I have often wondered why nineteenth-century French novelists were quite literally obsessed with painters and painting, while in the 1700s Diderot was the only writer of his generation to take an interest in art criticism. What a striking contrast: not one major novelist of the 1800s failed to include a painter character in his work. This is not surprising for Balzac and Zola, who had ambitions to bring every aspect of society to life in their fiction; but read Stendhal, Flaubert, the Goncourt brothers, Anatole France, Huysmans, Maupassant, Mirbeau, and of course Proust, and you enter a world in which painting is surprisingly important. What is more, all these novelists explored not only how a painter sees things but also how he represents them, and this produced a new way of writing.

“I would only have liked to see you take apart the mechanism of my eye. I enlarge, to be sure; but I don’t enlarge like Balzac, any more than Balzac enlarges like Hugo,” Zola told his protégé Henry Céard, highlighting the visual nature of novels at the time. This was essentially a French phenomenon; it has no real equivalent in England, Germany, or Russia. In the United States, it was not until the end of the century that painting became a literary subject in the work of Henry James. In England, Virginia Woolf would be the first to write about the influence painting had on literature. Why the sudden, widespread interest in France?

I believe that this new way of seeing and writing was facilitated by the creation of museums in France after the French Revolution. Frequent long visits to the Louvre gave an entire cohort of young writers a genuine knowledge of painting, a shared language with their painter friends, and a desire to enrich their own works with this newly acquired erudition. The visual novel dates from this period.

Having easy access to great works by visiting a museum feels so obvious to us now that we rarely think of the cultural revolution brought about by the advent of modern museums. And yet what a sea change in behavior this opportunity afforded. Before the Revolution only birthright or unusual personal success opened the door to masterpieces held in palaces and mansions, or to galleries of fine paintings acquired by wealthy Parisian collectors. As a result, people were reduced to spending a great deal of time in churches, the only place where anyone was free to admire works of art, at least before or after mass. Italy was especially well endowed in this respect.

But appreciating a painting in the gloom of a chapel posed problems that would continue for a long time: during a visit to Venice, Henry James complained he had to forgo admiring the magnificent work of Cima da Conegliano in the church of San Giovanni in Bragora and the superb Tintorettos in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco because the buildings were so dark. Even today, for want of coins to slip into a lighting contraption, visitors have only a few minutes to contemplate frescoes and paintings. Furthermore, it took money and free time to travel around Europe discovering the sculptures and paintings of other cultures. Wandering at will and at one’s own speed around the Louvre’s Grande Galerie was, therefore, a priceless experience—both literally, because admittance was free, and metaphorically.

The most significant phenomenon in the French arts scene in the early nineteenth century was therefore incontrovertibly the public exhibition of a huge number of masterpieces. In 1793, during the Reign of Terror, the Louvre opened its doors to the public under a new name, the Central Museum of Arts. The planned program for each “decade” (the ten-day period with which the revolutionary government had replaced the seven-day week) was for the first five days to be reserved for artists and copyists, the next two for cleaning, and the last three for the general public. A crucial innovation, besides the open-door policy, consisted in not simply displaying a great variety of works but in arranging them in what was intended to be an educational way.

Immediately after the monarchy fell in 1792, the government started confiscating works of art held in monasteries and churches as well as the assets of the first émigrés. At least some of these works would end up in the Louvre. In addition, treasures from the many royal châteaux were transferred to Paris. The surplus of more than one hundred paintings was stored in Versailles in the Superintendency, the administrative building responsible for the upkeep of royal palaces.

The number of works rose spectacularly in 1794 thanks to the military conquests of the Revolution and Napoleon, because at the time every victory was accompanied by systematic pillaging in conquered territories. The looting of art predates revolutionary and imperial wars but the importance, quality, and sheer number of works of art seized in this particular period were beyond imagining. Convoys laden with paintings by Rubens, van Eyck, and Rembrandt appeared in Paris after Brussels was taken in July 1794, and later the fall of Gand and Anvers provided more Flemish art. Over two hundred paintings were confiscated in the Netherlands. Similar thievery occurred in Germany, and on an even greater scale in Italy.

