Ambiguity has been an arresting feature of language ever since people learned to care about words for reasons unconnected with utility. An instruction manual on fixing a wheel shouldn’t leave you uncertain whether a wood or a metal spoke is preferred. But diplomacy can allow for “strategic ambiguity,” well understood by all parties, where too much specification would hamper an agreement.

Ambiguity in literature is a more elusive thing—not a matter of tacit meanings suppressed to secure a particular end. An ambiguous moment in a poem may indicate a suspension between two states of mind, in a situation where someone confined to either state could not know the reality of the other. It commonly turns on a hidden complexity that the reader is prompted to notice in a single word—for example, the word “honest” in Othello, as applied to the character of Iago. Or it may emerge from the cunning deployment of a genre like pastoral, which induces readers to reflect on themselves while looking at something apparently unlike themselves.

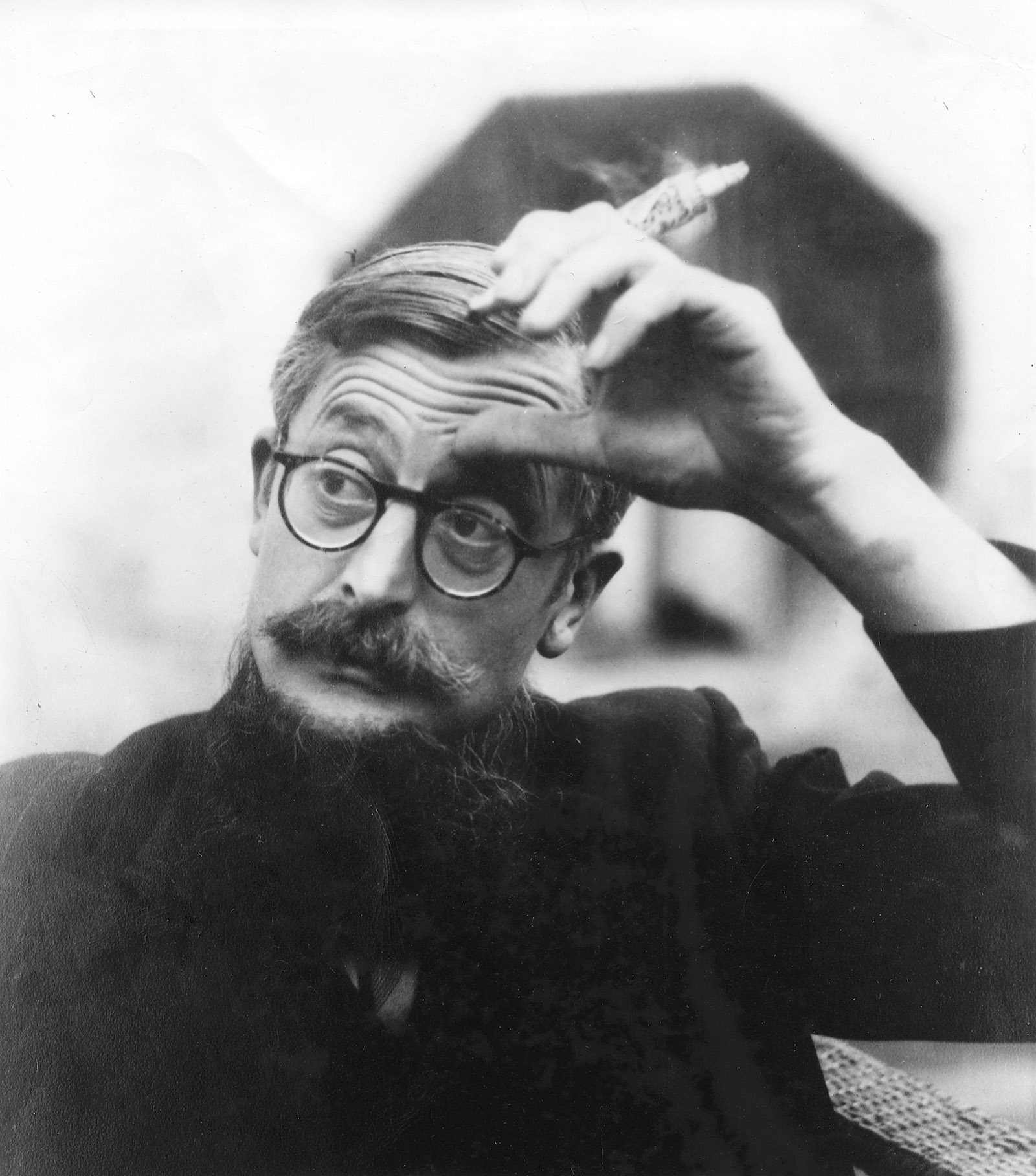

None of this would have seemed implausible or unfamiliar to Johnson, Coleridge, or Hazlitt, the great critics of the eighteenth and the nineteenth century. Yet the widespread practice of “close reading” was only settled in the mid-twentieth century; and its original genius and greatest practitioner was William Empson. His first three books, Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), Some Versions of Pastoral (1935), and The Structure of Complex Words (1951), all deal with motives and doubts of a sort that don’t declare themselves on the face of a work.

How recondite is this concern? Michael Wood in On Empson picks out a remarkable sentence from Seven Types to show the connection between ambiguity in action and in writing:

People, often, cannot have done both of two things, but they must have been in some way prepared to have done either; whichever they did, they will have still lingering in their minds the way they would have preserved their self-respect if they had acted differently; they are only to be understood by bearing both possibilities in mind.

The passage suggests a broader truth. Empson’s criticism is full of sympathy for human weakness and blindness, but this need not coincide with a high estimation of humanity. He thinks we are creatures who can’t fully know ourselves: there is a strong parallel here between Empson on ambiguity and Freud on the unconscious. Our reasons are never identical with our motives; the condition seems incurable. Still, we are right to want to understand its nature and manifestations.

Empson had a consistent aim as an educator. “The main purpose of reading imaginative literature,” he wrote in the Festschrift for his teacher I.A. Richards, “is to grasp a wide variety of experience, imagining people with codes and customs very unlike our own.” He said it another way in a generalizing passage of his only work of full-length commentary, Milton’s God (1961):

The central function of imaginative literature is to make you realize that other people act on moral convictions different from your own…. What is more, it has been thought from Aeschylus to Ibsen that a literary work may present a current moral problem, and to some extent alter the judgement of those who appreciate it by making them see the case as a whole.

