The Anglican choral tradition is one of the great successes of English cultural diffusion, to rank with Association Football (soccer), cricket, and the works of William Shakespeare. It has a cultural heft way beyond its parochial and very specific origins, and it turns up in the oddest places. The most incongruous example must surely be the upmarket gloss that Thomas Tallis’s forty-part motet Spem in Alium lends to a down-and-dirty scene in the film Fifty Shades of Grey.

I’m often surprised by how far this music travels. The transposition of the Anglican sound world into the urban jungle of New York seemed rather miraculous the first time I walked into Saint Thomas Episcopal Church on Fifth Avenue to bathe in the glories of stained glass–inflected light and English-inflected harmonies. On another occasion, I was in Jacksonville Beach, Florida, for a concert, arriving just after a school shooting in next-door Jacksonville that had made me preternaturally alert to the cultural differences between the Old and the New Worlds. But it turned out that the concert was in St. Paul’s by-the-Sea Episcopal Church. Our greenroom was the church vestry, and I felt strangely at home among the cassocks and surplices, The Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems (some nice Tallis there), and the familiar hardcovers of Hymns Ancient and Modern and The English Hymnal, the red and the green.

I grew up on the fringes of this Anglican culture, and I remain at one and the same time drawn to it and stoutly resistant. Resistant because in the mainstream classical world of opera and song in which I work, a church sound is often frowned upon whenever a hint of it (the withdrawal of vibrato from the voice, for example) is detected or imagined. Drawn, because from the ages of seven to twelve or thirteen I sang, una voce bianca as the Italians call it, in the humble precincts of St. Leonard’s, a parish church in Streatham, South London. Its glory days had been in the eighteenth century, the days of the so-called Streatham worthies, when the likes of Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, Edmund Burke, and Oliver Goldsmith—all friends of the wealthy brewer Henry Thrale—hung out in what was then a mere village. Samuel Johnson was a regular worshiper.

