The first time I visited Japan I fell hard for the highly abstract, ritualized form of musical drama called Noh. My Japanese friends found this a little puzzling, since I couldn’t understand the dialogue, and there was no simultaneous translation such as one finds at the opera. Even they didn’t understand the arcane Japanese dialect from hundreds of years earlier. There were synopses of the plays, of course—usually just a few lines in a mimeographed program. My traveling companion and I were often the only Westerners at these performances, which were held in the late afternoon, adding to the oddness of the experience. The atmosphere was very different from the more popular Kabuki. No beer. No cheering, no talking in the house at all. Pretty soon, as the intricate rhythms and the rising and falling pitch of the atonal chanting start to work on your brain, you begin to get a feeling for the dramatic arcs.

Memory plays. Ghost stories.

Noh is the carrying forward of misfortune, of a stain of disgrace that won’t go away; fate unwinds in front of you. Most of the action takes place before the play begins. Characters speak from beyond the grave, recounting memories of betrayal, luckless love, suicide by drowning. (George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo is American Noh.) The clacking together of two wooden blocks signals a change of scene and releases a heavy sense of malaise into the present. Visitations from the underworld are routine. The weeping cherry tree on a bare stage turns out to be the tears shed by an abandoned lover waiting to tell her story.

What elevates these narratives of woe is the solemnity of their staging, which contributes to a feeling that the boundaries between past and present, human and spirit, have loosened or dissolved altogether. The slowed-down movement across an empty stage, the actors’ white masks, the plaintive chanting and its shattering rhythmic accompaniment, the even, undramatic lighting—the theatrical illusion is hard to account for, but after two or three hours’ immersion in the Noh world, I would begin to feel myself overtaken by an immeasurable sadness, with tears spilling down my face. Such exquisite perfection in the telling, so much suffering in the tale.

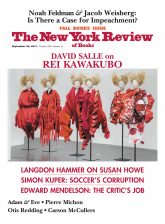

Walking mesmerized through the Rei Kawakubo retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum was the closest I’ve come since to the feeling of Noh theater. Without always understanding what I was looking at, I was gripped by the kind of melancholy that seems to accompany the toughest, most searching and demanding levels of beauty.

The exhibition design, a collaboration between Kawakubo and the Met curators, follows no perceptible chronology. Enclosures of various shapes—inverted cones, flattened spheres and semicircles, keyholes, ovals, triangles—contain the clothes, which are grouped by collection or theme. These frames are rendered in white plasterboard and lit from above by dense rows of fluorescent tubes, making a shadowless space, objective in tone. They are like viewing platforms, some of which function as small proscenium stages, while others are more like theater in the round. Still others are like caves whose restrictive openings give only a partial view of the clothes within. There is no attempt to make the clothes themselves look inhabited. Dresses and other garments are displayed on mannequin forms supported by thin metal rods, like sculpture. They are what Giacometti’s figures would be wearing had they taken the time to get dressed.

White muslin, bias-sutured Hans Bellmer dolls with steel wool hair, their bulbous silhouettes like Jean Arp cutouts.

Call it an alphabet/poncho. A dress that, seen from the front, is a near-perfect circle formed by a ten-inch-wide band of black velvet, the top of which thickens to form a cowl-neck that hides the wearer’s chin. The interior of the circle is a complex pattern of vertically striated pale beige lace, which is bisected in two places by horizontal tiers of contrasting ruffles. The arms do not protrude, but stay inside the circle, and the head is draped with black lace, mantilla style, so that the wearer appears as a walking “O” with a soft, furry center.

Black, aggressively ruched satin bomber jackets over wavy black panel skirts. One sleeve of the jacket has an extra-long extension that hangs down below the skirt, as if for an elephant’s trunk.

An antebellum-style dress with full and puckered cap sleeves, a low, scooped, and ruffled neck, and a skirt made of rows and tiers of short ruffles, all in a salmon-pink floral fabric, with brown and pale blue flowers. Sewn to its front and made out of the same fabric as the dress is a large stuffed bear, such as a child might carry, but with extra-long arms and an oversized snout, or maybe even a trunk, a bear becoming Babar; from another angle, the whole thing becomes a pink ruffled kangaroo.

