Although Robert Lowell was born in 1917, Kay Redfield Jamison opens her new biography of the poet seventy-two years before his birth, in 1845, with a Lowell being committed to the “McLean Asylum for the Insane.” This was Harriet Brackett Spence Lowell, Lowell’s great-great-grandmother, who had been cared for at home until her manic behavior made hospitalization necessary. (Her doctor’s notes suggest mania: “She began to be more excited, which was shown in paroxysms of screaming…. [She] has had scarce any sleep.”) After three years at McLean, Harriet Lowell returned home, but she remained permanently depressed and inaccessible to all. Her son, the poet James Russell Lowell, evoked in “The Darkened Mind” his mother’s terrible isolation even when surrounded by her husband and children:

We can touch thee, still we are no nearer;

Gather round thee, still thou art alone;

The wide chasm of reason is between us;

Thou confutest kindness with a moan;

We can speak to thee, and thou canst answer,

Like two prisoners through a wall of stone.

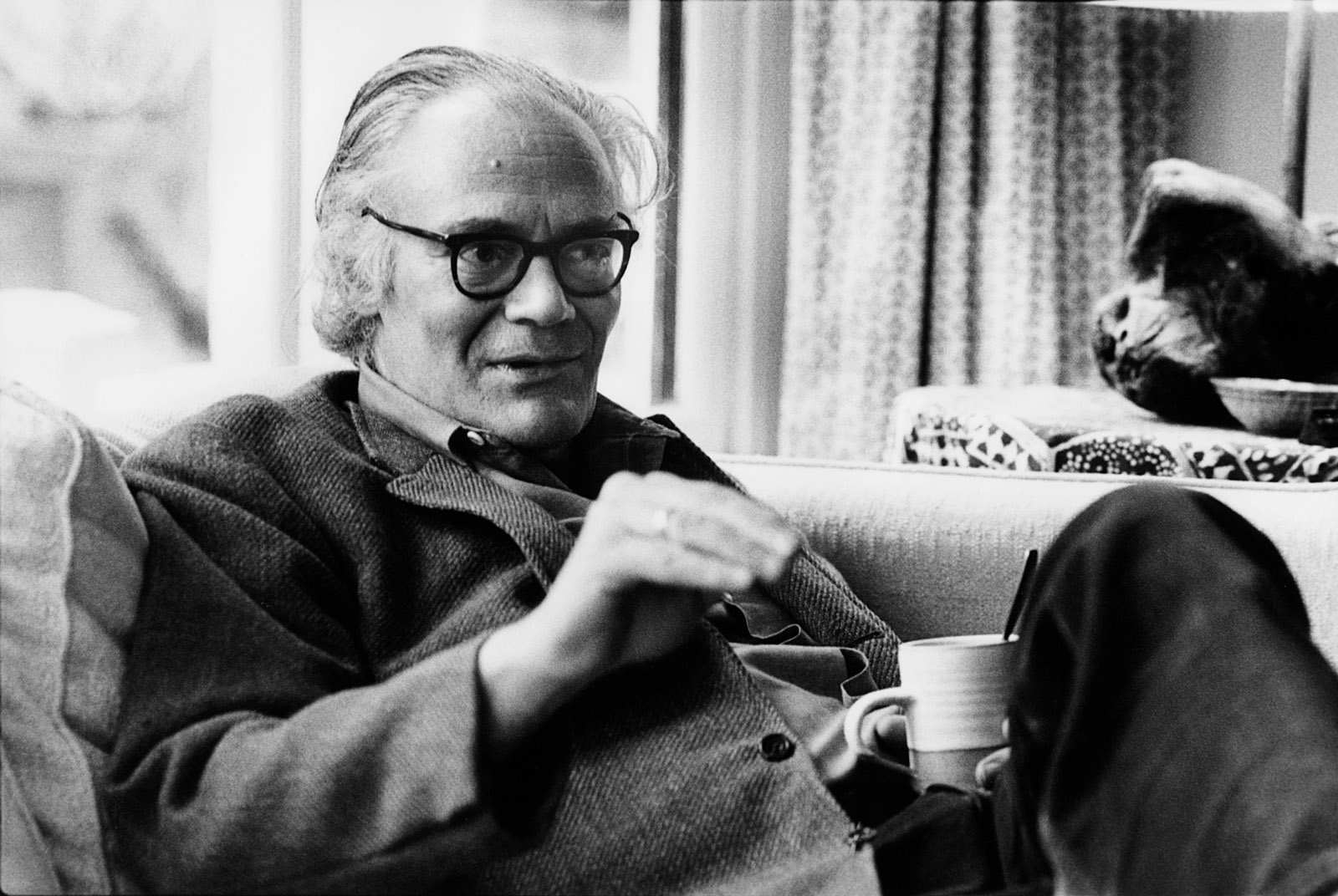

Jamison tracks several generations of Lowells suffering from mental instability; contemporary descriptions of their illnesses (often euphemized as “nervous prostration” or as “paralysis of the mind”) establish the threat of Robert Lowell’s genetic inheritance. Very little of this family history was mentioned in Ian Hamilton’s 1982 biography of Lowell, which many felt relayed lurid anecdotes of successive manic episodes in the life at the expense of a grounded sense of the character of the poet.

Jamison’s remarkable book deals steadily with an intransigent problem: How is one to write a psychologically accurate biography of a manifestly original poet suffering severely from recurrent manic-depressive illness? In the life, which features are aspects of the sane man and which should be ascribed to the deranged one? Jamison, a professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (and an honorary professor of English at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland), approaches Lowell’s vexed life not only with scholarly authority but also with literary talent and confidence; her eloquent memoir An Unquiet Mind (1995), on her own experience of manic-depressive illness, affords her additional warrant to interpret the affliction.

