With its economic instability, mass immigration, corrupting influence of money on politics, and ever-increasing gap between the rich and everyone else, our current era bears more than a slight resemblance to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, dubbed by Mark Twain the Gilded Age. There are also striking differences. Back then, larger-than-life radical organizers—Eugene V. Debs, Emma Goldman, Bill Haywood, and others—traversed the country, calling on the working class to rise up against its oppressors. Today’s critics of the capitalist order such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren seem tame by comparison.

In her time, Lucy Parsons was as celebrated a radical orator as Debs and the others. Born a slave in Virginia in 1851, she lived into the 1940s, witnessing vast transformations in the American economic and political order but also the persistent exploitation of American workers. She became a prolific writer and speaker on behalf of anarchism, free speech, and labor organization. But she has been largely forgotten, or treated as an afterthought compared with her husband, Albert, an anarchist executed after Chicago’s Haymarket bombing of 1886. Thanks to Goddess of Anarchy, Jacqueline Jones’s new biography, readers finally have a penetrating account of Parsons’s long, remarkable life.

One of the most influential historians of her generation, Jones is the author of books that sweep across centuries. Her previous works include a pioneering history of black women’s labor in America, a study of the evolution of the underclass, an account of four centuries of black and white labor, and a history of “the myth of race” from the colonial era to the present. Again and again, Jones returns to the complex connections between racial and class inequality in American history.

Jones makes clear that Lucy Parsons deserves attention apart from her martyred husband. Originally named Lucia, she was removed with other slaves to Texas by her owner (probably also her father, Jones believes) during the Civil War to prevent them from seeking refuge with the Union army. Educated after becoming free at a school established by a northern teacher, she fell in love with Albert Parsons, the descendant of early New England settlers, whose father had moved to Alabama in the 1830s. (Parsons had fought on the Confederate side and managed to survive four years of bloody fighting.) During Reconstruction, when Congress rewrote laws and the Constitution to grant legal and political equality to the emancipated slaves, Parsons embraced these radical changes. He moved to Texas, where his brother ran a newspaper, and became one of the few white leaders of the state’s predominantly black Republican Party. (Most of the other white members in Texas were German immigrants who had remained loyal to the Union and suffered severe reprisals under the Confederacy.)

Parsons worked as a journalist, political operative, and officer of the state militia as it sought to put down violence against blacks. He emerged as a spellbinding speaker, addressing crowds of up to a thousand freedpeople. Reconstruction was a violent time, and nowhere as violent as in Texas, where armed bands committed many atrocities against former slaves and their allies. The life of a Republican leader was hardly secure, and became even more dangerous when Albert and Lucia wed in 1872—interracial marriages were frowned upon, to say the least, by white Texans. Albert was assaulted, shot at, and threatened with lynching.

Soon after white supremacist Democrats regained control of the state government in 1873, the couple left for Chicago. En route, in good American fashion, Lucia reinvented herself. She changed her name to Lucy and henceforth described her ancestry as Mexican and Indian (although on the birth certificate of her son, born in 1879, she identified his race as Negro). Passing for white has always been an option for light-skinned blacks. Lucy’s complexion made this impossible; she did, however, try to shed the stigma of slave origins. She and her husband never set foot in Texas again.

Chicago in the 1870s was home to a militant labor movement and the site of bread riots and mass strikes. Albert Parsons joined the small Socialistic Labor Party and picked up where he had left off as a public speaker, quickly making the transition from denouncing the southern planter class to assailing northern capitalists, and from condemning chattel slavery to demanding the abolition of wage slavery. “My enemies in the southern states consisted of those who oppressed the black slave,” he proclaimed. “My enemies in the North are among those who would perpetuate the slavery of the wage workers.”

During the national railroad strike of 1877, thousands of demonstrators clashed on Chicago’s streets with police and armed veterans’ organizations, leaving over thirty workers dead. Afterward, Parsons lost his job as a printer and was blacklisted; Lucy, an accomplished seamstress, supported the two of them by establishing a clothing shop. That same year, Parsons ran for local office as a socialist and did so for the next three years. But he received only a tiny number of votes. This lack of electoral success, combined with the labor militancy he witnessed in 1877, convinced him and his wife that violent upheaval, not the ballot box, was the path to social transformation. The two renounced the electoral system and joined the city’s anarchist movement.