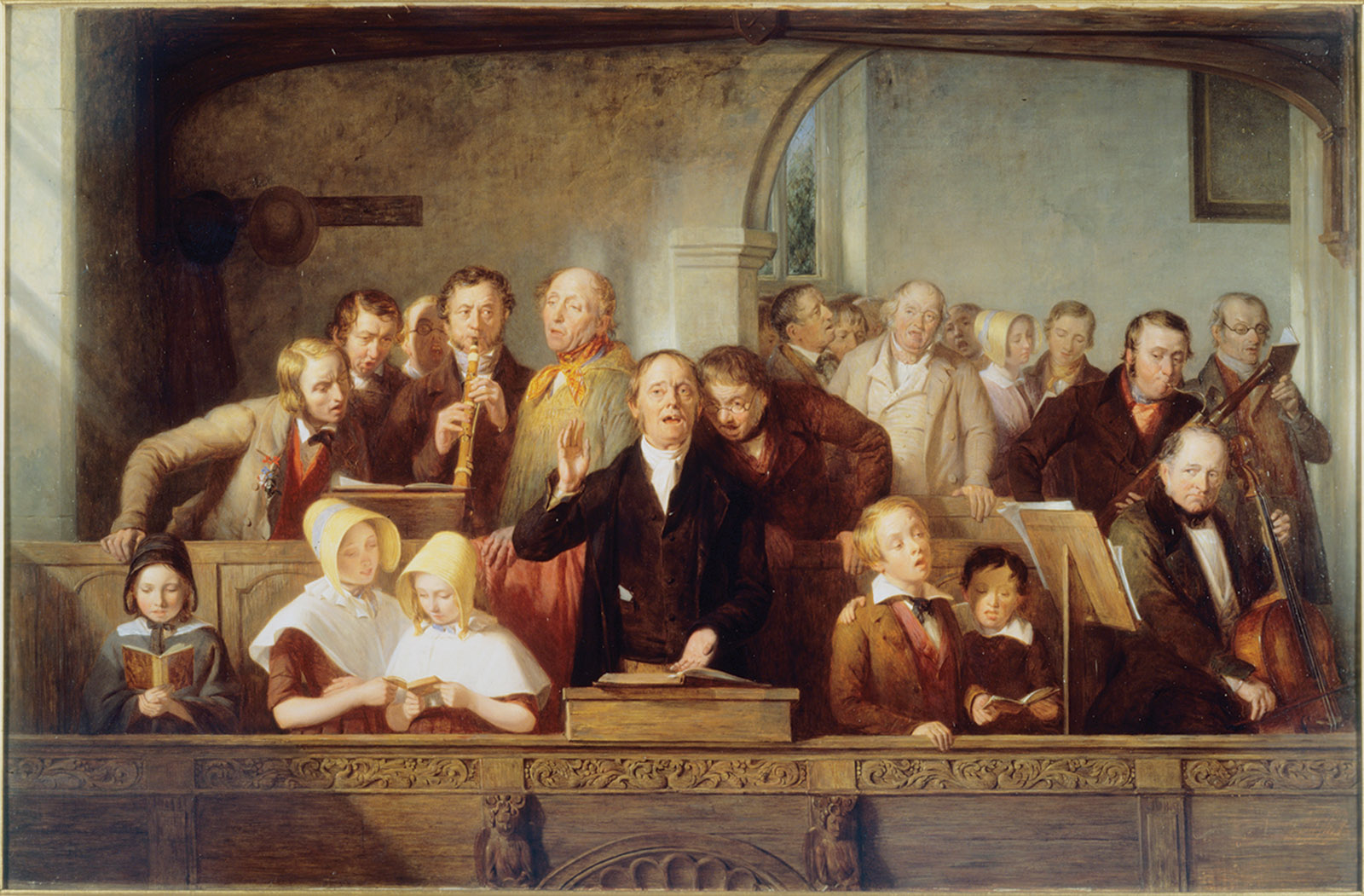

By the 1970s St. Leonard’s was part of the anonymous London sprawl, on the way down, and yet the church choir, under the leadership of an inspiring organist and choirmaster, Tom McLelland-Young, kept alive the flame of a musical tradition that—as Andrew Gant, in his history of English church music, O Sing unto the Lord, makes clear—can trace its roots back to late antiquity. With limited resources we performed the Passions of Johann Sebastian Bach (in truncated form) and anthems by Counter-Reformation masters such as the Italian Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and the Spaniard Tomás Luis de Victoria. But at the core of our repertoire (though I hesitate to use that rather professional word) was the glorious inheritance from the English Reformation and its immediate aftermath—Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, the exotically named Orlando Gibbons, John Blow, Henry Purcell—and the music that was created in an attempt to recreate that beauty of holiness: the Victorian and Edwardian anthem tradition of Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford, Herbert Howells, and many others.

Gant’s book is particularly fascinating for a former suburban choirboy like myself because it explains a lot of things that at the time seemed either rather mysterious or just to be taken for granted. Psalms, for example—sung by choir and congregation—seemed to occupy an inordinate amount of the morning service, and the junior members of the choir spent much of the sermon sniggering over the psalmist’s more recondite imagery, usually in psalms we never sang but found in the prayer book, and which we somehow conjured into a vague impropriety (“my mouth is dried up like a potsherd and my tongue cleaveth to the roof of my mouth” seemed unaccountably hilarious).

Psalm-singing was, as Gant makes clear, one of the major strands of post-Reformation church music in England. It was a vital part of congregational singing from the 1500s on, a totem of Protestant rectitude, and a site of struggle between populist instincts and clerical control. It had migrated from the evangelical movements of continental Europe and fit well into a political culture that celebrated English reform as a resurrection of the blessed biblical Israel: in 1560, Bishop John Jewel celebrated mass psalm-singing at Paul’s Cross in London and wrote that “you may now sometimes see…after the service, six thousand persons, old and young, of both sexes, all singing together and praising God”; Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army went into battle with psalms on their lips. But the songs that congregations loved to sing in church and that the clergy sought to control were metrical psalms (they stood, strictly speaking, outside the approved liturgy); they were rendered into rhyming English verse and sung as what we would nowadays call hymns. Gant gives the example of Psalm 84, “How pleasant is thy dwelling place,” married in Thomas Ravenscroft’s 1621 Psalter to a tune that in our own day is better known as “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks By Night” (which naughty choirboys inevitably garbled into “while shepherds washed their socks by night”).

