In a museum of war, a fire breaks out—or just possibly is ignited by someone—and kills the museum’s creator. This is not surprising. He sleeps among his exhibits in a wooden coffin, wearing a samurai mask and a Prussian spiked helmet, and he smokes abundantly, flicking the butts out of the coffin as he grows drowsy.

Although he appears and reappears throughout Blameless, this figure is not exactly a protagonist. He is certainly heroic, a human bundle of generous actions and outbursts to which most episodes in this novel refer. Claudio Magris doesn’t give him a name. But in an author’s note at the end, he lets it be known that he had a real person in mind:

Professor Diego de Henriquez, a brilliant, uncompromising Triestine of vast culture and fierce passion, who dedicated his entire life (1909–1974) to collecting weapons and military materiel of all types to build an original, overflowing War Museum that might, by displaying those instruments of death, lead to peace.

Not because the weapons were ugly. On the contrary, de Henriquez wanted to show their awful beauty and superb technical ingenuity, alongside the astronomical sums of money that went into their construction rather than into making people healthier or wiser. He did indeed die in a fire, “in circumstances never wholly clarified,” after he had spent all his own money on acquisitions and faced impossible debts. But today, after a generation of neglect, the city of Trieste has taken over his scattered collection and housed part of it—death engines of the Great War, which began for Italy in 1915—in a spacious new museum on the Via Cumano.

The museum tries to be faithful to its founder, its “coltissimo e bizarro ricercatore.” This most cultured and bizarre researcher must have been impossible to work with, but he was also impossible to resist. Blameless tells anecdotes about him so extravagant that I was sure Magris had made them up, but on a visit to the museum in Trieste I found that almost all of them were true. De Henriquez did beg weaponry from armies on the battlefield, even before World War II was over. He cajoled them from the Germans, from Italian arms factories, from the Yugoslav partisan armies that briefly occupied Trieste in 1945, from the Allied military government that succeeded them, from local councils anxious to be rid of the smoking scrap metal blocking their streets. It’s not fiction but historical truth that, on his own, de Henriquez negotiated the final surrender of Trieste’s German garrison to a New Zealand tank brigade. And General Hermann Linkenbach, the German commander, really did give him his own braided and beribboned tunic in gratitude (de Henriquez used to wear it on proud occasions). It’s also true that the Germans allowed him to choose an example of each of their weapons before they handed them over to the New Zealanders.

This is a war museum like no other. The black iron hulks of siege guns are Futurist-sculptural; the intricacies of a rangefinder or the feed system of early machine guns are shown as masterpieces of human ingenuity. Beside them are diagrams of mortality and money. The Triple Entente and its allies called 48.1 million men to arms in World War I and lost 5.6 million dead (the British share of that achievement alone cost $49 billion).

Beyond the weaponry, to one side, are the results of all that beauty and inventiveness and investment: photographs of the torn, headless, helpless bodies of young men. The thoughts of Diego de Henriquez are on the walls. Some, like “War=Death, Peace=Life,” once the slogan over the entrance, are straightforward enough. Others, concerning his “International Center for the Abolition of Wars and for Universal Brotherhood,” are more challenging. If there were such a thing as a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize, de Henriquez should obviously win one. But then it’s not quite clear that he believed in being posthumous, because he did not quite believe in death. He called his museum “the first center in the world for the reading and modification of the past, and of the future through the inversion of time as a consequence of loosening space-time in order to abolish evil and death.”

What might this mean? The Trieste authorities have stuck the proclamation up on the museum wall but don’t presume to decrypt it. They are spending much time and money and imagination on behalf of this man; they describe him, beautifully, as “the prisoner of a dream we now wish to make our own.” But for Magris those words begin to glow with significance. A novelist knows all about loosening space-time and inverting the flow of time to run backward. Magris makes his de Henriquez character declare that “death does not exist…it is merely an inverter, a machine that simply reverses life like a glove, but all you have to do is let time flow backward and everything is reclaimed.” The “fire-breathing objects in the Museum” will become

Advertisement

nightmares of a troubled, dispelled dream, a film projected backward, beginning with death and destruction and ending with people…ultimately happy and smiling, to make it clear that death, every death, comes before life, not after.

