In the latter part of the 1820s, the novelist James Fenimore Cooper was in Paris, observing French society and meditating on the lessons to be learned from it by the United States. In one surprising segue from his book Gleanings in Europe: France (1837), he recommends the expenditure of thirty or forty million dollars on a navy to secure “our national rights” and, in the same sentence,

to appropriate, at once, a million to the formation of a National Gallery, in which copies of the antique, antiques themselves, pictures, bronzes, arabesques, and other models of true taste, might be collected, before which the young aspirants for fame might study, and with which become imbued, as the preliminary step to an infusion of their merits into society.

He was quick off the mark, in one sense, for Britain had opened its own National Gallery only a couple of years before. Otherwise, though, he was well ahead of his time, for the kind of comprehensive museum he described, with its mission to improve taste in the fine arts as a way of promoting better manufacturing, closely resembled what was launched in London in 1852 as the Museum of Manufactures, becoming eventually the much-imitated Victoria and Albert Museum. Cooper had looked at French manufacturing and seen a profound influence of the arts of design on everything from bronzes to ribbons and chintz. America needed to cultivate the fine arts:

Of what avails our beautiful glass, unless we know how to cut it; or of what great advantage, in the strife of industry, will be even the skilful glass-cutter, should he not also be the tasteful glass-cutter…. We beat all nations in the fabrication of common unstamped cottons…. But the moment we attempt to print, or to meddle with that part of the business which requires taste, we find ourselves inferior to the Europeans, whose forms we are compelled to imitate, and of course to receive when no longer novel, and whose hues defy our art.

It is easy to forget that this desire to improve the nation’s taste, and to apply lessons learned from the arts of the ancien régime directly to modern manufacturing, provided the motivation for the American interest in French painting. Cooper would have been gratified, had he been able to visit the Metropolitan Museum around 1910, to see precisely the kind of objects he had in mind (French eighteenth-century window bolts, keyhole escutcheons, faucets and furniture mounts in gilded bronze) on display with furniture and paneling and other forms of architectural salvage. “The rediscovery of the art of the different ‘Louis,’” wrote the art historian Bruno Pons, “occurred in the USA in a comprehensive manner, painting at the same time as sculpture, architecture at the same time as furniture and objets d’art.”

This is all the more striking when one considers how profound an antipathy there must have been for the licentiousness and perceived frivolity of, say, Boucher or Fragonard and their patrons. Pons quoted Fiske Kimball, the great authority on rococo art, to this effect:

In America the French art of the old regime has suffered from a prejudice—even from many prejudices. To the puritan and the Quaker the very word French evoked a furtive shudder. To the professional evangelist, setting down the cathedral builders as deluded Papists, and thinking of Voltaire and Rousseau, it connoted atheism and impiety. By the professional Anglo-Saxon, maintaining contrary to truth that the French have no word for “home,” French styles were conceived as formal and inhospitable. By the professional patriot and democrat the old French monarchy was conceived as the antithesis of liberty.

After this, open The Decoration of Houses (1897) by Edith Wharton and the architect Ogden Codman Jr. at almost any page, and you will find praise for the good sense and taste of the French under Louis XV–XVI, who, far from suffering a formal and inhospitable style, are promoted as having invented the first truly comfortable furniture and interiors. Clients of the exacting Codman with plans to build homes on Fifth Avenue or at Newport, Rhode Island, might meet up with their architect in Paris to be shown all the elements of their future interior. When Ethel Rhinelander King, widow of the eldest son of a family whose fortune came from tea, silk, and real estate, needed a drawing room in New York in 1900, the Paris firm of Audrain

shipped the boiseries, cornice moldings, parquet floor, bolts of yellow silk damask to be hung inside the wood panels (plus curtains and lambrequins with their requisite passementeries, bergères, fauteuils, various sizes of tables, a chandelier, wall sconces, Savonnerie carpet, and marble chimneypiece).

For all this, one had to wait. Even Ethel Rhinelander King would have had to wait for the arrival from Paris of a contremaître, or foreman, also supplied by Audrain, who would come to supervise the installation of the room.

Advertisement

In this period, the taste for eighteenth-century French painting—now such a well-established category in the history of art—was fairly recently developed. One would not expect a visitor to Paris such as Cooper in the 1820s or 1830s to have had much opportunity to see and admire, say, Watteau or Chardin or Fragonard. The grand private houses of Paris that, before the Revolution, had thrown open their doors to visitors were now accessible mostly to a circle of close friends.

As for the painters of the ancien régime, many of them were quite simply despised. The drawing students in the Louvre supposedly used Watteau’s Embarkation for Cythera for target practice with bread pellets. What they abused under the name “rococo” was the style of the era of Louis XV and XVI—in painting the style of Watteau and Fragonard. What they supported was the style we associate with Jacques-Louis David in painting and Canova in sculpture, what we now call “neoclassicism” but they referred to as the “true” or “correct” style.

