In her interview for No Direction Home (2005), Martin Scorsese’s brilliant three- and-a-half-hour documentary about Bob Dylan, Joan Baez suggested there is something in Dylan’s music that goes “to the core of people”; there are those, she acknowledges, who are simply “not interested—but if you’re interested, he goes way, way deep.” Books on Dylan have been pouring from popular and academic presses for decades now, not to mention the numerous long-running fanzines that often combine recondite nuggets of information about Dylan performances or recording sessions (who was on bass on which take, what kind of hat he wore on stage) with scholarly accounts of sources for particular images or general appraisals of his musical and literary influences. Occasionally one learns about the more egregious of his many eccentricities. The sheer volume and variety of this secondary literature on Dylan is itself weighty testimony to the impact of his music on those who like it: it goes way, way deep, and provokes this need to explore Dylan’s effects, to analyze his compositional habits, to interpret the carnival of characters that he creates—including, of course, the overarching one of Minnesota-born Robert Zimmerman’s creation of Bob Dylan.

But explaining the magic of a song or performance is much harder than explaining the excellence of a poem or novel. There’s an uncomfortable scene, for Dylan fans, in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, in which the Allen character grimaces almost in pain as a rock journalist (played by Shelley Duvall) recalls a Dylan concert she has just been to, and then admiringly quotes the chorus of “Just Like a Woman.” Allen’s scorn at first makes you wonder how you would set about defending the lines, but that quickly comes to feel pointless. Sixties hipster language takes us much closer to what is perhaps the only question really worth asking about Dylan: Hey, do you dig what this cat’s up to—or are you some kind of square?

It was delightful to learn this October that the Nobel Prize Committee for Literature dug Dylan, although, it soon turned out, this didn’t mean that Dylan dug the Nobel Prize Committee for Literature. A message fleetingly appeared on his website acknowledging that he had won the prize, but that soon disappeared; the “wanted man” was nowhere to be found; he was, like the girl berated in “Like a Rolling Stone,” “invisible now.” Contrary to reports in the popular press, Dylan has given hundreds of interviews throughout his career—indeed there’s a whole book of them, called Dylan on Dylan (2006). But clearly he wasn’t eager to confront armies of journalists and mouth platitudes about being honored and grateful etc. His lyrics are full of drifters escaping, of on-the-road types heading for another joint, of outlaws singing outlaw blues; the chorus of one of his greatest songs succinctly expresses his horror of being pinned down and defined: “I’m not there…”

As was pointed out by a number of Dylan admirers in the aftermath of the Nobel announcement, the issue of whether or not what he does is “literature” is utterly tedious. What the award did, of course, prove is how much literary types dig his music, and wished, like practically all those who have ever written about him, to register this. Insiders suggest that he has been considered for the Nobel many times, and given the “reach and significance” (to adopt the bureaucratic terms used by institutions to measure cultural impact) of his work for over half a century, this is hardly surprising. His songs have infiltrated and shaped the sensibilities of so many of those who get consulted about the prize each year that he was bound to have become a serious candidate.

Would he accept it? He certainly played hard to get. Over two weeks elapsed before he finally came forward. Shyness or showmanship? Possibly, as so often with Dylan, both. Tongue firmly in cheek, he explained that news of the award had left him “speechless”; he teasingly promised to do his best to make it to the ceremony. We can, therefore, look forward to seeing how the author of “Masters of War,” a song bitterly denouncing the arms trade, deports himself when he arrives in Stockholm in December to accept a prize funded by a successful manufacturer of weapons. One wonders if there will be an outraged heckler there ready to shout out “Judas,” as so famously happened at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester in May 1966 toward the end of Dylan and the Band’s electric set.1 Unless he brings a five-piece combo with him, he won’t be able to respond as he did then—“I don’t believe you, you’re a l-i-i-ar—hit FUCKING LOUD.” The Band did indeed play as instructed, and Dylan delivered a sublimely vituperative performance of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Advertisement