There is a hunger among unaffected persons—often because they have bipolar relatives or friends—to hear what it is like to exist in such unbalance, but medically accurate and emotionally convincing descriptions from patients themselves are relatively rare. Lowell’s own testimony, in both poems and prose (letters, essays, diaries), is ample and harrowing, an autobiographical continuo within Jamison’s own writing. Jamison is the first writer on Lowell to have been given access by his literary executors to all his medical records (and those of his ancestors as well).1 Her comparisons between an external account—a physician’s taciturn notes on an episode—and Lowell’s own dramatic, comic, and ironic rendition of the same episode support her main argument: that a reliable biography of a poet, while relating facts of hospital commitment and mad actions, should infer from the poet’s own art what it was like both to live with recurrent catastrophic illness and to describe and even enact the disorder in several literary genres.

Jamison has long argued for a strong relation between manic-depressive illness and creativity. Although the extent of the connection is still under debate, the stimulus given by mania to certain writers, painters, and composers has been observed historically since classical times. Jamison cites two recent studies that examine large populations and attest to a link between bipolar disorder and creativity in artists.2 She also cites a third study that predicts further advances through analysis of the genome (while remarking of that study that it “has significant flaws in its design; it requires replication”3).

Lowell’s brilliant metaphorical resources animate his narratives of mania, dread, despair, and apathy as again and again he is put in a straitjacket, transported to what is in essence a temporary jail, confined with fellow madmen, and given over to doctors. Treatment of the disease, uncertain and exploratory, amounted to torture of various sorts. Following the death of his mother in 1954, he underwent nearly twenty electric shocks in Cincinnati; shortly afterward his physicians in New York prescribed the new antipsychotic Thorazine (effective in calming mania but unable to prevent recurrence of the illness). Lowell reported to his doctor at Payne Whitney that the drug made him feel “slow witted and helpless” intellectually, “as though I’m carrying 150 lbs. of concrete in a race.” As the delusions of his overexcited mind subsided under treatment, Lowell plunged into the desolation of shamed and frightened depression, devastated by losing to mental illness the higher functions of his imagination and intellect. As he wrote in his thirties to George Santayana:

The peculiarity I seem to have been born with is a character made up of stiffness and disorder, or lethargy and passion. These words are not necessarily the best. The two horses, judgment and emotion perhaps, take many names; but they go together ill at best, and at bad times, one is lying down immobile, the other galloping.