In the middle to later years of the century, that situation was beginning to change through the efforts of private French collectors of no great means, but with enough discerning enthusiasm and patience to comb through the junk shops and the portfolios of the dealers. This was the tenebrous world of Daumier’s gaunt connoisseurs. This was the world of the Goncourt brothers, powerfully evoked in the catalog of the exhibition “America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting” at Washington’s National Gallery by a photograph of Edmond de Goncourt at home, with his books and his drawings and documents neatly sorted and tied up with ribbons. It was the world of Louis La Caze, whose enormous bequest of 583 paintings to the Louvre in 1869 included many eighteenth-century works, among them Watteau’s Pierrot (Gilles). And it was the world in which Baudelaire included Watteau among his “guiding lights,” or phares, in a poem which names a select list of the great.

The American experience of eighteenth-century French paintings could hardly have gotten off to a more distinguished start: in 1815, Joseph Bonaparte, elder brother of Napoleon, former king of Naples and Sicily, also former king of Spain, arrived in New York with his art collection and a library of six thousand books. In due course Joseph settled at an estate called Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey, where he took pleasure in making his paintings available both to visitors to his home and as loans to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Among works of family and military interest, there were also the spoils of his sojourn in Spain and grand French mythological paintings of an erotic bent: Charles-Joseph Natoire’s The Toilet of Psyche and Noël-Nicolas Coypel’s The Abduction of Europa (see illustration on page 31). In his catalog essay on the Joseph Bonaparte collection, D. Dodge Thompson quotes a contemporary account, by “two respectable Quaker ladies,” of being shown around Point Breeze by the Count of Survilliers, as Joseph called himself:

The walls were covered with oil paintings, principally of young females, with less clothing than their originals would have found agreeable in our cold climate, and much less than we found agreeable when the count without ceremony led us in from of them, and enumerated the beauties of the painting with the air of an accomplished amateur.

The Coypel alone, a riot of nudity, would have tested the broadmindedness of the visitors. It was followed by Canova’s seminude marble statue of Joseph’s sister, Paolina Borghese, and Titian’s violent rape scene Tarquin and Lucretia. The women were “visibly discomfited.”

In due course Joseph returned to Europe, but he gave the Coypel to his friend General Thomas Cadwalader, with whose family it remained until 1978, when it was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art “with the kind assistance of John Cadwalader, Jr.”—an impressive link across the centuries. But for evidence of direct artistic influence of Joseph’s collection on American artists, one must turn to the marine paintings of Claude-Joseph Vernet and to the portraits of Jacques-Louis David, including the latter’s equestrian portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps, whose fame had been spread by means of engravings.

The Washington show brings together sixty-eight paintings from forty-eight public collections in the US. This means that the net is spread wide, and you would have to be extremely well traveled to be acquainted with everything that is on offer. It would be fair to say that there isn’t a weak painting on view, but not every artist is represented as fully as his or her stature deserves. The single Watteau, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s The Perfect Accord, is beautiful and has been much copied over the years. Perhaps it is merely conventional to feel that there might have been a companion or two.

Advertisement

Similarly, the lone David, a portrait of Jacques-François Desmaisons from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, though attractive, is hard put to represent all that David means, and the catalog reproduces two works from the Met alone that one imagines must at some stage have been on the wish list for the exhibition—the great double portrait of Lavoisier and his wife, and The Death of Socrates. On the other hand, the National Gallery has been able to place its own great Boucher, The Birth of Venus, beside its companion piece from the Met, The Toilette of Venus, bringing the two works from the Marquise de Pompadour’s appartement des bains (her bathroom) back together. Boucher and Fragonard are the favored sons of the show.