To make the reader see the case as a whole, the author must have seen all around the subject. So if a work celebrates a heroic action, the judgment of those who appreciate it must be made to recognize the cost to the hero and his cause—especially the part of the cost they fail to understand. The Iliad does this for the martial valor and vanity that protract the sufferings of the Trojan War; so does Paradise Lost when it instructs readers in the ambiguous gift of a freedom achieved through transgression of God’s law.

Before he wrote his critical books, Empson had acquired a separate fame as an avant-garde poet—gaining admirers in later years from his appearance in a great many anthologies around midcentury—and though he stopped writing poems at thirty-four, his work in verse has an originality as pronounced as that of his criticism. Wood dedicates a chapter to interpreting poems in Empson’s early metaphysical manner; but even in his first book of poems, one may notice a congruence with the ethical aims of his criticism. “Homage to the British Museum” addresses—from a perspective of anthropological tolerance—the multiplicity of religious beliefs. The approach is generous and serenely skeptical; the gods appear, in this setting, as human creations, not lined up to pick out a single truth, but struggling differently and wrongly to satisfy all-too-human cravings:

There is a Supreme God in the ethnological section;

A hollow toad shape, faced with a blank shield.

He needs his belly to include the Pantheon,

Which is inserted through a hole behind.

At the navel, at the points formally stressed, at the organs of sense,

Lice glue themselves, dolls, local deities,

His smooth wood creeps with all the creeds of the world.

Attending there let us absorb the cultures of nations

And dissolve into our judgement all their codes.

Then, being clogged with a natural hesitation

(People are continually asking one the way out),

Let us stand here and admit that we have no road.

Being everything, let us admit that is to be something,

Or give ourselves the benefit of the doubt;

Let us offer our pinch of dust all to this God,

And grant his reign over the entire building.

“The world is everything that is the case,” wrote Wittgenstein, in an aphorism that Empson admired and variously echoed. This poem says that the knowledge of “all their codes” imparted by science is all we can claim to understand about the world. The gods are vapors emitted by our daydreams of order and omnipotence. In that sense, a “Supreme God” is ethnologically interesting; satisfactory for those who believe, and harmless to those who don’t.

Advertisement

Empson regards with a detachment bordering on contempt the part of human nature that would grant moral authority to a god; the poem, meanwhile, concedes the picturesqueness of theology, so long as it doesn’t get out of hand. But we are also being warned against the posture of superiority that an enlightened onlooker is apt to assume: “we have no road,” either, and our job as spectator-participants is simply to “attend”—as if religion were a theatrical performance or a medical operation. Accordingly we must offer “our pinch of dust,” the homage of our own unbelief, to this inadequate symbol of human aspiration that “creeps with all the creeds of the world.” Two of Empson’s later poems, “Sonnet” and “Manchouli,” are carriers of the same sentiment.