Advertisement

Anarchists in Chicago were almost entirely immigrants from Germany. Jones suggests that his experience working with Germans in Texas made Parsons comfortable with their Chicago counterparts. As a descendant of colonial Puritans and virtually the anarchists’ only English-speaking orator, Parsons was especially valuable to the movement—his presence proved that anarchism was not simply a foreign import.

Meanwhile, Lucy Parsons engaged in a program of self-education, attending weekly anarchist meetings and devouring radical books and newspapers. She soon established herself as a talented writer and lecturer. Her article “A Word to Tramps” in The Alarm, a periodical edited by her husband, became a widely reproduced “staple of anarchist propaganda.” In another piece, “Communistic Monopoly,” she joined numerous other radical writers of the era—Edward Bellamy being the most famous—who made their point by transporting a character to a future utopia. Unlike his authoritarian socialism, in her model of the good society small local associations, including trade unions and religious groups, governed the social order.

As American-born anarchists, Albert and Lucy Parsons were a minority within a minority. Their outlook, however, had more in common with that of their German associates than with other native-born anarchists, whose views represented an extreme version of common American values—suspicion of the state and celebration of unfettered individualism. European anarchists tended to be more collectivist in orientation. Their ideology, sometimes called anarcho-syndicalism, envisioned labor unions, not liberated individuals, taking over the functions of government. However, while many Chicago Germans denounced existing unions as hopelessly reformist, Lucy worked with the Chicago Working Women’s Union and Albert with the Knights of Labor and the Chicago Eight-Hour League.

One issue on which the couple fully agreed with other anarchists was their forthright advocacy of violence. They hailed dynamite, invented by Alfred Nobel in the 1860s, as the great equalizer in the class struggle. Dynamite would even the odds between a weak and fractured working class and the economic and political elite (which time and again proved quite willing to use violence to promote its own interests). Johann Most, the leading anarchist in Germany, preached the propaganda of the deed: acts of violence would awaken class consciousness and inspire a working-class uprising. He urged his followers to plant bombs not only in government buildings but, among other places, in ballrooms of the rich and churches.

Albert and Lucy Parsons, too, celebrated violence. Lucy urged tramps to “learn the use of explosives.” Albert advised members of one audience to “buy a Colt’s navy revolver, a Winchester rifle, and ten pounds of dynamite.” The Alarm published articles on how to make dynamite bombs. Despite their heated rhetoric, Albert and Lucy do not seem to have committed any acts of violence themselves. But others did. In Europe, Irish revolutionaries planted dynamite bombs in London and anarchists assassinated Tsar Alexander II of Russia and King Umberto I of Italy. In 1901 an anarchist assassinated President William McKinley. In 1910 the McNamara brothers, two radical unionists, bombed the Los Angeles Times building. An anarchist was probably responsible for the Wall Street bombing of 1920.

Today, after Timothy McVeigh, Osama bin Laden, and ISIS, loose talk celebrating violence seems rather less exhilarating than in the Parsonses’ era. Jones makes it clear that she believes their advocacy of violence was “largely harmless.” Few workers seem to have taken it seriously. A local newspaper, reporting on one of Chicago’s Sunday labor picnics, reported that after speakers harangued the crowd to arm themselves, listeners did—with beer. Jones points out that the Parsonses’ language was entirely counterproductive, needlessly frightening law-abiding citizens and allowing authorities to tar all radicals with the brush of insurrection.

To explain why the couple insisted on using such shocking language, Jones develops an elaborate scenario in which a symbiotic relationship developed between the Parsonses, the mainstream press, and the police. Albert and Lucy knew that advocacy of violence would attract attention the tiny anarchist movement could not otherwise enjoy. Reporters eagerly recounted their fiery speeches and interviews because such articles sold newspapers. Albert seems to have known the identity of undercover police agents who attended anarchist meetings. When they were present, he spoke even more vividly of violent class warfare so that their reports would rattle the city’s establishment. Meanwhile, police reports about his language justified the city’s pouring more and more public money into what would later be called its Red Squad. This interpretation seems too conspiratorial to be entirely persuasive. Another possibility is that the Parsonses believed in what they were saying and how they said it.

