What may someday be remembered as the First, or the Great, or the Endless American-Afghan War is now entering its seventeenth year. Three days after the attacks in September 2001 that made the war inevitable, the CIA officer Cofer Black told a roomful of analysts at the agency’s Counterterrorist Center not to fear the outcome. “We’re the good guys,” he said, “and we’re going to win.” What happened next is the subject of Steve Coll’s intensely interesting book about the small victories and intractable delusions of America’s longest war, Directorate S: The CIA and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

But before getting into this complicated story, we ought to note what we have obtained for the something-over-a-trillion-dollars and 2,400 dead soldiers the war has cost the United States so far, leaving aside the much more numerous Afghan civilian casualties. The facts are easily found online: the number of American troops in Afghanistan reached 100,000 in mid-2010, dropped below 10,000 under Obama, and has now crept back to about 15,000. In the first year or so of the war the Taliban government was overthrown, and al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization responsible for the September 11 attacks, was chased into Pakistan. But the Taliban has risen from the ashes, is determined to regain power, and now challenges the Kabul government for control in about 45 percent of the country. A decade ago, Coll tells us, the CIA estimated that the Kabul government controlled “about half” of the country. The sunniest interpretation of the numbers is that our side is holding its own. The deeper meaning of this long struggle resists clear and simple statement.

Directorate S is the second of Coll’s long books about Afghanistan. The first, Ghost Wars, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2005, described the struggle of the Afghans to end Russian occupation and the rise of the Taliban after the Russians left. The CIA was at the center of that first book, but it plays a lesser part in the new one. That there would be a war after the September 11 attacks was never in serious question; the provocation had simply been too great. When al-Qaeda hijackers destroyed the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, more Americans were killed than died at Pearl Harbor. Compounding the offense was the Taliban government’s refusal to arrest or turn Osama bin Laden over to American authorities, or even to admit that it bore some responsibility for what he had done. The overthrow of the Taliban and seizure of Kabul came quickly, but then, with baffling abruptness, President George W. Bush and his administration turned their full attention to the invasion and occupation of Iraq, drew off troops and funds for that war, and allowed the initial victory in Afghanistan to slip away.

When the Bush government a few years later finally awoke to the Taliban’s return to the field, it was immediately confronted by the bitter truths of war against an insurgency—victory requires a troop ratio of ten to one, and if you’re not winning you’re losing. These rules emerged from painful experience during the middle decades of the twentieth century, roughly from the British war against a Malayan insurgency from 1948 until 1960 through the American campaign against the Hukbalahap insurgency in the Philippines (1946–1955), the French war to retain Algeria (1954–1962), and the war in Vietnam (1965–1975). The first two represented victory for what Cofer Black would have called the good guys. The second two were painful lessons in the prolonged effect of not winning. Coll’s new history of the current American-Afghan War, looked at from a certain slant, is not really an account of battlefield success and failure, but is rather a careful tracing of the persistent efforts by American policymakers and war planners to convince themselves every year or eighteen months that the laws of counterinsurgency are actually flexible, that dazzling new military technologies might let us finesse the ten-to-one rule, and that not losing would be okay while we look for new ways of winning.

This sad calculus of stalemate sets the dominant tone of Coll’s tale, but most of his book revolves around the central strategic problem confronting the American generals and their allies in Kabul. It comes down to a question of geography. Afghanistan shares a long mountainous border with Pakistan that the Taliban crosses into a refuge that saves them from defeat. Protest brings only excuses from the Pakistani government in Islamabad, which argues that the “tribal areas” along the border are semiautonomous, the mountainous terrain is hard to police, the Pashtun people have always traveled back and forth at will, and an attempt to seal the border would only bring the war into Pakistan itself.

Advertisement

But the Pentagon and the CIA have accumulated evidence that Islamabad is secretly protecting and supporting the Taliban as an ally in Pakistan’s long struggle with India. Managing this relationship is a separate branch within Pakistan’s principal intelligence organization, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). It is this shadowy government department—called “Directorate S” by US intelligence officials—that gives Coll’s book its title. Early in the war the president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, protested to his American allies that Pakistan was supporting their common enemy and making victory impossible. Washington resisted this analysis because it posed too many problems. Even if true, we couldn’t abandon the war, we couldn’t fight the war without bringing supplies through Pakistan, and we could hardly threaten war against Pakistan, too. But Americans in Afghanistan and Pakistan, military and CIA officers alike, all know that the Taliban’s safe refuge in the tribal areas would not have existed without the support and protection of the ISI. The fact that our ally is protecting our enemy is just one of those facts that make war such a misery.