Advertisement

Dome-shaped forms made out of gray-blue chenille, like an accumulation of upholstered headrests, gathered about the upper torso, shoulders, and neck; the meeting points of the heavily textured fabric recall the creased skin of a pachyderm. On top of this vertical Frank-Gehry-of-cloth is a “skirt” of shaggy black fake fur, which gives the whole composition ballast. Even though the dress falls to mid-calf, to wear it without the articulated black frou-frou would be like walking out of the house fully dressed but without pants.

Fruity shapes and silhouettes are everywhere. An apple perches on top of a pear; a kumquat floats above a doughnut peach; there are pumpkins, eggplants, and pomegranates, gourd shapes both rotund and hollowed out. Kawakubo is an Arcimboldo of cloth.

Some ensembles are reminiscent of the ecclesiastical raiments that you see in the store windows near the Pantheon in Rome. Loose-draped, knee-length robes in dark red floral brocade, the neck opening either a gathered cowl or a padded scoop, long loose sleeves that cover the hands. Now, using butch wax, pull the hair straight up and twist it into a point, so that it resembles a candle flame. Clothes made by a sorceress, for other sorceresses.

Who makes clothes like this? No one so flamboyant: the daughter of a university administrator, Kawakubo was born in Tokyo in 1942, studied the history of aesthetics at Keio University, did stints in advertising and as a freelance stylist before founding her own label, Comme des Garçons, in 1969, which has since grown into a large and profitable business. Its name—“Like the Boys”—was meant to signify the collaborative nature of the enterprise, and was fun to say. Her early clothes were monochrome—dark gray, white, and black—and drew on folkloric motifs.

In a lengthy interview with the Met curator Andrew Bolton that opens the catalog, Kawakubo, speaking through a translator, is adroit at not letting herself be drawn into generalities and disinclined to call herself an artist. “I make clothes,” she says simply. “I make objects for the body.” Whatever name she gives to her work, her clothes have the surprise, the emotional range, the formal imagination, and the gravitas—the authority—of art. To my mind, Kawakubo, supported by her creative team, has been working, for decades, at a level that most artists can only fantasize about.

What kind of artist is she? Let’s call her a combinatory formalist. She is unusually adept at combining the many disparate influences that course through her designs into unlikely, arresting, contrapuntal compositions. She is first of all a creator of images—of pictures liberated from their original settings, and in this she belongs with the Pictures Generation, that group of mediacentric artists who were among her first devotees.

Fashion is the place where the associative, imagistic mind can run riot with impunity; it’s a postmodernist playground. Part of it is practical: the need to come up with three or four or more collections a year, year after year, disempowers any will toward consistency. What makes a designer hold our attention over the long term is the contour and shape of her choices, and their integration into a larger philosophy of beauty.

A designer traffics in associations, and even the obvious ones in Kawakubo’s evolution are like a long, multicultural roller coaster ride through the history of style. They include, among others, Elizabethan court dress, the France of Versailles as well as the Belle Epoque, seventeenth- and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Japanese battle dress, and military clothing generally, as well as uniforms worn by Japanese workers in at least two other, more modern eras, 1980s punk and its appropriation of Scottish clan costumes, the wrapped and tied peasant clothes of India and Southeast Asia, African tribal headgear, medical prosthetic devices and restraining hardware, commedia dell’arte, children’s clothing from the era of Little Bo Peep, classical ballet, flamenco, and the Fellini of Juliet of the Spirits.

There are also numerous visual artists to whom her work invites comparison, from, most strikingly, Velázquez and Goya, to the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, and on to Dalí, Arp, Miró, Bellmer, and Magritte, as well as Calder and his “Circus”; to Lee Bontecou, Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, and Sheila Hicks (and fabric art in general), and then back to Rauschenberg’s Combines, and forward again to more recent work like the fabric sculptures of Georg Baselitz, Kara Walker’s spiky silhouettes, Rebecca Warren’s figures in squeezed clay and bronze, and the arresting animatrons by the current enfant terrible Jordan Wolfson.

