In an article on André Derain in How to See, his first collection of art writings, the painter David Salle says that, as “a former enfant terrible myself,” he has been drawn to the French artist’s story—that of a figure who was crucially a part of the beginnings of modern art and then notably came to reject the modern spirit. Salle’s point isn’t exactly that, like Derain, he was a pathbreaking painter who has become a traditionalist. Salle would seem to mean by “enfant terrible” (a term with which he refers to himself elsewhere in these pages) more that, as Webster’s Collegiate defines it, he was once a “young and successful person who is strikingly unorthodox, innovative, or avant-garde.”

This would fit Salle, who by the beginning of the 1980s, as he was turning thirty (he was born in 1952), was making some of the most powerful of the new works that were dramatically altering the art scene. Of course, many of the arriving artists of the time were to a degree enfants terribles in the sense that they were young troublemakers. Whether they were painters and included, along with Salle, Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, Terry Winters, Carroll Dunham, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, or whether—as Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince demonstrated—they were artists who used photography (rather than being camera artists on the order of Walker Evans), the new figures of the early 1980s, in their different ways, were turning upside down the rules and shibboleths that had guided the art scene for over a decade.

Conceptual art, which dominated that scene, had put artists (in Europe as well as the States) under a spell. Serious new work, the thinking went, could not be about beautiful, collectible objects, and it was certainly not about the torments or strivings of heroic individuals. It was, rather, closer to being an anonymous quest to document, measure, or question aspects of experience—as when, for example, Douglas Huebler, in 1970, exhibited a group of photographs taken every two minutes during a car trip that lasted twenty-four minutes. Not that conceptual art blanketed the art world. Plenty of artists went on making innovative and striking works that had no connection to it. Yet from the late 1960s onward it could seem, based on what was being shown, taught, and written about, that challenging new art had become a sort of neutrally spirited, faceless, even morally reproving enterprise. It created an era when, as Salle writes, much contemporary art made “people feel stupid.”

Into this rulebound and exasperating art realm there stepped a generation of artists whose concerns were precisely what had been deemed of no account: images on canvas and on film of people, things, and places; ambivalent or admiring acknowledgments of the ubiquity of advertising, the power of movies, and the allure of cartoon drawing styles; the desire to recreate the appearances and emotional textures of contemporary life; and a belief that sexuality could be treated with candor—that is to say, without a playful lustiness, in Picasso’s fashion, or a sense, as the Surrealists made it seem, that psychoanalysis was just around the corner.