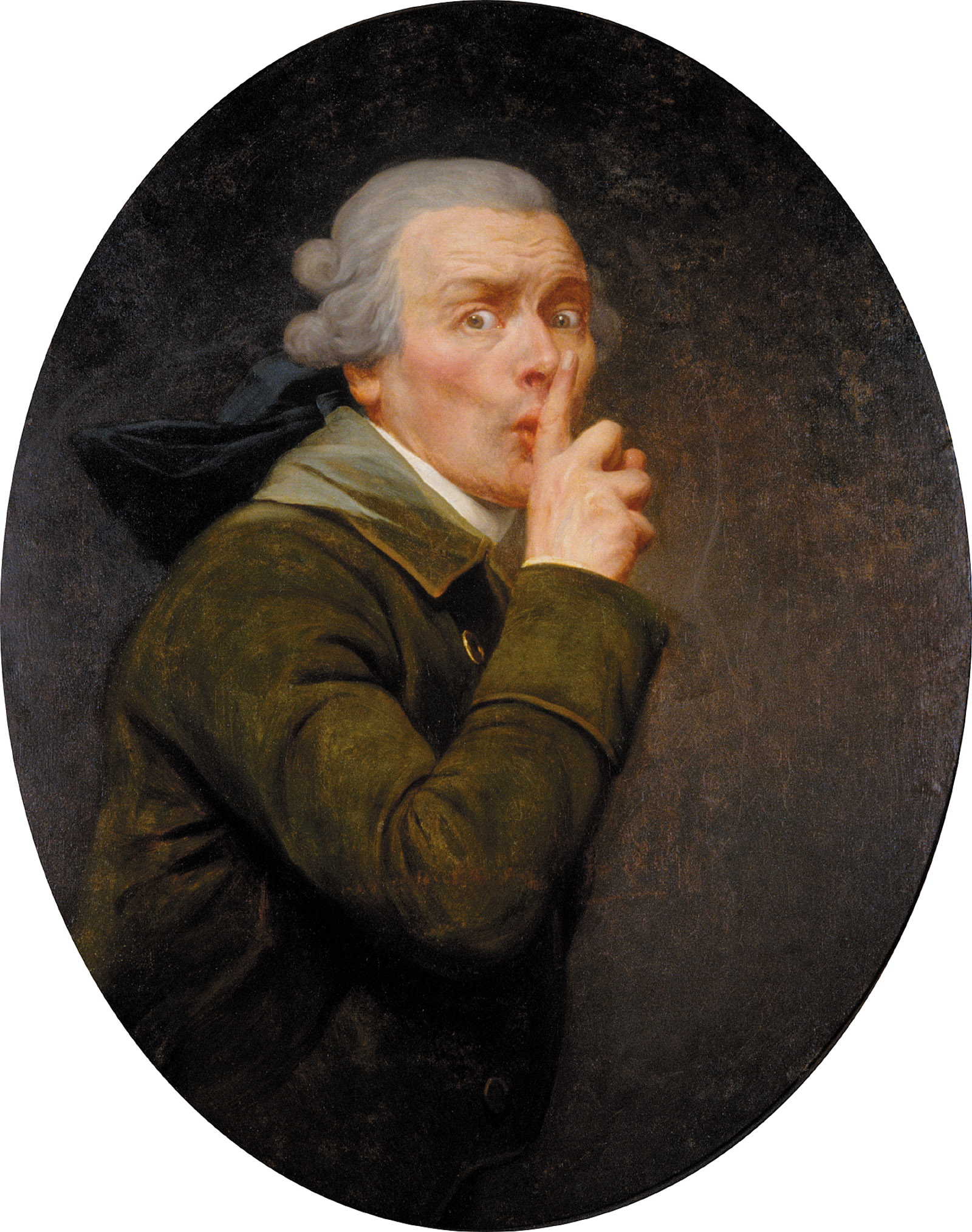

One of the great curiosities on view is Joseph Ducreux’s Le Discret, a self-portrait in which the artist raises a finger to his lips, urging silence. This comes from the Spencer Museum of Art, the former University of Kansas Museum. As Susan Earle informs us in her catalog essay, Ducreux had been first painter to the queen, Marie-Antoinette, until the Revolution. There followed a period in which, presumably short of sitters, he produced a series of self-portraits showing himself “laughing, crying, pointing derisively, or yawning.” This last mentioned—in which the artist yawns and stretches—is in the Getty. It is the only other painting by Ducreux in an American museum, and, like the Kansas work, the image is also known through prints.

These works appear to be, in painting, the equivalent of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s in sculpture—bravura exercises in physiognomy (but perhaps without the hint of lunacy in Messerschmidt). Ducreux himself called them “paintings of character which prove that certain painters of portraits can paint history.” No doubt that was the original impetus. One would dearly like to see the whole series, as one can see almost the whole Messerschmidt series in Vienna. For they seem to establish an intimacy and privacy, almost, that have wandered very far from the painting of history.

The catalog tells us something about the young museum director, fresh from his Ph.D. at Harvard, who made this unusual purchase in 1951 for $600. His name was John Maxon (1916–1977), and he was clearly a gifted purchaser of works of art—he bought a limewood sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider the next year. But the catalog does not tell us whether he was responsible for transferring the painting from its original canvas to an aluminum panel, thereby ironing it flat—a process once in vogue but now much deplored among conservators.