The problem of Pakistan’s open border is never far from center stage in Coll’s history. For long periods some American officials, including President Bush, refused to take the problem seriously. But the reality of the ISI’s relationship with Islamic extremist groups, of which the Taliban is only one, was suddenly illuminated in November 2008 by large-scale terrorist attacks over four days in Mumbai, India, that killed more than 160 people. Islamabad denied any involvement in the horrors, but evidence quickly surfaced that a Pakistani-Islamic terrorist group, Lashkar-e-Taiba, was responsible. Coll tells us the CIA and the FBI documented “that several retired or active ISI officers had planned and funded the Mumbai operation.”

But why? Coll reports plausible guesses but no clear answers. The possibility that Directorate S shared the extremist goals of the terrorists could not be ruled out, but analysts thought it more likely that ISI officers were basically mending fences. “ISI may have…sought a perverse sort of credibility through the Mumbai assault,” Coll writes, “to prove to its own restive clients that it was not going soft.”

These restive clients ran the tribal areas, supported the Taliban’s war in Afghanistan, dreamed of seizing the Muslim district of Kashmir from India, and occasionally attacked official targets in Pakistan itself. Above all, the restive clients were numerous. American intelligence reported that the ISI was supporting and training as many as 100,000 armed militants in 128 different camps. Eliot Cohen, a neoconservative working for Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice at the time of the Mumbai attacks, told Coll that the episode made him reconsider the true nature of the war in Afghanistan. “I think in some ways we were actually fighting the ISI,” he said.

A month after Mumbai, President Bush, soon to leave office, traveled to Afghanistan for a final conversation with Karzai, who had been insisting for years that the big problem in the war was the ISI. Bush described the meeting in his memoirs, Decision Points, but he left out one remark jotted down by one of Karzai’s aides, who showed Coll his notes. “About ISI, [Bush] told Karzai, ‘You were right.’”

Within the American military there were two schools of thought about how to fight the war. One school, led by General David Petraeus, argued that there was no shortcut to victory. Petraeus was a serious, longtime student of counterinsurgency. He believed that victory depended less on firepower than on establishing trust with the population through direct contact. That means moving soldiers out of fortified base camps and into the countryside, where they can directly help and defend the people. At the same time an ambitious program of government reform must be enacted; that involves reducing and eventually eliminating official corruption and improving the delivery of government services, while simultaneously training the Afghan army and police to take over the burden of fighting. Petraeus had followed this approach during the “surge” in Iraq with dramatic short-term results. What the long-term results might have been we cannot say because Washington soon scaled back the effort there as too big, too open-ended, too expensive, and too unpopular at home.

The second school of thought, pressed by General John Abizaid while chief of US Central Command (2003–2007), argued that the counterinsurgency approach would take too long and would inevitably generate growing Muslim resentment. Coll summarizes Abizaid’s position thus: “The clock is ticking on the American presence.”

But Petraeus got his chance in 2010 when President Obama gave him command of American and allied forces in Afghanistan. Coll provides a rich account in a thirty-page chapter (“Lives and Limbs”) of one campaign during the single year Petraeus was given to make a difference before Obama would begin to withdraw American forces. The campaign focused on rooting out the Taliban from “the Green Zone,” an agricultural district in Helmand province near Kandahar, home territory of the Taliban leader known as Mullah Omar and a longtime center of Taliban strength.

Advertisement

A lot depended on the success of the fighting in Helmand and the rest of the country. In Washington, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s adviser Richard Holbrooke tried to express hope without really having much. In March he sent Clinton a long memo arguing that the best outcome would require an agreement with the Taliban, and the Taliban would be more willing to talk while US troop levels were going up (Obama had promised another 30,000), “not flat or declining.” But Holbrooke included a caveat: “There is an old adage: If the guerillas do not lose, they ultimately win.”