Advertisement

As soon as Bonaparte was made a general and posted to the army in Italy, he appointed specialized envoys to select works of art, manuscripts, and zoological and botanical curiosities, and these remarkable men (Gaspard Monge, a great mathematician; Claude-Louis Berthollet, a genius of a chemist; Jean-Guillaume Moitte, a renowned sculptor; and the botanist André Thouin, former head gardener of the Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants, now the Jardin des Plantes) not only succeeded in making sound choices but also proved immensely talented organizers. The French justified this plunder by claiming that these treasures would now belong to the people rather than to foreign despots.

Thouin ensured that these trophies made a far from discreet arrival:

Should we bring precious spoils from Rome like sacks of coal and have them unloaded onto the quay by the Louvre like crates of soap?… No, the whole population must be invited to join the party…. Every class of citizen will see that the government has thought of them, and each of them shall have his own share of such a wealth of booty. They shall see how a republican government compares to a monarchy which makes conquests only to enrich its courtiers and satisfy its vanities.

On July 28, 1798, the entrance of a triumphant parade was marked with great celebrations. A procession of exotic animals—lions, camels, and bears—preceded four copper statues of horses, the pride of the façade of Saint Mark’s basilica in Venice, followed by more than thirty carts carrying large classical sculptures, and lastly many of the most famous paintings of the Italian Renaissance: Raphaels, Titians, Tintorettos, and a huge Veronese, The Wedding at Cana. The organizers were aware of how fragile these works were, and did not display them in the open air. Sculptures and paintings were not removed from their cases until they had been allocated a space in the galleries, and the fact that not one of them came to harm during these long journeys, mostly from Italy, considerably impressed the French themselves and foreign visitors.

These consignments continued until the end of Napoleon’s conquests. The extraordinary profusion of works of art necessitated a complete reorganization of the Louvre, and this was undertaken under the direction of Dominique Vivant Denon, a diplomat who was passionate about art. A large proportion of French School paintings in the Louvre were sent back to Versailles where a museum dedicated to the French School was established. Substantial alterations were made at the Louvre, and at times it was closed, but as soon as the doors reopened people flocked to see its treasures. The famous portraitist Mme Vigée Le Brun was quick to visit as soon as she returned to Paris, having fled in 1789 and come back under the Consulate in 1802.

She wanted to go alone so as not to be distracted, and was so transported in her admiration of such beauty that she did not notice the staff had closed the doors. She was beginning to think she would have to spend the night among the glorious statues, which now looked like terrifying ghosts, but she eventually found a small door on which she knocked so loudly that someone came to let her out.

A few months later the Musée du Luxembourg, housing the collection started by Marie de’ Medici, welcomed its first visitors. The galleries of the Palais du Luxembourg had been open to the public for a short period in the eighteenth century but after the Comte de Provence, brother of Louis XVI, had assumed ownership of the site, it was closed to visitors. Watteau had to scheme to be admitted covertly to study Rubens’s Marie de’ Medici cycle. A third major museum, the Musée de l’Histoire de France, was set up at Versailles by Louis-Philippe in 1837.

This sort of public access was completely unprecedented in Europe. German princes and English aristocrats had always allowed people to visit their collections but visitors usually had to be recommended. Vigée Le Brun was disappointed that in London’s museum the only exhibits were minerals and stuffed birds, brought back from Captain Cook’s scientific expeditions. The National Gallery opened very modestly in 1824 with a collection of thirty-eight paintings purchased from John Julius Angerstein, a London banker. Even when some galleries were, in principle, open to everyone, the public had to comply with restrictive rules: for example, the requirement that visitors should have clean shoes if they were to visit the public rooms in Vienna’s Imperial Palace implied that they could afford a hansom cab if not a private carriage, and were therefore relatively far up the social scale.

