Norman Podhoretz’s memoir Making It was almost universally disliked when it came out in 1967. It struck a chord of hostility in the mid-twentieth-century literary world that was out of all proportion to the literary sins it may or may not have committed. The reviews were not just negative, but mean. In what may have been the meanest review of all, Wilfred Sheed, a prominent critic and novelist of the time, wrote:

In this mixture of complacency and agitation, he has written a book of no literary distinction whatever, pockmarked by clichés and little mock modesties and a woefully pedestrian tone…. Mediocrities from coast to coast will no doubt take Making It to their hearts and will use it for their own justification…. In the present condition of our society and the world, I cannot imagine a more feckless, silly book.

Even before the book was published it was an object of derision. Podhoretz’s friends urged him not to publish it, and his publisher shrank from it after reading the manuscript. Another publisher gamely took the book, but his gamble did not pay off. Word had spread throughout literary Manhattan about the god-awfulness of what Podhoretz had wrought. This and the reviews sealed the book’s fate. It was a total humiliating failure.

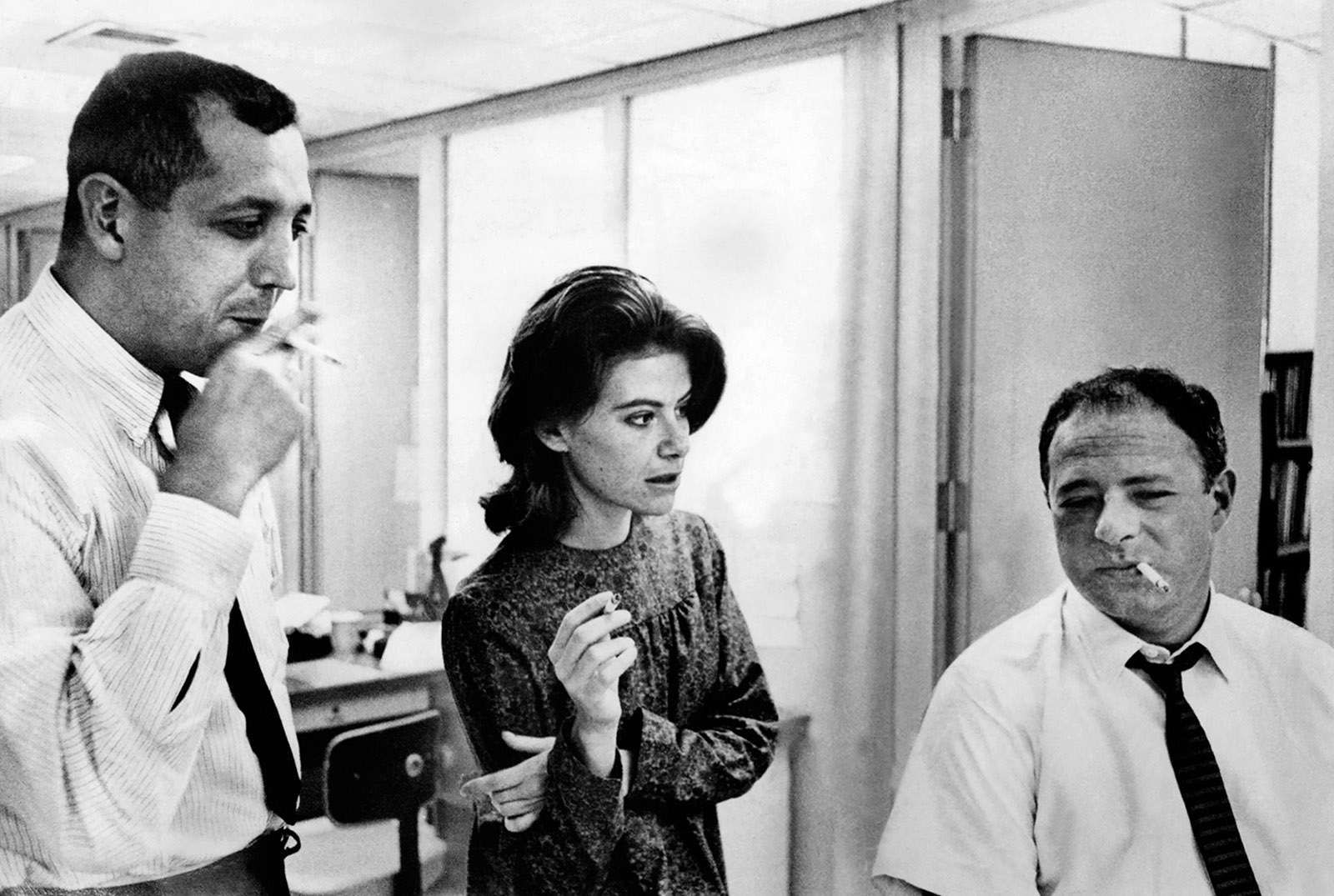

Making It was reissued last year by New York Review Books as one of its Classics, and the literary world—perhaps because it no longer exists—remained calm. Bookish people didn’t call each other up to exclaim about the scandal. Not many reviews appeared. And yet among those that did were some that in their nastiness might have been written in 1967. James Wolcott’s review in the London Review of Books was the longest and nastiest. It began with a quote from an entry in Alfred Kazin’s journal of 1963, in which Kazin wrote of a party he attended at the offices of Commentary magazine, of which Podhoretz was editor:

Struck by the oafishness of Norman Pod, drunkenly clowning in the entrance to the elevator. That lovely, blond girl (wife of the publisher of the NY Review?) looked really offended, and I couldn’t blame her.

Wolcott’s decision to begin his put-down of Making It with an image of its author as a boorish jerk, taken from a text written years before the book’s publication, may help answer the question of its original outlandish unpopularity. It illustrates a glaring problem of the autobiographical genre, namely its susceptibility to influences outside the text. At the time of the memoir’s first publication Podhoretz was a well-known if not universally well thought of figure in the New York literary establishment. He had been writing for Commentary, Partisan Review, and The New Yorker since the 1950s, when he was still in his twenties, and had become editor of Commentary in 1960 at the age of thirty. He was a kind of magnet for malice. A famous mischievous story going around was what Lauren Bacall was supposed to have said when he introduced himself to her at a cocktail party: “Fuck off, boy.”

