For any novelist, the relationship between the past and the present offers interesting choices. Although working this out often requires cunning and guile, sometimes the simplest strategy, such as a pause in the narrative for pure, unadulterated backstory, is the most effective. At the opening of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, for example, we are in Gardencourt, a house overlooking the river Thames. If this were a play or a film, we could be briskly told how and where Isabel Archer was found in Albany by her aunt, Mrs. Touchett. But James in Chapter Three of the novel will slowly take us back to the time when Isabel is visited by her aunt. It is as if the previous two chapters had not yet occurred. And then in the next chapter James will take up again the story that began with Isabel’s arrival at Gardencourt as though his system were an aspect of the leisure and ease that many of his characters enjoy, or indeed suffer.

On the other hand, in Ulysses, James Joyce allows us to know about the past of Leopold Bloom through darting, glancing reference. A single thought or memory, soon softened by other things that come into Bloom’s glittering mind, lets us know, for example, that his son Rudy is dead and that his father committed suicide in the Queen’s Hotel in Ennis, in County Clare. We are too locked into Bloom’s life in the present to be able to go back to those events in all their drama and pain. Nonetheless, they have a life in the book; they offer density to the present time that is being slowly and lovingly dramatized. They are like a powerful undertone, or a drum roll, or a darker, stranger shade beneath the dominant color.

J.M. Coetzee’s novel Age of Iron (1990) is written in the fierce tone of the present, in the first person, by a woman dying of cancer. The novel, addressed to her absent daughter, is all voice, filled with what the protagonist sees and feels and notices. In Chapter One, in a few lines of dialogue, the past is briskly disposed of as Elizabeth Curren tells the homeless man who has come to haunt her final days: “My husband and I parted a long time ago…. He is dead now. I have a daughter in America. She left in 1976 and hasn’t come back. She is married to an American. They have two children of their own.”

As the book progresses, however, more details of her past emerge. She has been a teacher of Latin and Greek, and thus references to the classical past come naturally to her. And music, too, has mattered:

Letting go of myself, letting go of you, letting go of a house still alive with memories: a hard task, but I am learning. The music too. But the music I will take with me, that at least, for it is wound into my soul. The ariosos from the Matthew Passion, wound in and knotted a thousand times, so that no one, nothing can undo them.

Earlier in the book, a sense of who she has been, and how her soul has grown, are evoked as she sits at the piano and plays Bach and Chopin and Brahms. Then, as she plays Bach for her down-at-heel visitor, she wonders about the spirit of the composer:

When the last bar was played I closed the music and sat with my hands on my lap contemplating the oval portrait on the cover with its heavy jowls, its sleek smile, its puffy eyes. Pure spirit, I thought, yet in how unlikely a temple! Where does that spirit find itself now? In the echoes of my fumbling performance receding through the ether? In my heart, where the music still dances?

This idea of spirit will also be evoked as Mrs. Curren quotes Virgil in the original Latin on “the unquiet dead,” a passage from Book IV of the Aeneid that tells that the unburied will wander the earth for a hundred years, making reference to the rauca fluenta, the hoarse-sounding streams, or as Seamus Heaney translates the phrase, “these gurgling currents.”

What happens to the soul is what animates J.M. Coetzee’s new novel, The Schooldays of Jesus, and its predecessor, The Childhood of Jesus (2013). When the boy who is called Davíd in the novel—although that is not his real name—comes to the town of Estrella with Simón and Inés, his surrogate parents, he is enrolled in an Academy of Dance run by Señor Arroyo and his second wife, Ana Magdalena. When Arroyo’s sister-in-law arrives, she refers to him as “Juan Sebastián,” thus allowing the reader to check (or remember) that the word arroyo in Spanish can mean a stream, which is the German word bach. Davíd’s teacher’s name in German then would be Johann Sebastian Bach, whose second wife’s name was also Ana Magdalena.

Advertisement

This movement of words from one language to another and from noun to proper noun offers, however, only a mysterious set of signposts to The Schooldays of Jesus and The Childhood of Jesus. Arroyo is not a composer. He is not presented to us as a real figure from history, as Dostoevsky in Coetzee’s novel The Master of Petersburg (1994) is offered to us as a figure from the real past. Nor is Arroyo’s wife a singer, as Bach’s was.

Neither can the boy Davíd be simply read as the boy Jesus of the New Testament. Although he is also special in some way, as well as willful and oddly opinionated and, like the figure from the Bible, has what we might call a gnarled parentage, we cannot easily equate him with the man from the New Testament.