Although Dylan fans make competing claims for different phases of his extraordinarily diverse career, there is broad agreement that what he achieved from 1965 through 1967 will never be surpassed, indeed could never be surpassed—either by Dylan or by any other rock musician. The recording sessions that resulted in the quartet of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde, and The Basement Tapes have a status for Dylan’s admirers akin to that of Shakespeare’s four major tragedies for Shakespeareans. In a rash moment of excitement while assessing the outtakes recently released as The Cutting Edge for one of the Dylan fanzines, I foolishly suggested that listening to the CD gathering all the outtakes of “Like a Rolling Stone” was a bit like watching Shakespeare write Hamlet—which was really just a hyperbolic way of saying that Dylan’s music of 1965–1966 in particular goes way, way deep. But in D.A. Pennebaker’s footage of Dylan’s on- and offstage self-performance during his tour of Australia and Europe in 1966 with the Band, which is liberally sampled by Scorsese in No Direction Home, there is undoubtedly an element of the Hamlet-like in the leading man’s antics and eloquence, in his wit, his charisma, his defiance, his ability to deliver great torrents of imagery and yet convey a sense of being unreachable and enigmatic.

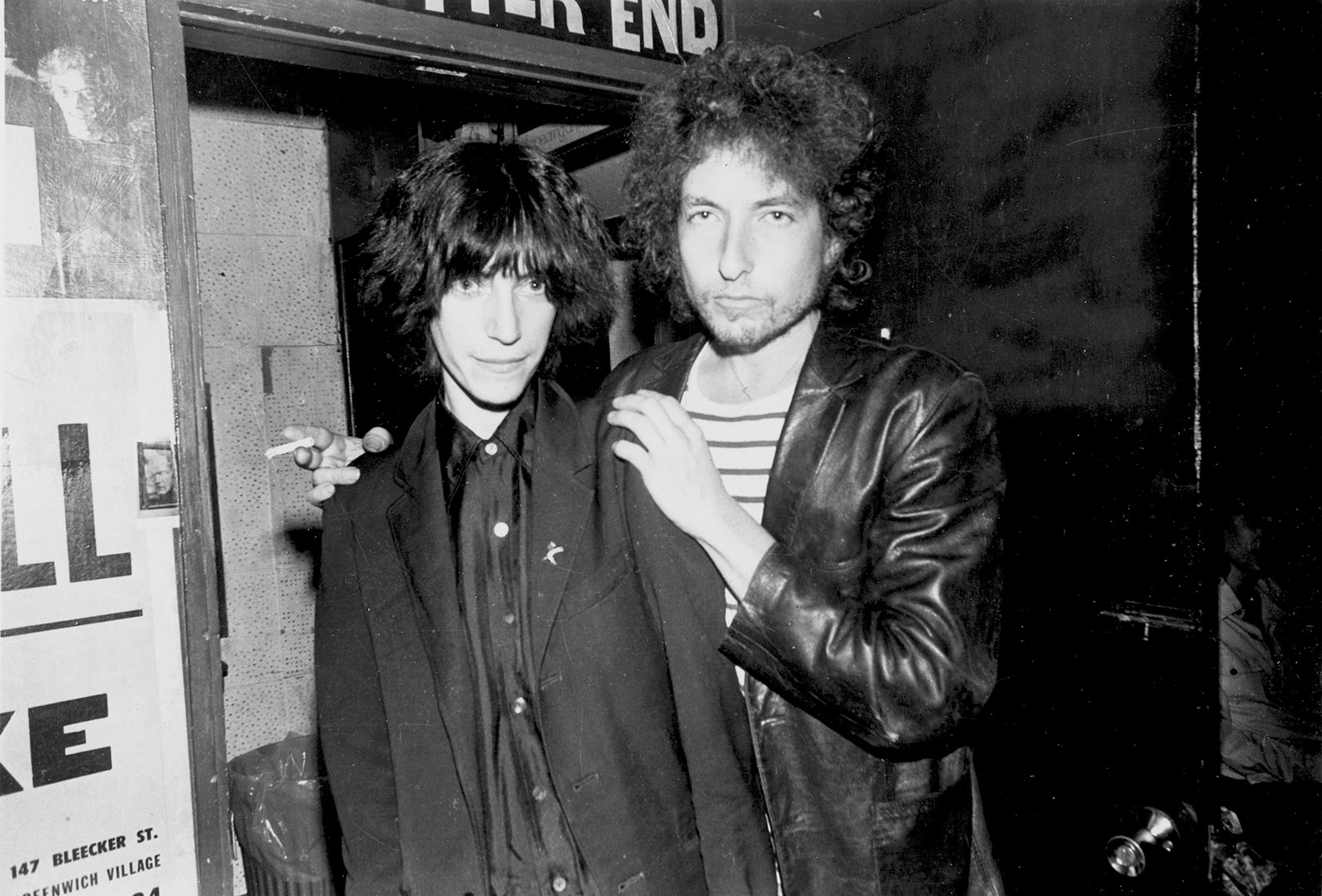

The Dylan of this tour was a wired and sophisticated dandy in a fancy checked suit, a Rimbaud-fueled iconoclast who believed in his music but possibly not much else. It was not easy for ardent lovers of folk to welcome this metamorphosis; it was Dylan’s “finger-pointin’” songs of explicit political protest that first catapulted him to fame soon after his arrival in Greenwich Village in January 1961. Early songs such as “Ballad of Hollis Brown” or “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” have the unerring directness and force of a Bertolt Brecht ballad—Brecht, like Rimbaud, is one of the literary influences openly acknowledged by Dylan. His astonishingly swift development in his early months in New York was so puzzling to those who’d clocked him as a run-of-the-mill folkie (a type wonderfully captured in the Coen brothers’ recent film Inside Llewyn Davis) that a rumor spread: Dylan, like his great hero Robert Johnson, had surely sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads for the gift of musical genius.

Other high points for most Dylan aficionados would include Blood on the Tracks (1975) and the subsequent Rolling Thunder Revue, although I personally think his finest post-1966 concerts were those of his evangelical period, between 1979 and 1981. And although dismissed by the music press has having definitely lost the plot countless times, Dylan has repeatedly confounded his critics’ attempts to write him off. Such is the nature of our man that on even the most ramshackle and uninspired night of the Never Ending Tour, which began in 1988, he is liable to scale the heights and recreate his “wild mercury sound” in the course of a rendition of, say, “Buffalo Skinners” or “Pretty Peggy-O.” The sessions for Infidels (1983) and Oh Mercy! (1989) resulted in many extraordinarily potent songs, although not all ended up on the albums in question. Even the rather pastiche-like Love and Theft (2001) has one song, “Mississippi,” that ranks with all but the greatest of Dylan’s earlier compositions.