What was Edwin Frank, the editor of New York Review Books, thinking when he decided to reprint Making It? Had he seen virtues in the book that the fog of schadenfreude had obscured in 1967? Would a new audience see them, too? In his chapter on serving in the army, Podhoretz recalls that he got along extremely well with uneducated boys from the South. “I was puzzled as to what they saw in me, and my curiosity drove me once to ask one of them why he liked me. ‘Because,’ he answered in a thick Mississippi drawl, ‘you talk so good.’”

Today’s reader of Making It will immediately see that Podhoretz writes no less good than he talks. The 1967 reviewers were simply wrong when they added bad writing to their list of offenses. Writing as lucid and vital as Podhoretz’s is not often encountered and should have been acknowledged. But the original critics were evidently too irked with the boy wonder to give him an inch. Perhaps more to the point, they could not distinguish between the book’s narrator and its author. When we read a novel narrated in the first person we do not make that mistake. We know that Humbert Humbert and Vladimir Nabokov are not the same person. In the case of autobiography, because author and narrator share a name, we are only too prone to forget that the latter is a literary construct.

The “I” of Making It is a character we have never exactly met before. The outlines of his story are familiar: a precocious, poetry-writing boy, the son of poor, Yiddish-speaking immigrants in Brownsville, Brooklyn, rises above his origins and becomes a person to be reckoned with in the larger culture. But the particulars are unusual, a little mysterious. Norman—as I will call him to distinguish him from his creator, Podhoretz—is not the conventional changeling who doesn’t belong with the Muggles he has been set down among. He is content with his lot. He is bookish and precocious, yes, but being the smartest boy in the class doesn’t ruin his life. “By the age of thirteen I had made it into the neighborhood big time, otherwise known as the Cherokees, S.A.C. [social athletic club],” he says with modest pride, and adds:

Advertisement

It had by no means been easy for me, as a mediocre athlete and a notoriously good student, to win acceptance from a gang which prided itself mainly on its masculinity and its contempt for authority, but once this had been accomplished, down the drain went any reason I might earlier have had for thinking that life could be better in any other place.