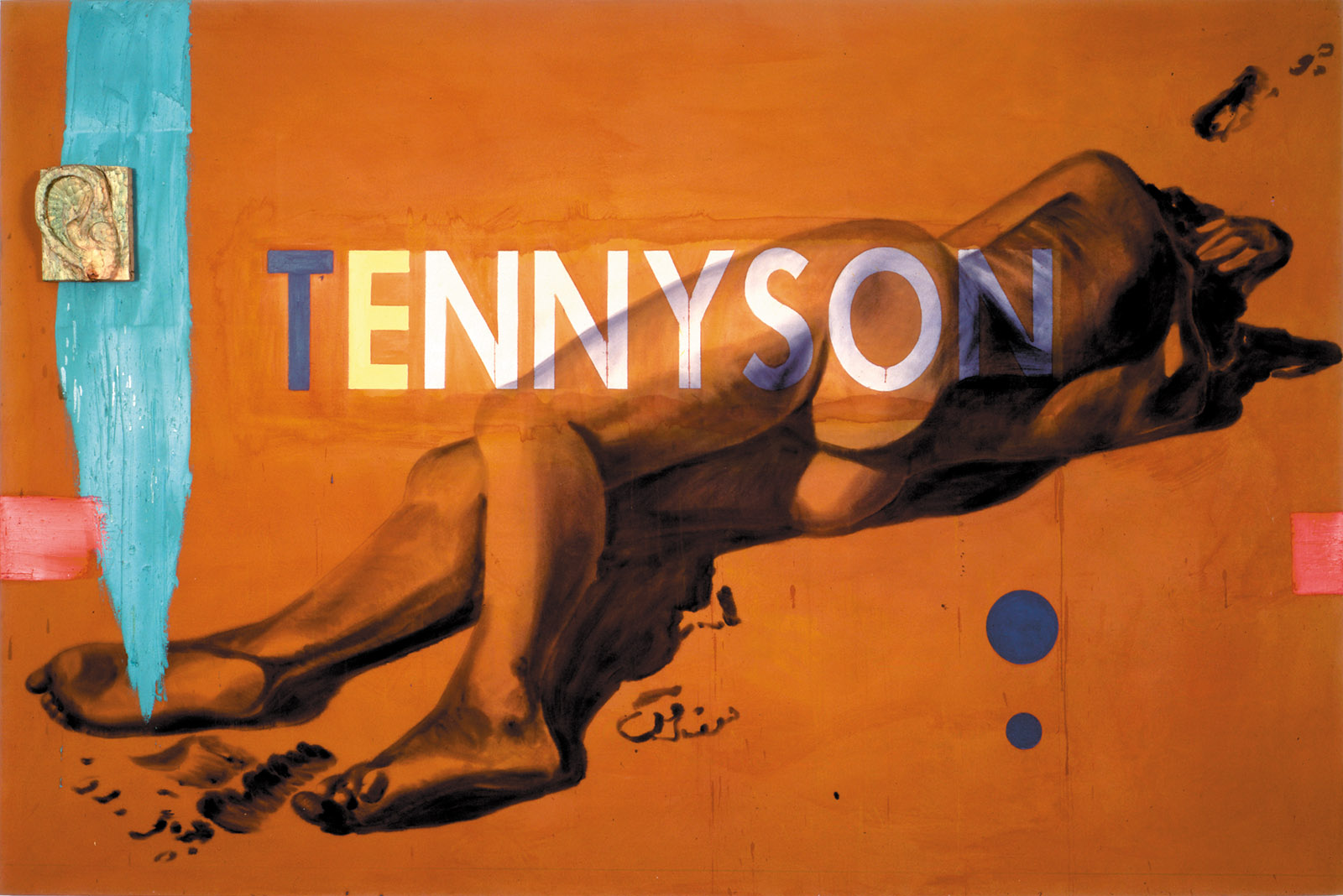

David Salle was not in any official sense the enfant terrible of these artists. Schnabel, a year older, was more at the center of the moment. Making paintings whose surfaces were full of broken crockery, he was almost literally the bull in the china shop. But there was, seemingly from the beginning, a dazzling and steady feeling for balance and control in Salle’s art. In his ambitiously large-size paintings, references to midcentury modern design, recreations of works by known artists, drawn images of people, and sometimes objects affixed to the canvases were all held in states of mystery and tension.

What added to Salle’s nerviness was his particular frankness about sexuality. In his collage-like paintings, the images that were brushed directly onto the canvas, in shades of gray—making them seem photograph-like, shadowy, and ominous—were sometimes of women with their legs spread, or seen wearing perhaps a bra; and making these images part of a shifting world where we might also see areas of decorative design, or references to work by, say, Alberto Giacometti or Max Beckmann, or deft sketches here and there in vivid colors of a bullfighter doing his turns, had a brazen force. Salle’s sexual candor wasn’t, in tone, happily carnal or about the furtive and hidden. It was coolly matter-of-fact.

If being an enfant terrible can suggest attaining a masterfulness without having to labor for years to achieve it, Salle’s status as an accomplished beginner was renewed in the mid-1990s when, with little prior experience as a moviemaker—but with, like other members of his generation, an almost umbilical connection to movies—he directed Search and Destroy, a feature with Griffin Dunne, Christopher Walken, and John Turturro. If memory serves, the 1995 film was a black comedy that, like The Grifters, which it somewhat resembled, was thankfully free of sentimentality. It was a substantial achievement for a near novice.