Advertisement

If France had heeded calls to restore great quantities of plundered artworks to conquered countries after the fall of Napoleon in 1815, the Louvre collection would have been seriously depleted. The French state fought back so energetically that the museum managed to keep almost half the works it had acquired. Several pillaged states lacked the funds to finance repatriations. Some of the smaller Italian states agreed to sell their works of art, and many settlements were reached. Florence relinquished a number of Cimabues but would not back down on the return of some highly prized marble tables. The negotiations were brutal, the general public took great interest in them, and they did nothing to dent the museum’s reputation.

The generation of writers who reached adulthood during the Restoration, which began in 1814 (among them Vigny, Balzac, Hugo, Gautier, and Dumas), witnessed a period of extraordinary artistic effervescence and for at least some of them this compensated for the lack of thrilling imperial conquests. The excitement of this period was due not only to the opening of the museum but also to the close friendships between painters and writers. Bohemian artists had elected to live in the Doyenné quarter of Paris to the south of the Place du Carousel, an area that Balzac would describe in Cousine Bette. It was a quarter condemned to be demolished, and a whole colony of artists set up house there, drawn by the modest rents. According to Théophile Gautier, “an encampment of picturesque, literary bohemians” lived “a Robinson Crusoe existence” in the quarter and it became a retreat for writers, artists, and musicians.

Interestingly, many writers such as Gautier, Vigny, Alfred de Musset, and Eugène Sue spent time as pupils in artists’ studios, and painters reciprocally mingled in the literary groups that grew up around the Romantic movement. The name Jeunes-France (Young-France) was coined for all these creative types who distinguished themselves as much by their choice of clothes as by their talent, and who regularly met at Victor Hugo’s house. Between them they formed what amounted to a federation of the arts.

Eugène Fromentin was both a painter and a writer, Victor Hugo a commendable draftsman. Eugène Sue painted a few sea views and although he soon abandoned the paintbrush for the pen, he remained close to his master, Theodore Gudin, a great specialist of seascapes, and was a dear friend of the famous caricaturist Henri Monnier. Théophile Gautier’s first ambition was to be a painter but, discouraged by how difficult it was, he turned to writing. The Goncourt brothers thought they would make careers as watercolorists. It is hardly surprising then that painters’ studios saw frequent visits from all these writers.

“Poets make friends with musicians, musicians with painters, painters with sculptors…the one replies in madrigals to what the other gave him in vignettes,” wrote Stéphane Guégan in his biography of Gautier. When confronting the Classicists in the furor surrounding Victor Hugo’s controversial play Hernani, his friends “called to arms from the world of literature and music, and from the studios of painters, sculptors and architects.” The critic Sainte-Beuve commented with some distaste on the existence of “a society of young painters, sculptors and poets…who depend far too much on the advantages of partnership and camaraderie in artistic matters.” Puccini’s very popular opera La Bohème, which was based on a novel by the contemporaneous Henri Murger, brought to life all the turbulence and energy of this world by depicting the interwoven lives of four artists: a painter, a poet, a musician, and a philosopher.

All these young artists endlessly visited one another and would meet at, for example, Achille Devéria’s studio, where Balzac, Hugo, Musset, Alphonse de Lamartine, Liszt, and Sir Walter Scott all posed at one time or another. This constant intimacy explains why novelists of the period so frequently featured their artist friends in their work, and why they were influenced by the way these friends looked at the world. Painting had become an almost inevitable literary subject, particularly as curiosity about art was now something of a social phenomenon.

Everyone visited the Louvre, especially artists—both masters and pupils. Beginners spent whole days in its galleries because at the time their craft was learned by copying. The museum also attracted the inquisitive and the idle. It was warm in winter thanks to its modern heating system, there was always something exciting to look at, and it was a respectable place to meet a lady as she could stroll alone in the galleries without provoking comment. Finally it was a draw for the uneducated, who clutched a booklet that listed the subject of each painting and gave a few explanations. The general enthusiasm reached every stratum of society. German and English tourists were amazed by the number of visitors, and claimed to be offended by how filthy and vulgar they were. In 1819 a Prussian diplomat, Karl August Varnhagen, enjoyed everything he saw at the museum but regretted the presence of “fishwives, soldiers, and peasants in wooden shoes,” and he justified his contempt by quoting Goethe: “Works of the mind and art are not for the mob.”