Once this had been accomplished. Norman doesn’t explain how he negotiated this improbable feat, before which getting published in Partisan Review or becoming editor of Commentary pales. He simply tells us that the gang’s uniform, a red satin jacket with white lettering stitched across the back saying “Cherokee,” was his proudest possession, and that he wore it to school every day.

He was hardly waiting for a Princess Casamassima; but one came to him anyway in the form of a snobbish teacher at his high school named Mrs. K., who made him her pet and proposed to rid him of “the disgusting ways they had taught me at home and on the streets” and thus turn him into a plausible candidate for a Harvard scholarship. Norman’s resistance to her three-year-long attempt to make him over comes to a dramatic head in a scene in which she takes him to de Pinna, a classy clothing store on Fifth Avenue, and tries to buy him a suit to wear to the Harvard interview. “Even at fifteen I understood what a fantastic act of aggression she was planning to commit against my parents and asking me to participate in,” Norman recalls.

Oh no, I said in a panic (suddenly realizing that I wanted her to buy me that suit), I can’t, my mother wouldn’t like it. “You can tell her it’s a birthday present. Or else I will tell her. If I tell her, I’m sure she won’t object.” The idea of Mrs. K. meeting my mother was more than I could bear: my mother, who spoke with a Yiddish accent and of whom, until that sickening moment, I had never known I was ashamed and so ready to betray.

Norman somehow slides away from the betrayal; the suit is not bought. He later reflects:

Looking back now at the story of my relationship with Mrs. K….what strikes me most sharply is the astonishing rudeness of this woman to whom “manners” were of such overriding concern…. Were her “good” manners derived from or conducive to a greater moral sensitivity than the “bad” manners I had learned at home and on the streets of Brownsville? I rather doubt it. The “crude” behavior of my own parents, for example, was then and is still marked by a tactfulness and a delicacy that Mrs. K. simply could not have approached.

That is very handsomely said. But the seeds of class-consciousness that Mrs. K. had planted were well sprouted by the time Norman arrived at college. What she couldn’t achieve with her obnoxious corrections, higher education achieved with its subtler admonishments. (He had received the Harvard scholarship—at the interview he wore a suit handed down from an uncle—but went to Columbia instead because it offered a more generous scholarship; the family could not afford the extra expenses of the Harvard offer.) While at Columbia Norman lived at home, traveling more than two hours by subway daily, and “I was, to all appearances, the same kid I had been before entering Columbia.” Yet

we all knew that things were not the same…. I knew that the neighborhood voices were beginning to sound coarse and raucous; I knew that our apartment was beginning to look tasteless and tawdry; I knew that the girls in quest of whom my friends and I hornily roamed the streets were beginning to strike me as too elaborately made up, too shrill in their laughter, too crude in their dress…. It was the lower-classness of Brownsville to which I was responding with irritation…. What did it matter that I genuinely loved my family and my friends, when not even love had the power to protect them from the ruthless judgments of my newly delicate, oh-so-delicate, sensibilities? What did it matter that I was still naïve enough and cowardly enough and even decent enough to pretend that my conversion to “culture” had nothing to do with class when I had already traveled so far along the road Mrs. K. had predicted I would.

“I should have made him for a dentist,” Norman’s mother murmurs to herself at a moment of special incomprehension of her boy’s new ways.

Advertisement

It was at Columbia that Norman was bitten by the crazy ambitiousness that was to become a sort of signature. For the first time he was not automatically the smartest boy in the class. In his freshman year he had to struggle just to keep up, and then he had to claw his way to being first. He attributes the excesses of his competitiveness to a realization:

My hunger for success as a student, which was great enough in itself but might yet have yielded to discipline, became absolutely uncontrollable when I began to realize that I would never make the grade as a poet…. The truth was that I could not bear the idea of not being great.