Advertisement

Remarkably, Salle’s How to See, a collection of essays and reviews written mostly since 2010, has the same seemingly out-of-nowhere assurance. Salle says that when he came to New York in the mid-1970s, he wrote reviews for Arts Magazine to help pay his rent. He doesn’t appear to have done any writing between then and starting up a few years ago, which makes the seemingly effortless skill and variety he shows here as a writer amazing. We feel we are reading the latest from a commentator who has been at it for a lifetime and yet is still making discoveries and sharp, new distinctions.

In pieces that appeared primarily in Town and Country, The Paris Review, and different art magazines, Salle writes on contemporaries of his such as Jeff Koons, Barbara Bloom, and Mike Kelley, and on younger artists such as Urs Fischer, Wade Guyton, and Dana Schutz. There are articles on older artists, including Alex Katz, Frank Stella, and John Baldessari—How to See is dedicated to Katz and Baldessari—and on historical figures, from Piero della Francesca to Francis Picabia. Salle also writes about what it was like, in the early 1970s, being in the first class at CalArts, the influential school that steered students to conceptual art, and he has reprinted remarks to students beginning art school and a commencement address delivered in 2011 at the New York Academy of Art.

Salle states that “the idea for this book” is to catch the way artists think and talk about what they see. He is after, he says, “how” an artwork functions, not “why.” His aim is to be free of the larger cultural themes, or the “macronarratives,” as he calls them, that he believes journalists and academics yoke their perceptions to. He wants to describe the individual artwork not as an illustration of prevailing theoretical, cultural, or historical notions but as an object that we need to, and can, define for ourselves, using our instincts and emotions as our guides.

This is a winning approach, yet Salle to his benefit doesn’t limit himself to what he calls the artist’s “micro” view. He generally does not give as much factual or biographical information on a given subject as a journalist would, but he essentially writes as a critic. In his analysis of Frank Stella’s 2015 Whitney retrospective, for example, Salle’s spirited and astute descriptions of Stella’s ups and downs seem fairly “macro” and little different from the work of other critics (and here the present writer should note that he is among those quoted by Salle from time to time and is thanked for encouraging him to pursue this writing).

What stands out in How to See, at least at first, is the volume’s sheer number of penetrating, to-be-marked sentences or phrases—observations that can be funny, warm, offhandedly erudite, arch, or simply commonsensical, and that intensify the part played by art in our lives and the life of art itself. About the obstreperous work of the late Mike Kelley, Salle shrewdly says that the Detroit artist caught “the emotional brutality and false cheer of American adolescence.” In art school, Salle writes, “our primary mission as students was to impress each other”; and we hear that it is “annoying to be overpraised; it’s like showing your work to your parents.” Reading that certain pictures by Francis Picabia have been “painted with just the right unconvincing gusto,” we become avid to see them.

Salle’s coverage of Robert Gober’s 2014–2015 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art is particularly strong. To be told that this artist’s homespun yet aberrant washbasins and cribs, and his sculptures of hairy legs sticking out from walls, could stem from “the kinds of drawings that might be found in a precocious high schooler’s notebook” is to get in a flash a firmer grip on Gober’s metaphoric art. Salle’s seemingly contradictory perceptions that Gober would make a good psychoanalyst and that if his art were a person “it would be the sort who is quick to take umbrage” both tie together convincingly with his work.

Writing about the late Sigmar Polke, Salle deftly summarizes Polke the person, and indirectly nails his art, with the words: “You can feel that he loves humanity, so long as it doesn’t impinge on his freedom of movement.” On the German artist Rosemarie Trockel, whose 2012–2013 show at the New Museum included images and objects collected from many artists of plant and animal life, Salle writes, in a sentence that is captivating in itself (though I am not sure I fully believe it), that “like the pure of heart in gothic literature, every creature speaks to her.” And his description of Baldessari’s first photographic work and how similar it was to Jean-Luc Godard’s early movies—how both took as their subjects young people, “people a little bit unformed, who are posing”—leads to a notable new way to think about Godard’s influential movies of the 1960s. They are seen as being echo chambers, with the young, inexperienced performers in them acting, as it were, by impersonating actors they had seen in films.