When he could not write poetry (for example, during depression), Lowell wrote excellent and energetic prose. His tragicomic account of his parents’ marriage and family life in “91 Revere Street” (1959) is equaled by his autobiographical essay written during hospital confinement, eventually called “Near the Unbalanced Aquarium”—interestingly, originally named “The Balanced Aquarium.”4 (In the poem “For the Union Dead” the old South Boston Aquarium, visited by the poet in his childhood and subsequently neglected and abandoned by the Irish who rose politically to replace the Boston Brahmins, symbolizes the decline of the city under those whom he saw as interlopers.)

Advertisement

The prose in Lowell’s letters to family and friends is witty, entertaining, and affectionate. Among Jamison’s virtues is her expert eye for the enlivening quotation—aphoristically brief or nakedly revelatory. And she knows that a poem has more to do than describe, that obedience to its aesthetic purposes can deflect and even contest the apparently biographical “facts.” When I said to Lowell about the opening line of “Bright Day in Boston”—“Joy of standing up my dentist”—that hardly anyone would so defy a dentist, he said almost demurely, “Well, actually I went to the dentist, but that wouldn’t have made a good first line.”

Jamison’s tact in approaching the poems is as impressive as her patient amassing of details (the book has eighty pages of detailed notes). Among her three invaluable appendices, two are factual summaries—“Psychiatric Records of Robert Lowell” and “Medical History of Robert Lowell” (the latter, compiled by Jamison’s cardiologist husband, Thomas A. Traill, ends with the poet’s early death at sixty from heart disease).

A third appendix, headed “Mania and Depression: Clinical Description, Diagnosis, and Nomenclature,” introduces the lay reader to the nature and effects of bipolar illness. Jamison, a coauthor of the standard physician’s manual of manic-depressive illness, includes in the appendix the “Diagnostic Criteria for Mania and Major Depressive Disorder,” a merciless medical summary of the malign symptoms of both mania and clinical depression. Bringing the appendix up to date, Jamison also mentions the National Institute of Mental Health’s “Research Domain Criteria” for the illness, a document “that takes into account the rapidly accumulating findings from genetics, neuroimaging, molecular biology and neuropsychology.” To these descriptions of the disorder must be added Thomas Traill’s final remarks concerning its effects on longevity:

Patients with manic depression have significantly shorter life expectancy than normal. Even when, despite the odds, sufferers do not succumb to suicide, or die from overdose, accident, or violence—more or less direct consequences of their condition—…the physiologic overstimulation that accompanies mania can be acutely lethal and surely takes its own toll in the long term.

Jamison is as alert to the poet’s emotional and intellectual suffering under mental illness as she is to the physical manifestations of the disorder.

Although Jamison’s biography necessarily draws on earlier summaries of Lowell’s life, it differs from them in its degree of insight into what it must have been like to exist as Robert Lowell, decade after decade. He was a child so antisocial and rebellious that his parents took him at fifteen to Boston’s Judge Baker Center for psychological evaluation. He experienced his first diagnosed breakdown in adolescence, and left Harvard after two unsuccessful years for the smaller dimensions of Kenyon College (where he studied classics and graduated summa cum laude). He found himself a nascent poet with a wild talent not yet under control. Jamison’s psychological understanding and professional expertise give credibility to the young poet’s actions and reactions.

Jamison treats Lowell’s three marriages (all to writers) and the reverberations of his malady on them without special pleading. After Lowell’s disastrous 1954 breakdown, Elizabeth Hardwick, his second wife—whose dauntless letters over more than two decades, written in pain, love, and fury, establish her as the heroine of the book—admitted to Lowell’s friend Blair Clark:

I knew the possibility of this when I married him, and I have always felt that the joy of his “normal” periods, the lovely time we had, all I’ve learned from him, the immeasurable things I’ve derived from our marriage made up for the bad periods. I consider it a gain of the most precious kind.