Norman won his way to the academic top by being weirdly energized by exams and by an equally uncanny ability to write papers in the styles of the professors for whom they were written. Not only A’s but A+’s poured in as a result of these aptitudes. He was not liked by a lot of his fellow students, but he didn’t care. He cared only that the professors liked him. In his final year he took a course with Lionel Trilling, who was determined not to be taken in by this famous know-it-all. But Trilling was won over by the exceptional quality of Norman’s academic performance. He, too, gave him an A+.

Trilling and his wife, Diana, became friends of Norman’s after his graduation, and Trilling was to provide an important link to the literary world outside the academy by introducing him to Elliot Cohen, the editor of Commentary. But Norman’s entrance into that world was delayed by another academic triumph. After graduation from Columbia he went to England, as the recipient of the Kellett Fellowship to Clare College at Cambridge University. Getting the coveted Kellett did not further endear Norman to his classmates, as he unrepentantly notes.

He recalls the pleasures of a room of his own, with early morning tea brought by a servant. He notes that this was the first time in his life he had the leisure to read for the sake of the work rather than to show someone how clever he was. In the English system the tutor for whom he wrote a weekly paper had no influence on the outcome of the exam he would take at the end of two years. Sucking up to him served no purpose.

[He] was the best possible antidote I could have found to the frenetic pursuit of “brilliance” to which I had become habituated at Columbia and whose imperatives constituted a more fearful tyranny, being largely internal, than any that could conceivably have been imposed upon me from the outside.

However:

There was, as usual, another side to the story. Worlds apart from the Cambridge of Clare was the Cambridge of Downing College, and if the fires within me were banked at Clare, to Downing I came, burning, burning, even more hotly than before: burning to learn, burning to impress, burning to succeed…. Downing was the college of F.R. Leavis, the greatest critic in England…the editor of the country’s most formidable critical review, the terrifying Scrutiny.

Norman wins the heart of the fanatical Leavis as he had won those of his predecessors at Columbia. He is older (twenty-one) and “no longer so unformed as to be capable of an effortless imitation of the master’s style in the papers I wrote.” But his more subtle fawning succeeds beyond his dreams: Leavis invites him to write for Scrutiny, and prints the piece.

Norman can’t help being Norman. Here as throughout the book Podhoretz writes about his hero with a finely judged mixture of affection and mockery. He knows as well as his critics that Norman’s ambitiousness verges on the insane. But such is the power of Podhoretz’s storytelling that we continue to want to follow the fortunes of his peculiar hero even as our sense of his peculiarity grows.

To complicate matters, Podhoretz has encased the story of Norman’s feverish strivings—the way chocolate encases the soft center of a bonbon—in a rather puzzling polemic about a social problem that not many readers will recognize as such, much less want to carry on about. His idea is that American culture is dominated by a doctrine of “anti-success” that keeps successful people in a perpetual state of nervous guilt over the “corruption of spirit” that underlies their power, riches, and fame. “On the one hand,” he writes, “our culture teaches us to shape our lives in accordance with the hunger for worldly things; on the other hand, it spitefully contrives to make us ashamed of the presence of those hungers in ourselves and to deprive us as far as possible of any pleasure in their satisfaction.”

This said—and how well he says it—Podhoretz goes on to describe his hero’s conquest of literary New York as anything but the angst-ridden experience we would expect it to be, given his thesis. We follow Norman’s campaign to gain acceptance into “the family”—the mostly but by no means exclusively Jewish intellectuals associated with Partisan Review—with the sort of interest we reserve for favorite sports teams. We are rooting for him even as (with Podhoretz’s good-natured permission) we are laughing at him. Commentary gave him his start, assigning him monthly book reviews. “What I wanted was to see my name in print, to be praised, and above all to attract attention.” But

it was the attention of the family I most dreamed of arousing…. There was nothing I loved better than to sit around with [Robert] Warshow or [Clement] Greenberg and listen (my wide-eyed worshipful fascination egging them on) to tales of the patriarchal past: how “Mary” had left “Philip” to marry Edmund Wilson…how “Dwight” had once organized nude swimming parties at the Cape, how “William” had really felt about “Delmore,” and how “Isaac” really felt about “Saul.” Oh to be granted the right to say “William” and “Philip” and “Dwight,” as I could already say “Bob” and “Clem” and “Nat.”