Advertisement

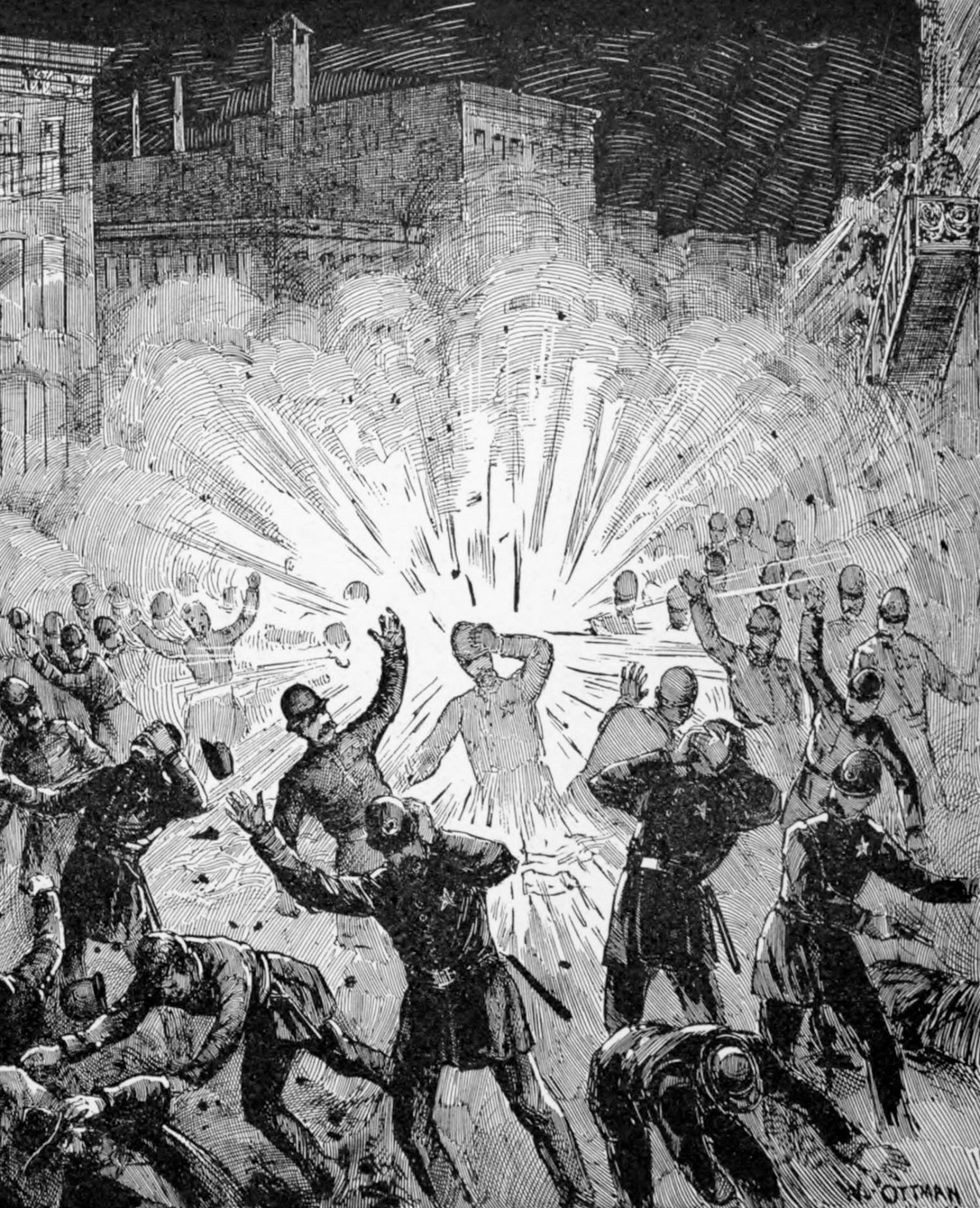

The turning point in Lucy’s life was her husband’s trial and execution. On May 4, 1886, a mass rally took place at Haymarket Square to protest the killing of four men when police opened fire during an altercation between strikers and strikebreakers at the giant McCormick agricultural machinery factory. Albert delivered one of the rally’s speeches, after which he and Lucy repaired to a local saloon. As the gathering was winding down, someone threw a dynamite bomb, killing a policeman. At least ten other people later succumbed to injuries, some from gunshot wounds, although it remains unclear if anarchists or police fired the shots.

Eight prominent anarchists (five immigrants from Germany, one from England, an American of German descent, and Albert Parsons) were put on trial for murder and conspiracy. The proceedings were notably unfair, beginning with the decision to try all eight together. Only two of the men had been present when the bomb was thrown, and Parsons had not even attended the meeting the evening before when the rally was planned. The judge openly displayed bias against the defendants and spent part of his time flirting with female admirers in the audience. The prosecutor told the jury to convict because anarchy itself was on trial. For his part, Parsons claimed, falsely, that he had brought his two young children to the rally, allegedly proving that he did not anticipate violence. All eight men were convicted. After fruitless appeals, four, including Parsons, were hanged. Having survived the Civil War and the violence of Reconstruction Texas, Parsons went to his death in Illinois for a crime he did not commit.

With her husband in jail (where he received a steady stream of visitors, some bringing food, cigars, and other gifts), Lucy Parsons came into her own. She embarked on speaking tours to raise money for the expensive appeals process. She spoke at union halls and saloons, and at highly respectable venues such as Cooper Institute in New York City. She insisted on her husband’s innocence but refused to renounce her views (she began her speeches by proclaiming, “I am an anarchist”).

In interviews Parsons repeated the tale that she had been born in Texas of Mexican and Native American ancestry. The mainstream press reviled her as “a sanguinary Amazon.” Reporters obsessed over the exotic appearance of this “dusky representative of anarchy,” dwelling in detail on her coloring, hair, and elegant clothing (she did not present the image of an unkempt rabble-rouser). But working-class audiences, whether they agreed