Yet in this psychotic break Lowell had unbearably humiliated his wife by his infatuation with an Italian girlfriend, announcing that he was going to divorce Elizabeth. His mania rising, Lowell returned from the affair in Italy and his mother’s death to continue his ongoing lectures at the University of Cincinnati. Flannery O’Connor, with her gift for the sardonic, wrote to Sally Fitzgerald, “It seems [Lowell] convinced everyone it was Elizabeth who was going crazy…. Toward the end he gave a lecture at the university that was almost pure gibberish. I guess nobody noticed, thinking it was the new criticism.”

Advertisement

Jamison’s central sections—“Illness,” “Character,” and “Illness and Art”—embody her intent, declared in the book’s second subtitle, to consider Lowell’s “Genius, Mania, and Character.” She assumes Lowell’s literary genius (exemplifying it by unassailable quotations from the best poems). Equally, she takes for granted the fact of his manic-depressive illness (preferring that term as more exact than the vaguer “bipolar”). Her central argument is that Lowell’s character (insufficiently described in earlier biographies) was both formed by, and strengthened by, a constant fear of recurrent madness and an equally constant grief for the harm he had done. She renders both fear and grief with sympathy, but the sustained power of the book lies in its firm delineation of Lowell’s courageous responses, year after year, to the desolate fate of being two different persons. In mania he was delusory, inhuman, dangerous:

Sometimes, my mind is a rocked and dangerous bell;

I climb the spiral stairs to my own music,

each step more poignantly oracular,

something inhuman always rising in me.

But mania brought the joy (even if delusory) of feeling creative, alive with flights of ideas and exploding metaphors. Clinical depression, which could settle in for months, was another matter. In a formidable paragraph, Jamison makes a collage of Lowell’s remarks on that “formless time of irresolution, forgetfulness, inertia,” “that blind mole’s time,” “dust in the blood”:

He was, when depressed, “inert, gloomy, aimless, vacant, self-locked”; “graveled and grim and dull….” Once well again, he looked back on his depression as “muck and weeds and backwash.” He had to shake off “all the unease, torpor, desire to do nothing,” the “grovelling, low as dirt purgatorial feelings,” the “blank sense of failing.” After mania the “somberness” set in, “the jaundice of the spirit,” the “pathological self-abasement.”

Irrational though it is to ascribe to oneself actions occasioned by biological illness, Lowell’s memory nevertheless attached those moments of “turmoil” to the exhausted sane self: “I am tired. Everyone’s tired of my turmoil.”

Jamison fleshes out—from prose, poetry, letters, and remarks by others—both kinds of suffering, mania and depression alike, incorporating and commenting on relevant poems, especially the famous ones. What she does even more strongly is present evidence of the resilience, courage, and strength with which Lowell faced his lifelong trouble. Year after year the sane Lowell—humorous, congenial, decent, loyal, coruscating in conversation—found lasting friends, first his college classmates (the poet Randall Jarrell and the novelist Peter Taylor) and then later poets, including Elizabeth Bishop, Frank Bidart, and Seamus Heaney. Various colleagues, reviewers, and critics, too, were friends with Lowell for years, in and out of madness: like the indomitable Elizabeth Hardwick, his friends understood that illness in itself cannot be subjected to a moral critique.

The unhappy paradoxes of Lowell’s life ended in a taxi at Hardwick’s door: the poet, returning from Ireland and already dead in the back seat, was carrying for appraisal a Lucien Freud portrait of his third wife, Caroline Blackwood, from whom he had definitively parted. In a letter of 1969 from Israel, Lowell, missing Hardwick, had written her, “God, have mercy on me—may I not die far from you!”

Auden, in “Who’s Who,” wrote of uninspired biography:

A shilling life will give you all the facts:

How Father beat him, how he ran away,

What were the struggles of his youth, what acts

Made him the greatest figure of his day.