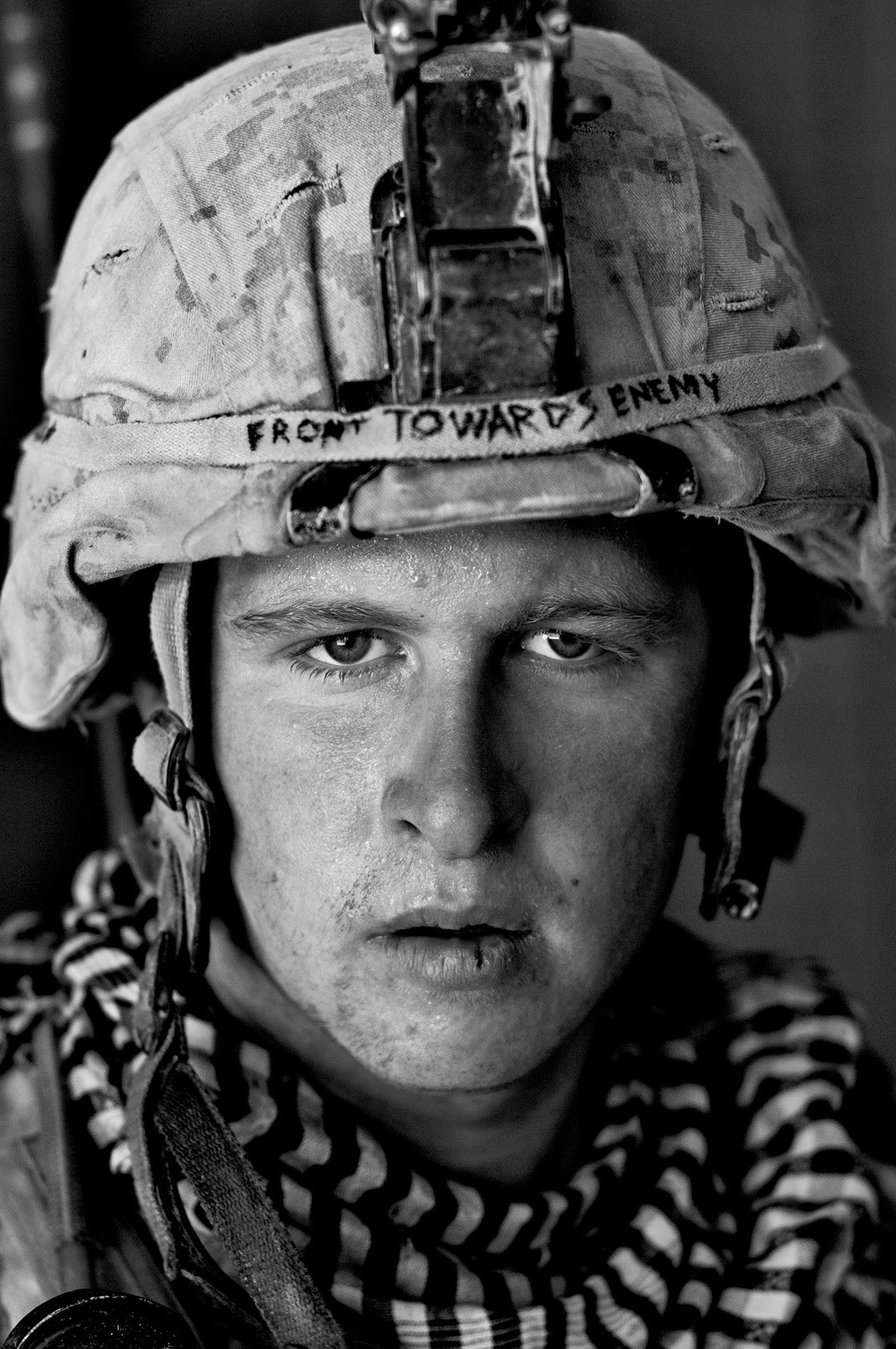

Louie Palu

US Marine Lance Corporal Damon ‘Commie’ Connell at Forward Operating Base Apache North after a patrol in Garmsir district, Helmand province, 2008; photograph by Louie Palu from War Is Only Half the Story: Ten Years of the Aftermath Project, edited by Sara Terry and Teun van der Heijden and published by Dewi Lewis. A traveling exhibition will be on view at the University of Baltimore’s Albin O. Kuhn Library and Gallery, April 2–May 26, 2018.

