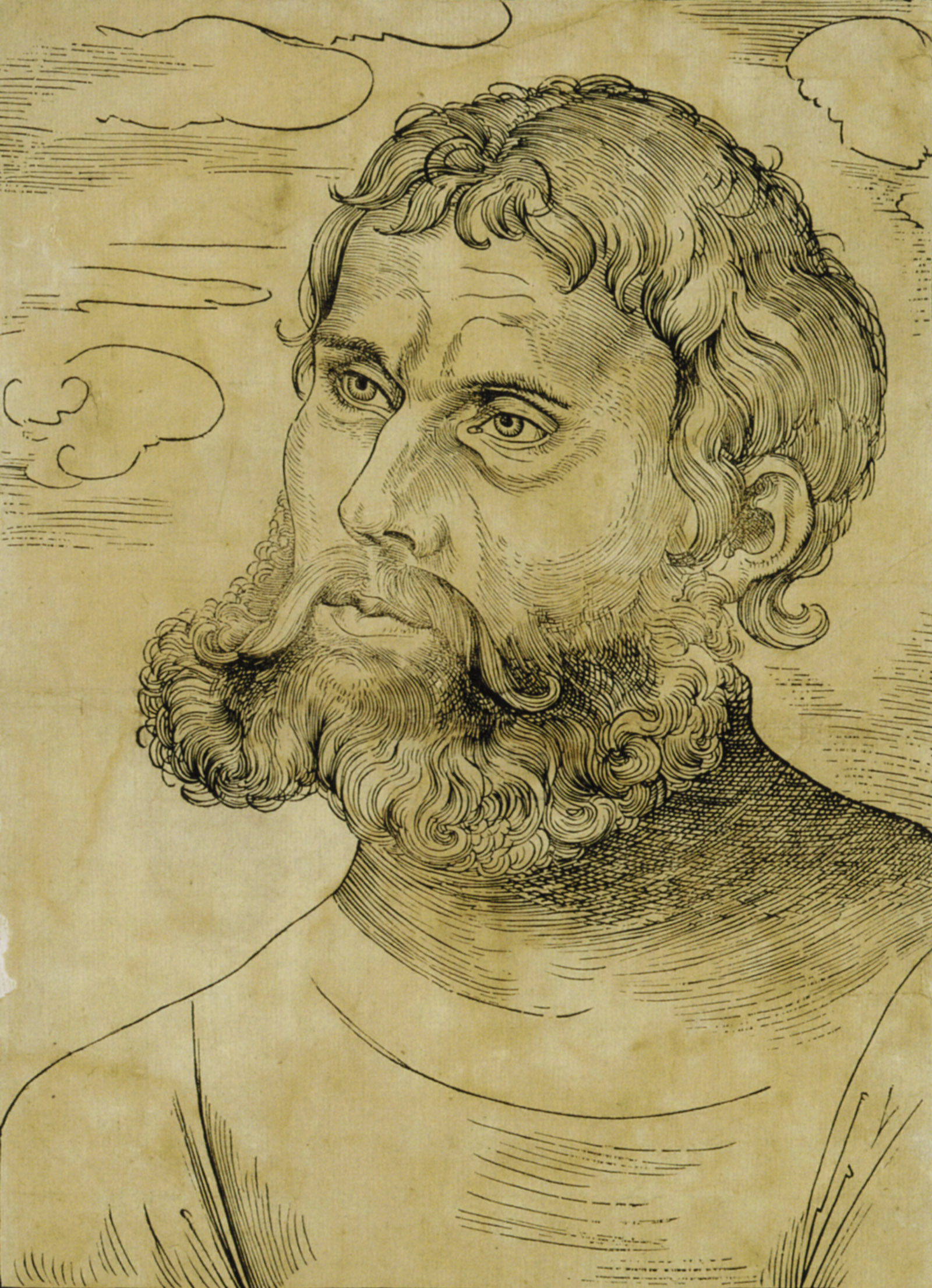

On All Hallow’s Eve of 1517, Martin Luther, Augustinian friar and professor of theology, posted a broadsheet on the faculty bulletin board of tiny, provincial Wittenberg University in the German state of Saxony (which happened to be the door of the church attached to the local lord’s castle). The poster was no Halloween prank; it proclaimed, according to academic custom, his willingness to debate a series of propositions in public. Although he also sent copies of the same broadsheet to important statesmen, churchmen, and academics outside Wittenberg, no one seems to have taken up his challenge to a formal discussion. His propositions were too explosive for that; in blunt, forceful language, they questioned the basic beliefs of the church to which, as a Hermit of Saint Augustine, he had vowed his obedience.

Luther would say that his life’s turning point came two years later, when he had a sudden revelation about the nature of Christian salvation. For his contemporaries, however, the posting of his ninety-five theses in 1517 set off the spark that ignited the Protestant Reformation, and the Reformation in turn marked a fundamental stage in the forging of a collective German identity. To mark the event’s five hundredth anniversary, the Federal Republic of Germany has sponsored a series of Luther celebrations at home and abroad, which began in the fall of 2016 and continue throughout 2017. They include an ambitious series of Luther-themed exhibitions in the United States: major shows in Minneapolis and Los Angeles, with smaller versions of the Minneapolis extravaganza in New York and Atlanta, all providing a fresh, insightful view into Luther’s life and times and the vast, unpredictable forces his rebellion unleashed.

The exhibition catalogs—two impressive five-hundred-page volumes shared by Minneapolis, New York, and Atlanta, and a separate work for Los Angeles—cover a vast range of topics: Martin Luther and Martin Luther King, Martin Luther’s latrine, Lutherans in North America, Luther in Communist East Germany, the unintended consequences of the Reformation. The intensity of their focus is relieved by clever, colorful charts and a bountiful complement of illustrations. It is impossible, given our own recent past, to ponder the Reformation without also pondering its darker legacy of religious warfare, anti-Semitism, and lingering mistrust between Catholics and Protestants, German East and German West; and these are issues the catalogs face head-on.

Yet what drove the friar and his contemporaries to their drastic actions were ideas of transcendent beauty, including the profound inner music behind the cadences of Luther’s oratory and the stirring hymns that set his spiritual armies on the march. To understand this complicated, superbly talented man, and to make the most of the Luther exhibitions, it helps to have a good biography on hand, and Lyndal Roper’s Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet provides expert and spirited guidance. So, in a more specialized way, does Andrew Pettegree’s Brand Luther, a fascinating study of Luther’s pioneering relationship with the printing press that is especially helpful for understanding these exhibitions dedicated in large measure to books and other mass-produced printed works.

-

*

Because “Luder,” the family name, could mean “loose woman,” the ninety-five theses already spell Friar Martin’s name as “Lutther.” When, after a few months, Martinus Eleutherius reverted to a more normal name, it was to our familiar “Luther.” ↩