Baudelaire was more indulgent, laughing about two soldiers staring at a picture of a kitchen. An error in the catalog listed it as one of Napoleon’s battles. So where’s the emperor? one of the men wondered. You idiot, his friend replied, can’t you see they’re making soup for his return? And the two men walked on, as pleased with themselves as they were with the painter. Wilhelm von Humboldt, brother of the famous explorer Alexander von Humboldt, founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin, and a driving force in setting up Germany’s museums, was full of admiration of the Louvre and even went so far as to recognize that the only way to safeguard ecclesiastical treasures was to transform them into works of art by exhibiting them.

This enthusiastic response from foreign visitors may not have justified France’s looting but it certainly bore witness to the extensive interest generated by the Louvre and, more particularly, by the way it was organized. The galleries in various European châteaux—particularly in Germany—that were set aside for works of art and were opened selectively to anyone who asked had none of the Louvre’s educational ambitions, and their curators blithely juxtaposed curios, objets d’art, paintings, and sculptures.

According to Balzac, Parisian eyes had a boundless appetite:

These eyes consume…endless exhibitions of masterpieces,…twenty illustrated works a year, a thousand caricatures, ten thousand vignettes, lithographs and engravings.

It would, in fact, have been impossible for French writers to have been indifferent to the audacity and constant change in painting at the time. How could they have failed to be enthusiastic about Géricault and Delacroix, then Courbet, Manet, and the Impressionists? And appreciating their contemporaries did nothing to stop Balzac, Flaubert, Baudelaire, Zola, or Proust from profoundly admiring art from previous centuries.