Advertisement

And that’s just a partial list. Most of these names belong to the two movements in twentieth-century art history that seem to have most interested Kawakubo: Surrealism and Arte Povera—or Postminimalism—the latter with its emphasis on materials and process, and on the often mysterious energy that, as the late curator Harald Szeemann put it, emerges when “attitude becomes form.” Kawakubo’s achievement could be encapsulated as the combination of these two seemingly irreconcilable approaches.

All this list-making perhaps gives the wrong impression. Kawakubo is no appropriationist magpie. For one thing, she has made so many different kinds of clothes out of such a searching and diverse body of ideas that any one aesthetic position might be contradicted by the next year’s collection. The force of what she does with all these references and styles lies in her specific juxtapositions and recombinings. This is the stylist’s art taken to a whole new, one wants to say philosophical, level. In our time, juxtaposition itself has become the engine of art, or rather, where art’s inner energy becomes most visible. Kawakubo imbues the mixed metaphor with particular acidity and asperity. Never has pink-checked gingham, gathered and pulled tight over a nonanatomical protrusion, looked so uncompromising.

For this interplay of references to have real weight, there must be at least hints of a discernible visual syntax. How is it established, where does it reside? For Kawakubo, the answer lies in the relationship of image to form; it’s the relationship of the what to the how. Regardless of the imagistic valences, the starting point for her clothes is often the fabric itself, the material fact of it. A tightly bundled bodice or derriere takes on a different meaning if the bundling is accomplished with black crepe de chine or with red-and-green wool plaid. In this orchestration of her effects, Kawakubo has the design equivalent of perfect pitch.

“It requires more imagination to be a sculptor than it does to be a painter,” wrote the painter and critic Fairfield Porter. A painter can find the form, and subsequently the image, at the end of a brush. She may noodle around until eventually she finds something on the canvas that has vitality, but a sculptor must have more of an idea of where the work is headed, and she must master an often recalcitrant material to give shape to it. Whether the work is made by subtraction (cutting, chiseling, carving, etc.) or by addition (welding, sewing, stacking, binding, or just affixing a stuffed animal to a low brick pilaster), the sculptor at every turn must deal with an obdurate material reality. In Kawakubo’s work, the final image derives in large part from research into what materials can be made to do.

In the mid- and late 1960s, turning further away from representation, Postminimalism intensified art’s focus on process, on the act of making, that was begun by the Abstract Expressionists, but without the melodrama. Draping, wrapping, clustering, layering, stacking, scattering, and scaffolding—all the verbs of Postminimalist sculpture have their counterparts in the techniques of the needle trades. And if the traditional methods couldn’t give Kawakubo the effects she was after, new ones were invented. The clothes are not just radical looking, they are radically constructed, and some of the detailing and finishing that you can see up close in the more extravagantly shaped garments give an appreciation for just how complex and layered are the processes by which a form-in-cloth is made.

As a shape maker, Kawakubo starts with the body as an armature, an upright support on which to slash, mold, gather, and bind, the same as any designer, but she has in general steered clear of the tight-to-the-body mania that has dominated fashion over the last twenty-five years. One of her radical reimaginings is a “one size fits all” attitude toward body size that challenges the conventional idea of sexiness as a matter of display—showing more skin. Kawakubo is philosophically un-“size-ist,” and many of her clothes provide the wearer with a kind of open volume of fabric that takes different shapes depending on who’s inside.

Yet even when her dresses involve voluminous convexities that take up a lot of space, in the manner of traditional bell-shaped gowns, they are often conjoined with acts of restriction and compression: tying, binding, lacing, wrapping, or winding. She is interested in the redistribution or realignment of mass, and will sometimes use shapes to hold other shapes in place, or let one shape expand provocatively while corseting others, like squeezing your fist around the middle of a plastic bag full of Jell-O.

Or shapes are resolved by well-placed and artfully tied knots: straps, laces, strings, all pulled tight and tucked in. Much is made of the techniques of knot-tying, and the methods of wrapping up little parcels. Packaging, and the presentation of gifts generally, has long been elevated in Japan into a not-so-minor art form called tsutsumi, of which there are different schools and myriad forms. In Kawakubo’s version: take a crisp white bed sheet, throw in a big pile of bulky but soft-edged objects, gather the four corners of the sheet together, and tie them into a beautiful bow. Repeat six or eight or ten times, and place your parcels about the body: one on a shoulder, one at the hip, one on the collar bone, etc. Top off with a little black lace draped over the head. Voilà!

