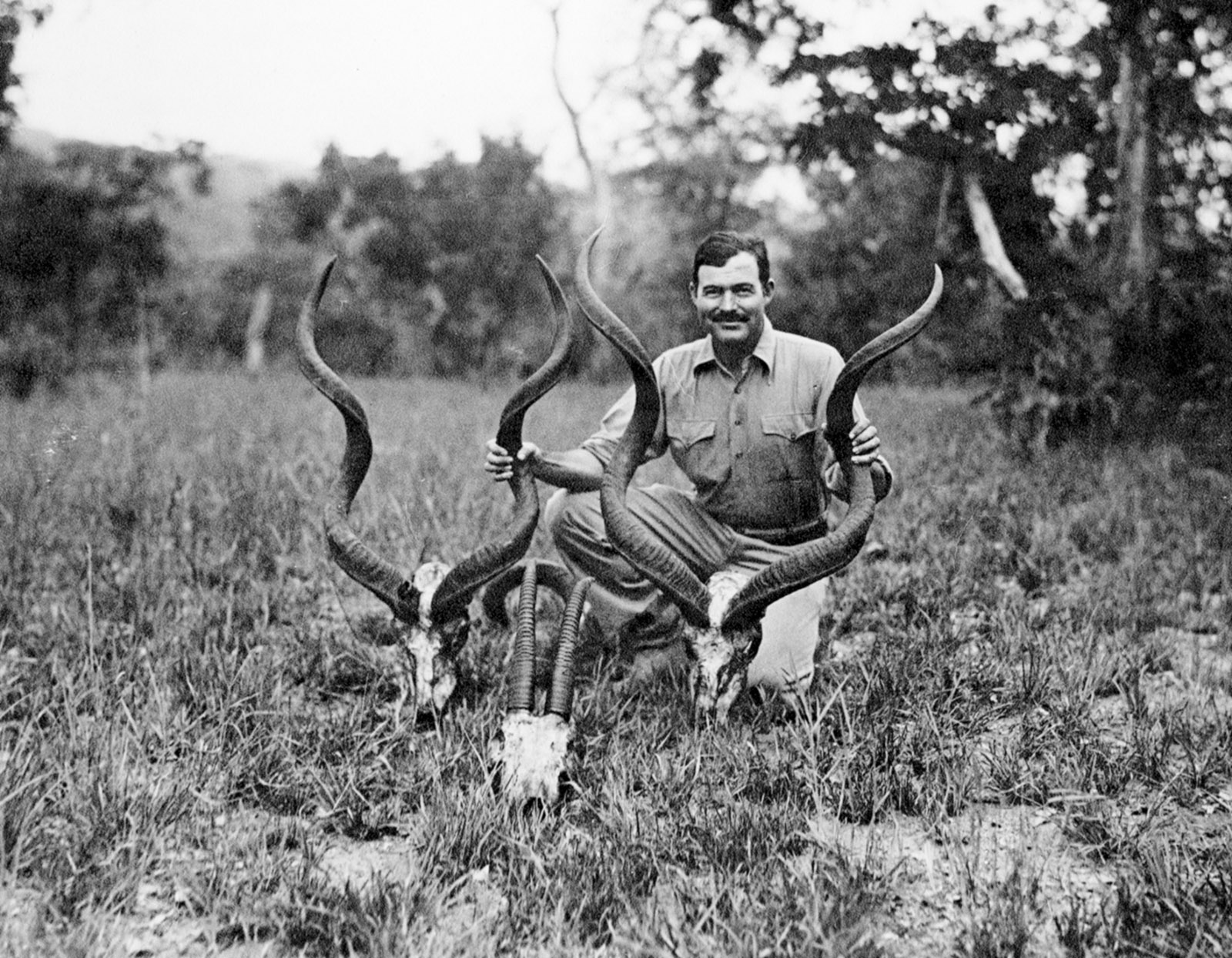

I am not sure whether the National Rifle Association has ever thought of having an official Nobel literary laureate. But if it did there is no doubt that it would choose Ernest Hemingway. There is a coffee table book, published by Shooting Sportsman in 2010, called Hemingway’s Guns. It is a lovingly detailed, lavishly illustrated, and creepily fetishistic catalog of the great writer’s firearms: the Browning automatic 5s, the Colt Woodman pistols, the Winchester 21 shotguns, the Merkel over/unders, the Beretta S3, the Mannlicher- Schoenauer rifles, the .577 Nitro Express with which he fantasized about shooting Senator Joe McCarthy, the big-bore Mauser, the Thomson sub-machine gun with which, he claimed, he shot sharks.