Anyone’s experience of reading poetry as difficult as Shakespeare’s or Milton’s or Hart Crane’s will show how intricate it can be to work out a basic sense of the words. An anxious shyness or frustration in the reader, or the academic wish for a “truth” that will satisfy the scientists, has sometimes led to the suggestion that this difficulty can be solved by referring to the author’s intention. Doesn’t the writer know best what his work really means? And can’t we find out what he wanted us to know? A theoretical rebuke to any such solution came from the argument of the New Critics of the 1940s and 1950s against “the intentional fallacy”: the work had a life of its own, they said, not dependent on the author, and neither a writer’s own testimony nor any amount of circumstantial evidence could claim automatic authority or exhaust the possibilities of interpretation. Empson agreed about the difficulty and inexhaustibility of great writing, but he thought that commentators who omitted all talk of intention had gone too far. They were excluding on principle a kind of knowledge their own experience and affections could have supplied.

Wood admires—from too careful a distance I think—the speculative freedom that Empson allowed himself in writing about the intentions of Shakespeare, George Herbert, and many other poets. The adventurous quality that sets him apart from other commentators seems hard to regret; if it makes him rash or unconsciously funny (as Wood now and then suspects), so much the worse for seriousness. Thus, in his late essay on Hamlet, Empson supports and elaborates the theory that Shakespeare was working from an “ur-Hamlet” with a stale revenge-plot he had somehow to breathe life into. Empson here takes his full swing:

He thought: “The only way to shut this hole is to make it big. I shall make Hamlet walk up to the audience and tell them, again and again, ‘I don’t know why I’m delaying any more than you do; the motivation of this play is just as blank to me as it is to you; but I can’t help it.’ What is more, I shall make it impossible for them to blame him. And then they daren’t laugh.”

There has never been a quicker insight into the conventional genre Shakespeare inherited and the tremendous change he wrought.

In Empson’s reading of Hamlet, as always in his criticism, a generous view of the entire work is built up from particulars. Consider Horatio’s uneasy comment when, in the fifth act, Hamlet reveals that he has procured the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: “So Guildenstern and Rosencrantz go to’t.” Empson remarks that “on this mild hint Hamlet becomes boisterously self-justifying”—Hamlet says, in fact, that these deaths “are not near my conscience,” and Horatio comments further, “Why, what a King is this!”

Advertisement

Now, exactly what work is that last line doing? In his reply to Horatio, Hamlet says:

Does it not, think’st thee, stand me now upon—

He that hath killed my king and whored my mother,

Popped in between th’election and my hopes,

Thrown out his angle for my proper life,

And with such coz’nage!—is’t not perfect conscience

To quit him with this arm?

Empson writes:

The repetition of “conscience,” I think, shows the gleaming eye of Shakespeare. Critics, so far as I have noticed, take Horatio’s remark to mean that Claudius is wicked to try to kill Hamlet, and this is perhaps what Hamlet thinks he meant; but I had always assumed, and still do, that he meant “what a King you have become.”

Hamlet, in short, has become a king indeed and a nasty one, quite comparable to Claudius.

Try this reading by the practical test—how would it play?—and Empson’s interpretation comes off markedly superior to the alternative; for Horatio’s tone here is subdued and ironic, whereas a reading that blamed Claudius would be redundantly reassuring to Hamlet—a piece of flattery out of key with Horatio’s temperament. Near the end of the essay, Empson decides that “the eventual question is whether you can put up with…Hamlet, a person who frequently appears in the modern world”; and he concludes, “I would always sympathize with anyone who says…that he can’t put up with Hamlet at all. But I am afraid it is within hail of the more painful question whether you can put up with yourself and the race of man.”

Some of Empson’s most inspired thinking went into his criticism of Shakespeare; and the essays on King Lear and Othello in The Structure of Complex Words show how thoroughly he favored reading over performance. But if the words are good enough, they want to be said in a certain way:

The thing most needed in Shakespeare productions…is that the actors should believe in their words sufficiently to say them; firmly and rather coolly, with rhythm and not much “poetry,” not burying them under the “acting,” not shuffling them off in the course of a walk round the stage with an air of having to take a swim through butter before the play can proceed.

