a modest plot of land.) When he stages an intervention to try to wean William from smack, William abandons him, as he had abandoned his family when his stepmother and her Demon Brother came crashing onto the scene.

Strung out, isolated, creatively blocked, William fills his studio with objects found on the street with the vague idea of concocting some form of supreme expression of New York. His breakthrough painting is

a stop-sign whose unique scumble of urban grit—whose peeling green pole, textured upon the canvas, whose reflection of morning light near a river in summer—made William want to cry. It was the stop-sign at the end of Sutton Place, which he’d last seen…on the morning he’d left home for good.

This leads to a series of other signs that are strategically displayed among real ones on the street—“the kind you saw on subway platforms, or taped to the bulletproof glass of bodegas.” The desired effect is for them to seem indistinguishable from the others, though they are slightly skewed (the Uncle Sam figure in a recruiting poster may be missing an eye) to alert you to the fact that they are not products of the real world but a comment on that world, meant to make you see it anew.

William’s more formal gallery paintings are, by contrast, “entirely white, albeit with surface disruptions that came clearer as you approached.” A reader may imagine a pastiche of minimalism and pop art, a melding of Robert Ryman’s rumpled, color-free canvases with Robert Rauschenberg’s found “combines,” inflected by the happenings that were a hallmark of the 1970s, where performance artists would infiltrate public spaces and the division between actual life and acted-out life was blurred.

Certain cities provoke a deep identification from their writers and artists, a kind of transubstantiation of self and place. One thinks of Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo, Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul, Saul Bellow’s Chicago, Joseph Roth’s Berlin, among many others. Borges, when he was in his early twenties, conceived of a long, open-ended poem that would encompass the entirety of Buenos Aires and establish its place among the great cities in the world’s imagination. (He abandoned the project, deeming it artistically impossible.) Hallberg attempts to turn William into this kind of artist-embodier of New York. His is a wish to be New York, to possess it because he is possessed by it. “Whatever happened to [New York] had to find its mirror in him,” Hallberg writes of William. He “wanted to reimagine New York.” It is as if he were “trying to re-create the face of the entire city.” A few other characters are also converts to the religion of New York. A young woman who has come to Manhattan from the San Fernando Valley feels “waves crashing down on the change she has tried to be, in the city she has longed to become.”

In William’s case, this idealized embrace of the total urban organism seems at odds with his guarded, somewhat self-obsessed experience of the world. Just as notable is how much he misses during his peregrinations. Though he has a studio in the South Bronx, he is barely aware of the tragedy engulfing the neighborhood, much less the emergence there of rap, the other musical phenomenon (with punk) of the 1970s. Whatever one may think of the commercial pervasiveness of hip-hop culture that came later, in its early incarnation rap was an enraged, realist, up-from-the-rubble report of ghetto existence.

In any event, readers may find it a stretch to believe that the son of an old-money billionaire from Manhattan’s cloistered suites of power would be the personification of grassroots punk music and art culled from the urban garbage heap. Like Liberty Heights, the fictional luxury apartment towers rising from the ashes of the South Bronx, William feels more like a representative of twenty-first-century New York.

William’s other nemesis, along with the Demon Brother, is a pretender who calls himself Nicky Chaos. Though he is completely devoid of musical talent, Nicky hangs around Ex Post Facto until he is made a member of the band. When William stops caring about it, he takes control. His father is half-Guatemalan, his mother speaks only Greek. He likes to show off his rather un-punk “superhero physique,” wears a muscle-tee that reads “Please Kill Me,” is heavily tattooed, and possesses “a resonant baritone” voice. He wants to be what William is: a creature-of-the-zeitgeist rock star and visual artist. But in the withering verdict of William’s effete gallerist, whom Nicky has approached with his work, “For him, kulturkritik is moustaches drawn on ladies in your Sears catalogue. He thinks a safety pin is jewelry. He confuses brutality with beauty.”

Nicky’s true calling is that of an amphetamine- and cocaine-devouring revolutionary extremist. Armed with a cursory reading of Nietzsche, Bakunin, and Marx, he presides over stoned seminars on politics and the danger of paying excess attention to the self. The seminars take place in an East Village squat where dozens of floaters stop by for the rhetoric and drugs. But Nicky’s actual followers can be counted on one hand.