At first, it seems curious that Magris does not give a name to this figure who is and isn’t Diego de Henriquez. But with this author the namelessness is not accidental. Magris doesn’t do character, or not in the conventional way. Many other people in Blameless have names, and yet the reader is allowed little sense of what they are like beyond the odd mention that they have beautiful hands or are putting on weight. There are detailed accounts of what they do and—in long, elaborate flights of discussion and imagery—of what their experiences do to them. We learn a lot about them, but there’s no attempt to set up what most fiction sets up: the illusion of recognizing a real person. Perhaps Magris has in mind Muriel Spark’s darkly theological warning that the novelist commits the worst of mortal sins against God by creating human beings without the capacity to redeem themselves.

Blameless revolves around the city of Trieste, the town of Italo Svevo and James Joyce to which Magris also belongs. Trieste is a small but ancient Adriatic city, liminal between several worlds. It was once the main port and naval base of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; today, it perches on a spit of Italian territory fenced in between the Slovenian frontier and the sea. From its Habsburg, Slav, and Italian background grew a diverse population with a gift for backing swaggering losers and then for adjusting loyalty to the next conqueror. The main action of the novel takes place between the Fascist 1930s and the city’s liberation in 1945, concentrating on the years of German-inflicted terror at the end of the war. After Italy’s surrender in 1943, the northern shores of the Adriatic, including Trieste, were directly annexed to the Reich and occupied by the Wehrmacht and the SS, which established the only Nazi concentration camp on Italian soil.

The Risiera in Trieste was an old brick rice mill, today a museum. There—while most Italians looked the other way—German and Ukrainian guards murdered some three to five thousand people by gas chamber, firing squad, and wooden bludgeon. Their victims were members of the Italian resistance, civilian hostages, Slovene nationalists and partisans, and patients from mental hospitals. (That is not counting the Jews of Trieste and the Veneto. The Risiera men killed only a few dozen of them, herding the rest into trains bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau.) Human ash and bone from the crematorium ovens were dumped in an inlet of the Adriatic, where they still coat the sea floor.

In that period, many important people in Trieste behaved in ways they later preferred to forget. Postwar officialdom saw their point. The Italian title of this novel is Non luogo a procedere (No Grounds for Further Proceedings): this was the welcome conclusion of the magistrate appointed to investigate allegations of collaboration with mass murder at the Risiera. The recent past had not only to be forgotten. It was necessary to forget that you had even forgotten. As Magris puts it, “not…oblivion, but…oblivion of oblivion.”

In the novel, that is exactly what the museum founder tries to reverse at the end of his life. As the real de Henriquez did, he goes to the Risiera as soon as the slaughterers have left and finds the walls covered with thousands of scratched and scribbled graffiti, the last messages of those who knew they were about to die and—often enough—the names of those individuals in Trieste who denounced them to the Gestapo. He copies all the inscriptions down in notebooks, partly as an “inverter” to bring the dead back to life and partly because he anticipates what did in reality happen.

Someone in the Trieste police, whose leaders had collaborated comfortably with the Nazis, had the walls rapidly and thickly whitewashed. The oblivion of oblivion. But the notebooks remained. In the novel, they disappear after the curator’s death in further “circumstances never wholly clarified.” In the Via Cumano museum, though, all de Henriquez’s notebooks are preserved: 287 volumes, containing 38,000 pages of close, neat writing and drawings. (Some of the prisoners drew faces of women and portraits of their SS guards on those walls, and he copied them as well as the graffiti.)

It’s an attractive trait in Magris that he so obviously can’t resist a good story. He seems to collect them from all over the world, sometimes from neglected archives or forgotten books, sometimes from contemporary media or chance conversations. The peculiar structure of Blameless reflects this: a string on which powerful stories hang loosely threaded like beads. The string is the tale of the museum founder, his visions and passions, and his end. But the beads?

Advertisement

After twice reading Blameless, it was still not easy to see how these stories—in themselves often marvelously vivid and ironic—relate in any direct way to the narrative of the war museum and its obsessed director. True, they deal very broadly with some of his themes: deceit and cover-ups, the ghastly ambiguities of war and of those chosen to be its heroes, the sense of exile that never leaves those who have been persecuted because of their race, the loneliness of difficult individuals driven by the need to find and publish the truth. But the reader may come to feel—and I think that it should be a warmly sympathetic feeling—that Magris was bursting with stories simply too good not to tell and dropped them into the mix, trusting, as writers do, that they would somehow work their way into being (those boring words) “appropriate” or “relevant.”