And yet, some way in back of our reading we must discern an intention, a motive, a story under the story, or what an actor would call a subtext. In this sense, Empson’s criticism puts him forward as the most convincing imaginable interpreter of lines that the poet has supplied—whether the poetry is dramatic, epic, or lyric. If you are not saying it this way, he is telling his readers, you are getting the wrong feeling out of it, a weaker and thinner feeling, and somehow closer to cliché.

An extraordinary episode in Empson’s long career would emerge from his claim of just such unconditional authority. In the late 1940s, when he was teaching in China, he published a review of Rosemond Tuve’s Elizabethan and Metaphysical Imagery, a book he reports parenthetically having read alongside two books on Shakespeare’s rhetoric—“comforting things to have in bed with one while the guns fired over Peking.” Tuve argued that Empson had overrated the presence of ambiguity in Donne and other metaphysical poets; and in a later article, she supplied an orthodox reading of Herbert’s poem “The Sacrifice” to refute Empson’s idea that an image of Christ on the cross as a boy climbing a tree was a scandal for the Christian believer, a painful proof of the cruelty at the heart of the faith. The controversy went on for many years in public and private correspondence and reached a climax with Empson’s assertion:

I claim to know not only the traditional background of Herbert’s poem (roughly but well enough) but also what was going on in Herbert’s mind while he wrote it, without his knowledge and against his intention; and if [Tuve] says that I cannot know such things, I answer that that is what critics do, and that she too ought to have “la clef de cette parade sauvage.”

He was hardly more concessive in his disagreements with F.R. Leavis, Raymond Williams, C.S. Lewis, Frank Kermode, and Helen Gardner.

His interest in the probable motives of a writer—the “story” to be discerned behind the most condensed and impersonal of poems—led Empson into a uniquely perceptive train of thought on the anti-Semitic lines in the published draft of The Waste Land. “The young Eliot,” says Empson,

had a good deal of simple old St. Louis brashness; half the time, when the impressionable English were saying how wonderfully courageous and original he was to come out with some crashingly reactionary remark, he was just saying what any decent man would say back home in St. Louis—if he was well heeled and had a bit of culture…. [In The Waste Land] Eliot wanted to grouse about his father, and lambasted some imaginary Jews instead.

Empson goes on to say that Eliot’s grandfather “went to St. Louis as a missionary preaching Unitarianism”; that “Unitarians describe themselves as Christians but deny that Jesus was God”; and so the inference becomes clear:

Now if you are hating a purse-proud business man who denies that Jesus is God, into what stereotype does he best fit? He is a Jew, of course; and yet this would be a terrible blasphemy against his family and its racial pride, so much so that I doubt whether Eliot ever allowed himself to realise what he was doing. But he knows, in the poem, that everything has gone wrong with the eerie world to which the son is condemned.

An innocent reader might talk of what “the author is telling me”; an aesthete, purified of the author’s intentions, would perhaps want to say “the poem knows”; and the difference in Empson’s way of putting it is instructive. The poet, he says, “knows, in the poem.”

Empson’s three separate intervals of teaching in the Far East occurred from necessity as well as choice. Near the end of an undergraduate career with distinction in mathematics and English, he had been thrown out of Cambridge when condoms (“love engines”) were discovered in his rooms. Conventional employment closer to home became as unlikely as it was undesired. At the same time, his nature was congenial to life at the frontiers, where he could witness close-up a “heartening fact” about cultures remote from the English, namely “their appalling stubbornness.” From 1931 to 1934 he held positions at Tokyo University of Literature and Science and Tokyo Imperial University; from 1937 to 1939 in the makeshift universities of China under siege; and after returning to England during the war years, from 1947 to 1952 at Peking National University.

In London during the 1940s, he broadcast alongside his friend George Orwell for the BBC Overseas Service. “My second volume of verse The Gathering Storm,” he wrote in a letter, “means by the title just what Winston Churchill did when he stole it, the gradual sinister confusing approach to the Second World War.” And again in another letter: “I gave up writing for ten years because I really thought allied propaganda important.” When his colleagues and students in China had to adapt quickly to the military and political changes, Empson lent a hand where he could, and in a way that no one else could have done. As a witness of that period testified, what they chiefly required was books, and “Empson, without saying anything, typed out Shakespeare’s Othello from memory.”