In my own quest to explain why Dylan goes way, way deep with me, I wrote an essay some years back exploring overlaps in his work and persona with those developed in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson. I was drawn to this by Emerson’s description in his essay “The Poet” (1844) of the ideal American bard:

Stand there, baulked and dumb, stuttering and stammering, hissed and hooted, stand and strive, until, at last, rage draw out of thee that dream-power which every night shows thee is thine own; a power transcending all limit and privacy, and by virtue of which a man is the conductor of the whole river of electricity.

Surely this passage could be read as a rhapsodic, visionary, proleptic account of Dylan’s experiences in 1965 and 1966 when he took to the stage in the second half of each show (after an acoustic first half) with the Band and an electric guitar, and alchemically (and possibly chemically too) transformed himself into “the conductor of the whole river of electricity,” much to the jeering dismay of his folk following, who hissed and booed; it was a disgruntled folk music fan who shouted out “Judas” on the night of May 17 in Manchester. And it strikes me now that anyone baffled by Dylan’s refusal to reply immediately to the Nobel committee’s communications could do worse than read Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”:

Advertisement

Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist…. What I must do, is all that concerns me, not what the people think…. The great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude…. Do your thing, and I shall know you…. A man must consider what a blindman’s-buff is this game of conformity.

Almost every aphorism in this essay can be read as concordant with Dylan’s vision of the outlaw hero; or as he put it himself in one of his more Emersonian moments, “to live outside the law, you must be honest.”2

If pressed to make a case for the “literary” merit of Dylan’s songs, or at least to indicate some of the elements that make him such a great writer of song lyrics, I would probably start with his gift for the compressed narrative, his ability to hit off a scene or character with electric swiftness. This is present in even his earliest songs: “Hey, Mister Bartender,/I swear I’m not too young” (“Poor Boy Blues”). Does the underage boy get served by the bartender, and why does he need the drink? “Something happened to him that day/I thought I heard a stranger say./I hung my head and stole away” (“Ballad for a Friend”). What does the speaker overhear about his friend, and why does it make him hang his head and slink away?