Coetzee has brought his characters to an island. Once arrived, they can no longer remember their previous life. Simón tells Davíd:

You arrived on a boat, just as I did, just as the people around us did, the ones who didn’t have the luck to be born here…. When you travel across the ocean on a boat, all your memories are washed away and you start a completely new life…. There is no before. There is no history. The boat docks at the harbour and we climb down the gangplank and we are plunged into the here and now. Time begins. The clock starts running.

This means that Coetzee can now dispose with backstory, memory, time past. The characters in these two novels are haunted by what they do not know and cannot recall. This great emptiness leaves them free to live in the present and interrogate its contours with an intensity that is solid but also ghostly because they are aware that there was an earlier time whose resonance has been erased. “I suffer from memories,” Simón says, “or the shadows of memories. I know we are all supposed to be washed clean by the passage here, and it is true…. But the shadows linger nevertheless. That is what I suffer from.”

The world they now inhabit, where Spanish is the local language, has some relationship to the real world, as did the setting for Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980), but even though it is more modern than the setting of the earlier novel—there are horse races and machines—it is not precise. This allows Coetzee a freedom not only to work with allegory and mystery but to shape circumstances according to the needs of his fiction. It also allows him to make sly jokes, as when, in this world freed from history, the boy sings in what he thinks is English, but the stanza quoted is in fact in German. It is Goethe’s poem “Erlkönig,” about an anxious boy and his father, which Schubert set to music.

Taking the past out of the equation allows fresh energy to be released, as the characters live in the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns. It allows Coetzee to ask the question set by Elizabeth Curren when she looked at an image of Bach: “Where does that spirit find itself now?” And it allows him to answer the question with the same degree of fictional playfulness and fierce seriousness that we associate with his own spirit as a novelist.

His characters in these two books have moved out of the novel we might call life into a new sort of novel called afterlife, a place that nonetheless holds on to some of the shapes and outlines of the way things were. This allows us to see Davíd, Simón, Inés, the Arroyos, and a murderer called Dmitri not as archetypes or as characters whose affect and energy have been greatly reduced, but as shadows who have once more been offered substance. Now, however, they are in a fictional space deprived of hinterland. In The Childhood of Jesus, Simón wonders: “Have you ever asked yourself whether the price we pay for this new life, the price of forgetting, may not be too high?” and, since novels in general depend so much on the idea of hinterland, the reader may well say, as Simón does, that “things do not have their due weight here.”

This absence of weight lets the characters experience the world more sharply and starkly. It means that the arguments they have, the questions they ask, the conflicts among them, and the pain they endure become more deeply etched on the reader’s mind and imagination because they live in the fixity of time present, without any of the past’s burdens.

Advertisement

This could be life after death, a place where Bach now teaches dancing and where Jesus preaches unnecessarily to the elders. One by one, they have become shades. But more than that, it is a place where a novelist who has set many of his masterworks in very precise places and times can take greater risks with the form of the novel to explore matters that have preoccupied him from the beginning of his career, such as the relationship between guilt and forgiveness, or between isolation and community, or between barbarism and civilization, or between parents and children, or between sex and love, or between earnestness and irony, or between the body and the soul.

It remains part of the book’s undertone, of course, that the traditional figure of Jesus as a child was placed in the world so that he could stand apart, assert himself, ask questions, and puzzle his parents and guardians, as Davíd does here. Most of the time in The Childhood of Jesus and The Schooldays of Jesus, the dialogue and the conflict are between the boy and Simón, the man who protects him and loves him as a father might. Simón is loyal, patient, forbearing, decent, ready to listen and explain.

The use of a boy and a man as the two main characters in a work of fiction is also found in W.B. Yeats’s short play Purgatory, first performed in August 1938, some months before the poet’s death. While the father in the play can from the beginning hear and see ghosts, the son is ready to make rational argument, prepared to interrupt the high-flown talk and pierce the poetic tone with ordinary speech. The tension between father and son is also played out in Samuel Beckett’s novel Molloy, in which Moran’s ruminations on his son are handled with a mixture of comedy, sourness, love, and brutality. They operate as an ambiguous parody of family relations. In both cases the boys’ innocence and helplessness allow a stark drama to unfold.

Another tutelary presence in The Schooldays of Jesus may be that of W.G. Sebald. There is a fascinating exchange in The Good Story (2015), a set of interviews between Coetzee and the psychologist Arabella Kurtz, about Sebald’s novel Austerlitz. Coetzee, having expressed his admiration for the novel, says that its subject “has suffered the psychic trauma of being wrenched without warning or explanation from his parents and his language and his place of birth…he is suffering from the trauma of surviving in a kind of half-aware state….”