Advertisement

But it isn’t only on art-related subjects that Salle’s prose is alive. When he writes about first going to Baldessari’s studio in a suburb of San Diego, and notes the “coastal bleakness up and down the street,” the words “coastal bleakness” jump out. This is an atmosphere we know but don’t much see referred to, “coastal” usually implying something pleasant. (The two words, like “false cheer,” resemble a passage in a Salle painting, where normally unrelated elements are brought together.) Sometimes Salle simply lets himself be carried away by the rhythms possible in words, as when he talks about the prospect of art school:

Whatever your expectations about the world you’re poised to enter, the simple truth is this: nobody is waiting for you to take a seat at the table of esteemed creators. Nobody’s even waiting for you to take your place at the table of studio assistants. No one’s waiting, period.

That “period” is apt and witty, but it has an obvious sting, and although Salle’s point is the unarguable one that you make your own way in life, the tamped-down anger that a reader feels in his tone appears elsewhere in How to See. It is there in his sense that contemporary art at times seems overrun with the “why,” or the theoretical. His argument isn’t bound up in an essay or two but surfaces now and then in small doses in numerous places. He believes that for many young artists, and certainly for many of the people who write about, teach, and present contemporary art, the story behind the work—the intention of the display—has become the end point.

Salle isn’t the first to note that a good deal of commentary about art has become a toting up of “cultural signs”—or what seems like a concomitant of this: the shapeless, one-thing-after-another, variety-show-like nature of current art. Few writers, though, have gone into these issues with the invitingly informal and nondoctrinaire manner that Salle brings to the job. More importantly, it is possible to have been stimulated by a fair amount of the art of the past few decades and at the same time agree with Salle about “all the ambiguity, equivocation, and uncertainty of the last twenty-five years”—about “how muddled much art of the recent past feels, as if it had been unsure of what to ask for.”

What may be animating Salle’s involvement in these issues is that recent art has become another version of what his generation in the early 1980s—a generation that knew exactly “what to ask for”—wanted to move on from. The waves of conceptual art, which the young painters and photographers of that time swam against, rolled right back in. Then, conceptual art might take the form of documents on paper, viewed detachedly in a vitrine. Now, conceptual art might as easily lend its authority to a spectacularly disorienting, or compulsively neat, arrangement of everything the artist found in the family garage (though such an event could make for a lively show).

Salle is hardly out to defend the artists of his time against what followed them. But without much fanfare, he touches on a significant difference between their work and later developments. He and his contemporaries grew up, in the 1960s, in the landscape of classic modern art, where abstract, formal values were of paramount importance and where, as he writes, the conviction held that “stripping art of unnecessary artifice is the path to greater depth of feeling.” Salle rightly sees that the less-is-more thinking of modern art became a kind of “repression” in its own way (and by the 1960s the adherents of abstract art were practically as dogmatic and stifling as the proponents of conceptual art would be in years to come).

Yet a concern for form in itself, and for the particular physical properties of an art object, were almost ineradicable elements in the artistic makeup of Salle, Dunham, Schnabel, Sherman, and the rest. Schnabel and the others had “the ability to see,” Salle says with real insight, “images and pure form as part of the same continuum.” It is that interplay of representation and abstraction that Salle, understandably, seems to believe has gone missing.

As Salle himself acknowledges, over the years his paintings have “succeeded in irritating a lot of people.” In his pictures he seems to offer a range of experiences and associations, from Giacometti and pensive women to designer lamps and telephones, but he doesn’t make any order out of these offerings. By the same token, a reader of How to See probably won’t put it down believing that Salle is chiefly out to slap the contemporary scene or to bemoan the current standing of his peers. The tenor of these essays and reviews is too many-sided to be caught in a single topic.

This reader felt at times as if Salle’s deepest note might be heard in his evocations of the sheer excitement in being an artist. I have rarely seen this done as often or as inventively. About the current moment: “never before in history have more things been possible in the name of art.” About Picabia: it “must have felt glorious to be so opposed, and so untethered to what had come before. How many get to have that feeling?” About reasons to be in art school: because you “can’t imagine your life without that empowering, free-falling, slightly scary, almost illicit thrill of creating.” These daredevil words, written in the past few years by a man in his early sixties, suggest that in some cases an enfant terrible never stops being one.