They call the squat they live in the Phalanstery, a homage, one has to assume, to the early-nineteenth-century utopian socialist Charles Fourier, who advocated the establishment of what he called phalanstères, communities of common property with a cooperative division of labor designed to eliminate poverty. Nicky is no utopian, however, but a small-time megalomaniac in the mold of any number of cult leaders from Charles Manson to Andreas Baader of the Baader-Meinhof gang in West Germany. His theoretical trappings are those of a garden-variety nihilist whose “idea of changing the world,” in the assessment of a young woman who frequents the Phalanstery and is sleeping with Nicky, “is just to say no to everything.” In addition, he is susceptible to numerology, mystical New Testament passages, and other prophesies that confirm his belief in imminent destruction.

In a speech that reads as if it came straight from a potted television documentary about the period, he explains, “This is the ’70s now, the death trip, the destruction trip, the internal contradictions rumbling and grumbling, the return of the repressed…. You make things better, people relax. You make them worse, they revolt.” He dismisses what he calls “liberal humanism” because, by working within the system, liberals shore up the very system they supposedly want to change. “We are Post-Humanists,” says Nicky. “The Post-Humanist Phalanx. We redeem the claim of disorder on the system. And we’re just getting started. You dig?”

Nicky enters into a pact with the Demon Brother. In exchange for regular payments that are slipped by a courier under the Phalanstery’s door, Nicky and his crew toss firebombs into buildings in the South Bronx. Nicky sees this as a way to exacerbate the conditions of misery that he believes will incite the dispossessed to overthrow the established order. The Demon Brother, in turn, is making use of Nicky’s apocalyptic fervor to destroy so that the lucrative business of urban renewal can more quickly get underway. Hallberg’s joke is that these putative enemies work in tandem. William, for his part, is hunted by both sides.

A large cast populates Hallberg’s 911-page novel and he adeptly employs what has become the standard narrative technique of occupying the mind of each character in alternating scenes so that several intersecting stories can be simultaneously told. But City on Fire is weighed down by the exhaustive backstories that Hallberg loads onto his creations. This automatic flight into childhood, upbringing, adolescence, and to a series of curated events that are meant to serve as the ultimate explicators of his characters’ actions accounts for much of the novel’s length. In most cases, it forecloses any possibility the reader may have had of pondering the mystery of a character’s consciousness on his own.

Hallberg aims to enter the minds of his characters and then inadvertently bars the way inside. Jenny, a Vietnamese-American who works for William’s gallerist, for example, is a complicated, autonomous creation in the present time of the novel. But she is transformed into the equivalent of a nondescript face in a group photograph when Hallberg runs his rote background check on her life growing up in suburban California. And Mercer, William’s large-hearted lover, dwindles when Hallberg leads us on a sober and unsurprising march through his formative years in rural Georgia.

Hallberg may be describing his own dilemma when Mercer ruminates on his novel-in-progress:

In his head, the book kept growing and growing in length and complexity, almost as if it had taken on the burden of supplanting real life, rather than evoking it. But how was it possible for a book to be as big as life? Such a book would have to allocate 30-odd pages for each hour spent living (because this was how much Mercer could read in an hour, before the marijuana)—which was like 800 pages a day. Times 365….

City on Fire manages to capture some of the dark currents that ran through New York in the 1970s. It gamely attempts to link the devastation of the South Bronx to high finance and the real estate boom that eventually transfigured the city. But it too often reads as if James Michener, the late creator of best-selling historical sagas such as Hawaii, Texas, and Tales of the South Pacific, had set out to write a novel in the mode of Don DeLillo. It isn’t sure what it wants to be.

-

1

By comparison, in July 2015 the city’s population stood at 8.55 million. With new zoning regulations designed to promote dramatically denser development in large parts of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, it is expected to reach nine million by 2025 or sooner. ↩

-

2

See Felix G. Rohatyn, “The Coming Emergency and What Can be Done About It,” The New York Review, December 4, 1980. ↩