Advertisement

The psalms we sang back in the 1970s, and which continue to be sung in Anglican or Episcopalian churches and cathedrals today, are something rather different from this metrical populism. Anglican or English chant—which dates back to the sixteenth century but didn’t triumph until the nineteenth—was a matter of matching the natural speech-rhythms of the psalm to the notes of a simple harmonized melody. It thus preserved the authorized translation of the psalm in question and created an echo of monastic chanting, although the tunes were far removed from the Gregorian austerity of medieval times. I seem to remember our leading the congregation in the singing of these psalms, but it’s a tricky business (it involves singing a lot of words to the same note, and changing at just the right moment) and nowadays left mostly to the choir alone.

The other crucial elements of English church music, and its twin glories, are hymn-singing and the anthem, which stand at the alternate poles of populism and elitism in religious practice. Hymns have been a feature of Christian worship almost from the very beginning, of course, as songs of praise and adoration of the Divinity. Lutheranism is deeply rooted in congregational hymn-singing; its most famous hymn, “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) is a sturdy embodiment in music and words of a movement built on Luther’s declaration Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders (Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise). Bach’s Passions are structured around the congregational singing of Lutheran hymns. Calvinism, the other main current of early Protestantism, was queasier about anything that was not the licensed word of God appearing in a church service (hence the nervousness about metrical psalms).

The Church of England, carried this way and that in rival versions of the evangelical current (not for nothing did the Venetian ambassador to the court of Elizabeth I say that as far as religion was concerned, England was a country “where men change their beliefs from day to day”), ended up pursuing a sort of middle way. This, the typical Anglican “fudge,” as Gant calls it, happened less by design than as a series of historical accidents. The Calvinist tendencies of the English establishment kept the singing of hymns in church at bay until relatively late: “I do not reconcile to the consistency and propriety of our Church duty the unauthorized introduction of the Morning and Evening hymn,” wrote William Charles Dyer in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1814.

Yet in the well-populated margins—among dissenters and Methodists—the eighteenth century had seen the birth of a hymn-writing tradition. Its most prolific figures were the dissenter Isaac Watts (1674–1748), credited with the authorship of around 750 hymns, and Charles Wesley (1707–1788), founder with his brother John of the Methodist movement, who wrote an extraordinary six thousand hymns plus another three thousand devotional poems. When the Oxford Movement of the nineteenth century discovered a definitive place for hymn-singing within the Anglican church service itself, there was a broad repertoire to draw on, from across the confessional spectrum, theologically diverse as to text, and promiscuous as to music (harmonized folk songs, composed tunes from oratorios, and Moravian melodies had all found their way into the melting pot). Hymns Ancient and Modern was first published in 1861, The English Hymnal in 1906.

Hymns have migrated out of the church building into public ceremonial (“O God, Our Help in Ages Past” at remembrance services for the world wars), schools (“I Vow to Thee, My Country”), and the sports field (“Abide with Me” or “Cwm Rhondda” at soccer matches). As with so much of the cultural inheritance we feed on and at the same time demean, most of the hymns sung in Anglican or Episcopal churches are overwhelmingly either Victorian or composed as part of the Victorian religious revival. The weight of condescension has been heavy—Gant notices the number of times music scholars or historians have called the Victorian hymn tradition “debased”—but these songs of praise do not merely project “a cast-iron certainty of being right with a certain sentimentality of expression.” They are also capable of expressing tenderness, meditation, doubt, and yearning. The melodic undertow of a quintessentially Victorian anxiety courses through them, sometimes at one with the words, sometimes cutting subtly against them, and creating a dynamic irony that reaches well beyond the stereotypical complacency.