One of Dylan’s most startling early innovations was to combine blues-style vignettes with folk’s more complex narrative traditions. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” for instance, while it doesn’t exactly tell a story, amalgamates a series of mini-anecdotes into a kaleidoscopic catalog that manages to be responsive both to its moment of composition (the late summer of 1962—i.e., cold war tensions that would lead to the Cuban Missile Crisis, violently repressed civil rights marches, etc.) and to its origins in the centuries-old traditions of the oral ballad—it derives its chorus and structure from the Anglo-Scottish Child ballad “Lord Randall”:

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world… I met a young woman whose body was burning… Where black is the color, where none is the number…

Not all the song’s vignettes, however, have a clear moral value: “I saw a white ladder all covered with water”; “Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’.” Some verge on the sentimental: “I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow.” While the general drift of the song is clear, and Dylan unashamedly figures himself in the final verse as a wandering minstrel ready to stand up for the underdog and deliver the truth as he sees it, not all its mini-narratives chime with this perspective. Some pull in quite different directions, as if Dylan were already reacting against the looming demand that he subdue his imagination in order to adopt the role of political spokesperson for his followers. In his autobiography Chronicles (2004), Dylan returns over and over to his fear of being trapped and typecast as “the voice of his generation.”

The collage technique deployed in “Hard Rain” soon developed into one of Dylan’s most effective ways of putting together a song. It enabled him not only to provide a series of roving snapshots of a milieu, but to explore it both from within and from without. Consider the opening verses of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965):

Johnny’s in the basement

Mixing up the medicine

I’m on the pavement

Thinking about the government

The man in the trench coat

Badge out, laid off

Says he’s got a bad cough

Wants to get it paid off…Maggie comes fleet foot

Face full of black soot

Talkin’ that the heat put

Plants in the bed but

The phone’s tapped anyway

Maggie says that many say

They must bust in early May

Orders from the DA…

This updates Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business” by fusing it with Allen Ginsberg’s vision in “Howl” of an elect band of countercultural transgressives. We are inducted vividly into the world of mid-1960s Lower East Side bohemia—its paranoia, its sense of election, its zany humor, its argot (“medicine” for drugs, “heat” for police, “plants” for listening devices), its arresting cast of characters bonded, if only transiently, by their decision to live outside the law. But whereas Ginsberg celebrates, in Whitmanian fashion, the antics of his heroic band of Beats, Dylan is more poised and neutral, and certainly too hip to believe in the utopian politics underlying Ginsberg’s excited strophes. The song’s glamour and excitement derive not from the modus vivendi of those who drop out and join the underground, but from the wit and compression with which the scene’s chronicler hits off the milieu, even parodying its mantra: “Don’t follow leaders/Watch the parkin’ meters.” While Beat-style surrealism was undoubtedly a liberating catalyst for Dylan’s imagination, it also became one of his most lethal means of putting down the other cats on the scene:

You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat

Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat

Ain’t it hard when you discover that

He really wasn’t where it’s at

After he took from you everything he could steal…

(“Like a Rolling Stone”)

It has long been bruited that this is Dylan’s take on the relationship between Edie Sedgwick and Andy Warhol. Whatever the source of these lines, their effect is to establish that it is Dylan himself who is “where it’s at”; that he, to borrow a phrase from W.B. Yeats, is “the king of the cats.”

If it is the literariness of Dylan’s lyrics that has in part led to their being more discussed than those of any other comparable songwriter, it is not their literariness that makes them good. His most literary song, “Desolation Row” (1965), with its references to Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot fighting in the captain’s tower, is eminently discutable, but one doesn’t often feel like listening to it. I think the Nobel Prize Committee was right to link Dylan’s achievement to “the great American song tradition”; for his spongelike absorption and adaptation of so many different elements of American song is a key factor in the length and excellence of his songwriting career. (His debt, incidentally, to both famous and obscure was amply repaid in his Theme Time Radio series, which also threw a fascinating light on his early musical tastes and the astonishing range of his knowledge.)

It was the great American song tradition that allowed Dylan both to discover and to escape himself; and his own songs have, in turn, allowed those who dig them to discover and escape themselves. Dylan may—or may not—disdain the honor of being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, but to Bobcats around the world it proved a welcome validation of their experience of his music, of its power to go way, way deep.

-

1

Bizarrely, nearly forty years later two different people (Keith Butler and John Cordwell) put forward competing claims to have been this infamous heckler. Both are now dead. Cordwell seems to me the more convincing candidate. ↩

-

2

My essay, “Trust Yourself: Emerson and Dylan,” was published in Do You, Mr Jones? Bob Dylan with the Poets and Professors, edited by Neil Corcoran (London: Chatto and Windus, 2002). On the subject of Dylan among the professors, the most rewarding and intelligent academic book so far written is, in my opinion, John Hughes’s Invisible Now: Bob Dylan in the 1960s (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013). ↩