Here he is brandishing his Browning Superposed with Gary Cooper, or showing his Model 12 pumpgun to an admiring Hollywood beauty: “Hemingway enjoyed teaching women to shoot—and what man wouldn’t like to coach Jane Russell?” Here is the Griffin and Howe .30-06 Springfield—“already bloodied on elk, deer and bear”—leaning against a dead rhino. The one gun whose identity the authors seem unsure of is the one with which he took his own life in 1961.

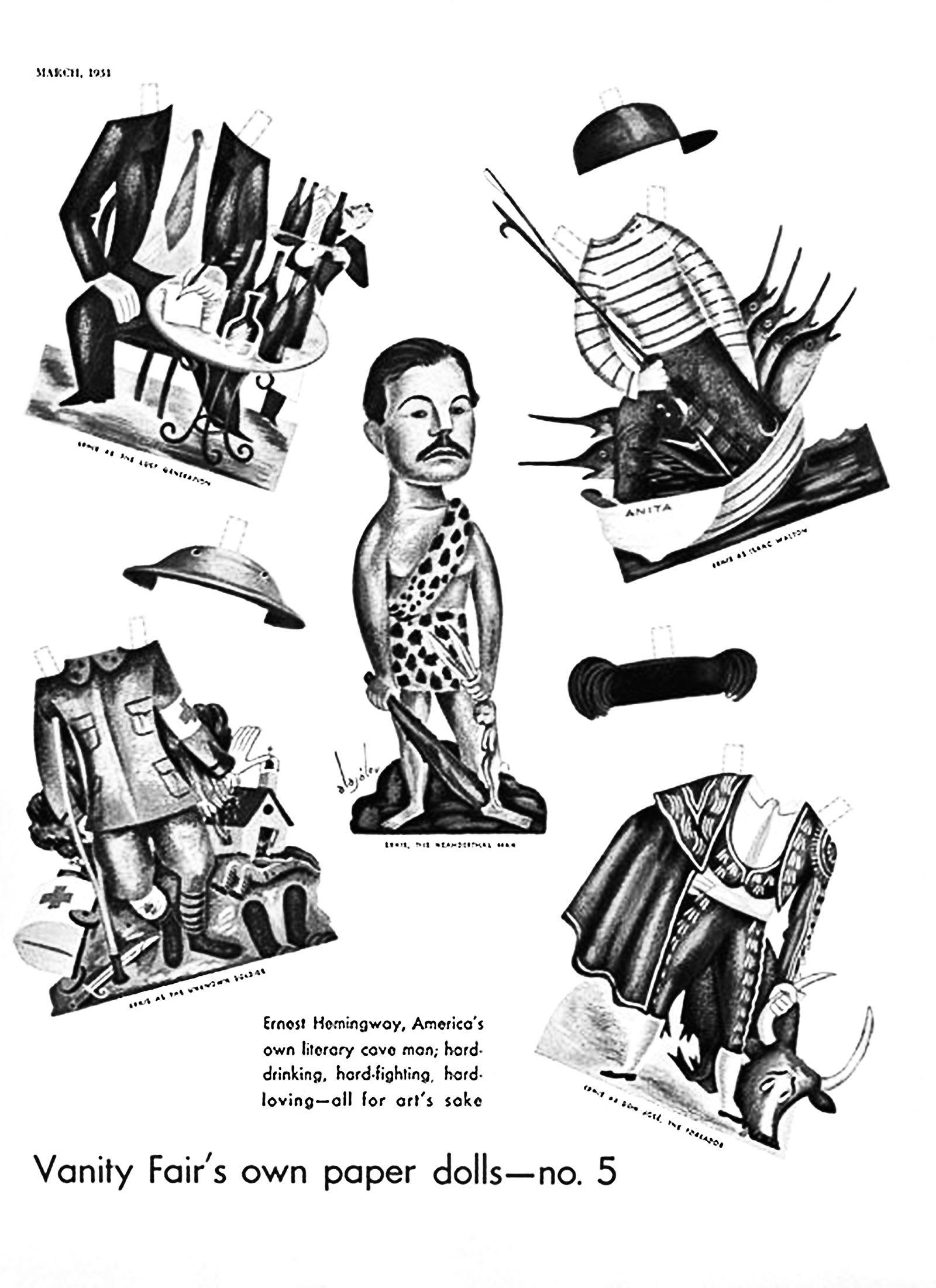

Hemingway’s peculiar variation on American romanticism was a profound connection to the natural world expressed through violent assaults on it. In one of his still-radiant stories, “Fathers and Sons,” we find his alter ego Nick Adams driving through the landscape and “hunting the country in his mind as he went by.” This rapaciousness was what made Hemingway so famous in his own time as the gold standard of American masculinity. As David Earle has shown in All Man!, men’s magazines in the 1950s carried headlines like “Hemingway: America’s No.1 He-Man” and “The Hairy Chest of Hemingway.”*

Yet it is this same alpha-male persona and its relentless desire to possess women and defeat nature that now make Hemingway such a rebarbative figure. It is hard to sympathize with the Hemingway who cabled his third wife, the brilliant journalist Martha Gellhorn, while she was away covering World War II: “ARE YOU A WAR CORRESPONDENT OR WIFE IN MY BED?” Harder still not to recoil from accounts of Hemingway’s slaughtering of lions, leopards, cheetahs, and rhinoceros in Africa or from Mary Dearborn’s deadpan revelation of the fate of eighteen mahi-mahi caught by Hemingway and his cronies off Key West: “They would be used as fertilizer for [his second wife] Pauline’s flowerbeds.”

Add in the overwhelming evidence that Hemingway in his later decades was, in the words of his fourth wife Mary, “truculent, brutal, abusive and extremely childish” and his life story becomes ever more repellent. Yet the appetite for Hemingway biographies appears limitless. Michael Reynolds seemed to say everything worth saying in his five-volume life, published between 1986 and 1999, but the books keep coming. They raise the issue that Gellhorn stated in a letter to her mother when she was about to divorce Hemingway: “A man must be a very great genius to make up for being such a loathsome human being.”