Advertisement

Some of the most famous hymns have complicated genealogies, like the aforementioned “I Vow to Thee, My Country.” It originated before World War I as a poem but was only transformed into a hymn in the 1920s, requisitioning the great central tune from Gustav Holst’s “Jupiter” in The Planets. Its words express gentleness, peace, and the tragedy of sacrifice rather than the unthinking patriotism they are so often supposed to embody.

Hubert Parry’s “Jerusalem” is perhaps the most complicated of all, and the most representative of the multitudinous and curious sources of English hymnody. The text is by William Blake and forms the preface to his Milton: a Poem. Its “dark Satanic mills” and call for a New Jerusalem in “England’s green and pleasant land” are hardly the stuff of orthodoxy. Indeed, Parry wrote his setting not as a hymn but as a political song, intended for a “Fight for the Right” campaign meeting at the Queen’s Hall in London in 1916. In the depths of war despondency, the poet laureate, Robert Bridges, rather counterintuitively thought that a song made from Blake’s radical verses, anti-establishment to their core, forged in the heat of coruscating irony, might “brace the spirit of the nation [to] accept with cheerfulness all the sacrifices necessary.”

Having written the song, which begins “And did those feet in ancient Time,” Parry, who was something of a radical, developed misgivings that almost led to his withdrawing it; only adoption by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies saved it. Despite all this, and its technical failure to qualify as a hymn at all (it includes not one word of praise of the Godhead), “Jerusalem” has gone on to conquer the world, sung at the state funeral of Ronald Reagan in Washington National Cathedral in 2004 and at the royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton in Westminster Abbey in 2011.

Reading O Sing unto the Lord set me thinking about the hymns I love—these tunes that according to Gant “did for the English what opera did for the Italians.” What gives them, beyond nostalgia, their particular power? “My Song Is Love Unknown” is a text by the mid-seventeenth-century Church of England minister Samuel Crossman, from his “Young Man’s Meditation” of 1664, which has as one of its epigraphs George Herbert’s contention “A Verse may find him whom a Sermon flies, And turn delight into a Sacrifice”:

My song is love unknown,

My Saviour’s love to me;

Love to the loveless shown,

That they might lovely be.

O who am I,

That for my sake

My Lord should take

Frail flesh, and die?…

Here might I stay and sing,

No story so divine;

Never was love, dear King,

Never was grief like thine.

This is my Friend,

In whose sweet praise

I all my days

Could gladly spend.

On the page these verses are by turns meditative, introspective, and outraged. They reflect Crossman’s personal saving faith and the institutional faith of the church to which he belonged, but they were actually composed at what must have been a time of anxious moral questioning for the poet. Ejected from the established church in the wake of the Restoration settlement that followed the Civil War and Interregnum of 1642–1660, he wrestled with his conscience, took the necessary oaths, and was ordained afresh in 1665. His own sense of isolation surely lent his identification with Christ’s loneliness and his need for Christ’s saving love an added intensity.

More than two and a half centuries later, in 1925, the composer John Ireland set Crossman’s poem to music, in a masterpiece of protean strophic setting—the tune as harmonized seems to open a myriad of emotional possibilities that allow it to track the text with an unerring sensitivity. At its heart, though, is a melody of ineffable tenderness, a tenderness that is sometimes concealed in lusty congregational renderings with organ. Ireland claimed to have written the setting in a bare fifteen minutes, but the casual virtuosity that this implies belies the deep personal source of the introspective lyricism that makes this such a masterpiece. What after all was the resonance of this “love unknown” for a homosexual like Ireland, living the life of the repressed?

To turn to the other pillar of Anglican music, there is a paradox at the heart of the anthem tradition. English church music was renowned in the late Middle Ages. In 1440, a French poet, Martin le Franc, praised the Burgundian school for having taken on board the English way of writing music:

They have found a new practice, a way of making sweet consonance, in music high and low, in different shades, and rests and pauses, and have taken on the English manner.

The renowned Flemish theorist and composer Johannes Tinctoris, writing a little later, was clear about the origins of the European musical renaissance:

In this age the capabilities of our music increased so miraculously that it would seem to be a new art. Of this new art, as I might in fact call it, the English…are held to be the source and origin.