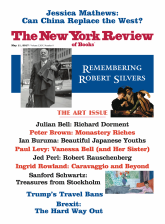

Birmingham Museums Trust

Orazio Gentileschi: The Rest on the Flight into Egypt , circa 1620; discussed by Ingrid D. Rowland in this issue

The name Sebald’s character is given by his surrogate parents when he arrives in Wales is Dafydd, just as the boy in The Schooldays of Jesus is called Davíd. In Sebald’s novel, the figure of Dafydd/Jacques Austerlitz remembers his childhood: “Sometimes it was as if I were in a dream and trying to perceive reality; then again I felt as if an invisible twin brother were walking beside me, the reverse of a shadow, so to speak.” When, in adulthood, he begins to have intimations of how he came to England, this does not offer him any great comfort but further unsettles him, as though, like Davíd in The Schooldays of Jesus, he had begun to haunt his own ghost.

Later in Sebald’s novel, Dafydd/Austerlitz tells the narrator: “As far back as I can remember…I have always felt as if I had no place in reality, as if I were not there at all….” And later still, he describes the repressed suffering and sense of dark isolation resulting from his being moved from his home in Prague in the Kindertransport of 1939 to safety in England:

It was obviously of little use that I had discovered the sources of my distress and, looking back over all the past years, could now see myself with the utmost clarity as that child suddenly cast out of his familiar surroundings: reason was powerless against the sense of rejection and annihilation which I had always suppressed, and which was now breaking through the walls of its confinement.

Dafydd/Austerlitz will muse on the meaning of time and on the idea that “the border between life and death is less impermeable than we commonly think.”

In his book of interviews with Kurtz, Coetzee also invokes Robinson Crusoe. His two Jesus books play with the idea of how life on a desert island can become more intense, almost more true, as does his own version of Defoe’s story, Foe (1986). The life away from the noise of the world offers a zone where more searching questions can be asked, and more antic ones, in which the social space of the novel can be replaced by parable and commentary on what we deem important and how stories come to us.

Coetzee’s island in The Schooldays of Jesus is perhaps closer to the space created by the Argentinian novelist Juan José Saer in The Witness (1983), in which the desert island becomes a place for ironic and poetic musings on exile and the self:

There can be no doubt that when we forget, it is not so much a memory we lose as our desire to remember it. Nothing is innate in us. However neutral and grey the new life we accumulate, it is still enough to cause our most steadfast hopes, our most intense desires to crumble. Experience is heaped on us in spadefuls like the final earth on a coffin in its damp grave. In short, two or three years after my arrival it was as if I had never lived anywhere else.

Coetzee’s two Jesus novels are not only filled with echoes of many other books, but they contain fresh implications of their own. One of these, of course, is that Jesus’s time on earth was like Davíd’s, that he was taken away from a place and handed to guardians who were new to him. He lived in a time and space that were not only unfamiliar but defamiliarized as he began to ask questions and stand apart from his peers.

Like the character in Austerlitz, Jesus was almost aware of his own strangeness, with a sense that there was a missing part of him that he would have to rescue and rediscover in a sort of redemption. His search for wholeness will become the story of the New Testament.

Thus the characters in The Schooldays of Jesus do not muse much on how or why they have come to this new place and been forced to forget where they once were and the identities they have lost. There is too much else going on. Most of the time, they take the present as given, almost ordinary, although the reader never does, which sets up a dramatic tension between the book’s action and dialogue and the reader’s feeling that the characters live, as in a Beckett novel, in a manufactured rather than natural space.

In Diary of a Bad Year (2007), Coetzee’s version of a self or anti-self, or indeed a parody of his own persona, he writes:

Growing detachment from the world is of course the experience of many writers as they grow older, grow cooler or colder. The texture of their prose becomes thinner, their treatment of character and action more schematic. The syndrome is usually ascribed to a waning of creative power; it is no doubt connected with the attenuation of physical powers, above all the power of desire. Yet from the inside the same development may bear a quite different interpretation: as a liberation, a clearing of the mind to take on more important tasks.

This clearing of the mind animates The Schooldays of Jesus and allows Coetzee to brood on matters that have always concerned him. Such as the afterlife of Bach and indeed God. In Diary of a Bad Year, Coetzee writes: “The best proof we have that life is good, and therefore that there may perhaps be a God after all, who has our welfare at heart, is that to each of us, on the day we are born, comes the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. It comes as a gift, unearned, unmerited, for free.” Or the idea of crime and punishment. In The Good Story, Kurtz raises the subject of Dostoevsky’s novel with Coetzee:

Freud read Dostoevsky, of course. It is hard to imagine Freud constructing the concept of the superego without having encountered Dostoevsky’s study of a man who…kills an elderly female pawnbroker, and afterwards finds that he is, despite himself, completely taken over by remorse.