A sensibility, as Auden says, cannot be conveyed by a cursory “shilling life.” Jamison has attempted something far more ambitious and more penetrating, commenting biographically on the poems that render madness. She quotes, for instance the final comic tableau of “Skunk Hour,” in which a feral skunk family invade Lowell’s Castine, intent on reclaiming the Maine town for themselves:

A mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail.

She jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

In this instance, Jamison illuminates the desperate earlier part of the poem—“My mind’s not right”—by enumerating the disasters preceding its composition: “Skunk Hour,” she says, “is a work of courage and originality written during, and in the aftermath of, a particularly terrible attack of mania, months of depression and personal upheaval,” but she also reminds us that its last line “is, notably and unforgettably, ‘and will not scare.’”

At other times, Jamison tacks deftly back and forth between a poem and its context: in treating “Mr. Edwards and the Spider,” she supplies the intimate, eerie, personal, and ancestral background with a degree of detail absent (as far as I recall) in critical commentary. As Lowell knew, his mother was a descendant of the Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758); he had intended at one time to write Edwards’s biography. Jamison adds chilling facts from Ava Chamberlain’s 2012 history of the Edwards family:

Edwards’s grandmother was insane—her husband stated in their divorce proceedings that she “often threaten[ed] my Life to Cut my Throat when I was asleep”—and one of her brothers and a sister were declared by the court to be non compos mentis, one a “lunatic,” the other “mad.” Another brother was convicted of murder and executed.5

Veering back to the poem, Jamison points out that in Lowell’s hands the natural spiders of Edwards’s youth become symbols of purposelessness:

The Jonathan Edwards who as a youth had described the beauty of the marching, flying, swimming spiders was now the preacher of hell. Mood had darkened, mildewed. The once billowing spider had spun into an agent of hopelessness: “They purpose nothing but their ease and die/Urgently beating east to sunrise and the sea.”

The reader, even knowing the derivation of “Mr. Edwards and the Spider” from Edwards’s writings, might think some of its lines, in the light of Lowell’s madness, openly autobiographical:

Your lacerations tell the losing game

You play against a sickness past your cure.

How will the hands be strong? How will the heart endure?

But Jamison enlightens the mistaken reader, pointing out that Edwards, in the course of his sermon “The Future Punishment of the Wicked Unavoidable and Intolerable,” paraphrased his own epigraph; “How then will thine hands be strong, or thine heart endure” (Ezekiel 22:14), which was further adapted by Lowell. Ian Hamilton’s biography remarks of the poem only that “almost every line [is] a direct quotation from Edwards’s own writing.”6

By contrast, Jamison’s rapid and absorbing pages untwist the binding interactions of Edwards’s sermon, Lowell’s knowledge of two family histories, and Lowell’s own psychological torment: the reader comes away in possession of the poem. (Although a biographical account of a poem is necessarily incomplete—it cannot trace the implications of Lowell’s choice of genre, allusion, structure, and idiolect—critical studies will take care of those aspects, and will be helped, by Jamison’s scholarship and fine-grained intuition, toward integrating them with the emotions propelling the poem.)

Of course Jamison’s biography relates, as any biography must, the phases of Lowell’s life: the birth to an unhappily married upper-class couple whose very surnames—Winslow and Lowell—reflect their ancestors’ part in American history; the mother’s domination of the boy and her contempt for his father; the youthful intellectual and artistic development; psychiatric treatment beginning at fifteen and continuing intermittently through adulthood; education at Harvard and Kenyon; a brief marriage to the novelist Jean Stafford; a tempestuous “conversion” to an exaggerated Roman Catholicism, soon abandoned; the imprisonment for several months as a conscientious objector in World War II; the successful marriage of twenty-three years to the writer Elizabeth Hardwick and the birth of their daughter Harriet; the important literary friendships; the cascade of prizewinning volumes of verse from 1944 to 1977; the many enterprises in drama and travels abroad; the teaching at Harvard; the third, disastrous marriage to Caroline Blackwood and the birth of their son Sheridan; and the premature death from heart disease at sixty.