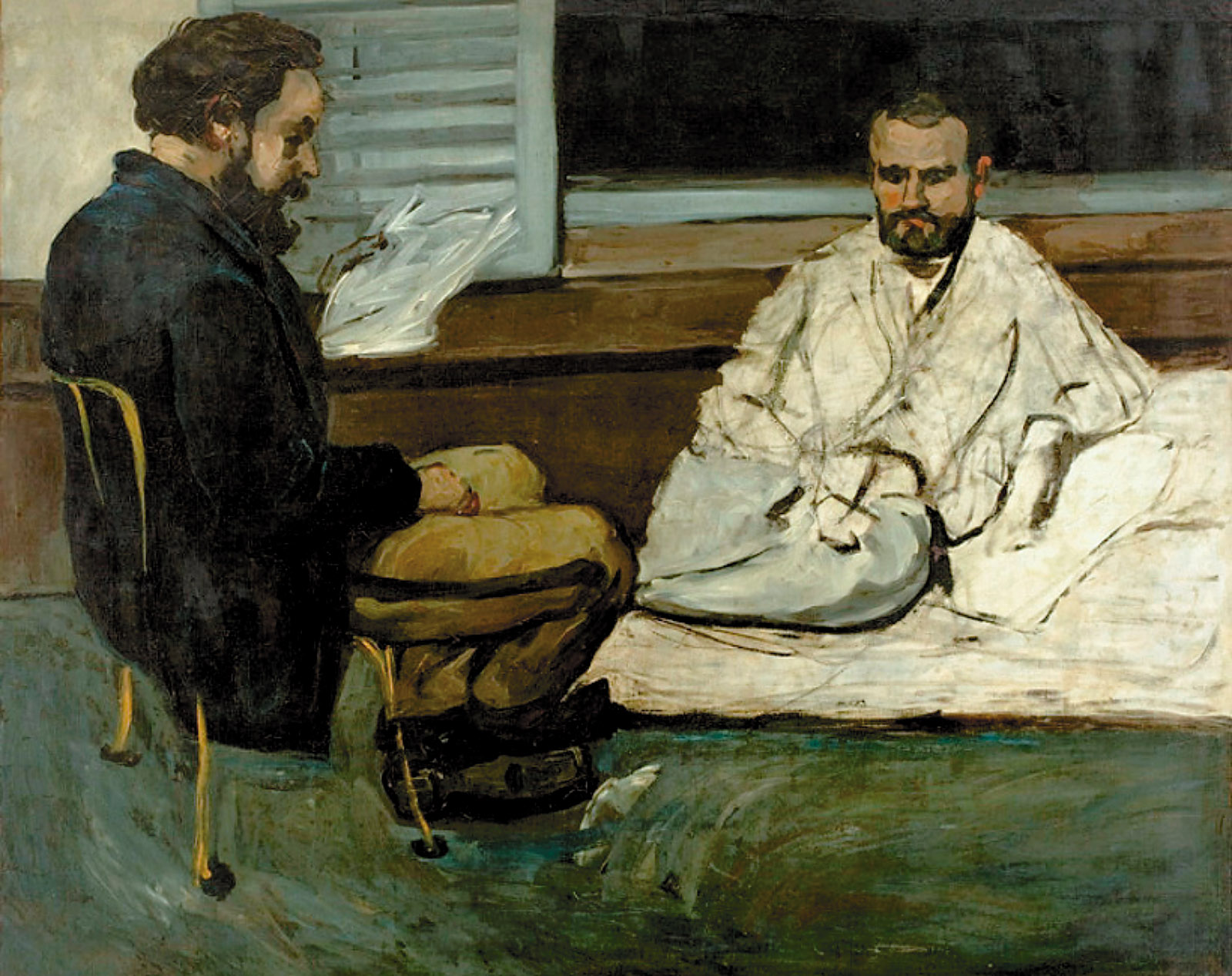

Parisians were not alone in opening their eyes; during the French Restoration a great many Americans came to Paris, drawn by the capital’s thriving arts scene. Among them, Samuel Morse, who would go on to invent the famous code and who had great ambitions as a painter, virtually took up residence at the Louvre, spending hours perched on an impressive scaffolding to get a closer look at the paintings. In the end he decided to paint the Salon Carré but to fill its walls with his favorite paintings, thus creating what amounted to his ideal museum. The result was a huge, six-foot-by-nine-foot canvas featuring thirty-eight paintings, including the Mona Lisa (see illustration on page 33). He took the painting back to America to exhibit it but, unlike the Louvre, he charged admission. (From this October to January it will be at Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.)

The notion that art belonged to the people was now entrenched in the collective consciousness, and the working classes continued to visit the Louvre throughout the nineteenth century. It is no coincidence that in Zola’s L’Assommoir (The Drinking Den), written in 1877, he has Gervaise’s wedding party spend the end of day at the museum. Zola was very aware that the Louvre, along with the regular Salons, had become a part of Parisian life like parades and races. Of course, he did not claim that the populace experienced much artistic sentiment or could offer any serious judgment of the works on display:

Shopkeepers in silk dresses and workmen in jackets and round hats gaze at these pictures hanging on walls the way children look at the illustrations in a new book…. But this is no less a gradual education of the masses. You cannot stroll amidst works of art without taking a little bit of art away inside you. The eye develops, the mind learns to judge. This is still better than other Sunday entertainments, shooting galleries, skittles and fireworks.

A great many writers suggested themselves to me to illustrate the extraordinary transformation brought about by this fascination with art among the French. In my book The Pen and the Brush I focus on five—Balzac, Zola, Huysmans, Maupassant, and Proust—first out of personal choice but also because these authors each in his own way truly invented a visual style of writing. Equally significantly, the gallery of painters they dreamed up allowed them not only to air their views on the art of their day, but also to depict the complex relationship between artists and the general public. There is a whole world of possibilities between Balzac’s genius, Frenhofer, who despairs of ever convincing his fellow artists of his vision, and Proust’s master, Elstir, who has the patience to explain his art like an optician offering a myopic customer different-strength lenses until he can see clearly.

—Translated from the French by Adriana Hunter; translation copyright © 2017