While Holbrooke was trying to sound hopeful in Washington, an American army colonel was studying the ground in the Green Zone to get a sense of the challenge they were facing from the local Taliban forces. On one of his visits to a base camp in the field, the colonel asked a local officer how far into the countryside his patrols were going. “About a kilometer,” the officer answered. “What happens after that?” “After that, they think we’re Russians.” It takes a moment for the meaning of that to sink in.

When the Helmand campaign began it was brutal. Coll follows one unit, the Second Combat Brigade Team of the 101st Airborne Division, for roughly a year, beginning in mid-2010. The unit fought with the usual determination to succeed, but the difficulties were immense, the time was short, the enemy was also determined, and the results were what you would expect—simultaneously impressive but hard to sustain. In just under a year the Combat Team’s casualties were 65 dead and 477 wounded. Of the wounded about 290 were never fit to return to duty, and 33 lost one, two, or three limbs.

As the Helmand campaign was winding down in the fall of 2010, Holbrooke sent Clinton another memo on the progress of the war. General Petraeus was reporting “tempered optimism,” Holbrooke said, but his own view was bleak: “Our current strategy will not succeed.” The administration intended great things but was in a hurry and didn’t want to commit “the time and resources”—that is, enough troops for as long as it took. That was General Abizaid’s rule kicking in. Besides, Holbrooke said, experience had shown there was “one constant about counter-insurgency: It does not work against an enemy with a safe sanctuary.”

Holbrooke’s conclusion: “The best that can be hoped for is a bloody stalemate.”

Failure and success are oddly mixed in Coll’s account of the Afghan war. After the quick American success in the fall of 2001, things never really looked hopeful again. But even on the quietest days of the war the Americans were not ready to say they had won, and on the bloodiest refused to say they had lost. Generals came and went, casualties rose and fell, Hamid Karzai was a more difficult ally on some days, less on others; the ISI was sometimes helpful, sometimes not. But year after year, while fighting flared and subsided, the Americans studied the war.

One early set of studies focused on the funding of the Taliban, which had prohibited the cultivation of opium poppies when it controlled Kabul. As the American war got underway the ISI was pressed to shut down funding streams from Pakistan. To deal with the shortfall the Taliban renewed poppy growing and heroin production. The Drug Enforcement Agency and the Pentagon’s office in charge of narcotics policy called for spraying poppy fields with chemical plant killers. But the generals balked, Coll writes, “because it would complicate their mission.” Karzai did not like aerial spraying either; he thought it would remind peasant farmers of Russian helicopter attacks, and he would be blamed for letting it happen again. British forces developed their own strategy for ending poppy culture: paying farmers to grow other crops. The result of all the studies and the wrangling, Coll writes, was “corruption, agricultural market distortions, and confusion.”

There were lots of other studies, too. One was conducted by Brian Williams, a professor of Islamic history at the University of Massachusetts who was recruited by the CIA in 2006 to study a sudden increase of suicide bombings in Afghanistan. He built a large case file showing that the bombers were mainly young, mainly boys, and mainly students from Islamic madrasas where they had spent years memorizing the Koran in Arabic. The Taliban paid their families a substantial sum of what might be called conscience money, sometimes as much as $10,000—“a small fortune in Waziristan,” Coll notes. When Williams had completed his work, he presented his findings at a meeting of about eighty analysts from CIA and the Pentagon. Williams said he thought the volunteers could not be explained by anything in Afghan culture, but were a byproduct—Coll calls it “spillover”—of the war in Iraq, where suicide bombing was an important part of insurgent strategy. That strongly suggested the White House was to blame for starting a second war before it had settled the first. No, no, said some in the audience; how can you know the suicides don’t have Afghan roots? The question was never settled; it just faded away. In 2007, when Williams was doing his fieldwork, about one in twenty-five Taliban bombings was a suicide bombing. By 2010 it was down to one in a hundred.