The right was granted in due course. The Partisan Review people began noticing him and soon gave him a book to review: Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March. Norman’s luck held: his dislike of the book, against the prevalent view that it was great, turned out to be the view that a lot of the family secretly held. There is a mordant account of a party at Philip Rahv’s apartment that Norman characterized as the bar mitzvah ceremony that admitted him into the family. He got very drunk. “I remember hearing my voice pronounce an incredulous, ‘You mean Alfred Kazin?’ or ‘You mean Dwight Macdonald?’ or ‘You mean Mary McCarthy?’ as Rahv and a woman who was present treated me to my first horrified experience of true family-style gossip.” After the party Norman stood out on the street violently throwing up. “And yet in the very midst of all that misery, I knew that I had never been so happy in my life.”

A few months later Norman was drafted into the army and didn’t enjoy basic training, but it was only after his release from the army that he became “more unhappy than I had ever been in my life” in a job as an editor at Commentary that had been promised to him by Elliot Cohen before he left for Fort Dix. By the time Norman came to claim the job, Commentary was no longer the place he had known when he had hung out with the editors and heard about Dwight’s nude swimming parties. Cohen had had a nervous collapse and was in a mental institution. All of its former subeditors were gone except for two men who now jointly ran the journal and did not welcome Norman into their midst. They undermined and bullied him.

Podhoretz does not name the men but combines them into a character called “The Boss.” “One of the reasons I was so miserable at Commentary during my time there under The Boss was that it had become practically the only place in the world where the sun still failed to shine on my fortunate young head,” Norman reflects. His book reviews—in Partisan Review, Commentary, and The New Yorker—had made him into what he calls a “minor literary celebrity.” At Commentary, under “The Boss,” he was made to feel like a pathetic incompetent.

Finally he couldn’t take it anymore and quit the job, but not before stopping into the offices of the American Jewish Council—the organization that owned Commentary—and telling the head of its personnel department why he was quitting. The result was a great upheaval that ended the autocratic reign of “The Boss” and allowed Norman to continue in the job as one of three equal editors. Norman asks himself: “In thus committing the prime crime of American boyhood, snitching to the authorities, did I feel guilty? A little, but mostly I felt pleased with myself for having acted so selflessly, so nobly.” Here as elsewhere Norman keeps the reader on his side by telling the story on himself. He has no illusions about the dirtiness of what he did. We helplessly admire his honesty, as the women in his childhood

marveled at my cleverness, quoting my bright sayings to one another and even back to me (“You remember what you said that time when I was here last? Let me hear you say it again.”). They called me adorable, they called me delicious, they called me a genius, and predicted a great future for me: a doctor at the very least I would be.

They probably would not have predicted his politics. Soon after writing Making It Podhoretz veered sharply right (until then he was a regular lefty like most of the rest of the family) and has grown ever more firmly committed to right-wing causes. He has written numerous books about his extreme conservative beliefs. Perhaps more than any other of the leakages from life that give autobiography its wobbly ontological status, Podhoretz’s radical post-publication politics hover over the book he wrote when he was an innocuous liberal. My attempt to seal it off from its author’s later career, and to write as if I didn’t know what I know—and what everyone who hears the name Norman Podhoretz knows—was made in the name of the New Critical ideal of textual fidelity: don’t muddy the waters with stuff surrounding the text. In the case of Making It, however, the mud clinging to the tale of the strange ambitious boy may be crucial to its discreet charm.

This Issue

March 22, 2018

Hearing Poland’s Ghosts

Fine Specimens