with her anarchist views or not, saw her as a symbol of the judicial system’s class bias, and she succeeded in raising significant sums of money. Albert would long be remembered as a working-class martyr. John Brown, Joe Hill, Sacco and Vanzetti, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and Albert Parsons—execution elevated all of them to a fame that transcended their particular political views and the crimes they did or did not commit.

Lucy Parsons lived for over half a century after her husband’s execution. For years she pursued her career as an anarchist speaker and writer. She became a prominent figure in Chicago’s vibrant reform culture, in which groups of all kinds, from labor radicals to Christian socialists and settlement house workers, debated ways to ameliorate the dire conditions of the urban working class. As Jones relates, middle-class reformers proved remarkably willing to listen to a radical like Parsons. She even spoke before the ultra-respectable Friendship Liberal League and New Century Club. Parsons became a stalwart advocate of free speech, engaging in frequent battles with the Chicago police, who tried to prevent her from lecturing and displaying anarchist flags. In the early twentieth century she joined the free-speech fights of the Industrial Workers of the World. These battles remind us how much our civil liberties owe to radicals—abolitionists, anarchists, free lovers, labor agitators, black militants—all of whom had to fight for the right to disseminate their ideas without official persecution.

Despite her husband’s fate, Lucy Parsons did not retreat from the advocacy of violence. “Rivers of blood,” she said in one speech, would have to flow before social justice could be achieved. By the early twentieth century, however, she seemed a relic of an earlier era. Anarchism was changing as urban intellectuals and bohemians claimed the label for themselves. These new recruits did not idealize violence and were more interested in shattering social taboos, especially with regard to sex, than liberating the working class. Parsons did not find this stance appealing. Not that she was sexually conventional. A few months after Albert’s execution she began living with a younger man, and other lovers followed. But open advocacy of sexual freedom offended her. Women, she said, “love the names of father, home and children too well” to embrace the idea of free love. When Emma Goldman published her autobiography in 1931, Parsons, now eighty, criticized the “sex stuff” in the book and wondered why Goldman felt it necessary to identify fifteen of her lovers.