“In the closed world of secret intelligence,” Coll writes, “most analytical products wound up in locked cabinets, having had little impact. But every now and then a bestseller broke through.” The most important of these, conducted by CIA analysts late in the Bush administration, was a study of Afghanistan’s 398 administrative districts. Masses of data were collected in answer to three dozen questions. The results were recorded on color-coded District Assessment maps. “Rare is the general who does not love a map,” Coll notes. A glance revealed who was ahead, who behind. What the maps showed was that the Taliban, after six years of war, were contesting the government for control in “about half” of the country. That was about as good as it got in the American war.

The biggest studies carried out for the highest officials tended to run aground on basic questions. What were we trying to achieve? Why was nothing working enough? In the final months of the Bush administration Major General Douglas Lute, the Deputy National Security Adviser overseeing the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, conducted a long study of the fighting. Forty hours of discussion in Room 445 of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building focused on classic counterinsurgency doctrine (by then much in vogue after Petraeus’s success with the surge in Iraq), government corruption in Afghanistan, the friction among distinct military command structures (ten by Lute’s count), the need to “re-Americanize” the war (Eliot Cohen’s view), and the perennial question of why Pakistan held back. To that question the intelligence analyst Peter Lavoy had a simple answer: “Pakistan believes the Taliban will prevail in the long term.”

In mid-October 2008, Lute, Cohen, and others flew to Afghanistan for a final conversation with the men running the war in the field. Cohen later described for Coll the group’s sad discovery that members of the American team in Kabul were mostly new on the job; Cohen and Lute knew more about the progress of the war than the officers who were briefing them. After one dispiriting session Lute and Cohen retired to a men’s room where they stood side by side, thinking about what they had heard. Then at the same moment both said, “We’re fucked.”

Lute wrote a forty-page report of the group’s conclusions, which contained a list of things to do better. But Lute’s most important sentence was his first: “The United States is not losing in Afghanistan, but it is not winning either, and that is not good enough.” Coll does not linger on the meaning of this all but despairing remark, which is repeated or echoed or reworded at many moments in his history of the war. The implication was obvious: when the Americans lose patience and go home, the other side wins.

Robert Gates, the former CIA director who served as secretary of defense in both the Bush and the Obama administrations, had been around for a long time—long enough to remember the arguments over the war in Vietnam. The CIA’s District Assessment Maps said we were getting nowhere, but the generals reporting to Gates from the field in 2007 took a rosier view and said we were recovering from a near collapse of the American effort in 2006. They described the war as stabilizing. That had a familiar ring to Gates. “My sense,” he said, “is that we are not getting this right and that the situation is going sideways on us.” But Gates wasn’t about to give up, and now, nearly eleven years later, the situation is still going sideways.

Directorate S is a first-rate book, deeply researched, fairly presented, and full of the wisdom achieved only through long immersion in a subject. You can’t really pay a writer to stick to a story in this fashion; it takes too much out of a person’s life. Coll’s commitment to his subject is evident on every page, and historians will be mining the book for many decades. But its deepest insights are never put into plain words. Coll trusts his readers to understand what they are reading.

The bureaucratic entity called Directorate S was on everybody’s mind for good reason. It really exists, it has reasons of its own for protecting the Taliban, and it is the problem easiest to describe and to blame. But in Coll’s long narrative Directorate S is a half-mythical entity, something like the great white whale Moby-Dick—rarely seen, ever dangerous, an implacable force that explains all our troubles and failures, the evil thing that makes victory impossible. No study ever managed to pin it down or say what to do about it, and Coll is content to let his narrative explain itself. But the reader sees some things clearly enough. One is that we’ve been here before. Forty-plus years after our final failure in Vietnam, the United States is again fighting an endless war in a faraway place against a culture and a people we don’t understand for political reasons that make sense in Washington, but nowhere else.

Coll ends his book on page 687. The war isn’t over or even nearly over. But by this time the reader can see what lies ahead—an endless sliding sideways at some annual cost in money and lives that the American public will tolerate, because we don’t know how to win and we don’t know how to stop.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others