Luisa’s story is not like the others, in that it recurs in installments throughout the novel, in a sort of counterpoint to the tale of the tragic collector himself. She is introduced at the beginning as an administrator, appointed by the city to plan the new museum and bring together all the weapons and vehicles and papers that have lain scattered in hangars and sheds and backyards during the decades since the collector’s death. But her own life, her own past, turns out to be a journey across familiar Magris themes: the cover-up of evil and the transit between identities.

Luisa is the daughter of two racial outsiders who had a brief, loving marriage. Her father was a black American soldier from a Creole-Caribbean background who was posted to Trieste. Her mother, Sara, was a Triestine Jew, saved as a child because her own mother, Deborah, hid her with a Slovene family on the Istrian coast. Returning after the war, Sara finds that her beloved mother had been seized on the street and sent to her death, along with most of the other Jewish families and those who tried to save them.

But as Sara grows up, she realizes that there is embarrassed evasion around her mother’s fate. Something terrible is being covered up. There are sudden silences, awkward changes of subject, and then, finally, a screaming outburst from a survivor. How was it that, a few days after Deborah’s arrest, the Germans raided the house where she had been hiding and took away to their deaths all the other Jews there and the Italian lawyer who had been sheltering them?

Nothing is certain. But Sara’s life enters a long darkness: “How she envied that gift that seemed given to others, to so many others, to almost everybody; the ability to forget, or at least to live as though you had forgotten.” The darkness is lifted by her happy marriage to the American soldier—two people whose races leave them with an inescapable sense of exile—but falls again when he is killed in an airfield accident. Luisa, their daughter, is doubly bereaved. Their very happiness excluded her, and as a young woman she knows that she will never find her own way into such certainty of love.

The courtship and contentment of Luisa’s father and mother are beautifully told by Magris. They are both, as he puts it, singing “the songs of Zion in a strange land,” and yet they do not allow grim events—his sister is set upon in a London pub because of her skin color and kicked to death—to dismay them. He explains to his small daughter that she is named after another Luisa. This is the legendary Luisa de Navarrete, a freed slave who was abducted from Puerto Rico in the 1580s by Carib raiders from Dominica.

Here begins another elaborate Magris “true story,” all about ambiguous identity and cover-up. Over years of exile, this Luisa assimilates with her captors and adopts the ways of the Kalinago tribe, becoming the passionate mistress of their chief. But on her return, she is arraigned and threatened with death as a pagan witch; to survive, she invents a narrative of ceaseless torment by her kidnappers and rape by their chief, and pleads—dishonestly but successfully—that all she has ever wanted is to be a Christian “good wife.” Now her namesake, in her museum office, is wondering where to display a Chamacoco war club from Paraguay.

This diverts the novel off into the long, tangled story of Alberto Vojtěk Frič, the historical Czech botanist and ethnologist who assembled the world’s first serious collection of cacti and gave his heart to the Chamacoco people in the Paraguay rainforest. Frič brought one of them, the princely Cherwuish, to Prague, where he became a fashionable sensation—this was in 1908—and was whirled from writers’ cafés to avant-garde theaters without really understanding the voyeurism of his audiences. Jaroslav Hašek met the original Cherwuish, now nicknamed “Červiček,” and found his Prague adventures entertaining enough to write a story about him.

But in Magris’s version, at least, Červiček’s bewilderment began to turn violent and he ran increasingly wild, fighting the Habsburg gendarmerie in the street and leaping onstage at a Yiddish theater performance that he mistook for a tribal dance party. Frič eventually took him home to South America. In the novel, Cherwuish vanishes in the carnage of the Chaco War, the meaningless struggle between Bolivia and Paraguay that Magris describes in pages of horrible eloquence, war’s madness as seen through the doomed Cherwuish’s imagination. (Historically, Cherwuish took no part in that war, but lived on for many years as an elder respected for his strange experiences.)