There is much to praise in Goddess of Anarchy, including Jones’s thorough research, which has laid to rest uncertainty about Parsons’s origins, and the ways the book illuminates the rapidly changing economic and political circumstances in which Parsons operated. A work that could easily have descended into a confusing litany of tiny organizations, short-lived publications, and endless speaking tours retains clarity and coherence throughout. Lucy Parsons finally receives her due as a pioneering radical. As Jones points out, Parsons was hardly the only flamboyant and enthralling woman orator of the industrial era—one thinks also of Goldman, the Populist Mary Ellen Lease, and the labor radicals Mother Jones and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. But she was the only woman of color; indeed it is probable that no nonwhite person of the era other than Frederick Douglass addressed as many Americans. Jones takes Lucy Parsons seriously as a speaker and writer, rather than reducing her to an adjunct of her husband.

Ultimately, however, the portrait is not sympathetic. As Jones makes clear, Parsons pursued her goals, personal and political, with “ruthlessness.” Jones chides both Albert and Lucy for thinking of the working class as an abstraction, ignoring deep divisions along lines of ethnicity, religion, race, and craft, as well as the fact that most workers valued their democratic rights and did not view the ballot box as a trap.

Candid criticism is always preferable to hagiography. Jones, however, sometimes seems to measure both Parsonses against an ahistorical ideal—the radical attuned to the intersections of race and class, the nuances of political strategy, and the impact of language, whose private life reflected his or her political principles. Not surprisingly, by this standard Lucy is found wanting. So would almost any human being. The great Debs enjoyed racist humor. Goldman preached free love but flew into rages of jealousy over the womanizing of her lover Ben Reitman. “Did she live life as an anarchist?” Jones asks of Parsons. The answer is no: Parsons failed to pursue the “playful” kind of life other anarchists aspired to, or to break openly with “stifling social conventions.” She was not, in other words, a New Leftist.

A scholar deeply committed to revealing the history of racial inequality, Jones frequently takes Albert and Lucy Parsons to task for their “pronounced indifference to the plight of African-American laborers,” in both the South and Chicago. Blacks were the most downtrodden sector of the working class, but the Parsonses said almost nothing about the particular exploitation—disfranchisement, segregation, lynching, etc.—to which they were subjected. American radicals, Jones writes, should be judged by “a single dominant standard”: the degree to which they participate in a struggle against racism. Lucy Parsons fails this test, politically and personally. Indeed, the book’s most serious charge is that she refused to embrace her identity as a black woman and former slave. Parsons, Jones believes, should have spoken for her race.

It is difficult today to appreciate that earlier generations may not always have been as preoccupied with race as we are. The Parsonses assumed that the liberation of the working class would benefit blacks as much as whites. In one article, Lucy wrote about the plight of southern blacks, but attributed it mainly to poverty, not racial oppression. This analysis is open to criticism, but it was one adopted by Debs and many other white radicals. At various points in our history, moreover, black activists and social critics have also challenged the primacy of race. As Jonathan Holloway shows in Confronting the Veil (2003), this was the position of Abram Harris Jr., E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche in important writings of the 1920s and 1930s.

The vexed question of the intersection of race and class has no single answer. But it seems misguided for Jones to conclude that Albert’s “indifference” to racial inequality in Chicago proves that his courageous efforts on behalf of blacks in Reconstruction Texas were “purely opportunistic,” or to criticize Lucy for going to great lengths to deny her “African heritage” (an intellectual and political concept less relevant in the late nineteenth century than today).

Political commitment is a choice, not an obligation. Throughout American history, some people of all backgrounds, like Lucy Parsons, have found it liberating to be part of an international movement with a universalist vision of social change, rather than seeing themselves primarily as members of a group apart. Then and now, DNA is not necessarily political destiny.

This Issue

December 21, 2017

Lies

Kick Against the Pricks

The Man from Red Vienna