Especially in her earlier years, two foundational images have carried over from collection to collection, sometimes clearly delineated, at other times as more of a pentimento. The first image is of a bundle of cloth, such as a peasant farmer might carry hanging from a pole, now balanced on top of two sticks, or legs, like attenuated columns. A pile of hair, a twisting of cloth bags and sacks hung about the body: a modern vagabond. This is the folkloric, more overtly Japanese side of Kawakubo’s designs, and it recurs throughout her oeuvre in various guises. The other image, also folkloric, is the marionette. In this part of her vocabulary, the focus is on the hinge and the strap. Arms held akimbo, knees flexed, head tilted—the posture of the puppet, strings pulled taut or draped about the floor.

Unlike most of the major fashion brands, Kawakubo is not part of the cult of the model. There is no “face” of Comme des Garçons—and she is not dressing “the modern woman,” whoever that person might be. She exposes and directly challenges our ideas about beauty, and even coherence, as nothing more than culturally received attitudes. Many of her creations seem to stem from questions a child might ask: What would happen if…?, or Why not try…? A dress with four sleeves and multiple armholes? Jackets worn as pants, pants worn back to front—why not? This is art that says, “What, you only have two armholes? What a pity! Why should pants only fit your waistline? How boring!” Why should a dress be worn by only one person at a time? Why not wear two dresses at once? Why not cover your face in cellophane, or sew a giant stuffed toy onto your dress front, or attach big lumps to your shoulders and fanny, and pull your hair up into the shape of a candle flame? Why not??

Kawakubo says, “Nothing new can come out of a situation without suffering” and “There is very little creation without despair.” Some of her clothes from the last few years, the ones that feature arm-hiding, hobbling, and other movement restrictions, including more or less complete body-obscuring, call to mind the last scene from The Story of O, in which the heroine is totally submerged in her bird costume and paraded around on a leash. How can a sensibility and a work ethic that is so generous and unstinting also have a whiff of cruelty?

That’s one side. The other side of Kawakubo’s artistic nature is humorous and self-affirming, almost jaunty, expressed in collections with highly evocative, witty, and thought-provoking names like “Not Making Clothing,” “Body Meets Dress—Dress Meets Body,” and “Two Dimensions.” This side is expressed in clothes that come closest to traditional sportswear. Plaid jumpers, bright colors, tulle skirts, and knee-length cropped pants like hiking shorts—these are also signature looks. Kawakubo asks us to imagine a world in which Pauline Reage, author of The Story of O, companionably coexists with Claire McCardell, creator of American sportswear. Wait, you might say, that is our world.

Though there are many possible comparisons between Kawakubo and the art world, there are obvious differences in the ways that fashion and art are carried out. The biggest one is the coordinated talents of a large number of skilled artisans, the highest-level practitioners of the so-called needle arts. The process of turning ideas into clothes is intuitive, complex, and experimental, involving a seemingly magical translation on the part of the patterners, and Kawakubo has at her disposal an atelier full of cutters and shapers, finishers, sewers, and weavers, many of whom have worked with her for the duration of her career. Her chief patterner, Yoneko Kikuchi, who has become managing director of production, is quoted in the exhibition catalog: “It takes time exploring ideas in Kawakubo’s mind and giving them form…. It becomes crucial to have creativity from every one of us….”

The process at times resembles a game of “Guess what I’m thinking,” a kind of inspired charades-meets-zen-koan. Another patterner relates how Kawakubo once brought into the studio a crumpled piece of paper and directed the team to make something that had the same quality. It is truly a collaborative art, and such a group of co-creators would be the envy of many artists, myself included, but of course one must know what to do with such skilled people.

Kawakubo’s decades-long collaboration with her lead cutters and pattern-makers also says something about time and longevity in relation to an artist’s imagination. One of the revelations of the exhibition is just how many of the most original designs were made within the last five years—the ones least tethered to notions of taste or even functionality, in which the whole history of fashion seems to have been digested and reinvented as one mind-blowing dress after another, each completely different from the one before. It is among the most sustained sprints of creativity seen in any of the arts over the last fifty years.