Among Jamison’s narratives of these phases, the tale of Lowell’s childhood and adolescence (naturally of particular interest to a psychologist) is the most oppressive. Signs of mental disturbance and of obsession were present in the child very early, so antagonizing his mother that in the eleven-page written report she gave to the first psychiatrist she consulted about him “she does not mention a single positive thing about her son’s personality, character, or abilities,” writing, among other things: “He gave us a miserable time most of the time. He never was a natural child.” One can hardly imagine the suffering endured by a child under the governance of a mother who thought him unnatural, yet this was the irremovable condition of Lowell’s life until he escaped to Kenyon. “The battle of wills in the Lowell family continued, each participant adamant and unbudging.”

Although Jamison recounts, with unflinching specificity, the destructive year-by-year onslaught of psychosis, she takes her view from Lowell’s retrospective accounts of his illness rather than from the aghast observations of spectators. In both his poetry and his prose, Lowell’s griefs and joys are the salient ingredients, and Jamison’s construction of the life takes as its guide the poet’s sensibility and the art it generated. She quotes the caustic, dismissive, and angry reviews his work received, and judges patiently both those and the glowing ones. Although she herself is unequivocal in saying that acts of madness are involuntary, she comprehends the human inclination to ascribe those acts—of a spouse, of a child—to the real person rather than to his illness. And she equally frames, as humanly natural, the fluctuating responses of Hardwick—now rage, now incomprehension, now pity—to the unforeseen third marriage. There are times, as at the end of the story, when Jamison’s reverence for the poet’s bravery and endurance imposes a hagiographic tone. Because she is mounting a counterstatement to the character of Lowell as seen in the Hamilton biography, it is understandable that she should emphasize his literary and moral strength.

One reads this biography—so full of incident—as one would read a novel, led by each page to the next, fearing and hoping as one follows the excruciating volatility of Lowell’s life and the unpredictable evolution of his art. Jamison admires Lowell’s determination not to repeat himself, to make each volume a new venture, from the apocalyptic prophecies of Lord Weary’s Castle to the sad tenor of Day by Day.

She quotes unforgettable passages in which Lowell is at his powerful best, and mostly passes over the less achieved poems—some grotesque early religious pieces, some of the congested late sonnets. As she introduces his incomparable work to new readers, she will remind older ones of the breadth of an art that comprehends so many American experiences (from war to psychoanalysis) and analyzes, in consummate language, so many human passions.

Reading this account of a troubled life, I recall lines from Wordsworth’s The Borderers that could sum up Lowell’s existence: “Living by mere intensity of thought,/A thing by pain and thought compelled to live.” In Jamison’s moving narrative, we see appear, at recurrent intervals, the intensity, the compulsion, the pain, and the thought. Any new reader wishing to begin an acquaintance with Lowell should pick up his New Selected Poems, just now appearing.

-

1

In an appended note, Jamison explains her use of the more sensitive therapeutic records:

I have limited my clinical description in this book to Lowell’s discussions with his psychiatrists about his illness…and his observations about the relationship between his mania and his poetry. These issues are of direct relevance to the subject matter of this book; the more intimate psychotherapeutic discussions that were in Lowell’s records were not; and I did not use them here. ↩

-

2

Both studies were headed by a physician, Simon Kyaga, at the Karolinska, Sweden; the more relevant is the one from 2011: “Creativity and Mental Disorder: Family Study of 300,000 People with Severe Mental Disorder,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 199, No. 5 (November 2011). ↩

-

3

Robert A. Power et al., “Polygenic Risk Scores for Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Predict Creativity,” Nature Neuroscience, Vol. 18, No. 7 (July 2015). ↩

-

4

Lowell Manuscript Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University. ↩

-

5

Ava Chamberlain, The Notorious Elizabeth Tuttle: Marriage, Murder, and Madness in the Family of Jonathan Edwards (NYU Press, 2012), pp. 86–87, 184–186. ↩

-

6

Ian Hamilton, Robert Lowell, A Biography (Random House, 1982), p. 107. ↩