Frič reappears later in Blameless. But now it is the 1940s, and he is a sick old man dying among his rotting cactus collection in Prague during the Nazi occupation. This allows Magris to recount at length the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the merciless Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, and the tragedies that followed. First, the heroic death of his killers, cornered in a Prague church crypt, and then—following Hitler’s order to “shoot ten thousand Czechs” in retribution for Heydrich’s death—the extermination of the village of Lidice and its inhabitants. The only act of resistance by Frič has been to put some cacti behind the benches in the Waldstejn Gardens, “so that German soldiers, when they go there with Czech girls, might maybe get pricked in the ass.” He expires fancying that he is changing into one of his own cacti, which in turn resembles Hitler’s face: “prickly spines, the Führer’s mustache—I can make him die, the cancer is spreading and has completely invaded me, I am him and I’ll let myself die, and him with me.”

Another ambiguous death that is either heroic or heroically unheroic, depending on which you want to believe, is that of Private Otto Schimek, a young Austrian conscript in World War II. The excuse that Magris finds for retelling this rather well-known mystery is the sight of a German MP-44 machine pistol hanging on the museum wall. This represents either the gun that young Schimek laid down when he refused to join a firing squad to shoot Polish hostages or the gun that he threw away when he decided to become a deserter. Whichever he did, he was shot for it in November 1944 by Feldgendarmerie military police, near the village of Machowa in Nazi-occupied Poland.

That much is agreed. So is the fact that Schimek thought the war was wrong and un-Christian. Nothing else is certain. Magris skillfully ventriloquizes the voices of journalists, historians, priests, and politicians in the miserable controversy that broke out later. Church and state in Poland, supported by Pope John Paul II and the Austrian chancellor, set about recruiting him as a noble martyr for peace and Poland and a candidate for sainthood.

Pilgrimages to his grave began (it has since been found to contain someone quite different), and soon there was a first miracle of healing. But meanwhile, the two journalists who had first broken the Schimek story, an Austrian and a German, did more research and developed doubts. There was no evidence that Schimek had refused to shoot anyone. But there was evidence that he had deserted and had been caught by the Feldgendarmerie in a Polish street, dressed in civilian clothes with a loaf of bread under his arm.

A mudslide of hate fell on the researchers who had changed the story. They were sullying a hero of faith, truth, and love; they were cynical intellectuals, probably Communists, almost certainly Jews. But in the Trieste museum, Luisa still wonders which version is true. Perhaps, she reflects, truth is a sort of landmine that

begins by destroying others and ends up destroying itself; it knocks the pedestal out from under an idol, and crash-bang! the idol falls, but then it smashes the plinth on which the pedestal rested…until the ground all around caves in and even the truth is sent flying.

And Magris makes one of the researchers say that

instead of photographs and begonias, they should just place a nice big loaf of bread on that grave in Machowa…. He deserves it, the glory, because of that loaf…. Real, tangible, something you can chew and put in your mouth or maybe even give a piece to another starving man, never mind plaques and songs and medals, bread is bread.

It was inevitable that Magris—a pied piper of fiction—would lead his mesmerized readers a few miles out of Trieste to the white walls of Miramare. The little palace leaning over the sea was built in 1856 by Archduke Maximilian, brother of the Austrian emperor, for his young bride Charlotte, daughter of the king of the Belgians. But it is Maximilian’s pathetic decision to become emperor of Mexico, only to die before a firing squad at Querétaro, that Magris wants to imagine. That, and Maximilian’s discovery of a new species of bedbug, which opens into a witty, leisurely Magrisian disquisition on bedbugs and their remarkable agility. Mention of the castle then evokes another “memory”: a drunken orgy in April 1945 as the Nazi and Fascist rulers of Trieste, knowing that defeat and retribution are only days away, celebrate Hitler’s last birthday at Miramare.

There are many other anecdotes rattling or jingling on this long, heavy necklace of a book. Sometimes Claudio Magris’s prose can seem self-indulgent, overweight with its endless aphorisms and recondite allusions. But in the end Blameless, wonderfully translated by Anne Milano Appel, succeeds as a prayer for mercy and reason in a world of torturers and whitewashers. And Magris can, when he wants, write with the economy of a master artist. Here is Luisa’s mother, locked into her own despair:

Life is out there, what you catch sight of when the windshield wiper momentarily clears the glass obscured by rain or snow.

If you can wait for epiphanies in this novel, you will find them.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

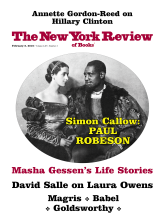

The Emperor Robeson