There is a kind of art experience that seems to anticipate our reactions, and beyond that, our yearning for a certain kind of feeling, essentially one of being taken to a more rarified place. The art got there first, so to speak. Yes, we think, we didn’t realize it before, but this is what it feels like to be alive at this moment. It might be triggered by a surprising juxtaposition, a new use for an old material, combined with a harking back, a vestigial memory of a mostly lost classical past. The feeling is complicated; it can be gut-churning, because of what it demands of us, or piercing, as when attached to, say, a Rauschenberg Combine painting.

The sensation is even more unsettling when it’s produced by an article of clothing. A dress, a pair of pants, a smock—how much could they mean? Kawakubo’s clothes, especially for someone who has not closely followed her shows from season to season, instill a sense of coming late to the story, of being able to grasp only a piece or an outline. So much has already been decided before you got there. Once made, the decisions are somewhat familiar: they make use of elements one recognizes, and the logic of the materials themselves, but the sum of their effect when combined in one garment leaves you playing emotional and aesthetic catch-up.

Kawakubo named her most recent collection “Invisible Clothes,” an ironic or koan-like title. Get your mind around this, they say. Circling back to her original black and white, or just black, with white used as an accent or punctuation, these clothes have the severity of some of her earliest collections, but with the sublime and mysterious quality of the best art. One dress from that collection takes the shape of a giant, ragged-edged ravioli, rendered in matte-black quilted satin. Running vertically up the middle of this dark, glimmering pasta is a vertical dimple, two deep folds in the cloth that reveal the silhouette of a woman, flaring at the hips and narrowing at the waist, before ending in the inspired, perverse gesture of a vastly oversized, round-edged, brilliant white Peter Pan collar. The dress is shown in the catalog with the model’s face covered in what looks like Saran Wrap, with white ribbon tangled about the hairline—one of the many photographs by Paolo Roversi that made me gasp as I turned the pages. Its effect can’t really be explained, but it left me with a feeling of elation. Another piece from the collection resembles a cylindrical upholstered pumpkin. And yet another is a cross between Little Red Riding Hood and a beach chair with its own awning. No other designer has made clothes that come so close to a feeling of madness.

Kawakubo’s work embodies a potent wish-drama, the same one that has gripped virtually every avant-garde artist from Manet to the present: the wish to be radical, undermining, wholly original, and also to claim, somewhat miraculously, the unselfconsciously egotistical personality of the artist. The modern artist says, Love me for hating what you love, and love me for not needing you.

How could such an intense fashion theoretician with seemingly no particular desire to please have enjoyed such a success as a brand? She tells Bolton in the catalog interview: “It’s for others to interpret what I create.” “I’ve never liked my clothes being interpreted.” “Basically, I’ve never wanted my work to be understandable.” If there were ever any doubt that fashion designers are the true inheritors of the Surrealist legacy, that last statement is the kind of thing that could have been said, with perhaps a more sociable tone, by Luis Buñuel.

The exhibition’s nonlinear layout underscores the melancholy feeling that attaches to the clothes themselves. There’s a loneliness to them that stems from the isolating effect of high principles. As great domestic architecture can make most homes look careless and dull, these are clothes that make everything else we’re wearing seem mundane at best, unthought-out. Looking at her work, I’ve seldom felt such a strong sense of missed opportunity. Being confronted with such a novel idea of beauty pushes us past the point of detached amazement—it’s destabilizing.

There has been a certain amount of talk in the fashion press as well as by Kawakubo fans about how her clothes only really come alive when worn. Without disputing that obvious truism, it felt to me that many of Kawakubo’s shapes and forms seem to derive from an inner intensity that does not shirk even from the malevolent. I didn’t miss the human presence; there were plenty of ghosts in the room. The clothes are for people unlike us, but looking at them reminds us of memories and emotions that are so intense as to sometimes be painful, at which point the ghost-wearers become like us, but a little too late. Rather than celebrating the now and congratulating us on our modernity, this is work that wears the heaviness of time. Like Noh theater, like the best art, it implicates us emotionally while also leaving us behind. These are clothes that you may need, but they definitely do not need you.