Coetzee responds:

Remorseful confession has a long and complicated history in its literary embodiments. The part of this history that interests me—and has been of use to me as a writer—commences in England of the late seventeenth century, when journalists appropriated the confessions of criminals due to be executed for sensational material, and reaches a high point in the novels of Dostoevsky, who was no stranger to sensationalism but who was—I agree with you—unexcelled in the power of his diagnosis of the complex motives that may underlie a decision—or an impulse—to bare one’s heart. Anyone involved in the therapeutic process ought to read Dostoevsky closely.

Section 24 of Diary of a Bad Year is entitled “On Dostoevsky” and opens:

I read again last night the fifth chapter of the second part of The Brothers Karamazov, the chapter in which Ivan hands back his ticket of admission to the universe God has created, and found myself sobbing uncontrollably…. These are pages I have read innumerable times before, yet instead of becoming inured to their force I find myself more and more vulnerable before them.

It is an aspect of Coetzee’s greatness and range as a novelist that many readers come away from a book or a section of a book by him with the same deep impression as this passage from the Russian novelist made on Coetzee himself. Thus while I admire his Life and Times of Michael K (1983) and Waiting for the Barbarians, the books by Coetzee that I find most powerful are Age of Iron and the early sections of The Master of Petersburg, the novel in which the figure of Dostoevsky comes to St. Petersburg following the death of his stepson.

In both novels, Coetzee ponders the relationship between parents and children, which also animates The Life and Times of Michael K, and on which he casts light in The Schooldays of Jesus, as Simón tries to become, as best he can, a father to Davíd. Age of Iron and The Master of Petersburg are filled with images of estrangement and guilt, which make their way slowly into his new novel in the guise of Dmitri, the museum guard who murders Ana Magdalena Arroyo and is brought to trial.

Dmitri’s guilt allows Coetzee to improvise on the theme of Dostoevsky, just as his creation of the Arroyos gives him permission to imagine an afterlife for Bach and his wife. He lets the shadow of Bach, or his ghost, or his fitful presence, quote from a poem by Rafael Alberti, just as Davíd’s reading of a version of Don Quixote permits Coetzee to invoke the power of that novel.*

The murder of Ana Magdalena is made to seem like the act of a madman, but Dmitri, at his trial, refuses to plead insanity and wishes to be sent to the salt mines, as the theme of his crime and punishment take over the narrative, with Dmitri uttering passionate speeches on what he has done and how he must live. “You think I am not aware of the enormity of my crime…?” he asks Simón.

If they would only give me my marching papers from the hospital I would be off to the salt mines tomorrow…. But they won’t let me out, the psychologists and the psychiatrists, the specialists in deviant this and deviant that…. They are all so interested in me, Simón! It amazes me. I’m not interested in me but they are. To me I’m just a common criminal, as common as weed…. I have no conscience, or else I have too much conscience… I want to tell them, your conscience eats you up and there is nothing left of you….

Later, Dmitri confronts Juan Sebastián Arroyo, seeking forgiveness:

Where shall I turn for relief?… To the law?… The law takes no reckoning of the state of a man’s soul…. I am guilty…. You know it and I know it. I have never pretended otherwise. I am guilty and in great need of your forgiveness. Only when I have your forgiveness will I be healed.

All this is witnessed by the boy whose own delicate conscience has been probed and explored in the book thanks to his oddly outspoken and questioning nature, someone on whom nothing is lost.

We study the boy with care as elements from the New Testament make their way into his story and enrich him, or expand the novel beyond its formal confines into a sort of shimmering parable. When Davíd, having been told that he will eventually acquire a taste for wine, replies, “I am never going to acquire a taste for it,” the reader can smile knowingly, as the reader does in The Childhood of Jesus when Simón says, “Bread is the staff of life. He who has bread shall not want.” Or when the boy in The Childhood of Jesus writes “Yo soy la verdad, I am the truth.” Or when the census is taken and his guardian makes sure that Davíd is not among those counted.

In this novel, Coetzee is at one remove from his previous vocation as a writer. He is playing with time, with names and ghosts, with the shape of his characters’ own experience. In The Schooldays of Jesus and its predecessor he has created a space where many urgent and searching questions are asked by the boy and his guardian about the world and our time in it, and where many other questions about the shape of fiction itself, its mission, its urge to move beyond its own limits, are being slyly and subtly asked by the novelist himself.

-

*

“The first of all novelists, Miguel Cervantes, on whose giant shoulders we pigmy writers of a later age stand,” Coetzee said in his acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize in 1987. ↩