It was in these years, too, that he composed the study of the Buddha’s faces, the manuscript of which was recovered after his death and has recently been published.* It is a work of comparative ethnology that is altogether compatible, as Wood takes care to notice, with Empson’s concern that we see two sides of a question or a complex state of mind in a speaker. The complex state, in this account, often appears in the two sides of the face of the Buddha. “It will be agreed,” Empson wrote in a draft digest of his theory, “that a good deal of the startling and compelling quality of these faces comes from their combining things that seem incompatible, especially a complete repose with an active power to help the worshipper.”

The strength of On Empson is to demonstrate by well-chosen quotations and commentary “the verve and provocation of Empson’s writing”; criticism and poetry are dealt with in separate sections, but Wood makes us aware that the mind at work is the same in both idioms; and his treatment of Empson’s essay “Honest in Othello” has a marvelous immediacy. Empson, says Wood, is writing here “about meanings that are very close to a word,” and Wood himself brings life to the strangest of imaginative conjectures, namely that a dubious word may “take the stage” and displace a character who has less reality than the stray and shifting words spoken by and about him.

It has been supposed by scholars who set a high value on cleverness that Empson cherished ambiguity and complex words for their own sake. The truth is that the struggle with words, for him, had a psychological dimension that went beyond any intellectual satisfaction. “The poem,” he said once in an interview, “is a kind of clinical object, done to prevent [the poet] from going mad”; and he said the same, in other words, in two of his best known poems, “Missing Dates” and “Let It Go.” One can imagine him agreeing with the last sentences of R.G. Collingwood’s Principles of Art, which speak of art as an almost medical remedy against “the corruption of consciousness.”

Empson’s own poems seek a resting place they know to be temporary, and they are written under immense pressure. “All losses haunt us,” he says in one poem: “It was a reprieve/Made Dostoevsky talk out queer and clear.” And his great poems all seem to be about loss. The most dryly intimate and commanding from start to finish are “Villanelle” and “Aubade”; but when Empson wrote about pain, “queer and clear,” it was often in an abstract idiom that held back almost every connective clue to personal experience.

“The Teasers” seems to share the existentialist mood of the time, as Empson later admitted somewhat ruefully, and its central argument and motive are plain enough. Our acts are governed, as if from a place beyond us, by a pattern or fate we can only dimly make out, and with which nonetheless we cannot fail to cooperate:

Not but they die, the teasers and the dreams,

Not but they die,

and tell the

careful flood

To give them what they clamour for and why.

You could not fancy where they rip to blood

You could not fancy

nor that mud

I have heard speak that will not cake or dry.

Our claims to act appear so small to these

Our claims to act

colder lunacies

That cheat the love, the moment, the small fact.

Make no escape because they flash and die,

Make no escape

build up your love,

Leave what you die for and be safe to die.

The ending is stoical: it is never “safe” to die, of course, and the flatness of the irony there is chilling. When once you have separated yourself from every cause, however, and given up the idea of escape, you are alone with whatever love you have built up and there is a kind of reprieve in that solitude. It is as true as Sartre’s aphorism “we are left alone, without excuse”—and perhaps less tinged by melodrama. The tenor of the poem is desolate, but the feeling is of an achieved equilibrium: nothing more needs to be said. And it may have been this undertone of his poetry that commended it to the Movement poets of the 1950s: Thom Gunn, Kingsley Amis, D.J. Enright. Philip Larkin’s clinching line in a characteristic poem, “Nothing, like something, happens anywhere,” could be a repeated line in a villanelle by Empson.

When I started reading him in 1968, Empson had written most of what he was going to write but had chosen to publish only four books of criticism and his Collected Poems. Thanks to the scholarly labors of his biographer John Haffenden, and the critical interest incited by Christopher Ricks, Paul Fry, Christopher Norris, and others, we now have fourteen books by my count—not including Haffenden’s edition of Selected Letters, Jim McCue’s chapbook of the brilliant undergraduate reviews he contributed to the Cambridge magazine Granta, and the finely made selection Coleridge’s Verse, edited by Empson and David Pirie, for which he wrote a major introductory essay.

If you want to know what critical writing in English can be, these make a large proportion of the short list of books you will want to have; and Wood’s On Empson offers the most fluent guidance imaginable to the genius and the ingenuity of the man. Candor in argument and a nervous susceptibility to shades of meaning are among the traits one encounters everywhere in his writing, but there is another quality he conveys without trying. One of the feelings you have when you read his criticism is elation. This is not a matter of a particular insight, observation, or epigram. It can last for pages.

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God

-

*

William Empson, The Face of the Buddha, edited by Rupert Arrowsmith (Oxford University Press, 2016). ↩