Yet while the fifteenth century was in many ways a glorious age for English music and saw individual composers, no longer anonymous, moving for the first time into the limelight, it was the trauma of the English Reformation from the 1530s on that somehow resulted in an outpouring of immortal music that still speaks to us today. The Reformation was, as Gant pithily puts it, siding with a particular revisionist strand of recent historiography, “an insurrection by the government against its own people…with the added complication that the government kept changing sides.” It produced the dissolution of the monasteries, with the attendant destruction of much of the musical fabric of the country, a revolution in but also a prolonged uncertainty about the status of the liturgy, and a devastating loss of existing books and manuscripts comparable in its effects on musical life to that of the iconoclasm of the 1530s and 1540s upon the visual arts.

Crisis inspired art. If the Elizabethan age was the age of Shakespeare, it was also that of Thomas Tallis and William Byrd. The politico-theological ferment that so obviously fed the playwright’s imagination may have, less directly, lent a certain expressive tension to the masses and motets of these two great composers, both royal servants who remained orthodox Catholics in a period of Protestant ascendancy that, for some, amounted to a Protestant terror.

In 1581 the Jesuit missionary Edmund Campion was hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason; a fellow Jesuit, Henry Walpole, wrote a poem in protest, “Why do I Use my Paper, Ink and Pen?” Byrd set it to music. The Recusancy Act of 1593 imposed fines and eventual house arrest on those who failed to attend Anglican worship; between 1592 and 1595 Byrd nonetheless wrote and published his three great settings of the Latin Mass, a service officially outlawed under the new dispensation. Yet Byrd was also, in the midst of all this, a loyal servant of the state: in 1588, after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth had written a poem extolling her triumph, “Look and bow down thine ear, O Lord, from thy bright sphere behold and see thy handmaid and thy handiwork.” Byrd set it to music as part of the victory celebrations.

We cannot be sure exactly how Byrd managed to reconcile the demands of private conscience and public service, or how his employers at court regarded his ambiguous engagement with treachery. His Quomodo cantabimus, a psalm text about the Babylonian captivity, speaks to a sense of internal exile; and toward the end of his life Byrd increasingly withdrew into crypto-Catholic circles away from court. The glory days of this first great flowering ran from the Reformation to the Glorious Revolution in 1689, when the Protestant settlement finally triumphed under the aegis of a foreign prince, William of Orange, culminating in that titanic figure Henry Purcell—a tumultuous era in which the outcome of ecclesiastical politics remained distinctly uncertain. But it is worth remembering that most of the great composers of church music of the twentieth century were also familiar with a sense of cognitive dissonance that faintly mirrored that of William Byrd.

Benjamin Britten, for example, was no true believer, at best an agnostic and a humanist admirer of Christian ethics; yet he produced some of the greatest church music since Purcell. His most monumental work of religious music, the War Requiem, is riddled with unorthodoxy and skepticism. Written for the reconsecration of Coventry Cathedral in 1962, it combines a brilliant reenactment of the Continental tradition (Mozart, Verdi, Fauré) in its rendering of the Latin Mass for the dead with highly personal settings of the poems of Wilfred Owen. The effect is highly ambiguous, as quasi-liturgical music rooted in gestures inherited from the past is confronted with Owen’s angry sense that organized Christianity has betrayed the pacifist ethic of its prophet. The Agnus Dei, sung by the choir, is cruelly juxtaposed with lines such as these from the tenor soloist:

Near Golgotha strolls many a priest,

And in their faces there is pride

That they were flesh-marked by the Beast

By whom the gentle Christ’s denied.