One of the guiding pursuits of collectors of French art was the search for items with a royal connection, including preeminently a connection to royal mistresses. A portrait by François-Hubert Drouais, sold by the firm of Wildenstein as Madame du Barry Playing the Guitar, turns out to have had the wrong gender assigned to it and is nowadays firmly identified as Portrait of Carlos Fernando FitzJames-Stuart, Marquess of Jamaica. It says something about Drouais’s sweetly ambiguous (and repetitive) physiognomies that the future duke could so long have been mistaken for a royal mistress. The painting hung in the fourteen-room Park Avenue apartment of Eugenia Woodward Hitt, shown in a photograph from 1991 with its mirrored interior and rich French furnishings. Mrs. Hitt, it appears, was the kind of art collector who knows when to stop: she stopped when she ran out of space. On her death in 1990, she bequeathed to the Birmingham Museum of Art (Birmingham being her home town) the contents of her apartment, amounting to some five hundred objects. Two of the Drouais paintings in the show come from this bequest.

In “Buying against the Grain: American Collections and French Neoclassical Paintings,” Philippe Bordes reminds us of the slow process by which David’s reputation, and those of his many students, were revived and redefined. The nineteenth-century charge that his work was frigid was hard to refute, particularly as so many of the artist’s works were languishing in neglect. Then, around the time of World War I, “paintings began to cross the Atlantic embellished by an attribution to [David], this most famous painter of his day.” Edward Julius Berwind paid a surprising $228,000 for what was described by René Gimpel, the dealer, as the most beautiful David in the world.

It was not by David, but by his pupil Marie-Guillemine Benoist; it is a portrait of Madame Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont and her son (now in the Met). But the attribution of a tender and charming depiction of motherhood to the supposedly frigid David acted as a kind of rebuttal. Here is a passage from 1919 in appreciation of this misattributed work:

The figure has a purity of line which recalls Greek art, but Greek art recreated in the flesh and spirit by a lover of form. When you compare this accomplished work with the formless and manneristic English portraits of the same period you do not hesitate to rank David as the greatest master of plastic beauty. Its altogether feminine seduction, the silvery radiation which issues from its exquisite flesh tones, the suppleness and abandon of the pose, combine to make a really picturesque masterpiece, stripped of all pedantry. This portrait is among the highest expressions of French art. How many such examples of discipline and free effusion are there to recompense us in our own troubled epoch?

Feminine seduction, not male frigidity. Greek, yes, but Greek art recreated in flesh, not marble. Discipline, yes, but then suppleness and abandon. The remarks to the detriment of English portraiture are carefully chosen to undermine one of the great genres of trophy art of the time. The whole passage can be seen as a plea to the lover of the rococo: contrary to what you may have been told, it says, you can love David and the rococo, too. And what was meant by David, in this context, seems to have been any neoclassical portrait of a pretty young girl in white, with a high waistband. But still it had to be conceded that there was another side to David, seen in his earlier work:

If we analyze the first revelations of this Master, we will find them academic, scholastic, but sustained by a creative strength which is never abandoned. There is, in the effort that dominates his work, something of fierceness which attains to a stoical power, power which is conserved by the reading of Plutarch, or the study of the Romulus or the Brutus of antique statuary.

Academic, yes, but fierce. Scholastic, yes, but sustained by creative strength. Roman indeed—who could deny it?—but this half-imagined David is a fierce Roman on the verge of transforming himself into a sensuous, feminine Greek.

In 1931 the curator Bryson Burroughs was at pains to persuade the Met to buy, for $18,000 (later reduced), one of David’s most famous compositions, The Death of Socrates. David, he wrote,

is recognized as the first of the modern school and as the founder of modern art. No artist since the Renaissance has had so lasting an effect as David has had; indeed his influence survives today. A long-lasting influence is a tangible proof of greatness, as far as an historical collection like ours is concerned. This picture is one of his most famous works, the only one of his great compositions, as far as I know, which remains still in private hands…. These elaborate compositions of his are not widely appreciated today, which accounts for the low price of the Socrates, whereas his portraits which he himself regarded as mere pastimes, are eagerly sought after.

The first of the modern school! The founder of modern art! Claims no doubt carefully crafted to assuage some tendency among the trustees, even if they leave us a little puzzled today. (Puzzled perhaps because Burroughs is quoting in the 1930s a remark made by Delacroix in the 1860s—as if nothing in the world had changed in the interim.) The curator anticipated a hostile public response, but he had well defined his “tangible proof of greatness.” And it is interesting to see, from Bordes’s account, how much further work had to be done simply to define David’s oeuvre and to weed out, or accurately reassign, many optimistic attributions. We are reminded too that the style known as “classical revival” was soon to be called “neoclassicism” on the publication in 1940 of Gusto Neoclassico by Mario Praz.

Rococo. Neoclassicism. The modern school. What a difference such words make to the way we can be persuaded to see.