The constant excavation of Hemingway’s life creates the danger of pollution: the loathsome sludge of the personality might seep into the genius of The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, and a score of magnificent short stories. Unless, that is, we can see through the phoniness of America’s number-one he-man to the genuine tragedy of masculinity that is played out in Hemingway’s life and in his best work.

Early in his brisk new biography, James Hutchisson has an anecdote that smells as fishy as the dead marlin in The Old Man and the Sea. It sets up a physical and psychological contrast between the super-manly Hemingway and the weakling James Joyce in Paris in the mid-1920s:

Although Hemingway often made fun of the Irishman’s frail physique, this afforded opportunities for fun and games when they went out drinking together, as they did frequently. When Joyce got drunk and challenged some stranger in a café to settle things manfully, he would simply defer to his companion, saying, “Deal with him, Hemingway! Deal with him!”

Did Joyce really go around picking physical fights in bars? If so, his biographers have missed it. Michael Reynolds, in his authoritative Hemingway: The Paris Years, makes no mention of this delicious anecdote. The origin of the story, so far as I can tell, is Hemingway’s boasting thirty years later. He tells it an interview with Time when he won his Nobel Prize in 1954. And the context makes it obviously bogus. The tale of the frail Irishman hiding behind the manful American is part of a longer quotation in which Joyce allegedly tells Hemingway that “he was afraid his [own] writing was too suburban and that maybe he should get around a bit and see the world.” Nora, Joyce’s future wife, is listening in and adds her approval: “His wife was there and she said, yes, his work was too suburban—‘Jim could do with a spot of that lion hunting.’”

Advertisement

What makes the whole story so clearly specious is that Hemingway’s earliest lion-hunting exploits date from 1933, around a decade after this supposed conversation. Essentially, the Joyces are supposed to be admitting in the mid-1920s that Joyce would be a much better writer if only he were more like the Hemingway of later decades, the world-traveling he-man and hunter, and less like the weedy fellow who needed his bigger companion to “settle things manfully” on his behalf.

In one sense, this episode tells us nothing more than that Hemingway was a compulsive liar and that Hutchisson is foolish to fall for his bragging. The idea of Joyce on safari suggests the possibility of a parlor game: Proust in space, Kafka at the disco. But behind it there is an immense sadness. For this woeful fabrication substitutes for something that might have been real: Hemingway did have a deep connection to Joyce. His two earliest—and best—novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, pick up on what Joyce had done in Ulysses. As Hemingway admitted to George Plimpton in a celebrated Paris Review interview in 1958, “the influence of [Joyce’s] work was what changed everything, and made it possible for us to break away from the restrictions.”

These restrictions were partly questions of frankness about sex and the body and partly questions of style. Hemingway made wonderful use of the freedom that Joyce had created. The tone of his masterly Nick Adams stories comes from Dubliners: it is impossible to imagine his first fully achieved piece, “Indian Camp,” for example, without “Araby,” and we can see in Seán Hemingway’s introduction to the new edition of the short stories precisely how his grandfather ruthlessly cut eight pages from the beginning of that story to plunge the reader, as Joyce does, straight into the stream of the action. The long interior monologue of Harry Morgan’s wife, Marie, that ends To Have and Have Not may not be a worthy successor to Molly Bloom’s in Ulysses, but at least Joyce gave Hemingway permission to try.

However, even these influences may be less important than something else that Joyce gave Hemingway: a specific idea of maleness. That idea is the opposite of the persona Hemingway would later forge—the hero who “settles things manfully.” Joyce gave us, in Leopold Bloom, the hero who settles nothing and is not at all manful, the pacifistic little man who just lives with Molly’s cheating on him with Blazes Boylan. Hemingway’s great tragedy is that he delved deeper into this unmanliness but then turned himself into a parody of the very masculinity he had subverted. For all his talk of courage, his is perhaps the greatest loss of nerve in twentieth-century literature.

Hemingway had imaginative access to two things he hid behind his outlandish public image—a complex sexuality and a deep trauma. Since the publication in 1986 of the unfinished novel The Garden of Eden, which he had worked on fitfully from 1945 until 1961, it has been obvious that he was drawn to the excitement of crossing sexual boundaries. The he-man was at least in part imaginatively a she-man. It was already clear that Hemingway was drawn to the erotic potential of androgyny. In A Farewell to Arms, Frederic and Catherine discuss growing their hair to the same length so that they can be “the same one.” In the story “The Last Good Country,” Nick Adams’s sister cuts her hair off so she can be like him—“I’m a boy, too”—and Nick says, “I like it very much.” But The Garden of Eden took all of this much further. Catherine cuts her hair to match that of her husband David but she then becomes a boy, Peter, and David becomes a girl, also called Catherine. David/Catherine is penetrated by his wife/husband:

He lay there and felt something and then her hand holding him and searching lower and he helped with his hands and then lay back in the dark and did not think at all and only felt the weight and strangeness inside and she said, “Now you can’t tell who is who can you?”

Zelda Fitzgerald’s mockery of Hemingway as “a pansy with hair on his chest” was crude and inaccurate but no more so than Hemingway’s own self-caricature as the straightest hombre on the planet.

Mary Dearborn’s well-balanced and deeply researched new biography convincingly traces some of this interest back to Hemingway’s childhood and the way his formidable mother Grace insisted on treating Ernest and his older sister Marcelline as if they were twins, giving them the same haircuts and insisting that they be in the same classes at school. The strong antipathy that Ernest developed for Marcelline may be the first expression of his tendency to react to complicated desires by swinging to the opposite extremes.

Advertisement

But Hemingway’s sexual complexity may also be connected to his experience in World War I. Of course, he hated the idea that he was traumatized. In part, he hated it because it was a cliché. There is weariness as well as humor in the deadpan way the narrator of The Sun Also Rises, Jake Barnes, says of his first meeting with Brett Ashley: “We would probably have gone on and discussed the war and agreed that it was in reality a calamity for civilization, and perhaps would have been better avoided.” It is understandable that Hemingway, whose family was cursed through the generations by mental illness and suicide, did not wish to be reduced to a case study. In the 1954 interview with Time, he asked, “How would you like it if someone said that everything you’ve done in your life was done because of some trauma? I don’t want to go down as the Legs Diamond of Letters.” (Diamond was a gangster known for surviving multiple shootings.)

When Philip Young’s study of him appeared in 1959, Hemingway objected in a letter to Harvey Breit: “P. Young: It’s all trauma. Sure plenty trauma in 1918 but symptoms absent by 1928.” But if the exaggerated masculinity was an attempt to escape Hemingway’s attraction to androgyny, the exaggerated action-man poses, the constant return to sites of death and danger, were surely symptoms of the long reach of his early wartime experiences.

Hemingway was just eighteen—in our terms barely out of his childhood—when he arrived in Italy in June 1918. On his first day there, before he had even joined his Red Cross ambulance unit, he was called to the scene of a huge explosion at a munitions factory twelve miles outside Milan. His first taste of war was collecting the shredded parts of the workers’ bodies. Hutchisson quotes from the diary of one of Hemingway’s comrades, Milford Baker:

In the barbed wire fence enclosing the grounds and 300 yards from the factory were hung pieces of meat, chunks of heads, arms, legs, backs, hair and whole torsos. We grabbed a stretcher and started to pick up the fragments. The first we saw was the body of a woman, legs gone, head gone, intestines strung out. Hemmie and I nearly passed out cold but gritted our teeth and laid the thing on the stretcher….

Dearborn, rather startlingly, gives this incident a single paragraph in her hefty biography, and confines her commentary to the breathtakingly glib: “Ernest went at the job most likely with his heart in his mouth.” It seems more likely that a kid who had never seen violent death before, let alone picked up a torso with dangling intestines, and who “nearly passed out cold” at the sight, was profoundly affected.

When Hemingway used this experience, in the story/essay “A Natural History of the Dead,” he did so within a frame of exaggerated scientific objectivity. The story begins: “It has always seemed to me that the war has been omitted as a field for the observations of the naturalist.” The passage dealing with the incident moves quickly from “I” to “we” and says nothing about almost passing out. It attempts a cold, neutral tone:

I remember that after we had searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments. Many of these were detached from a heavy, barbed-wire fence which had surrounded the position of the factory and from the still existent portions of which we picked many of these detached bits….

It is worth noting the (unconscious?) repetition of “detached”—the first time in the passive voice to distance us from the action of Hemingway and his colleagues actually picking body parts from the barbed wire, the second to distance those “bits” from the humanity to which they so recently belonged. There is something unconvincing in the prose, something panicked in the need for so much insulation from the reality being described. And that distancing becomes downright demented when Hemingway goes on to write, with a surreal blitheness, that “the pleasant, though dusty, ride through the beautiful Lombard countryside…was a compensation for the unpleasantness of the duty.” This takes protesting too much to a riotous pitch. When, in an early draft of the story published in Seán Hemingway’s new edition, his grandfather writes, “As for thinking about what I had seen; I have never been much impressed by horrors so called,” it is simply very hard to believe him.

Yet what is also very striking about the account in “A Natural History of the Dead” is that it strangely prefigures his interest in hair as a token of sexual inversion:

Regarding the sex of the dead it is a fact that one becomes so accustomed to the sight of all the dead being men that the sight of a dead woman is quite shocking. I first saw inversion of the usual sex of the dead after the explosion of a munition factory which had been situated in the countryside near Milan…. I must admit, frankly, the shock it was to find that these dead were women rather than men. In those days women had not yet commenced to wear their hair cut short, as they did later for several years in Europe and America, and the most disturbing thing, perhaps because it was the most unaccustomed, was the presence and, even more disturbing, the occasional absence of this long hair.

Here we can see Hemingway’s secret erotic interests—the inversion of gender, the fetishizing of hair—becoming entangled with extreme violence and grotesque horror. We do not have to reduce all of his life to trauma to understand how powerful the disturbance must have been for a teenager. It is hardly surprising that Hemingway’s career as a childish liar began after this psychological wound was compounded by a real one in July 1918 when he was hit by shrapnel and machine-gun fire. He began to tell tales of phoney heroics and he never really stopped. When the boasting was not enough, he threw himself into reckless adventures, going on safari, becoming (illegally) a combatant in World War II, and accumulating more and more of the brain injuries that surely hastened his descent into mania.