The most iconic work of the English choral tradition, and the most famous, with its rousing “Hallelujah” chorus, is surely Handel’s Messiah (1741), the subject of Jonathan Keates’s new and excellent brief study. Keates, a distinguished biographer of Handel, sets out to examine the origin and afterlife of the piece, and to establish what an eighteenth-century critic might have called its “sublimity.” Keates celebrates its “emotional range, the ways in which it embraces the multiplicity of existence, the directness of its engagement with our longing, our fears, our sorrows, our ecstasy and exaltation, giv[ing] the whole achievement an incomparable universality.” Keates recognizes that Handel was as spiritual a composer as J.S. Bach, his Messiah as rooted in that spirituality as Bach’s Passions were in his; Keates will have no truck with the tradition that “pigeonhole[s] Handel as a cynical opportunist, a shrewd entertainer with an eye on the market.”

I say “the English choral tradition,” yet Messiah was not written for a church, and George Frideric Handel (born Georg Friedrich Händel) was only an Englishman by adoption. Arriving in 1710 after early musical service in Halle, Hamburg, Hanover, and Italy, he established himself at the English court and in London society and became a cultural embodiment of the Hanoverian regime that had guaranteed the security of the Protestant establishment after the death of Queen Anne in 1714. The decades before Messiah were devoted to reams of masterly Italian opera (Ariodante, Xerxes, Alcina, and so on); to royal church music, most famously for the coronation of George II (“Zadok the Priest” is still sung at British coronations to this day); and, increasingly, to the new form that he invented, and to which the years after Messiah were devoted: the English oratorio, Bible stories dramatized but not fully staged (Samson, Saul, Jephtha…). The music of Messiah draws on all these strands, sometimes reworking music with a decidedly Italian secular origin to religious purpose and adding a good dose of Purcell-inflected Anglicanism.

Messiah was first performed at the music room in Fishamble Street in Dublin, immediately after Handel’s withdrawal, sick and exhausted, from the Italian opera scene in London, which had been such a central part of his life. Originally a concert piece, it is decidedly theatrical in character, something reflected in the series of effective stagings of the piece that have been mounted by opera houses in recent years. Its first roster of soloists included the actress Susannah Cibber singing contralto (“Behold, a virgin shall conceive”; “He was despised and rejected of men”). “Her voice was a thread,” wrote Charles Burney, the eighteenth-century music chronicler, “and her knowledge of Music very inconsiderable, yet by a natural pathos, and a perfect conception of the words, she often penetrated the heart, when others, with infinitely greater voice and skill, could only reach the ear.” Cibber was a scandalous figure in London society, and it was said that Dr. Patrick Delany, the chancellor of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, on hearing her sing “He was despised,” was moved to exclaim: “Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven thee!”

Handel was without doubt moved by a deep religious instinct in creating Messiah. Of composing the “Hallelujah” chorus, he spoke in visionary terms: “I did think I did see all heaven before me, and the great God himself.” Praised for the “noble entertainment” that was Messiah, he was a little uncomfortable: “I should be sorry if I only entertained them. I wish to make them better.” Yet there is a sort of insoluble cognitive dissonance at the core of Messiah, a mysterious ideological fault line, as there is in so much English choral music, from William Byrd to Benjamin Britten.

Messiah is called an oratorio, but it is very different from Handel’s other works in that genre. It tells a story, but it is the story of Christ, not of an Old Testament hero. Its text is mainly assembled from Old Testament prophetic writings about the coming of the Messiah, and despite the drama the music brings, the compilation serves a very particular ideological purpose in emphasizing what Saint Paul called the “Mystery of Godliness” and the reality of the Incarnation. It is, at least in part, an anti-deistical tract.

The compiler, Charles Jennens, was a nonjuror, one of that small number of Protestant Englishmen who remained loyal to the House of Stuart (expelled for their Catholicism) and regarded the Hanoverian kings, despite their reformed faith, as usurpers. Nonjurors were unwilling to swear oaths of service to the Crown and hence excluded themselves from public life. They also tended to be at odds with the progressive and polite religious establishment that was dominant in this Age of Reason, of which Handel, with his court pension and status as a cultural icon, was so much a part. Messiah sees the coming together of the Whig composer par excellence with a Tory ideologue as librettist; and the nature of the relationship between the two remains a mystery. “I must take him as I find him,” wrote Jennens of Handel, “and make the best use I can of him.”

This Issue

February 22, 2018

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle