1.

Emma Cline’s best-selling historical novel The Girls is set in 1969, when a group of followers of the hippie Svengali Charles Manson, mostly young women, invaded the home of Sharon Tate, the actress wife of film director Roman Polanski. No one will have forgotten the massacre of the pregnant Tate and several friends, and the next night, of a couple in their suburban Los Angeles ranch house. Cline has changed the names, and relocated the Manson farm and the scene of the murders from Southern California to the small, arty, rural California community of Petaluma in the farm belt of Northern California, and mostly spares us grisly details. Her object is not to revisit Manson but to illumine the lives of adolescent girls, incidentally portraying some things about California that haven’t changed since then.

The novel is mostly told from the point of view of fourteen-year-old Evie Boyd, a nice, inexperienced, upper-middle-class California adolescent, during the summer before she’s to go off to boarding school. “I was an average girl, and that was the biggest disappointment of all” to her well-meaning parents. Divorced and distracted, they more or less don’t notice that she has drifted into the company of some very bad kids. Evie lies to her mother that she’s spending a lot of time with her tame friend Connie, but she has really been taken up by some strange girls she’s met in the park, and it’s their acceptance that she yearns for.

These girls, whom Evie sees as wonderfully liberated, live at a ramshackle ranch, and are in turn in thrall to an older, Manson-like figure named Russell, who controls them, has sex with them all, and makes them do the stealing and swindling for the bare-bones sustenance they share. Evie buys into the mythology of this scene, that Russell is a genius who will soon have a big recording contract, but it is his main girlfriend, Suzanne, to whom she is most drawn, enchanted by the older girl’s defiant freedom and self-confidence. As Evie sees it, Suzanne’s “face answered all its own questions,” whereas she sees her own face “blatant with need, like an orphan’s empty dish.” Cline has a lovely gift for the apt simile, and the book teems with startling description—one sometimes has a sense that some stern editor probably made her rein in her headlong gift for figures of speech, but the abundance that’s left is often wonderful.

Evie begins to spend more time at the ranch, riding her bike out there, hanging around, going along with the strange, druggy doings, simultaneously judgmental and drawn in. When she isn’t there, Suzanne seems to her “like a soldier’s hometown sweetheart, made gauzy and perfect by distance.” The well-managed but complicated chronology shifts between Evie’s fourteen-year-old perceptions and her older self looking back as a middle-aged woman staying in a friend’s house near a Northern California beach, working low-paying jobs as a nurse’s aide or spa attendant. She is haunted by a question she can’t answer: Would she have gone along with the things those lost, dangerous girls finally did? The older narrator, thinking about this, slightly sententiously muses:

There are those survivors of disasters whose accounts never begin with the tornado warning or the captain announcing engine failure, but always much earlier in the timeline: an insistence that they noticed a strange quality to the sunlight that morning or excessive static in their sheets.

Did she have those signals, that prescience? The adult Evie remembers how malleable she was as a girl:

My childhood visits to the family doctor were stressful events…. He’d ask me gentle questions: How was I feeling?… I’d just look at him with desperation. I needed to be told, that was the whole point of going to the doctor.

Cline captures the ambivalent adolescent state of mind that drives Evie to do things she knows are reckless or wrong, for instance invading the house of the Duttons, longtime family friends next door, at the instigation of Suzanne. Evie hastily diverts Suzanne from burgling her own house, claiming that her mother was “there all the time.” She remembers that “a part of me wanted [not to go through with this]. But another part wanted to fulfill the sick momentum in my chest.”

Evie and Suzanne are caught when Mrs. Dutton comes home early: “I see you, Evie Boyd.” And being seen is what girls most crave, which is one of Cline’s main points. The older Evie notes:

Suzanne and the other girls had stopped being able to make certain judgments, the unused muscle of their ego growing slack and useless…. They didn’t have very far to fall—I knew just being a girl in the world handicapped your ability to believe yourself.

The sick momentum propels Evie farther and farther into the bizarre world of Russell’s ranch. She scorns her normal life: Suzanne and the others had lived in a roofless salt factory in the Yucatan, while she, Evie, had only been “drinking the tepid, metallic water from my school’s drinking fountain.” Looking back to the Sixties,

Advertisement

as an adult, I wonder at the pure volume of time I wasted. The feast and famine we were taught to expect from the world, the countdowns in magazines that urged us to prepare thirty days in advance for the first day of school.

Day 28: Apply a face mask of avocado and honey.

Day 14: Test your makeup look in different lights….

A less accomplished writer might have chosen to portray Evie’s parents as neglectful monsters, but they are strangely sympathetic, or at least typical of their generation and milieu, for instance in their shock and confusion when she is caught during the house invasion. The older Evie remembers:

I could see how rattled she [her mother] was by this confusing new situation. Her daughter had never been a problem before, had always zipped along without resistance, as tidy and self-contained as those fish that clean their own tanks.

The tension, contempt, and affection between mother and daughter is perfectly captured: “My mother and Sal were drinking her woody tea from bowls, a new affectation my mother had picked up. ‘It’s European,’ she’d said defensively….” Evie watches her mother being fed a snow pea by a man she is dating: “The pity I felt for my mother in these situation was new and uncomfortable, but also I sensed that I deserved to carry it around—a grim and private responsibility, like a medical condition.” The adolescent’s hypercritical observations are painful for any parent to read: “My mother’s hair was growing out. She was wearing a new tank top with knit straps, and the skin of her shoulders was loose….” “I was embarrassed for my mother’s full skirt, which seemed outdated next to Tamar’s clothes…. Her neck getting blotchy with nerves.”

Despaired of by her baffled mom, Evie is sent to her father, who lives with Tamar, his former assistant, and, nonplussed by Evie’s delinquency, treats her with “the courtly politeness you’d extend to an aging parent.” Evie’s dawning understandings of her parents are one of the many pleasures of this book. She now can see her father as

a normal man. Like any other. That he worried what other people thought of him…. How he was still trying to teach himself French from a tape and I heard him repeating words to himself under his breath.

From her father’s, she runs away again to Russell’s ranch, where the scene is deteriorating, “the food situation getting dire, everything tinted with mild decay. They didn’t eat much protein, their brains motoring on simple carbohydrates and the occasional peanut-butter sandwich,” approaching the final catastrophe, when they work themselves up to avenge themselves on an agent they believe has cheated Russell. Evie narrowly misses being caught up in the murderous night, but she’s left wondering forever how far she would have gone. “Did I miss some sign? Some internal twinge?” For the reader it’s highly suspenseful; even though we know the real-world outcome, we don’t know what will happen to Evie.

The older Evie at some point is moved to explain to a younger friend about the Sixties California zeitgeist: “‘People were falling into that kind of thing all the time, back then,’ I said. ‘Scientology, the Process people, Empty-chair work. Is that still a thing?’” In middle age, her despair is private, cynical, and somehow still youthfully Californian:

Reading articles on the effects of soy on tumors. The importance of filling your plate with a rainbow. The usual wishful lies, tragic in their insufficiency. Did anyone really believe in them? As if the bright flash of your efforts could distract death from coming for you, keep the bull snorting harmlessly after the scarlet flag.

The most interesting thing about this well-written, sometimes overwritten, gripping novel is its sympathetic examination of the whole situation of an adolescent girl, her premonitions, her powerlessness and lack of direction, the inexorable power of conventional expectations shaping a future that—absent clear, imaginative direction—she is unlikely to be able to shape for herself:

Poor girls. The world fattens them on the promise of love. How badly they need it, and how little most of them will ever get. The treacled pop songs, the dresses described in the catalogs with words like “sunset” and “Paris.”

Looking at newsreels of the Manson arrests today, it’s hard to believe in those fresh, beautiful, young women as ruthless killers, and this is part of Cline’s point, the wish and need of girls for potency and agency in a world that consigns them to sexting and secretarial school.

Advertisement

2.

Emma Cline, the author, is herself twenty-seven years old, young enough to remember and evoke Evie’s teenage anomie, boredom, sexual detachment, her yearning for meaning and belonging. And maybe because she is close in age to her teenage protagonist, Cline can understand, without disapproving or patronizing, “the hidden world that adolescents inhabit, surfacing from time to time only when forced, training their parents to expect their absence.” The result is the kind of author–creation rapport we feel between, say, Holden Caulfield—whom Evie in some ways resembles—and his creator, or even Elizabeth Bennett and hers. How much attention should we, do we, pay to the age of the author?

Reading a book, we always dimly feel the author’s presence, a shadowy figure behind the characters and apart from them, to whom we can address silent objections if the end doesn’t satisfy or something seems off, a subliminal but real sense of the age, gender, and probably the nationality of that author, even if she never speaks to us or appears in the text. An older author may be venerable, but at a minimum inhabits a neutral space of authority in the manner of, say, Thackeray or Dr. Johnson.

It’s different if the author is younger than we are. Knowing that deprives the text of some authority—though it may impress with its prodigious talent, as here; instances of naiveté may impress us with their charm, and satisfyingly illustrate to us our superior age and knowledge, our more tempered or reasoned reactions. Here, Cline’s nearness in age to her subject works to great advantage, lending to the fourteen-year-old Evie freshness and credibility, while allowing her to step back sometimes into the life of the older Evie, the middle-aged woman staying in a friend’s house near a Northern California beach.

Cline, like her character Evie, is nonjudgmental, old enough to see the Boyd parents as regular, insensitive, bourgeois people with their own preoccupations, like most people, believing certain Sixties things about the harmlessness of drugs, the coming of the new dawn, political freedom, and so on. They inhabit a social category often satirized or treated as if it didn’t quite exist: comfortable, presumably WASP, suburban. And Cline is also young enough to capture with great freshness the thickness of Evie’s friend’s braces, or things about family tensions that get forgotten with time.

Hers is an entirely successful evocation of Sixties California, right down to the contents of the fridges, the clothes—“the hobby Satanists who wore more jewelry than a teenage girl. Scarab lockets and platinum daggers, red candles and organ music”—above all the mindset—the parents smoking dope with their kids, the apathetic adolescent sex—what it was like before Cline was born, which therefore she must only have researched. Did she find photos of the Berkeley girls along Telegraph Avenue, wearing red velvet frock coats in the August heat, whom she so vividly brings to life?

With all this meticulous description, The Girls is full of the pleasures of recognition for the Californians among her readers, and evocations of things unchanged from the Manson era. “I know the Clines,” someone said at a recent dinner party, “they have that vineyard.” “One of the Manson girls was in my high school,” says someone else. Some of my nieces went to Santa Catalina, probably the original of the boarding school Evie goes to; one of my daughters brought up her kids in Petaluma. In this it’s a very California novel; the thickly regional references remind us that though we might think of the New York novel, or the New England, or the Southern novel, when it comes to California writing, the shared qualities of its great exponents from Bret Harte to John Steinbeck, Raymond Chandler, Joan Didion, and many more, aren’t often treated as adding up to a literature; California is the Canada of American regionalism.

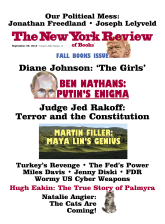

This Issue

September 29, 2016

Maya Lin’s Genius

The Heights of Charm

How They Wrestled with the New