Oddly, the bragging sometimes obscured realities that were remarkable enough in themselves: while Dearborn, for example, dismisses Hemingway’s wartime links with the NKVD, forerunner of the KGB (“The NKVD connection never really bore fruit”), Nicholas Reynolds’s fascinating new research in Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy shows that he was in fact working for both the Russians and the Americans: he visited the Chinese Communist Party deputy leader for the NKVD on a reporting trip to China in 1940 even though two years later he was producing fantastical reports for the FBI on German spies in Cuba. (In one, he suggested using jai alai players to throw bombs into U-boats.)

Hemingway saw enough action not to have to make risible claims like his more-or-less single-handed taking of Paris from the Nazis, as Man’s Magazine had it in a 1959 spread entitled “Ernest Hemingway’s Private War with Adolf Hitler”: “When the Allies first marched into Paris, they found a sign reading ‘PROPERTY OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY.’” The truth that is most obscured by the puerile bravado, though, is the tenderness of Hemingway’s best fiction, its subversion of all those notions of heroic masculinity. In his sad little book, Papa: A Personal Memoir, Hemingway’s son Gregory, who was transsexual, wrote: “What I really wanted to be was a Hemingway hero. But what the hell was a Hemingway hero?… A Hemingway hero was Hemingway himself.” In this he was mistaken. The Hemingway hero, at least in his most important work, is very far from the hairy-chested ultra-male that his father pretended to be.

In one of his finest stories, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” the Hemingwayesque great white hunter Wilson is not the hero. The hero, Macomber, is a coward and a cuckold. In The Sun Also Rises, the central character Jake has no penis. And this is not, as it would have been in any novel before Hemingway, a symbol or a joke—it is a human reality evoked with gentle subtlety and infused with a simple dignity. Hemingway’s introduction of the fact is one of the great episodes of artistic tact. In the third chapter, the prostitute Georgette says, “‘It’s a shame you’re sick. We get on well. What’s the matter with you, anyway?’ ‘I got hurt in the war,’ I said.” In the next chapter, Jake is undressing and looks at himself in the mirror. Hemingway’s genius is to reveal Jake’s “hurt” to us while the narrator is also thinking about the furniture, so that what he sees in his reflection—his mutilated self—is mixed up with banal thoughts on the mirror in which he is seeing it:

Undressing, I looked at myself in the mirror of the big armoire beside the bed. That was a typically French way to furnish a room. Practical, too, I suppose. Of all the ways to be wounded. I suppose it was funny. I put on my pajamas and got into bed.

The rhythm of the prose here comes from Leopold Bloom, but Hemingway is going even further than Joyce did with Bloom in making the unmanned man a living and unashamed presence in literature. Jake recalls an Italian officer telling him that he has sacrificed more than life to the cause in losing his penis—but the book tells us that life, after all, is more than a penis.

This embrace of unmanliness extends, in A Farewell to Arms, to the ultimate betrayal of male honor, desertion from the warfront. Arguably the single greatest passage in Hemingway is about running away from war. The long description of the Italian army’s retreat from its disastrous defeat at Caporetto is a bravura set piece in itself and it is worth noting that for all Hemingway’s exaltation of true firsthand experience it was constructed from other people’s testimonies. It is also a farewell to valor and power and a manliness that expresses itself with a stiff upper lip. The carabinieri who question the retreating soldiers and summarily execute those they suspect of treason are models of coolness and courage, rendering those qualities appalling. That word “detachment” returns with all its psychotic resonance:

So far they had shot every one they had questioned. The questioners had that beautiful detachment and devotion to stern justice of men dealing in death without being in any danger of it.

And the hero of the book is literally fleeing from this beautiful detachment of the cool killer. He makes a break for it, both physically and psychologically: “I was through. I wish them all the luck…. But it was not my show any more.”

In these great books, Hemingway made his own break for it. And he nearly made it too. Aesthetically at least, manliness wasn’t his show anymore. Or at least it wasn’t until the world became enormously interested, not in his grown-up truths, but in his childish lies. He ran away from his own brave desertion. He became a male impersonator—the swagger, the drinking, the trading in of wives for younger models, the boy’s own adventures, the male harem of cronies, the exaggerated gestures of butchness became Hemingway and he became them. Having so heroically left the show, he ended up making a mock-heroic show of himself.

This Issue

June 22, 2017

Louis Kahn’s Mystic Monumentality

The Abortion Battlefield

-

*

David M. Earle, All Man!: Hemingway, 1950s Men’s Magazines, and the Masculine Persona (Kent State University Press, 2009). ↩